Refusing the Death Drive Story: A Psychotherapist Reflects on HIV, COVID-19, Trauma, and Queer Attachments in a Time of Plague(s)

After decades of working with HIV-positive clients, Keiko Lane explores similarities and differences in helping her patients and communities survive COVID-19.

By Keiko LaneApril 25, 2022

(IN ALL CASE EXAMPLES from my clinical practice, clients’ identities and details are changed significantly to disguise and protect them. The issues and dilemmas raised are questions arising in my clinical practice.)

I hold my hand up to the image of her face. My fingers stumble against the phone screen.

“Sweetie, we’ve survived the plague and who knows what else. We’ll see you. Soon.”

I heard the unnamed catch in her voice. That pause before she said “soon.” She almost said “again.” None of us say it out loud.

“Soon,” I repeat. “Promise?” I ask.

“We promise,” says her wife leaning over her shoulder. She comes closer to the phone’s camera and holds her fingers to mine through the glass and the miles between us.

I’m FaceTiming with a dyke couple whom I’ve loved and considered family since we met in ACT UP 30 years ago. One of them has been HIV positive since before we met. The other has very fragile lungs. We all have gray hair now.

¤

The next day, I have a telehealth session with a psychotherapy client who is a medical first responder. They’ve looked more and more exhausted every session since the pandemic began. I worry about them. And I worry that I’m not able to take good enough care of them from a distance. Through my computer screen, I can see that they have lines embedded in their face from masks and goggles and fatigue. They rub their face between their chapped fingers during our session.

“You can’t possibly be thinking about reopening your office anytime soon.” It’s a statement, not a question.

“This is working for you? Meeting this way?” I ask.

“Yeah. I wouldn’t have thought so. But I feel contaminated. I’m more anxious when I’m around people. I can’t imagine going to your office. But I feel safe, contained here at home, being with as few people as possible outside of work, seeing you but knowing I’m not putting you or anyone else at risk right now.”

For many years, I’ve had clients who I’ve worked with via phone or video — those who live too far to commute to my office or who travel often for work and come in when they’re in town, or who struggle with chronic illness or pain and are sometimes housebound. All of those arrangements have been at the request of clients. This is the first time I am shutting the doors to my office, hoping it will be temporary, feeling like I am changing the terms of our relationship and taking something away.

I started working from home a few weeks before the mandatory shelter-in-place order. I love my office, in an old Berkeley craftsman apartment building converted into many suites of psychotherapy offices surrounding a courtyard with an ornamental plum tree that coats the ground in pink petals all spring. I’ve had my practice there for a decade. But the quirky building conversion means the suite I work in has a tiny waiting room, a narrow hallway, one bathroom, and three other offices. I can’t figure out how to keep everyone safe. I can’t figure out how to keep anyone safe.

At the end of a day of telehealth sessions with my clients, I have a video session with my therapist. Because he’s a gay man who lived through the early years of the AIDS pandemic, I know he understands the shorthand and subtext when I tell him I lost almost everyone I loved once, and I don’t think I can do it again. I tell him my deep brewing anxiety, both familiar and amplified, knowing he must have his own. Usually we’re sitting across from each other in his office. Looking out the same window when we hear the same wind, the same rain. The same sirens heading to the hospital less than a mile away. He’s in his office, sitting in the chair where he always sits, his computer screen angled so I feel almost like I’m, as usual, sitting on the couch facing him. Almost.

After my session with him, I wonder why I didn’t choose to work from my office, conducting phone and video sessions so that clients would see the familiar backdrop — the Robert Mapplethorpe print, the Japanese textiles of cranes and cherry blossoms, and the crowded bookcase. Instead, I’m at home, and though with the door closed my wife Lisa and I can’t hear each other, I know she’s working in another part of the house.

