Pseudo-Events in the 21st Century

Daniel Boorstin’s 1962 book “The Image” brilliantly prefigured our world of digital media and news as entertainment.

By Chris YogerstSeptember 2, 2021

IT’S THAT TIME AGAIN when Jon Stewart’s 2004 takedown of Tucker Carlson on CNN’s Crossfire goes viral. Stewart knew that many journalists in the burgeoning 24/7 news cycle were harming us more than informing us. “You’re doing theater,” Stewart argued, before highlighting Carlson’s silly bowtie. In fact, Stewart may be the reason the Swanson’s frozen food heir ditched the accessory, if not why CNN cancelled the program. Stewart was on to something: news was, and still is, being conflated with entertainment.

Back in 1985, in his prescient work of media criticism Amusing Ourselves to Death, Neil Postman bluntly observed that there’s “no business but show business,” bemoaning the ongoing descent of news into mere entertainment. Douglas Rushkoff’s book Present Shock: When Everything Happens Now (2013) updated the argument for the digital era, warning about the dangers of being “always on.” Long prior to Postman and Rushkoff, however, another commentator had decried the whole dumpster fire of the media and celebrity landscape that was emerging in the postwar era. Indeed, Daniel J. Boorstin’s 1962 book, The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America, may be more relevant now than when it was first published, a prophetic guide to our world of 24-hour news that foresaw the decay of media literacy plaguing us all today.

During the pandemic, we’ve spent so much time on our computers and smartphones that we yearn for more in-person interactions. Yet we also have a perfect opportunity to reflect on the ripple effects of a life lived in the digital domain. Stress and depression were drastically amplified during a year of endless Zoom meetings and Facebook feeds. The pandemic has magnified our sense of the unhealthy division between reality and online worlds, the blurred line between social media and social reality. As a great episode of South Park once queried, who has more power, the user or their profile? The important distinction, of course, is that one reality, the digital, is entirely constructed: there is nothing organic about it. Yet news is now reported based on what is trending online — i.e., who tweeted what lately. How can we create a new wave of media literacy, and achieve more harmony and a sense of value in our lives, in such a discombobulating environment?

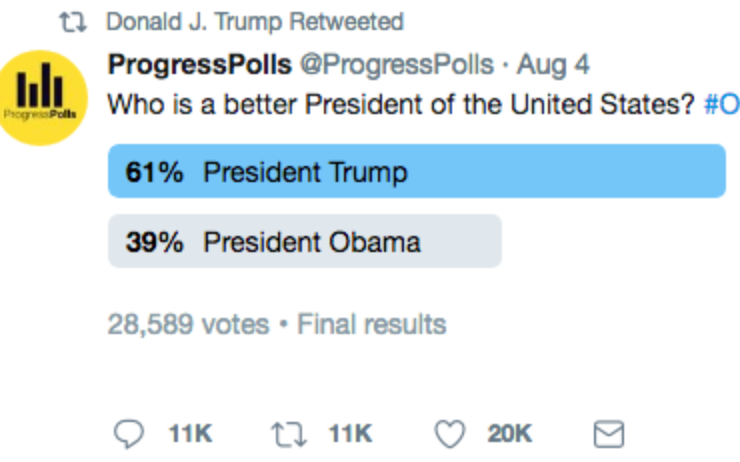

The answers can be found in The Image. Watching the rise of television, new forms of celebrity, and a culture of homogenization in the 1950s, Boorstin warned of the dangers of “self-deception” and “national self-hypnosis.” Part of the problem was a rapid rise in the supply of — and demand for — news that began to close gaps in the news cycle. These gaps were not being filled with essential stories, but with what Boorstin called “pseudo-events” created for the sake of being reported. Boorstin worried that such pseudo-events would take over as presumably important happenings. “We are haunted,” he argued, “not by reality, but by those images we have put in place of reality.” In the 21st century, it is easy to see that he was right simply by taking a few minutes to doomscroll your Twitter feed.

