Religion Goes to the Movies

"Religion and Film" makes the otherwise confusing relationship between religion and film perspicuous in ways that few academic studies have .

By Robert SinnerbrinkMay 25, 2018

Religion and Film by S. Brent Plate. Columbia University Press. 224 pages.

MOVIEGOERS COULD NOT HELP but have noticed the spate of popular films dealing with religious themes and myths released in recent decades. From Godard’s Hail Mary (1985) to Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) to Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004), Darren Aronofsky’s Noah (2014), and Garth Davis’s Mary Magdalene (2018), both Hollywood and European arthouse directors have shown an interest in (typically) Christian religious narratives, continuing the long cinematic tradition of Christ narratives (“the greatest story ever told”). Add to this the ongoing fascination with the supernatural and the occult evident in recent horror films — like James Wan’s two Conjuring films (2013 and 2016) or Robert Eggers’s The Witch (2015) — and it becomes clear that the time is ripe for revisiting one of the seminal texts on the topic, S. Brent Plate’s Religion and Film: Cinema and the Re-Creation of the World (first published in the Wallflower Press Short Cuts Series, 2009). One of the premier scholars in the field, Plate deftly combined a thorough grounding in religious studies with expertise in film theory, providing an illuminating and engaging text that has enabled readers, both academic and religious, to explore the intersection between cinema and religion. Given the history of suspicion between religion and film, it is welcome to see this field not only gaining recognition but also offering new ways of thinking through the meaning and role of religion in contemporary cultural and political debates.

As Plate observes, although religion has long been a concern of the movies, the scholarly study of cinema and religion is relatively young. A glance over the history of film theory suggests that there have been roughly three waves of research focusing on the relationship between religion and film. The first wave, dating from the 1960s to the 1980s, explored theological, metaphysical, and existentialist themes in explicitly religious films, usually within the European modernist tradition (Dreyer, Bresson, Bergman, and so on) from a broadly humanist perspective. The second one, from the late 1980s and 1990s, rejected the focus on arthouse cinema and turned instead to popular cinema, spanning explicitly religious (Christological) retellings to more implicit explorations of faith or belief. Finally, the third wave, gaining popularity over the last two decades, eschews thematic, auteur- or narrative-based approaches in favor of cultural analogies between cinema and religion, focusing specifically on audience reception of films.

Plate’s book fits neatly into the third wave, taking a broadly sociological and cultural-studies approach to the exploration of religion and film, drawing on earlier approaches, but also extending these to articulate an expanded sense of the religious. Indeed, Religion and Film is not really concerned with theological motifs, the contemporary significance of the three world religions, or the rise of New Age forms of spirituality. Rather, it compares cinema and religion as ways of constructing and presenting worlds that we can temporarily inhabit, that provide new ways of experiencing and understanding our own (mundane) sense of reality. Plate focuses on the role of both religion and cinema in practices of community formation, the generation of meaning through myth and ritual, and the creation of a sacred space that contrasts with the everyday world. Religion, in this view, refers to any cultural practice capable of cultivating our sense of living in a meaningful cosmos. Such an approach enables a rich broadening of how we might understand “the religious” and helps us to appreciate what Plate argues are the striking affinities between cinema and religion.

Ways of Worldmaking

Plate’s central idea for the analogy between cinema and religion is that of world, or, more specifically, worldmaking. Cinema and religion are analogous ways of composing worlds through symbolic representation and ritualized practices. They both select and frame aspects of social reality in ways that are meaningful — providing communal forms of experience, focusing our attention, and drawing us into an alternative world in light of which our ordinary universe can appear as transfigured or transformed. Plate draws here on the work of other theorists, such as sociologist of religion Peter Berger’s Sacred Canopy (1967). For Berger, human communities create symbolic worlds to provide a sense of order and stability, staving off the threat of “cosmic chaos” through religion, which he describes as a “sacred canopy” providing shelter, meaning, and purpose. This enriched sense of world, however, also needs to be replenished or “re-created,” to use Plate’s term, in order to provide communities with a dynamic, renewable sense of place and purpose in both communal and cosmic senses.

