Race, Money, and the Pursuit of Poetry in the US Today: A Conversation with Megan Fernandes and Edgar Kunz

Natasha Hakimi Zapata interviews Megan Fernandes and Edgar Kunz about their new poetry collections.

By Natasha Hakimi ZapataJanuary 15, 2024

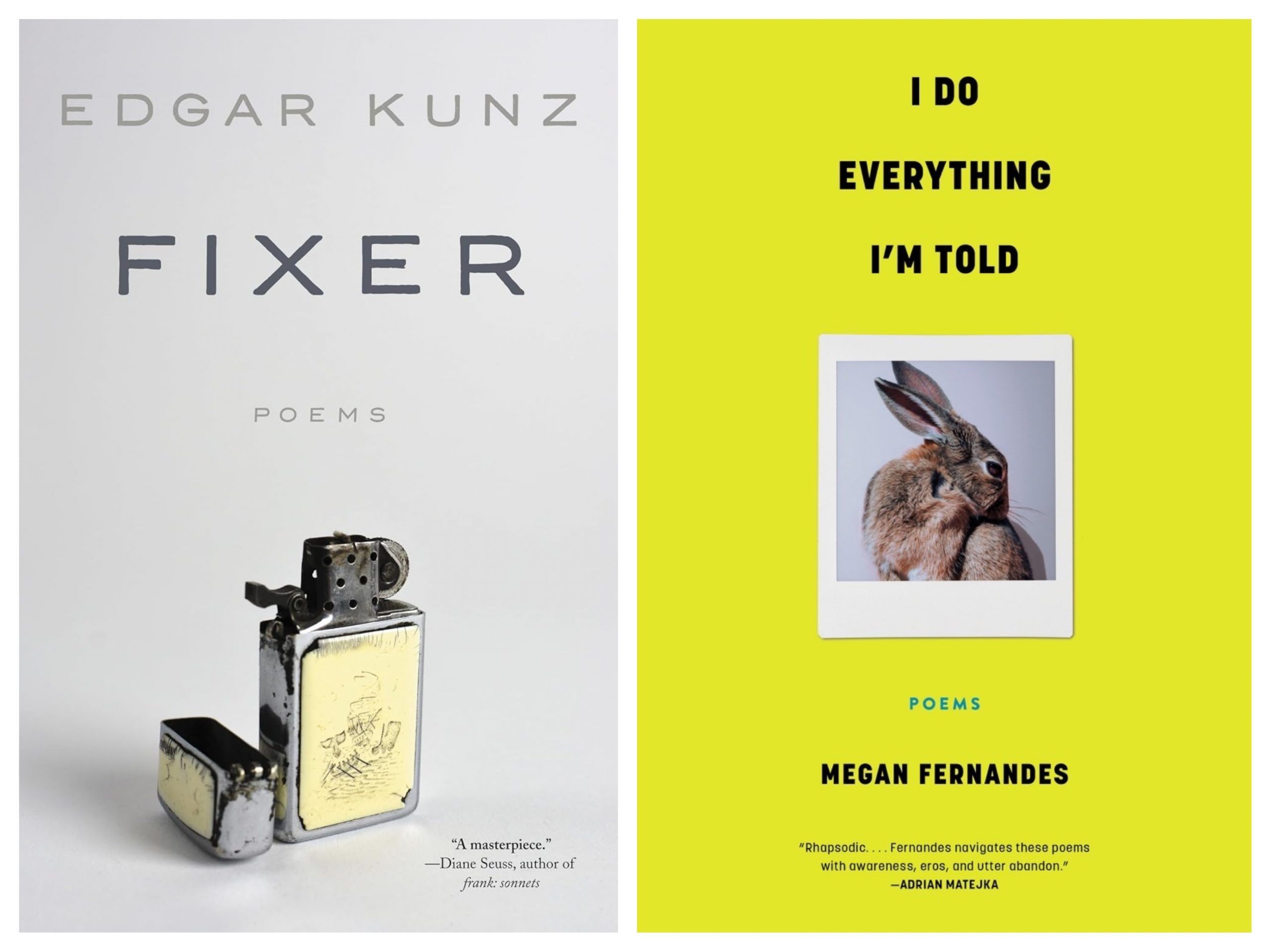

Fixer by Edgar Kunz. Harper Collins. 80 pages.

I Do Everything I’m Told by Megan Fernandes. Tin House. 104 pages.