I don’t do well with separation. Separation panic predates my entrance into my family and consumes the story of my birth. I was born two months premature followed by several weeks in an incubator in the NICU. A generation earlier, my family was pulled apart and incarcerated during World War II. My mother was born in the Manzanar Internment Camp hospital, and her uncle was sent back to Okinawa and unable to return until she was in high school. His children grew up not knowing him. I feel the gut-punch of separation trauma as I watch and read reports of families separated along the Southern border of the United States. Kids in cages, parents sent away, neither knowing what has happened to the other.

Some of my clients are undocumented. When they get sick, they weigh the need for medical assessment against the possibilities of incarceration, viral exposure, and sexual abuse in detention, deportation, and permanent separation. This is familiar from the HIV pandemic: immigration status is a barrier to testing and treatment as it flags people and enters them into a tracking system designed to isolate and criminalize. The double bind is weight on their chests: stay at home and remain untested, and possibly risk spreading infection through their families; or seek care and risk incarceration and deportation. In March 2020, 75 percent of asylum seekers who were deported to Guatemala from ICE detention in the US tested positive for COVID-19.

How do we protect our communities and families now? What does it look like if care is organized around questions of distance as much as around questions of closeness? How can we enact a materially and emotionally useful and healing contact while still holding enough physical distance to make conscious decisions about risk? Who has the privileges to be able to access and choose distance? What do contact, proximity, and separation mean in the histories of all of our communities? Touch and distance are both symbolic and deeply, concretely, epidemiologically literal.

¤

A dyke friend from ACT UP who works in public health policy is entrenched in the wreck of constantly changing COVID-19 public health advisement. Her texts are an archive of the strange lexicon of the pandemic, the way ordinary language has come to symbolize incomprehensible equations of safety and risk. In the first days of the pandemic, her texts were one quick word sent between urgent meetings and said things like “bleach.” And the next day “masks.” Thirty years ago, she used to distract riot police at demonstrations, putting herself in harm’s way to capture their attention, creating the chance for some of our more vulnerable friends and comrades to pivot away from another arrest or the rise and fall of a police baton. Now, she texts early in the morning, saying “Just. Stay. In.” “We are,” I text back, “I’m worried about you.” And when I text “How are you?” she doesn’t answer.

¤

I have my first COVID-19 panic attack when I read about people dying alone, loved ones seeing each other for the last time at the entrance to emergency rooms or ambulance loading doors. Doors closing.

¤

A few months into the pandemic, I was on a webinar panel about harm reduction as community care, and how the lessons learned from HIV/AIDS might be employed in surviving COVID-19. In harm reduction, we focus less on the action or behavior causing harm than on the need the behavior is attempting to meet, and how those needs might otherwise be met. In the early plague years of HIV, before any hope of successful treatment and longevity, we were told that our desires for queer touch were toxic. We fought hard to claim the bodies of our desires. And now? What does it mean when the reduction of possible risk is the loss of contact? One of the traumas of those first plague years was the pressure to move away from the risk of embodied intimacies. Some of us were paralyzed by our fear, wanting survival more than we wanted our loved ones. Some of us responded by moving toward contact and intimacy, choosing viral risk, and the psychological risk of loss as an inevitability of attachment, a counterphobic move of insistence on embodied, social, sexual queerness as its own form of survival. Choosing a mediated viral risk over the suffering and harm of isolation. And now? Of course, COVID-19 is not transmitted just through queer contact. But we queers know something about the projection of toxicity and harm onto all bodies categorized as dangerous.

¤

During the week which would have been an annual gay men’s gathering, a client tells me he’s frustrated and depressed by lack of physical intimacy and sexual partnership. “If I had known it was going to go on this long, I would have found a fuck buddy for the duration of this.” After he says it, we both pause, thinking about it. “I know,” he says, “it isn’t even that it’s a bad idea. But it feels like too much work.”

“What part of it is too much work?”

“I’m tired. Work is nonstop. And I feel weirdly more connected to my family, even though we haven’t lived in the same time zone even in years. Now they think I’m always available on Zoom. Maybe I am. And my friends, too. I miss being in the same place with them even more than I miss having a partner. It isn’t that I want a domestic partner. I want a sex partner. That used to be easy to find. But now the amount of safety negotiations seems impossible.”