But how can we differentiate stories that are truly newsworthy from all the noise? In order to help us sift through the synthetic and identify valuable information, Boorstin defines pseudo-events as having four components. First, a pseudo-event “is not spontaneous, but comes about because someone has planned, planted, or incited it.” Boorstin saw film and music awards shows as a perfect example: the nominated products, which have already been released, now come with their own marketing campaigns. Awards shows are constructed solely for the purpose of being reported on, analyzed by journalists and fans, thus creating buzz about the industry that will lead to more product sales.

Boorstin’s second point is that pseudo-events are “planted primarily (not always exclusively) for the immediate purpose of being reported or reproduced.” Universities often like to puff their prestige as “distinguished institutions” through campaigns, slogans, and public events, in the process focusing on perceived standing over actual accomplishments. This system was a major factor in the recent college admissions scandals, with perceived prestige leading ignorant and wealthy parents to believe that their children would only be on a path of success if they went to the “right” schools. Such are the ripple effects of pseudo-events.

Third, a pseudo-event’s “relation to the underlying reality of the situation is ambiguous.” In other words, the purpose of the event is either unclear or simply deceptive. Finally, and most damningly, a pseudo-event is usually “intended to be a self-fulfilling prophecy.” Those who create the pseudo-event are the only ones who really gain from it. For example, calling a book a “best seller” automatically makes it worthy of reporting regardless of its actual sales numbers; readers are pressured to read the book or run the risk of missing out. (Boorstin noted that publishers rarely shared sales statistics, so one could not test the validity of their promotional claims.)

To apply all this to the digital era, consider anything done online as a means to acquire likes and followers. Such motivation is not limited to desperate individuals looking to become YouTube or Instagram or TikTok sensations. News organizations also develop their feeds to get attention, drive traffic to their website, and grow their ratings. Boorstin argued that “we suffer from extravagant expectations” because we need something groundbreaking and new every day. In the 1950s, Boorstin witnessed a growing desire to see something monumental reported on the evening TV news broadcasts and again the next morning in the paper. Today, this hankering for a steady stream of eye-catching “content” has produced an endless supply of wannabe celebrities who use social media to shill for companies by making unboxing videos. These videos are created for the sole purpose of getting attention, with a side-effect of product placement: pseudo-events for pseudo-celebrities.

HBO’s new documentary Fake Famous highlights the ease with which someone can now create celebrity out of thin air. Social media influencers can basically purchase their followers, meticulously manufacture glitz and glamour, and see their profiles begin to grow “organically.” In the show, two of the constructed celebrities get cold feet, but one fully embraces the lie her influencer status is built on. Boorstin saw this type of blind acceptance as an unrealistic view of “our power to shape the world […] [o]f our ability to create events when there are none, to make heroes when they don’t exist, to be somewhere else when we haven’t left home […] [t]o fabricate national purposes when we lack them, to pursue these purposes after we have fabricated them.” Fame on social media imitates prefabricated norms of celebrity performance; influencers appear important but remain easily replaceable and reproducible.

Boorstin was right about the changing status of fame and celebrity. “Wherever it reaches,” he observes, “it confuses traditional forms of achievement. It focuses on the personality rather than on the work. It puts a premium on well-knownness for its own sake.” Examples he cites include authors like Hemingway, Salinger, and Mailer, who all eventually became known more for their personalities than for their work (in his opinion). This “personality as celebrity” template would take over in the coming decades and now rules the 21st century. Today, one does not need talent to become a celebrity: you can skip the hassle of having to be good at anything and move right to “influencer” status if you can conjure up enough clicks and likes. The problem, of course, is that such “influence” is not determined by valuable insights but is instead driven only by traffic. Twitter’s definition of an influential individual — i.e., someone deserving of a “verified” account — is a user who has a “follower count […] in the top .05% of active accounts located in the same geographic region.” The idea of influence has been so devalued that it has been rendered meaningless.

Boorstin’s description of the dangers of self-deception in pseudo-events seems to prefigure today’s algorithmically driven social media feeds. “More and more of our experience […] becomes invention rather than discovery. The more planned and prefabricated our experience becomes, the more we include in it only what ‘interests’ us.” Boorstin’s fear that people would only see what they want to see in the print newspapers of the 1960s has come to fruition in today’s increasingly user-curated reality. The more we click on certain types of information, the more of it we see. As a result, our information bubbles get smaller by the day.

