Reality TV’s Re-Segregation of the South

The modern South is too complex for reality programming to rely on its standard broad-brush treatment.

By Christian N. KerrMay 22, 2014

IT WILL SURPRISE no one to hear that reality TV presents a false reality to the viewer — that the characters are more caricatures than fully realized individuals, the relationships mere tinder for explosive drama. To dismiss the genre as tasteless pablum, however, is to deny what’s happening just below the semi-scripted surface. Reality TV presents the viewer with a more easily digestible world than can possibly exist in modern America, and we, as viewers, eat it up. It’s easy to gorge on reality programs — they’re the sugary sprinkles of cable, colorful and tasteless concealments of subjects too bland to swallow. This recipe is problematic no matter the locale: the reality shows of Beverly Hills reduce the place to a sun-kissed land of silicone, and those of New York City show a cutthroat city of skyscrapers. But as the genre spreads to the Deep South, the unreality of the formula proves unwittingly edifying against the region’s bitter history of racism.

The modern South is too complex for reality programming to rely on its standard broad-brush treatment. Systemic and subtle racism remains, yet the region is also the most diverse and second most integrated in the country. Reality producers elide this paradox by superimposing their simplistic formula — a pastiche of conventional Southern stereotypes perpetuates the idea of the South as an isolated bastion of outmoded values.

There’s even a de facto segregation apparent in the current spate of reality TV programs set in the Deep South. “White” shows like A&E’s Duck Dynasty and CMT’s Party Down South, respectively, show white Southerners as God-fearing rednecks or drunken hillbillies. “Black” shows like VH1’s Love & Hip Hop and Bravo’s Real Housewives of Atlanta cast black Southerners as feisty and obnoxiously wealthy entertainers, athletes, or the significant other of someone in one of these two professions. These stereotypes nourish antiquated ideas of the South as a backward place where white people are comical and mostly harmless fools, and black people are rich and successful so long as they remain petty minstrels. Despite their problematic premises (or because of them), these shows are immensely popular and profitable: the bearded businessmen of Duck Dynasty have leveraged their fame to a half-a-billion dollar enterprise, and the women from The Real Housewives of Atlanta have captured the attention of over a million viewers a week for six seasons. Clearly these cable networks have discovered an easy exploit in the perceived otherness of the South, a place the rest of America can look at and snicker. But by marking the South as somewhere separate from greater America, these shows feed the notion that racism is a uniquely Southern affliction, relieving the viewer from confronting the persistent bigotries of the real world.

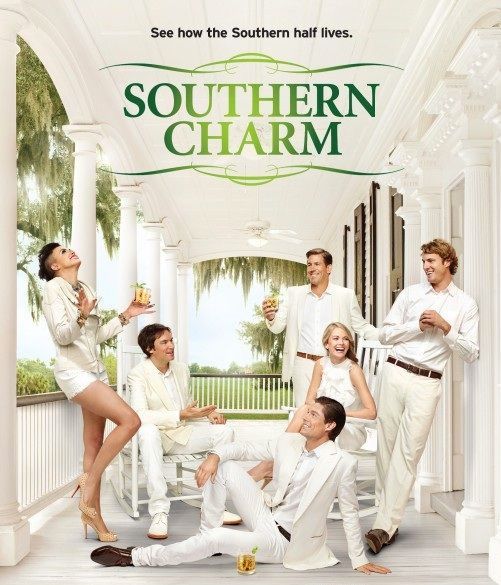

This spring, Bravo is giving viewers more of the same segregated South with the introduction of Southern Charm, and the second season of Married to Medicine. Both shows seem to flaunt some of the unflattering characteristics of their bizarro brethren: the all-white cast of Southern Charm is rich and attractive in ways the Duck Dynasty cast is wanting, and the now all-black cast of Married to Medicine (the token white character from season one is noticeably absent in season two) is supposed to contain examples of smart and professional women of color who succeed in the competitive field of medicine. But these shows still fail to confront the region’s racial tensions, choosing to portray skewed versions of the same stereotypes that have misrepresented the South for decades. At first, these shows seem like diversionary fodder (they are), but a serious look can reveal them as valuable reflections of American perceptions of race and racism.

¤

Southern Charm follows the lives of six single white Southerners in Charleston, South Carolina as they struggle to define themselves in the conservative and tight-knit society of the plantation-class South. The cast is comprised mainly of Old South aristocrats with family names and fortunes that both burden and bankroll their lives — “Because in Charleston, you’re only as good as your last garden party and one social screw-up can taint generations to come.” Or so says Bravo, which promises a show that reveals “a world of exclusivity, money and scandal that goes back generations.” Maintaining the family reputation is the ultimate priority for these characters, a problem once one remembers the heritage that’s being upheld is sullied by racism. Of course, the show focuses on social faux pas and scandalous affairs instead of the region’s racial tensions; it’s reality TV, after all. But such history is inescapable in a city as steeped in the past as Charleston, and the cameras record the vestiges of slavery in the plantation settings and ingrained family values.

This storied archetype of the Southern aristocrat is made manifest in the character of Thomas Ravenel, a former state treasurer turned buffoonish bachelor trying to rekindle his political career after serving 10 months in prison on cocaine distribution charges. His relatively short prison stay is telling of the generous sentence a strong family name and an expensive lawyer can buy a troubled white man of means. T-Rav, as he affectionately calls himself, is an emblem of white privilege that spans generations, and his father, former state Senator Arthur Ravenel Jr., is mired in racial controversy: he’s been a vocal advocate for the flying of the Confederate Flag at the South Carolina statehouse and notoriously called the NAACP the “National Association for Retarded People.” The producers of Southern Charm even give voice to Arthur Ravenel’s racist ideologies, if only to reinforce America’s favored idea that racism is relegated to the elderly rearguard of the South. Over lunch with his son, Arthur Ravenel giddily lays a five-dollar bill down as a tip, adding that he likes to get rid of that denomination because “they’s ole Lincoln” on them. T-Rav responds with a laugh: “You don’t like Lincoln?” he knowingly asks his father. The former senator flashes a sly, dentured smile to the camera, and his son chuckles at his father’s implied racism. Like T-Rav, the producers of Southern Charm shrug off the bigotry as a quaint relic of the Old South, the province of curmudgeonly white guys nearing senility.