This client has been a sex educator and taught queer men of color how to navigate openly about sex and desire and safety and consent since before the cocktail in the mid-’90s. “I wouldn’t even know what to teach people now,” he says.

Neither of us knows. We’re sharing information in real time, even as I am holding space for his feelings about it.

“We know what isn’t safe. But we don’t know what is. It’s like the early days of HIV.”

He’s right, it is.

“Glory holes,” he says. “Is that the answer?”

I can’t help it, I start laughing. And we’re laughing about it together, until we both have tears in our eyes, from the sheer queer camp of it, and then from the highlighted fatigue and loss. He stops laughing, and through the screen of my computer I can see the tears in his eyes slip down his cheeks and he shakes his head.

“I mean, I love a good glory hole, and it is kind of the perfect barrier for an airborne virus. But I want intimacy, even if only for a few minutes. Sex parties, gatherings, that was more intimacy, more possible connections, not less. To have disembodiment, or less contact be the only way to fuck feels like the shame we’ve been trying to shake off.”

¤

Now there are articles in queer media outlets against cruising and hook-up culture. We fought hard to reclaim queer sex as a form of vitality and queer sociality and rebelled against the idea that it was a certain death. In psychoanalytic terms, we might think about the death drive, and the ways queerness was assumed for years in medical and psychological disciplines to be an enactment of an unconscious desire for annihilation. Now is all sociability a form of death drive?

Clients who don’t have histories of extensive trauma, or who don’t come from communities and families at risk and explicitly targeted by dominant systems of political power, white supremacy, and heteronormativity are surprised at how traumatized they feel by the way COVID-19 has changed dailiness and separated communities. I explain that in times of trauma or great stress, it’s hard for our brains to focus the way we normally would. Instead, we’re focused on survival and scanning for immediate danger. And right now, almost everything feels like a potential source of danger.

But what becomes clear to me is that they expect this to be a shock trauma. Meaning, they expect this to be something from which they recover and go back to life and embodiment and sociality as before. For those of us who live in conditions of precarity, we know that while we might still fantasize about recovering to a before, this is a developmental trauma. Meaning that it will change the course of our development. As individual bodies and as communities. And developmental traumas echo and tug at each other. That’s part of why this feels, for many of us, like AIDS — what I have for years referred to as “plague time,” until now, when we are in another plague time. And this one has both the echoes of that first one, and proximity to the political and social systems which have perpetuated it for decades.

Let me say it this way — the way we feel this moment as a traumatic rupture to social attachment is in our bodies. Is embodied. And we’re searching for new ways to be bodies together, to keep track of and experience each other’s bodies.

As I meet with my clients via video, I track their bodily expressions the way I always track their bodily expressions, but the technology creates a sort of wrinkle in time. Did they really pause before they said that, or did the connection lag? Are those tears, or a reflection? Are they holding their breath? It seems as though they are making eye contact, but there is a lens, a filter, and many miles between us.

What is the embodiment of co-regulation in a digital relational moment? Usually I’m experiencing our bodies in real time, simultaneously. I take a slow breath and settle more deeply into my chair as a client is experiencing a painful feeling and they slow their breathing and settle. It’s a form of regulatory embodiment, not unlike the ways a parent’s embodiment is mirrored by a child as the child learns affective expression, or the way, over time, we attach to and mirror the embodiment patterns of anyone with whom we have deeply intimate contact. And by deeply intimate I don’t mean sexual, or I don’t only mean sexual. I mean intentional, where we attune to and track each other. We experience our bodies in relationship to each other’s bodies. And now? How does that work with a screen between us? In that split second of delay, or the glance outside of the screen at whatever is happening in our separate spaces, we feel more separation, aware of the different frames of reference of our immediate experiences. And in that separation, the possibilities of misattunements or projections arise.