Plate also draws on the work of American philosopher Nelson Goodman, in particular his concept of art and culture as “ways of worldmaking.” Human beings gain knowledge, according to Goodman, by constructing meaningful worlds via symbolic representations and processes of selection, synthesis, and comparison. Art is best defined, he claims, as a practice of “worldmaking” that composes “versions” of symbolic worlds using different media. In this respect, cinema can be understood as a practice of worldmaking that brings about symbolic works using audiovisual images, montage, and post-production techniques. Brent applies this idea to both cinema and religion, arguing by analogy that cinema and religion are ways of worldmaking that not only share many common features, but also mutually illuminate and influence each other.

This might seem surprising to readers, who may assume that popular Hollywood movies have little in common with the rituals of the church, mosque, or synagogue. As Plate argues, however, we gain much by recognizing how both religion and cinema construct symbolic worlds that shape our self-understanding, as well as our sense of place in both natural and cultural universes. Both involve the selection, framing, and organization of a meaningful world, and both require symbols, myths, and ritualized practice for these worlds to be rendered and recreated. Indeed, myths and rituals, for Plate, operate remarkably like films: “they utilize techniques of framing, thus including some themes, objects, and events while excluding others, and they serve to focus the participants’ attention in ways that invite humans into their worlds to become participants.” Both religion and cinema draw on materials already available to us culturally, but synthesize and recreate new worlds through symbol, ritual, and myth to create a sense of communal identity, participation, and belonging.

Audiovisual Mythmaking

Plate’s engaging inquiry commences with the important observation that cinema is our premier form of cultural mythmaking, a ubiquitous way of engaging with our treasure trove of mythic narratives. He draws attention, moreover, to the fact that myths are not simply written or spoken tales but can be multisensorial narrative experiences. Tales of origins, heroic quests, the search for identity, and binding moral, cultural, and religious narratives are richly represented in film, which uses all resources at its disposal to create an immersive sense of world within which these mythic tales unfold. Movies use primarily nonverbal means — image, sound, music, and composition (mise-en-scène) — to construct cinematic worlds that aesthetically convey this kind of mythic and symbolic meaning. Films like Star Wars (1977) and The Matrix (1999) provide convincing examples of how cinema engages in an eclectic mixing of “cosmogonies and hero myths in multiple ways, generating brand new mythologies for the twenty-first century.” It is not just their reworking of myths — the manner in which they create inhabitable worlds makes movies mythological. Star Wars’s mythic tropes of Luke Skywalker’s hero’s journey, and the Dao-like opposing energies of “the Force,” The Matrix’s references to “Zion” as a longed-for place of return from exile, with Morpheus playing the role of “pagan Lord of the Dreamworld,” all attest to the mythic richness of these films.

At the same time, Plate points to the intertwining of myth and ideology in popular cinema. The Matrix, for example, still adverts to the Hollywood myth centered on the formation of the white heterosexual couple (Neo and Trinity) coupled with a white savior myth (Neo as the One) that trumps its more alternative cultural-mythic elements. Despite its imbrication with ideology, film, like myth more generally, is an inherently eclectic cultural form, which becomes readily apparent in cinematic adaptations of religious myths. Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, for example, is a multi-mediated mythic mash-up par excellence. As Plate remarks, it draws on the following influences:

[A] millennium’s worth of Passion plays, the Stations of the Cross, the writings of nineteenth-century (anti-Semitic and possibly insane) mystic Anne Catherine Emmerich (channeled through Clemens Brentano), Renaissance and Baroque paintings (especially from Rembrandt and Caravaggio), the New Testament gospels, some brief historical scholarship, and a century’s worth of “Jesus films” (from early films on the life and passion of Jesus to Sidney Olcott’s From the Manger to the Cross [1911] to Nicholas Ray’s King of Kings [1961] and Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ [1988]).