As we all know, the advent of digital media has also made it more difficult to find reliable information. Boorstin is careful to differentiate pseudo-events from propaganda. Put simply, “[w]hile a pseudo-event is an ambiguous truth, propaganda is an appealing falsehood. […] Propaganda oversimplifies experience, pseudo-events overcomplicate it.” A pseudo-event, such as a televised presidential debate, originates out of the honest desire to be informed. Such a debate will feed our “duty to be educated,” while a political speech, which can often be propagandistic, feeds on our “willingness to be inflamed.” Today, the two phenomena are often conflated, producing a culture of misinformation and perpetual outrage. This isn’t to say that there aren’t good reasons to be angry or causes worth fighting for. But genuine political discourse today gets lost in the noise of social media and round-the-clock news. We are inundated by a daily influx of pseudo-events and propaganda that is difficult to sift through. This is one reason why media theorists like Rushkoff and Sherry Turkle have been lobbying for a reinvigoration of honest conversation.

The views expressed in The Image do have their critics. In a 2012 article in the Los Angeles Times, Neal Gabler claimed that

Boorstin didn’t appreciate the adaptability of culture to circumstance. The fetish for images is not necessarily a blight on the world. It is its own thing — different from, not less than. Sometimes people don’t want the original. Sometimes they want the imitation, not because they are culturally brain dead but because they want release from the heavy hand of reality that Boorstin so revered.

Gabler makes an excellent point. For all his astute criticism, Boorstin may have overlooked our ability to grasp the problems he seemed to see so clearly. In a 2016 essay in The Atlantic, Megan Garber invoked the analogy of Plato’s Cave: “If Americans are living in a cave of our own making, even if we are offered the benefit of firelight, we might still choose the shadows.” In other words, given the choice, many may prefer the fake and manufactured to the true and realistic. As a lifelong fan of popular culture, I sympathize with the desire for fictionalized content; however, it is also important to know when we are looking at deceptive shadows on a cave wall. And just as Boorstin reminds us to be aware of the shadow casters, so some of the best popular culture draws attention to the shadows lurking in our world.

The original title of Boorstin’s book was The Image, or Whatever Happened to the American Dream? This always prescient question has new resonance in the digital era. On many levels, the American Dream has become an algorithmic nightmare. News today, largely driven by what politicians and pseudo-celebrities are tweeting, has been coupled with the personal and technological biases that drive online content. What Jon Stewart said about news being theater can now be applied to many forms of media. The desire to garner clicks, likes, and views by engaging and enraging audiences has taken precedence over the quality of content. Reading The Image in graduate school encouraged me to think about how information could be manufactured for nefarious purposes. What makes Boorstin’s argument so useful is that it does not get bogged down in political cheap shots. After all, ideologues of all stripes have the potential to get stuck in Plato’s Cave. And while Boorstin’s specific examples may be timestamped, his message about the importance of media literacy is timeless.

¤

LARB Contributor

Chris Yogerst, a regular contributor to the Los Angeles Review of Books, is an associate professor of communication at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. His most recent book is The Warner Brothers (2023). Chris is also the author of From the Headlines to Hollywood: The Birth and Boom of Warner Bros. (2016) and Hollywood Hates Hitler! Jew-Baiting, Anti-Nazism, and the Senate Investigation into Warmongering in Motion Pictures (2020). His writing can be found in The Hollywood Reporter, The Washington Post, The Journal of American Culture, and Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. Find him on Twitter @chrisyogerst as well as Instagram and Facebook @cyogerst.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Grim Purgatory: On Greg Jenner’s History of Celebrity

Aida Amoako considers celebrity through Greg Jenner’s history of fame, “Dead Famous: An Unexpected History of Celebrity from Bronze Age to Silver...

Truth Itself Becomes Suspicious: On Rob Brotherton’s “Bad News: Why We Fall for Fake News”

Athia Hardt reviews "Bad News," the new book from Rob Brotherton.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!