One day the computer freezes and connection drops just as a client is telling me about a fight they had with their partner. They kept talking for a moment before they realized the connection dropped and when we got the connection back, they felt unmet by me, just as they had felt unmet by their partner, even though they knew it was a failure of technology. But that’s the bind for the therapist, isn’t it? To be able to follow our clients, no matter what. The presence of technology and technological glitches makes us aware of the ways in which we interpret each other and assign meaning to somatic cues, whether we are correct or not.

Another client pauses and stares at me through the screen, wide-eyed, when I sneeze. They had just lost a colleague to COVID-19. “I’m fine.” I tell them. They don’t believe me. “Really,” I say again, “allergies. It’s spring. I promise.”

And later that evening, when I’m in session with my therapist, and he sneezes, I have the same wide-eyed worry. And before I can ask, he says, “Allergies. Really.”

¤

A friend texts that she and her partner are both sick, as are their young children. Fever, coughing, unbearable fatigue. An hour later when Lisa and I drop off bags of food on the porch, our friend comes to the door, one squirming child in her arms. Her red-rimmed and dark-circled eyes are the only part of her face I can see above her mask. Lisa and I want to go into the house, heat up dinner, rock the children, let our friends nap. But we have also agreed that for now we won’t — they’re tired but stable. So we do this: drop off dinner, groceries. Ask every day what they need. We feel both useful and useless.

How will we decide when we need to put ourselves at increased risk? And for whom?

These are the questions I’m asking, and the questions my clients are asking. We find ourselves talking through assessments of risk and community care: there are no equations of risk reduction that leave anyone feeling safe or protected. What does it mean to be permeable? This has always been an emotional question. An affective one. Now it is also an epidemiological question.

¤

A few days after the murder of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis, one of my clients was a few minutes late to our session.

“I bet you thought I got arrested last night,” she said, smiling. She looked tired.

“Well, the thought had crossed my mind,” I said. “It sounds like it crossed yours, too.”

“Yeah, I went out there.” There were the Black Lives Matter demonstrations through Oakland and San Francisco to protest yet another murder of a Black person by police. This client was a longtime organizer and had been part of many demonstrations prior to the COVID-19 lockdown. But she also lived with and took care of her grandmother, whose health was fragile.

“You know Nana has been telling me to go. And I wouldn’t because I didn’t want to risk her.”

I nodded. We’d been talking about this off and on for months, how her grandmother years ago had been a supporter of the Black Panthers in Oakland, part of an earlier generation organizing against police violence and state surveillance.

“Right, you didn’t want to risk harming her, even though she was telling you that it was all just different forms of violence, and you could stay home and be passive in the face of it or go out there and be at a different kind of risk, but not passive.”

“Yeah. Passive resistance just isn’t her thing. You can imagine the role she played back in the day.”

“So, she convinced you?”

“We compromised. A change of pod, for now. My sister came home to stay with her, since she can work from home. And I’m staying with my girlfriend, since we’re both organizing. And now we can be together. It’s also sort of a trial run of living together. And now I can also do the grocery shopping for my sister and Nana, and they can be safe.”

“You look happy about it. Are you?”

“I think so. I haven’t been away from Nana during the pandemic, so I worry about her, even though my sister is there. But I also haven’t been with my girlfriend, and I want that too. I just thought, once I came out and once my Nana accepted my queerness, which she has, and she even loves my girlfriend, then I wouldn’t have to choose.”

“And now it feels like choosing between your Nana and your girlfriend?”

“Yeah. But really it’s between my Nana and the movement. Which is even weirder.” She pauses and looks at me through the screen and it feels like we’re making eye contact, as much as we can. “Were you out there, last night, at the demonstration?”

This is a complicated question to answer. It isn’t only one question. She’s asking about my relationship to risk in this moment, what I will take a risk for. She knows I’ve been out in the streets for demonstrations before, knows I’ve been arrested. That’s how she was originally referred to me. But this is different. She’s asking how I situate myself right now. What I will put myself at risk for. A colleague argued that it is our role in queer mutual aid right now to stay as well as possible for as long as possible so we can care for other responders in the community, that we’re the only category of care provider and first responders able to stay virally sequestered and still do our job. That radical mutual aid doesn’t just look like being in the streets. And I agree with my colleague even as I’m deeply uncomfortable, and unfamiliar, with the privilege of relative safety.