Stylistically, the film also draws on the horror genre (the opening scenes referencing Wes Craven and John Carpenter), and its graphic depiction of violence and suffering is legendary. This only underlines the syncretic nature of cinematic mythmaking, which recreates the world via audiovisual means, engaging our senses and emotions as much as our memories and intellects.

Plate then turns to the relationship between rituals and film, exploring how “ritual’s forms and functions tell us [something important] about the ways films are created,” and examining how filmmaking can tell us something about “the aesthetic impulses behind rituals.” Here the focus is on the ways that camera movements, the use of color and light, and specific patterns of montage can create distinctive worlds through the ritualized composition of space and time. The opening sequence of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986), for example, creates a contrasting sense of world through camera movement, color, and mise-en-scène: “cosmos above, chaos below.” The revelation of this cinematic world is itself a kind of cosmogonic act, revealing this “mythic” small American town as superficially quiet, peaceful, and orderly on the surface but seething with chaotic primeval life, malevolent forces rumbling in its darker depths. Cinematography and editing help create a sense of world with distinctive features — like Blue Velvet’s dazzling primary colors, slow tracking shots of posed characters, contrasting with the disturbing sounds and murky visuals suggesting darker, ancient forces — that are carefully composed and ordered in a ritual-like manner. Cinematic composition — including framing, camera movements, light and color, sound and music — creates an inhabitable world replete with mythic and symbolic meaning.

The screen and movie theater, like the altar and place of worship, create a portal to another world; the aesthetic experience of this movie-world creates a “sacred space” in contrast to the everyday world, an experience of immersion “allowing people to interact with the alternative world, enacting the myths that help establish those world structures.” Examining films as diverse as Lasse Hallström’s Chocolat (2000), Marleen Gorris’s Antonia’s Line (1995), Dziga Vertov’s avant-garde classic Man with a Movie Camera (1929), and Ron Fricke’s environmental cine-symphony Baraka (1992), Plate elaborates the implicit parallels between the creation of an aesthetic world through cinematic composition and the creation of a sacred space through religious rituals. The composition of cinematic space, especially the symbolic connotations of vertical (transcendence) versus horizontal movement (immanence), contributes to the creation of a complex, deeply human world replete with meaning. He elaborates this claim through focused film examples, such as the futuristic dystopia of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) — with its architectural heights and slum-like depths reflecting the clash of class, technology, and alienated humanity — or the horizontal lines of everyday, small-town pilgrimage, the quietly meditative and surprisingly moral “slow” road movie that is Lynch’s The Straight Story (1999).

Religious Cinematics

In Part II of the book, Plate turns to what he calls “religious cinematics.” By this he means the manner in which film elicits an immersive experience, a bodily form of engagement through a “formalized liturgy of symbolic sensations”; one that can cause us to “shudder or sob, laugh or leap,” encouraging the body “to believe, and also to doubt,” especially in relation to images of death, pain, and suffering. Body genres such as horror provide exemplary cases of this kind of experience. Plate focuses on William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973), whose content, themes, and style are clearly germane to the exploration of religious cinematics. It is not simply narrative that explains the power of horror; rather, it is the physical-emotional reactions — our visceral, affective, and corporeal responses — that generate the powerful “non-rational” experiences that Plate links with religious responses to pain and suffering. Drawing on Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology, Plate presents a thoroughly corporeal account of our responses to horror, which are grounded in bodily perceptual belief and corporeal responsiveness toward what we are seeing on screen. It is not the plot of The Exorcist that generated the global phenomenon of fear and distress in audiences, but rather the physical-emotional responses to it, “The ways cinematic bodies were moved by the film” — not just its shocking, visceral images, but also its innovative soundtrack, which famously included “the sounds of pigs being driven to slaughter for the noise of the demons being exorcised” and “the voice of the devil coming out of Regan’s mouth.”

