There was a sense of an almost formal completion. But also a recognition that nothing can be learned, that to be in the presence of a death is to be in the presence of something utterly simple and utterly mysterious. In my case, the experience restored the right to use words like soul and spirit, words I had become unduly shy of.

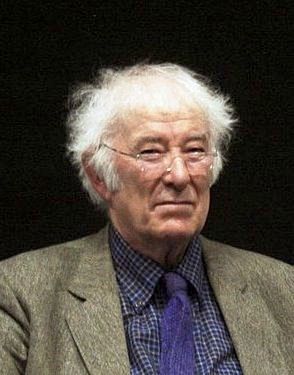

—Seamus Heaney

AN ALREADY wispy-haired man, somewhat resembling someone else’s affable and therefore adorable grandfather, standing at the front of the room, holding up his own thumb. “Like this, you see,” he explains, and I’m leaning forward, looking at his thumbnail. Everyone else is, too.

This is no small room: the auditorium at Bloomsbury Theatre, University College London, where the shortlisted poets for the 2001 T.S. Eliot Prize (awarded to a book of poems published in the U.K. that year) are reading a few days in advance of the judges’ decision. (Anne Carson would go on to win for The Beauty of the Husband.) Somehow, though, it seems as if we’re at the fireside, or around a pub table, with Seamus as he explains the genesis of “Electric Light,” the title poem of his shortlisted collection, how he was long haunted by the “smashed thumbnail / of that ancient mangled thumb,” which belonged to an elderly relative with whom the child Heaney had been abandoned overnight. It is not a cheery memory, but in introducing it Heaney’s eye seemed to sparkle — perhaps because, as the poem itself puts it, the "‘there-you-are-and-where-are-you?’ / of poetry itself” was always, for Heaney, about the possibility of connecting, across history, across geography.

¤

What is the place of the poet? What is the place of death? We, whomever we are, we who have not come to terms with our obligations, our differences, our locations, have been listening in (or not listening in) as people talk, in these Syrian days, of interventions that might masquerade as cruise missiles as surely as they might come in the form of aid packages, anything dropped from the sky as if out of nowhere. We have been listening to debates and to votes, to everyone on all sides decrying every decision. We have been counting the figures: the latest one-and-a-half-thousand, give-or-take, dead (taken, definitely, not given), somehow now more important than the last one or two hundred thousand dead.

It is in these Syrian days, when “our” options are boiled down to “go to war” or “don’t go to war” that Seamus Heaney, who insisted that poetry “should not simplify,” has died. But these have been Syrian days for a long time — two years, if not more, and Heaney just happened to pass away, after a short illness, around the time the U.K. Parliament was deciding how to be involved in Syrian lives. Perhaps these things are unconnected — or disconnected?

¤

“A guardian of the land and of the language.”

— Heaney, on the book jacket to Ted Hughes’ posthumous Collected Poems

What we say of others’ poetry perhaps reveals most about ourselves: the slippage from land to language happens easily here, which is hardly surprising for a poet whose 30-year retrospective of selected poems was called Opened Ground (1998). Heaney, after all, began his debut collection, Death of Naturalist (1966), with the poem “Digging”; there, he conflated fountain pen and shovel, both instruments for “stooping in rhythm,” for “going down and down / For the good turf.”

The poet, Heaney felt, is a delver. In an October 16th, 1973 entry in the guest book at Silkeborg Museum, the 34-year-old poet transcribed part of his poem “The Tollund Man,” later included in North (1975), one of a series of poems about humans and animals whose skeletons and bodies had been preserved in European bogs. That poem imagines Heaney going to visit Tollund Man, “To see his peat-brown head, / The mild pods of his eye-lids”; anticipating the meeting of live poet and preserved body, Heaney seems certain of the value of the encounter, certain that something will result:

Something of his sad freedom

As he rode the tumbril

Should come to me, driving,

Saying the names

Heaney seemed to relish the encounter for the encounter’s sake. His bog poems, added to over his lifetime, offer more than a meditation on human bodies and the epic span of history: they are time and again ars poetica, arguments for the ways language might shift our relationship to each other and to the lives we live on the land we fractiously cohabit. Even as he argued for an “Ireland-centered” view of Ireland’s island, he insisted that such a view was not simplistically nationalist; he fought for a way to express a connection to the land that could also rove outside, glean from other spaces. In “Terminus,” he writes of how “I grew up in between,” the poem’s title reaching back to the boundary-crossing Roman god as well as acknowledging that our modern journeys, by plane or train, end where they depart, their comings and goings all part of the same process of moving between states.

¤

Heaney was many things as well as a poet, and he will be remembered for his masterful translation of Beowulf which, like all great translations, is an intelligent, persuasive interpretation of the Old English text rather than a slavish adherence to its source material. Indeed, Heaney was articulate about the political edge to his translation:

Joseph Brodsky once said that poets' biographies are present in the sounds they make and I suppose all I am saying is that I consider Beowulf to be part of my voice-right. And yet to persuade myself that I was born into its language and that its language was born into me took a while: for somebody who grew up in the political and cultural conditions of Lord Brookeborough’s Northern Ireland, it could hardly have been otherwise.

That “otherwise” plays, cannily, two ways: Northern Ireland is both what might have distanced Heaney from his “voice-right” and the way he finds it. It would be easy to claim Beowulf for some sense of Anglo-Saxon or English identity, just as the objects from the Sutton Hoo ship-burial mound to which the poem possibly refers have been safely put on display inside the British Museum. Yet the poem is not surely Anglo-Saxon nor English, and certainly not British; it is a tale of boundary-crossing Danes and Geats, of mysterious travellers arriving among them. It is a distinctly inter-national poem, and Heaney’s claiming of it — much like Kamau Brathwaite’s claiming of T.S. Eliot in his seminal essay “Nation Language” — recognises that a poem might be available beyond its ostensible context. Beowulf, Heaney points out, is not inherently English; it is made so by critics who claim a national status for it.

Growing up in a divided, controlled Ireland, Heaney became increasingly aware of the intricate inter-operations of nationality, language, and the land. He sought a way past regionalising understandings of language, restrictive notions that a word might “belong” to a particular place and only that place. He wrote of how he wanted to locate

the place on the language map where the Usk and the uisce and the whiskey coincided [. . .] a place where the spirit might find a loophole, an escape route from what John Montague has called “the partitioned intellect,” away into some unpartitioned linguistic country, a region where one’s language would not be simply a badge of ethnicity or a matter of cultural preference or an official imposition, but an entry into further language.

That he found such a loophole in Beowulf says as much about Heaney’s willingness and ability to let language lead to “further language” as it does about the epic poem. The poet exists in language, is able to write to the degree that he or she can invest in the fluidity of language, be open to its changes.

Whether via the strata of history or the hierarchies of politics or the borders of geographic space, poetry, that art of the in-between, its line-breaks caught between fragment and sentence even in Heaney’s neatly-spooled syntax, offers a way to explore the complexities of lived existence, to resist the simple. In an interview with the Paris Review, Heaney remembered refusing to write a poem about the Maze Prison protestors in the 1979. The grounds for his refusal are instructive:

There was a big, big agitation going on in the prison. The prisoners were living in deplorable conditions. Enduring in order to maintain a principle and a dignity. I could understand the whole thing and recognized the force of the argument. And force is indeed the word because what I was being asked to do was to lend my name to something that was also an IRA propaganda campaign. I said to the [Sinn Fein] fellow that if I wrote anything I'd have to write it for myself.

Heaney here reclaims the subject of poetry from political ends, not as a solipsistic refusal of a sphere beyond the personal but in order to recognise the process a poem allows for: a working out of the complexities, a refusal of simplicity.