“I wasn’t there last night.” I answer simply, truthfully, not crowding the space with my ambivalence, or my worry about her. We may get to those things. But for the moment, I watch as she nods, thinking about what my answer means to her.

¤

A therapist colleague starts a conversation on a clinical email list about making sure we have our professional wills intact. Which colleagues will we ask to care for our clients if we die? Who will notify our clients? This isn’t like times of private crisis, when we can take a week away from our practices, cover for each other in case of emergencies. This is all an emergency. We don’t know which one of us will be the emergency. Which ones.

Who are we prepared not to see again? That question brings a new intentionality to desires for connection where we had once been casual. We know steps toward contact will be slow, and this new caution may be permanent. The idea of restricting access to loved ones makes us want to be with them even more.

Some clients are getting restless within their sheltering. They fantasize about what they will do when it’s over, who they will see. Those of us who work with a harm reduction model of clinical practice are used to talking about full information and informed consent and clear choices and boundaries. What is an informed choice, or consent, in the absence of epidemiological certainty? How many people in our webs of human contact, from the grocery store clerks, to our family members we might need to care for or to visit, to the people we live with, to the doctors we need if we get sick with COVID-19, or anything else which requires medical care, get to consent to our choices?

Some of my clients, in their frustrations, say they know this has happened before and it ended. I know what they’re referring to, when they say it happened before and people survived and still chose pleasure.

People are writing about having lived through the AIDS epidemic as though it is over. And I know what they mean — they mean the panic of constant unpredictable loss, the panic of tracking possible exposure, the days before the cocktail, before PEP and PrEP, and before undetectable viral loads made it possible for people who are seropositive to live as normal a lifespan as though they were not seropositive.

Let me say that again: as normal a lifespan as though they were not seropositive. That means they must have access to appropriate health care and medication. And it means they don’t escape all of the issues of equity and health disparity that are now affecting mortality rates in the COVID-19 pandemic — the wildly disproportionate number of communities of color that are being gutted by the virus because systemic racism has set them up to be more vulnerable — lack of health care, food apartheid, school-to-prison-pipelines and post-incarceration discrimination limiting people’s options to low-wage, high-risk jobs they can’t not go to now because the systems that depend on their labor are not shut down, and health complexities related to stress and inequity. So I’ll say it again: people who are writing about having lived through the AIDS epidemic as though it is over are the ones who have had the health care and the economic access and maybe a little luck to have survived this far. As though the seroconversion rates aren’t now at a 50 percent chance of seropositivity in the US for Black men who have sex with men, and a 26 percent chance for transgender Latinas.

As though we are not right now and daily still living both in it and in the aftermath.

And it has stayed with us, it has stayed with me, shaping how we love, attach, desire. Obsessing over the question of whether we can save each other.

¤

It is not just the ways COVID-19 is similar to HIV, but the ways it is different that are breaking my heart. The intersection of our political, moral, and embodied politic was an insistence that quarantine and distance were not acceptable universal precautions. The ways we defied anxiety and isolation have become our ways of being, have become our identities, and are now forbidden. We rebelled against the story that our embodied queerness was a death drive by insisting on touch. Insisting on embodied expressions of love as proximity and care. We insisted on sex. We insisted on holding each other, holding our hands to each other’s faces, breathing in and out together. Feeling that connection. We asked ourselves what risks were worth taking and we took them.

Here’s what does feel the same: the way grief swirls up for those of us who have already lived through massive waves of loss. It isn’t that this is exactly the same. But it doesn’t have to be the same to be provocative. It just has to press against the same wounds. Body. Touch. Distance. Barrier. Quarantine. Separation. Death.

Remnants from the AIDS quilt are being used to make facemasks. Maybe this isn’t the grieving of the dead. Maybe this is the incorporation of our grieving into our hope for survival.