MEGAN FERNANDES and Edgar Kunz may not write similar poems, but their poetry and their journeys intersect in more ways than one. Fernandes’s first two books grapple with the diasporic journey of the daughter of displaced Goan immigrants from Africa, expressing rage in response to the pervasive racism, queerphobia, and misogyny the books’ speakers face on a daily basis. Throughout The Kingdom and After (Tightrope, 2015) and Good Boys (Tin House, 2020), we witness a poet prodding the limits of the English language and her own poetic form, reenvisioning both ancient forms and free verse in an apparent attempt to understand whether poetry can ever truly contain the words of a queer Brown woman facing the broken promise of a postcolonial world.

Fernandes’s latest collection, I Do Everything I’m Told, made a splash last summer for its honest, often messy, and always expertly lyrical look at the boundless love that Frank O’Hara’s speaker once declared is “All I want.” Early in the book, “Letter to a Young Poet,” a prose poem, serves as an ars poetica as much as a meditation on the embodied experiences feeding the form: “It’s better to be illegible, sometimes. Then they can’t govern you. It takes time to build an ethics. Go slow.” In a later crown of sonnets, one of poetry’s most familiar forms, Fernandes proves how deftly she can craft a breathtaking love poem before she quite literally explodes it on the page, as if to say: If the form will not make space for my beloveds and me, let it burst.

In lacerating and precise verse, Kunz’s poems, peppered with food stamps, vituperative slang, and shattered working-class bodies and minds, bring poverty in the world’s wealthiest nation to life. Tap Out (Mariner, 2019), his first book, offers a poignant exploration of loving a parent who threatened the speaker’s own survival as a child, sometimes because of drunken violence, other times because he could not afford to feed or house his children. Kunz writes,

Yes, I have already begun the life-

long work of hating him, a job

that will carve me down to almost

nothing. I have already begun to catalog

every way he has failed me. Yes.

Fixer, a new collection that picks up where Tap Out left off, is a surprisingly tender, at times hopeful, depiction of a new chapter in a life marked by precarity and loss, but also by love—towards a new “sweetheart” as well as siblings whose lives have diverged from the speaker’s as his class position has shifted. Some of the strongest poems in the book—such as “Tester,” in which a speaker ends up testing the limits of language as resistance in a “gig economy”—serve as a scathing critique of late-stage capitalism and pernicious patriarchy, the real culprits behind the brutality exposed in both of his books.

From starkly different vantage points, Fernandes and Kunz deliver devastating portrayals of the everyday violences that so many Americans are subjected to yet not enough poetry takes as its subject. Their voices are as fresh as they are probing, and neither poet shies away from unveiling the nitty-gritty reality of living.

Fernandes and I have been close friends since earning our MFAs together at Boston University, but I only recently met Kunz during the London launch of their new collections. As they both wrapped up overlapping book tours across the United States and Europe in recent months, I caught up with them via video call to discuss how their lived experiences have marked their craft, whether poets should make a living from writing verse, and what the two friends have learned from one another’s “fucking hilarious” work.

¤

NATASHA HAKIMI ZAPATA: Both of you powerfully describe the challenges of trying to survive an America that in so many ways wants to erase you. How have these experiences become central to your work?

MEGAN FERNANDES: I don’t really think about survival that much when I’m writing. I always try to start from a space of doubt or unease, or something that’s not super declarative, because I think that starting from a space of questioning allows me to write poems that reflect a mind in process. Part of survival is not really having enough time to think because you have to make these quick decisions. It’s like fight or flight. But with poetry, what’s really lovely—and I tend to write somewhat longer poems—is the ability to see the mind unpack something difficult in front of the reader, and then allow the reader to make their own interpretations. I say this all the time to my students and everyone else: the poem is not a jury.

EDGAR KUNZ: This makes me think about precarity. The real problem with being poor in this country—which is a country that despises the poor—is that you are one mishap away from disaster at all times. One broken-down car, one broken bone, one missed payment. As much as we like to talk about poetry as essential—of course we do, we’re poets, we’re like, “How could we live without it? It’s an essential human activity that gets at the main dramas and drives and ecstasies and griefs of human experience”—it’s ultimately a luxury activity. It is. You need the time and the space and access to literature to make it work. A big transformation in my life has been from growing up poor to carving out a kind of middle-class life for myself that allows for that time, the leisure that allows for making art. Without having hustled my way into the position I’m in now, I don’t think I would have been able to write the books I have.