¤

The first serious poetry anthology I read, found browsing the shelves of Great Baddow library, was The Rattle Bag (1982), edited by Ted Hughes and Seamus Heaney — an eclectic pressing of poems across international borders, an anthology that anticipated publishing interests in translation and multiculturalism. Working in a spirit of openness — “The verse we have chosen is meant [. . .] to amplify notions of what poetry is” — the editors (their sensibilities indivisible here) write of the volume having “amassed itself like a cairn,” a thing accumulated piece by piece, by many hands, until suddenly a memorial.

The cairn holds and reveals the past, but not as a reliquary: it keeps the past animate for the living. “Had I not been awake I would have missed it,” runs the first line of a poem from Human Chain (2010), Heaney’s final book; behind that “awake” we also hear “alive.” (And in the collection’s title, again a hoped-for connection.)

¤

What is the place of the poet? And what is the place of death? How to remember the passing of a poet who had so often to write of death himself, whose tribute to his dead brother, “Mid-Term Break,” stops us with its bleak last line:

A four-foot box, a foot for every year.

then passes into silence. That blank monostich rhyming with the closing line of the last tercet — “No gaudy scars, the bumper knocked him clear” — then unable to continue past death.

For W.H. Auden, death was that time to “stop all the clocks,” a time of cessation, a time of time itself not being allowed to pass. But I think of Heaney holding up his grandfatherly thumb, a symbol of the grandmother’s departed, still-mangled thumb, connecting it to “poetry itself.” The poet does stop the action, but not to stop the clock forever: the poet wants to pause things in order to play and replay and play out their permutations, their possibilities. To pause so that we might learn to proceed differently. The poem won’t let “there-you-are” suffice; won’t dwell in simplicity.

Heaney taught us, among other things, that poetry offers a “glimpsed alternative, a revelation of potential that is denied or constantly threatened by circumstances.” It is because poetry is not only of the land, but of language, availing itself of the processes by which language forms meanings, even conflicting meanings — ambiguities, puns, ironies aplenty — that it offers us such potential.

¤

We live in a time of positions. Prime Minister David Cameron’s losing of the Syria vote has been branded a failure of tactics, a misjudgement of his “party.” The comment boards of internet websites lofty and trivial have become the modern version of Hyde Park soapboxes, spaces to launch forth opinion, heedless of how others’ ideas might shape and change ours.

Heaney would have us scoff at positions in favor of debate, of the possibility of surprise; he would want us ready to have our ideas changed, not by rhetoric but by language itself. That child Heaney, encountering the mangled thumb, was also first encountering electricity, an electricity which let him discover the wireless, and so he “roamed at will the stations of the world.” There was no stopping at these termini, for Heaney; his poetry, as his life, whether riding with Vietnam-headed soldiers across the Golden Gate Bridge or making entries in Danish museum guest books, whether living and teaching in Boston, Massachusetts or claiming — at times, having claimed for him — a role as spokesperson for a 20th century Irish sensibility (see, for example, his 1995 Nobel acceptance speech) was about delving connections, far and wide.

Heaney was less a lecturer than a conversationalist (so many anecdotes involve him meeting someone in a pub) and his poems hoped to be such. What Heaney gave us we will have to dig out alongside him. In his early poem “The Diviner,” the usually solitary role of the water-finder becomes communal, for “The bystanders would ask to have a try.” Heaney’s diviner, of course, lets them. Without him there, nothing might happen, the “forked hazel stick” simply “dead in their grasp till, nonchalantly, / He gripped expectant wrists. The hazel stirred.” It remains for us to notice the alive feeling of that stirring, to follow where it may take us. All we can be sure of is that what we find, and how we handle it, will not be simple, and must not be simplified.

¤

LARB Contributor

Lytton Smith is Lecturer in English and Creative Writing at Plymouth University. He is the author of a book of poems, The All-Purpose Magical Tent, and two translated novels from the Icelandic.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!