¤

The insomnia that has taken over my nights is familiar. The words that fill my head at 3:00 a.m. are some of the same keywords and questions from 30 years of grappling with the HIV pandemic:

Surveillance

Stigma

Pathogenesis

Viral count

Antibodies

Detectability

Quarantine

Criminalization

Slowly, my colleagues and I are talking about what to do. We know that people are struggling to adapt to all of the new frames in their lives, from shelter-in-place to telehealth, and we wonder what it will take for us to sit in rooms with clients again. In most professional clinical associations, there are conversations about whether we need to request frequent testing and contact tracing from our clients as conditions of reopening our offices. But for decades I’ve worked on campaigns opposing the surveillance and criminalization of HIV-positive bodies. Contact tracing has been debated in HIV public health for years. Epidemiologically it makes sense. But there is no epidemiology exempt from the current political power structures.

In other professional associations, psychotherapists want to require vaccines and frequent testing of their clients in order to resume in-person therapy. But to require expensive at-home rapid testing, or any guarantee of COVID seronegativity, will create a privileged class of clients who can come in to see us, and a virally and economically disenfranchised class of clients who can’t because their essential public labor means that they are never entirely sure they aren’t exposed to and carrying an airborne virus, even if they are vaccinated and regularly tested, especially as new variants continue to be identified.

Are we left with the option to invite people who work from home into our offices, but not teachers, nurses, grocery store staff, and sex workers? What about immunocompromised folks whose sessions might be scheduled right after those childcare center staff, ER doctors, or farm workers? Every new advance in treatment or prevention highlights the racial and economic discrepancies of access and shelter. To resume in-person psychotherapy on a rolling basis as people gain individual access to resources and viral safety feels like enacting the systems that our clients are injured by. That my clients are injured by.

There are now frequent articles about resource scarcity, which is an intentional condition of capitalism now manifesting as ethical choices for caregivers instead of as failures of responsibility of politicians and corporations and the state. In the absence of universal health care, this has always been a choice for many people; and still, those with more economic access have better chances of being treated. With shortages of oral medication and limited ventilators, doctors and nurses are being asked to choose who will be denied treatment. It isn’t just that they can’t save everyone. They can’t even try.

The field of psychotherapy isn’t exempt from moral dilemmas, and they are amplified in the discussions about sitting in rooms with clients during this pandemic. For many years, there have been those of us who question the accepted practices and lenses of our field, making explicit the necessity of understanding identities and cultural experience as part of understanding our clients’ psyches and embodiments. We interrogate with our clients the ways in which their identities locate them within political and social categories of power and precarity, and how those frame their mental and emotional well-being. And we have been willing to bring our embodied subjectivity into the room explicitly, to unmask some of the frameworks of our experiences which shape how we see, hear, and understand what they tell us, and what they omit.

And there are some things I don’t think should change: we don’t ask our clients to take care of us. We make space in our relationships with our clients so they can explore the full complexity of their desires, fears, and impulses. Including, now, their desires to expand their circles of contact, to reestablish a life and social world they recognize, their need for bodily connection. This is a strange time for psychotherapy. We are all living through this together in real time, deeply impacted by the experiences and choices of one another’s bodies in the world. If we sit in a room together, there is no way not to be affected. There is no blank slate. None of us. And yet therapy should be the place where we can bring our whole experiences away from the anxiety of impact. Or where it is symbolic and not virological. I’m pretty sure in the past I’ve gotten the flu from clients who have come in to see me when they were sick, because my office is a place where they feel safe and cared for when they are unwell. And now? Do I ask them to only come see me if they are well? And will that set them up to feel like they can’t tell the truth of their experience without jeopardizing our relationship? And what if I were the one to, unwittingly, expose them?