Plate also extends his inquiry from fictional horror to real-world engagements with death. He moves deftly from cinema’s fascination with both preserving life and overcoming death through visual representation to those rare attempts in avant-garde film and documentary film to present death, the dead body, on screen. The most notable example here is Stan Brakhage’s confronting silent documentation of medical autopsies in The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Eyes (1971). Brakhage’s attempt to symbolize death through cinematic presentation remains powerful and provocative, especially when presented as an attempt to use (literal-medical) “defacement” as part of a cinematic technique to “recreate the world” — to reveal the sacred at the heart of the Western clinical and scientific treatment of the body as corpse.

The importance of the face and the close-up in cinema is well known and offers one of the most distinctive elements explaining the emotional power of movies. Plate draws here on evolutionary biology and cognitivist theories to support his claim that facial expression is key not only to social relationships but also to exploring the boundaries between self and other. Studies of the face in visual images across religious traditions points to “the power of frontality in images and icons”; how faces look back at viewers and thereby “establish a relationship between deities and devotees” is also evident in film. The iconoclastic ban on representations of divinity also found expression in popular cinema, with the face of Christ being avoided in Hollywood film during the Production Code era — in Quo Vadis (1951) and Ben-Hur (1959), for example — appearing again only in Cecil B. DeMille’s blue-eyed Jesus (Jeffrey Hunter) in King of Kings (1961). The “face-to-face” encounter, whether in dramatic conflict or erotic exchange, is a powerful emotional element of cinematic world-creation. It shapes our sense of the world, coloring it with emotion and feeling, not only in regard to romantic love, but also spiritual or divine love (as evident, for instance, in Terrence Malick’s recent films). Emotional contagion effects (mirroring the emotional expressions of others) and nonverbal communication (expressing emotion physically in ways that resist verbal articulation) are powerful ways of binding audience and screen, opening up the possibility of an emotional and imaginative transfer between the world of the film and that of the viewer.

Cinematic Ethics

Drawing on Emmanuel Levinas, Plate also emphasizes the ethical import of the “face-to-face encounter.” It is the face that defines the cinematic ethics at the heart of religious cinematics, with its rich solicitation of the “emotional-based activity of empathy.” For Plate, cinema offers the possibility of an aesthetic encounter with the face of an Other, one that opens up a space of ethical experience: a cultural, religious, and sensuous encounter eliciting affinities and empathies that may have the power to transform us morally. Cinematic ethics means that cinema has the potential to move us toward a more ethical mode of being — from a self-regarding to an other-oriented attitude toward our world. Cognitive psychology too suggests that exposure to images of others — faces, bodies, and worlds outside our own familiar spheres — can expand our perceptual and ethical horizons, enabling us to “learn to see differently.” In this way, an ethical form of religious cinematics becomes possible, a cinematic “mindfulness” or “spiritual-sensual discipline, a ritualized form of viewing that stimulates connections between the world on-screen and on the streets.” Here the relationship between religion and cinema becomes intimate and profound as an experience of cinematic ethics that offers us “the possibility for aesthetic, ethical, and religious re-creation.”