MF: Edgar and I are both hustlers. That’s something that nobody talks about because it’s not hot or romantic to constantly be worried about money. Especially since I live in a very expensive city. But I also think that, in poetry, people are deliberately opaque about their money situation, and some people love the glamorization of poverty, as if it’s romantic not to have money. Some people who really do have stable structures or security nets are playing with this kind of precarity. Precarity as an aesthetic is so gross and problematic.

Edgar, you’ve written quite powerfully about money in an essay for Lit Hub where you say, “[Money is] my great subject, my first and most lasting obsession.” You also teach poetry, and, as The New York Times put it, your “familiarity with the gig economy” became material for your work. In what ways are these jobs detrimental to your craft, and in what ways are they, perhaps unexpectedly, feeding your craft?

EK: Yeah, I’ve worked all kinds of weird jobs. I like saying yes. I’ve been a gas station hand model, a dips taste tester. I’ve mucked out stalls and spread mulch. I’ve cut glass to replace blown-out windowpanes. They never paid much—the gas station model job, which made it into the book, paid me in gift cards!—but they did feed me in other ways, including the poems I’ve been able to make out of them.

And, right, thanks for bringing up that essay. I’m proud of it. I’m not really an essayist—I write one essay for every book of poetry that I write. For this one, I wanted to talk about trying to negotiate a better rent situation for me and my sweetheart in the Bay Area, which is almost impossible to live in. And that developed into this essay about hustle culture and about money and poetry, and about the fellowship circuit and the book prize circuit and all of the material facts of trying to be an American poet in the 21st century.

What I’m proudest of is that I name numbers. I say, “This is how much the fellowship paid me. This is how much my rent was. This is how much my family made in a year growing up and so on.” In not talking about it, who is served? Not my peers, not me, not anyone at the bottom, hoping to be chosen, hoping to be plucked out of the pile. It felt important to do that.

MF: And let’s also talk about unpaid labor. Let’s talk about all the emotional and affective labor women have to do for literally everyone. Not just our partners and parents and friends and students and colleagues, but anybody we’ve ever taught in a workshop or the random people we meet at a reading, people I don’t even know that well. Women and femmes are constantly doing a lot of analytical labor, a lot of emotional labor for the people in our lives, which is not compensatory because it exists outside of capital. There’s a reason for that, because capital is designed not to pay women and femmes for that labor. I always tell young women and young femmes: be as selfish as possible. For as long as possible. It’s not selfish. It’s just actually trying to make time for your art.

What you’re saying is not a new thing, right? It’s from Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, this idea of protecting space in a life for writing. The New York Times recently had a profile of the current poet laureate titled “Ada Limón Makes Poems for a Living,” in which she recognizes she’s a “unicorn” who doesn’t teach or have a “day job” or independent wealth. Should all poets be able to make a living from their writing?

MF: Listen, I think poetry has had this relationship to leisure and the leisure class or patronage for too long. And not to be this immigrant, but jobs can be good for people. Sometimes my friends are so self-indulgent with their emotional lives, which poets already are because we are structured to pay close attention to our inner life. It’s beautiful. But also, sometimes you need a place to go at 9:00 a.m. You need something that requires you to participate in a sociality that is a little unromantic. That doesn’t always have to do with being expressive. If you’re expressing all the time, something gets a bit diluted. I don’t really know many poets who make a living from their writing, and those that do usually have family money or are married to a lawyer or something.

Also, part of what’s great about poetry is its particular relationship to time. There’s a reason we’re not writing long-form. We write things in spurts. Poetry is probably one of the only genres where brevity is a formal constraint we can work with. Writing “in between” tasks also has its pleasures.

EK: There are two things in tension in my head right now. One is that working for money is often a predatory enterprise, where the worker is being taken advantage of and abused, to greater or lesser extents. But also, there’s real dignity and meaning in work. And I don’t think we talk about that enough, especially as progressives in the arts. It’s good to be busy. It’s good to be engaged in making, building, teaching, serving. A lot of the dialogue around this is classist and elitist. It bothers me.

Can you describe what you see as your roles as poets in a country and a world that can sometimes seem so hostile to poetry?

EK: It’s hard for me to tell what the broader cultural stance is toward poetry. On the one hand, it’s treated as a circus sideshow. Everyone’s kind of like, “Oh, those weirdos writing their little things that nobody really reads.” And then, on the other hand, it’s becoming commercialized. In recent years, because of the popularity of spoken-word poetry and the “Button Poetry” YouTube channel, if my students have encountered poetry before they enter my classroom, that’s where they’ve encountered it. And that’s been great for poetry.