Some of my clients worry about me. They ask me if I’m being careful. If I’m safe. None of my clients have died of COVID-19. At least not yet. Many of my colleagues have lost clients. And more than half of my clients have lost loved ones. “Yes,” I tell them, taking a deep breath to slow myself down to make sure I’m hearing them, taking them in, and they hear me and see me slowing down to respond thoughtfully, taking their concern seriously, “I’m being safe.” It’s the same way my therapist responds when I tell him I worry about him. If only we knew what it means to be safe. As though it is only an epidemiological question, and not an emotional one as well. We’re all figuring this out in real time unfolding, together. But I understand the reassurance that my clients need when they ask, that we will get through this together. The same reassurance I need from my therapist. Even as we understand that we have no idea when we might be bodies in a shared room again, any of us.

Also, in reopening our offices, we would be bringing all of our clients into viral relationship with each other through the shared air. Other suggestions from professional organizations, in addition to increased liability insurance and liability waivers, should any of our clients get sick and feel certain that they were exposed while in our offices, waiting rooms, or bathrooms are consent to contact tracing, disclosure, and notification.

I just don’t want to. The worlds we live in always enter into psychotherapy because we bring them with us. How can I continue to structure my clinical practice, which has always been in service of vulnerable clients, so that it doesn’t contribute to their precarity?

This is not hypothetical.

What is my responsibility as a light-skinned femme-presenting person of mixed Asian ancestry? And as an HIV-seronegative person? The state tries to weaponize bodies through hierarchies of worth and checklists of respectability to earn the right to care and survival. The argument of sacrificing people to solve one crisis before the others has never worked. This is a moment when we need to insist that psychotherapy not become a weapon of anti-Blackness and anti-Indigeneity through collusion with state surveillance. Because yes, contact tracing is potentially an important part of bringing COVID-19 under containment, but what bodies are sacrificed along the way? I don’t know the answer. It might not be knowable yet. But what I do know from 20 years of practicing psychotherapy is that when we don’t know, we should slow down and make more space, not less.

Is a shift, at least for now, to solely telehealth a part of reimagining therapy as a form of queer mutual aid — which actually allows for the continuity of a queer and protected therapeutic space, instead of following the parameters suggested by current health-care systems of oppression? I grieve for my office time with clients and colleagues, and the things we give up by not sharing physical space. But grieving is a necessary part of this moment, too. Even as we make choices toward survival, we lose things.

After a long day of telehealth sessions, I check on my beloved ACT UP dyke couple again. They’re being as cautious as they can. And I miss them. Lisa and I start making calculations about how long we would have to quarantine for us to safely see them.

Am I falling into my own fantasies of COVID-19 as a shock trauma and holding the fantasy that things will return to a before? Even though none of us were safe or secure in the before. But we were, at least, together. Maybe the difference between what makes something a shock trauma or a developmental trauma is the proximity to privileges that allow one to recover to a before.

¤

One of my clients sends me a note asking to check in for a few minutes on video several days before our next scheduled psychotherapy session. She joins our Zoom session with an unusually crackly connection, and when the image stabilizes, I don’t recognize where she is. She’s a painter in her first year of an MFA program, having returned to art school, her dream, after years as a nurse. Since we’ve been meeting on Zoom, I’ve been watching her work on new paintings, canvases lining the walls behind her.

“Where are you?” I ask.

“Home.” She says. She takes a deep breath, to say more, then stops.

“Home?” I ask, and look more closely at the landscape through the window she’s sitting in front of. “Oh. You went home.” I repeat what she’s saying, trying to piece it together. She’s Indigenous, from a tribe on a reservation that has suffered devastating COVID-19 losses. She had been feeling pulled to return, to care for the elders, to be of service however she could.

“School will wait. Or it won’t. But,” I think I see tears wetting her face. “Another one passed last weekend. I couldn’t not come. If I can help. Don’t I have to?”

I’m quiet for a minute, watching her. Then I realize that she didn’t mean that rhetorically. She wants an answer from me, wants reassurance that she’s made the right decision. Even though she knows, she needs this transition to be witnessed.

I nod. “Yes,” I say to her, “you have always known what you believe about what matters most.”