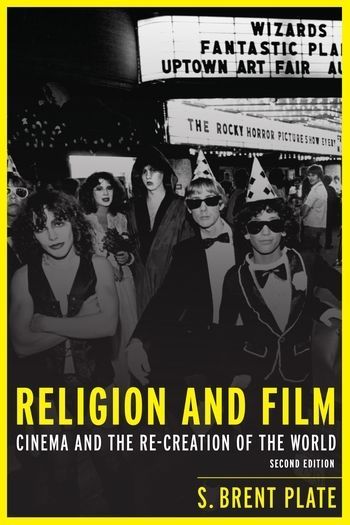

This experience of exchange is manifest in the ritualized ways that audiences interact with films beyond the movie theater and in ways that form communities of like-minded souls. Cult films, movie fandom, and the use of movie references, characters, and costumes in all manner of cultural activities — from tourism to weddings — suggest that the worldmaking expressed on screen readily translates into the re-creation of the everyday world. From Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) screenings, tourism pilgrimages to the Hobbiton Movie Set (near Matamata in New Zealand, where much of the Lord of the Rings trilogy was shot), to reenactments of epic journeys visiting sites depicted in films such as Into the Wild (2007), the parallels between the practices of ritualized mythmaking in religion and cinema become striking and compelling. As Plate remarks, the footprints of movies are left in a multitude of cultural sites, social spaces, political discourses, wilderness areas, and religious forms of consciousness throughout the world. Cinema and religion are revealed as kindred ways of worldmaking with much more in common than we might have thought.

A Religious Art?

Plate’s emphasis in this second edition of Religion and Film on audience reception also expands our sense of the manner in which we can think of cinema as akin to a “religious” form of cultural practice and shared experience. For all its secular compatibility, however, this illuminating analogy does raise some intriguing questions. Is it enough to say that any cultural practice of shared engagement with a meaningful work qualifies both the film and the engagement as “religious”? Sport would certainly qualify as religious on this account, as would forms of popular music and other kinds of collective cultural activity. As with any argument from analogy, for every parallel there are also corresponding disanalogies that should be borne in mind. To list a few, cinema need not have any relationship with theology, spirituality, or faith, whereas it is hard to think of religion without these features. Cinema is consumed as “entertainment” in industrial-commercial contexts of mass consumption — and in increasingly “personalized” platforms such as online streaming or handheld digital devices — whereas these aspects of mass entertainment seem at odds with what is conventionally understood as religious worship. The “aesthetic” aspect of religious devotion and worship, not to mention religious art and architecture, is intended to attune and transport the recipient toward an experience of the divine, whereas in cinematic experience no such transcendence is (typically) intended or even desirable (the tension between religious devotees and movie fans concerning “immoral” depictions of violence, sexuality, or blasphemy is a case in point).

On the other hand, there has been a notable upswing in the exploration of explicitly religious themes in recent popular and art cinema — surely, a worthy topic for reflection when it comes to the kinship between religion and film. Plate’s illuminating contextual, audience reception approach, although expanding our conception of both religion and cinema, does divert attention away from narrative “content.” This “content” is what many contemporary religious films have brought to the fore, particularly those exploring the nexus between religion, culture, and politics (one need only think of recent films dealing with Christian theology, religious cults, or with the question of Islamic fundamentalism and Western geopolitics).

Religion and Film is a fascinating and impressive text, both engaging and illuminating. It opens up new ways of thinking for the uninitiated as well as providing thought-provoking theses for the more expert reader. And it makes the otherwise confusing relationship between religion and film perspicuous and persuasive in ways that few academic studies have been able to achieve. It does raise the question, however, whether certain films, like other forms of religious art, could prompt or elicit religious experience: is a “conversion cinema” possible today? Or do the spheres of the aesthetic and the ethical, as Kierkegaard suggests, lead us to the threshold of the religious, without presenting it directly as such (since it is an object of faith rather than of representation). This would press the idea of cinematic worldmaking to another level of (philosophical and religious) reflection, one that might open up the possibility of talking more freely about film as a religious art.

¤

LARB Contributor

Robert Sinnerbrink is associate professor of Philosophy at Macquarie University, Sydney. He is the author of Terrence Malick: Filmmaker and Philosopher (Bloomsbury, 2019), Cinematic Ethics: Exploring Ethical Experience through Film (Routledge, 2016), New Philosophies of Film: Thinking Images (Continuum/Bloomsbury, 2011), and Understanding Hegelianism (Acumen, 2007/Routledge 2014). Photo from Macquarie University.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Reports of the Death of Religious Art Have Been Greatly Exaggerated

Are we in an era of great religious art?

Philosophes sans Frontièrs

Robert Sinnerbrink on Carlos Fraenkel's "Teaching Plato in Palestine."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!