In its premier episode, the series briefly refutes its racial casting when a character of color is tacitly introduced as the friend of Cameran Eubanks, the show’s most relatable and levelheaded cast member (who has been perfecting the role of most-believable-reality-character since appearing on MTV’s The Real World: San Diego a decade ago). Southern Charm’s producers cut to a scene of Eubanks and her friends preparing to attend one of T-Rav’s polo matches, making sure to inform the viewer that the pretty, light-skinned black girl with powdered face, unnaturally pressed hair, and impossibly blue contacts is named (of all things) Ebony. Though her name flashes across the bottom of the screen, she’s given only enough screen time to be a token of color against the whitewashed backdrop of Charleston; she hasn’t appeared on screen again since. Her cameo represents the show’s transparent denial of the South’s racist ideologies. “Look!” the producers call out, “here’s a black person hanging out with white Southerners. Segregation is over!” What Ebony’s appearance reveals, however, is a selective segregation that’s come in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement. Sure, nearly anyone can be accepted into the upper echelon of Southern society, so long as they mimic the aesthetics and beliefs of the white ruling class.

Southern Charm brims with anachronisms — families focused on ancient ancestors in an insular city built by slaves — but that very trait is the foreign charm of the South. The show reinforces this ideal as innocent entertainment, ignoring the problems festering beneath the gloss.

¤

Whereas the characters of Southern Charm are focused on the conservation of Old South values, the women of Married to Medicine seek to upend them. The show is a particularly interesting case of Southern stereotyping, as its creator and producer, Mariah Huq, is also its central cast member. Huq, the pampered wife of a Bangladeshi surgeon, originally pitched the show as a foil to the pigeonholed black entertainer/athlete mold rife in black reality TV. Centered on the small society of Atlanta’s wealthy black doctor-divas, Married to Medicine purports to show Southern black women as powerful professionals, but it unwittingly exposes the spectrum of racism, from “ghetto” to “bougie,” to which these black Southern women are confined.

The show’s characters are acutely aware of their outsider status, and try and reject it in varying degrees. Dr. Simone Whitmore and Dr. Jacqueline Walters are obsessed with etiquette and professionalism; they are the admirable examples of the show’s alleged purpose, proving that with self-awareness and restraint, even a black Southern girl can become a success in white America. Huq, producer and self-appointed “Queen Bee” of the cast, confronts these refined doctors with her friend, Quad, a Memphis girl unaware of the sterile affectation required of a black Southern woman married to a doctor. Her tempestuousness comes off as uncouth to the doctors and wives of doctors, her temper a signifier of the lower class from which she recently rose. Quad regards these women as pretentious dissemblers vainly reaching for an identity they’ve been barred from since birth. As the first season progresses, it becomes apparent that Quad’s “ghetto” outbursts are inflamed by Huq’s prodding, and the duo quickly become the show’s antagonists. Here, the producer, Mariah, is plainly promoting negative stereotypes both behind the scenes and on the screen. She becomes the embodiment of brash primitivism because she believes that is the stereotype the audience expects of a black Southern woman.

The show devolves into literal hair pulling and slapstick by the fourth episode of its first season, an incident that cast member Whitmore calls “two bitches fighting in ball gowns.” It is no coincidence that Mariah initiates the fight and proceeds to swing the first purse: it makes for great TV, and her lapse into the “ghetto” stereotype is rewarded with the highest viewership of the first season. Ratings demand drama, and Huq’s outburst resonates with the expectant audience. As a producer, she should be proud, but as a woman claiming to redefine black Southern stereotypes, she should be ashamed. Her role in the show is an insidious subversion of the progressive message of Southern black female empowerment, and her prize is a pay raise and a second season.

As the show plays out its current season with an all-black cast, it promises “sass, class, and one of the most explosive — and brutally honest — confrontations yet.” The most honest aspect of the show, however, is its inadvertently apt depiction of the constricting stereotypes within which black Southern women are confined. Married to Medicine exposes viewers to the false idea that black Southern women, despite their social and professional ascendance, can never escape the trappings of “ghetto” behavior.

¤

“How can we move past this?” This question is brought up constantly in Married to Medicine, but refers to a greater concern of modern America: how can we stomp out the smoldering embers of the South’s racist legacy? The answer isn’t clear, but it certainly starts with recognizing the agents that fan the coals. Southern reality shows — presented in stark stereotypes of black and white — reinforce the illusion of a “post-racial” America divorced from the relics of Southern racism. Producers will continue to mine the South for new angles on the same stereotypes as long as people continue to accept these caricatures as Southern truisms — a mindless acceptance that at once comforts viewers in their imagined superiority over the “backward” South while stoking racially-striated stereotypes that support this false perception. Each new Southern-centric, racially segregated reality show is another superficial concealment of the old wound of slavery and the picked scab of Jim Crow.

¤

LARB Contributor

Christian N. Kerr is a graduate student of New York University’s Cultural Reporting and Criticism program. He lives in Brooklyn by way of Alabama. Find him on Twitter: @cnkerr.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Criminal Kind: Attica Locke’s Cutting Season

Attica Locke’s latest novel is a double-edged murder mystery boasting not only Locke’s strikingly original voice, but also a timely and politically...

BDS, Racism and the New McCarthyism

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!