She nods and says, “Anyway, I’ll see you at our appointment later this week. But I wanted you to know. In case something happens to me. In case it’s fast. I’m here. I’m glad I’m here. I’ll see you. If I can keep the internet working.”

“I’m here,” I say, “I’ll be right here.”

This client and I have talked a lot over the years about sovereignty, how the language is casually invoked in some political circles in ways that don’t match her experience of the word. That it isn’t about individual bodies and individual desires and agency, but about insisting upon gathering and protecting the resources and structural ability to support one’s community and oneself within it. Allegiance to greater survival and thriving. Protecting past and future.

¤

I check on my old friend from ACT UP, the one who works in public health and epidemiology. She’s the Indigenous cultural liaison officer in an unwieldy government organization. She’s also Indigenous. In early summer 2020, the Navajo Nation had the highest per capita COVID-19 infection rate in the United States, on top of high rates of HIV infection and food scarcity. Thirty percent of households lacked running water. She’s trying to coordinate between tribal leaders, and between tribal leaders and non-Native organizations. She meets with tribes, making space for their panic, grief, and overwhelm, mostly pushing aside her own.

¤

We want to save each other. We can’t save each other. I’ve written those lines in almost everything I’ve ever written about love and attachment during plague time. And I have always, until now, meant AIDS.

But maybe this is still plague time. Maybe this is the time of multiple viruses, but one plague. Plague, meaning the systems which attempt to break us apart from each other. To sacrifice each other.

We all want this to be quick — a shock trauma we might be able to shake off, integrate some new understanding of survival and resilience, and move forward as though this hasn’t changed the nature of how we are with each other. How we reach for each other. How we love each other. This does change the course of our development. As communities and as individuals, by the space it asks us to keep between us. We push up against the edges of that space. I do. I push back. It changes my sense of self and attachment and community responsibility and accountability to know that distance is also a form of love, a form of asserting attachment and devotion.

Because how long it took for us to reach for each other without any echo of that death drive story, now again nagging at us. How we’ve had to push away the narrative that our reach was toward damage and not care. That they aren’t sometimes the same thing. I visit with more ACT UP friends through screens. We try not to feel the screens between us as the visible echo of hospital room windows. All of us long-term survivors of one ongoing crisis are now deeply entrenched in another. This time an amplified continuation of that time. We couldn’t save each other. But we felt the beat of each other’s hearts through our fingertips against each other’s chests and cheeks. The shared breath of laying forehead to forehead, even in the crush of a tube-laden hospital bed.

We keep checking on each other, reaching through the smooth glass of screens and the crackle of phone lines. Everyone’s hearts are breaking. We don’t know how long we can do this. We keep doing this.

¤

¤

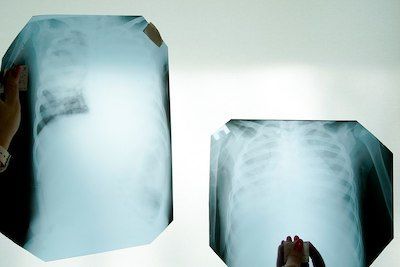

Featured image: "X-ray photograph of lungs tissue involved by COVID-19 virus. Chernivtsi, Ukraine" by Mstyslav Chernov is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

LARB Contributor

Keiko Lane is an Okinawan American poet, essayist, and psychotherapist who writes about the intersections of queer culture, oppression resistance, and liberation psychology. Her writing has appeared most recently in Queering Sexual Violence, The Feminist Porn Book, The Remedy: Queer and Trans Voices on Health and Healthcare, Between Certain Death and a Possible Future: Queer Writing on Growing Up with the AIDS Crisis, The Rumpus, and The Feminist Wire.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Cascading Crises: Alzheimer’s and COVID-19 in the Black Community

Rereading Marita Golden’s novel about Alzheimer’s in the Black community amid the COVID-19 crisis.

Behind the Numbers: Aggregated Risks in the Age of COVID

While we know more than ever about how health and disease work, experts’ inability to speak in specific terms makes it easy for them to be ignored.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!