There’s been a spike in book sales for poets, more places trying to bring poets to read and speak. It means more people are engaging with reading poetry, and it means poets maybe are making some money off their poems. But I also worry that it associates us with the market. It turns what we do into commerce. One of the beautiful things for me about poetry is that it’s barely involved with selling. Most of these presses are losing money on the poetry they sell. I think that’s beautiful. When poetry gets associated with an active economy around making and selling books, then we have to contend with all of the baggage that comes with that, including the pressure to be more legible, to borrow a term from conversations Meg and I have had. You’re forced into a kind of mass legibility that can be really deadening for the art.

MF: I just think the role of the poet is to believe in people and to insist on humanity and to think that the world can be half redeemable.

You remind me of how, for the painter Alice Neel, it was a really radical move to paint people, especially people from cultural and class backgrounds that rarely appeared in the visual arts, at a time when everyone was painting abstracts. I think about all the poetry that focuses solely on nature, or poetry that talks about money or real life in an abstract way, whereas both of you bring us into the nitty-gritty of life and of people.

MF: We both love people. We love strangers. Every damn cab driver we met on our book tour together became instant homies with Edgar. Ease, man. And I think that’s why Edgar is also so good at writing dialogue. But in terms of people, maybe what you’re saying is something like, when you’ve had your identity or position reified in the world for all of the canon, of course you’re gonna abstract. It’s been done. You’ve been done before. Literally, your form has been done before, which is why Alice Neel was great. There’s also this great essay by Ken Chen called “Authenticity Obsession, or Conceptualism as Minstrel Show,” where he says something like, lyric poetry is said to be over by all these experimental language poets, but that’s only because they’ve always had the “I.” What happens when you don’t have the “I”? You gotta write poems about your emotional reality—which, by the way, is a reality that has been untold.

This question is for Megan. In The Kingdom and After, one of the central concerns is about the histories we carry as displaced people and how to find space for them in our bodies, in our lives. In Good Boys, the humiliations of everyday racism often fuel furious verses. But by the time of I Do Everything I’m Told, these concerns themselves seem to have been displaced by a boundless love that laughs in the face of imaginary borders. Are love poems your antidote to the aches and pains of the diasporic experience?

MF: Everyone is to be loved and everyone is to be blamed. The “targets” of the arrows are everyone in that book. Much more democratic. The beloveds are also everyone. For me, that first book was a little bit of an experiment. It’s kind of the weirdest book in a way. It was about the positionality of the speaker as this 25-year-old, young, bright-eyed femme. There’s something kind of girlish about the speaker.

Then, Good Boys is more ragey and interested in an aesthetics of improvisation and self-destruction. In the latest book, the speaker almost doesn’t matter. It’s a more observational book. They’re watching: What’s around me? What’s the city around me? Who’s around me? What am I hearing? There’s something decentralizing about the speaker, not as an antidote but maybe as a way to push back against solipsism and insularity and all these things we can accuse our speakers of. The speaker doesn’t want to have the same emotional parameters as the speakers in the other books.

Speaking of love, Edgar, in Tap Out you show us the unexpected shapes love can take in the face of often dehumanizing poverty. In Fixer, a book described as being about love and late capitalism, the speaker is often finding space for tenderness in a life marked by steep financial cliffs. What can love poems offer amid such instability?

EK: I think, in a real way, close attention is love. That’s what love is: carving out time to really look, to really notice, to try to know something outside of an extractive economy. Writing love poems feels like a way of pushing back against the pressures of living under a system that demands your labor and time and gives you little in return. But I also think I just fucking wanted to write some love poems. I wanted to challenge myself to do it. In my first book, you could argue that some of those poems are love poems just in the really close attention paid mostly to my dad, who features prominently. I imagined myself into spaces where he was that I didn’t have access to, and I think you could argue that that is a kind of love. But I wanted to write about romantic love finally, for the first time.

The poem that I think the whole book is working toward is called “Night Heron.” It’s about my sweetheart and how the early stages of our relationship coincided with my dad dying. Her dad also died at almost the same age of the same accumulation of illnesses, depression and addiction and so on. That was my way in. I got to talk about starting out in a relationship and then my dad died and then I had to go home and do all of the labor of cleaning his apartment and trying to figure out who he was going to be to me going forward. And that weirdly had everything to do with what shape the romantic love that I shared with my sweetheart was going to take.

To insist on love feels radical. And it felt like a necessary next step for me as an artist.

As this is the Los Angeles Review of Books, let’s talk a bit about California. Edgar, you were a Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford and you’ve written about how hard it was to live in the Bay Area. What mark has California left on your craft?

EK: The Bay Area is hard to live in, but it was also supremely easy to live in. There was an ease to my day-to-day life that I had never experienced anywhere else. It was hard to make rent. It was hard to afford food. But to go outside and to be on Lake Merritt, watching the pelicans fly by, every day was perfect. I didn’t own a car. I just rode my bike and rode the train around. I was blissed out. At the same time, I was on the verge of bankruptcy in a very real sense. It was also one of the first times when I felt myself fitting into a writing scene. I had a group of friends that were all writers, and we were all invested in each other and in each other’s work. I really had never had that before. In that sense, it was important for me too.

But I can never write about a place until I leave it. There’s a certain amount of distance I need to allow to accumulate between me and a place. While I was in California, all I tried to do was write about California, and all the poems sucked. And then I moved away and suddenly all I can write about is California, and the poems are pretty good. It’s like the distance allows the lens to focus, or allows you to forget enough.

What about you, Megan? You did your PhD at UC Santa Barbara, and California actually comes up in every one of your books.

MF: I lived in California for a long time, but I really just fuck with the East Coast. I’ve spent so much time in different parts of California. I do stan Big Sur, which I think is the most beautiful place I’ve ever been to in my life and there’s something supernatural there, but the thing about Big Sur is there’s something also kind of sinister about the beauty. And in a lot of places in California, I think there’s this glossiness of beauty, and I just don’t like beauty by itself. I don’t find it trustworthy. There’s too much that California invests in its own iconography of beauty. That is uninteresting to me. I find it boring. And in reality, so many parts of the state (especially inland) are actually not like that at all. They are hurting. There is a countercultural history, a broken utopian dream that really lingers there. But it’s almost like those parts have been cut out of the narrative.

Why is L.A. “ruining some of you,” as you acerbically declare in your Rilkean “Letter to a Young Poet”?

MF: I’m just not on board for the brand of L.A., and I think it’s ruining some of you who are too comfortable there.

With new books out, you’ve been doing readings together in recent months during your book tours. I know, Edgar, you have a moving poem called “Therapy” that mentions Megan directly. What have you learned from each other and each other’s work?

EK: I think we’re both fucking hilarious. It’s really hard to write a funny poem or a devastating poem that includes moments of humor, and we both have found a way. I honestly learned a lot about how to do that from Meg’s work. We don’t get enough credit for being funny, Meg.

MF: We are. And also humble! But seriously, one thing I’ve learned from Edgar are these kinds of small, scaled-down interactions in his work, where not a lot has to be said for so much to be conveyed. The first poem of the “Fixer” series is so spare, and from poems like that one, I’ve learned something about how to be spare but also convey a lot without being didactic. That and dialogue, because you’re also really good at dialogue.

EK: Another thing I love about Meg’s poems is their omnivorousness, their expansiveness. How obscenity and fury and love and Paris are all in the same poem. You can never predict where a poem is going to go. But you can count on its intelligence.

¤

Megan Fernandes is the author of Good Boys (2020) and a finalist for the Kundiman Poetry Prize and the Paterson Poetry Prize. Her poems have been published in The New Yorker, Kenyon Review, The American Poetry Review, Ploughshares, The Common, and the Academy of American Poets, among others. An associate professor of English and the writer-in-residence at Lafayette College, Fernandes lives in New York City.

Edgar Kunz is the author of Tap Out (2019), a New York Times “New & Noteworthy” pick. His writing has been supported by fellowships and awards from the National Endowment for the Arts, MacDowell, Vanderbilt University, and Stanford University, where he was a Wallace Stegner Fellow. His poems appear widely, including in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and Poetry. He lives in Baltimore and teaches at Goucher College.

¤

Transcription by Antonia von Litschgi.

LARB Contributor

Natasha Hakimi Zapata is an award-winning journalist and university lecturer whose nonfiction book Another World Is Possible is forthcoming with the New Press in 2025. Her work has appeared in The Nation, Los Angeles Review of Books, In These Times, Truthdig, Los Angeles Magazine, and elsewhere, and has received several Southern California Journalism and National Arts & Entertainment Journalism awards, among other honors.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Unplotting Trauma: On Elisa Gonzalez’s “Grand Tour”

C. Francis Fisher reviews Elisa Gonzalez’s “Grand Tour.”

Recovering a World: On Franny Choi’s “The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On”

Sharon Lin reviews Franny Choi’s “The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!