Pretending the Unhoused Away

Why Los Angeles’s special enforcement zones are a bad idea.

By Daniel PolanskyApril 11, 2022

IN THE 1920s, Herbert Croly wrote of the sense of malleability that prevailed across Southern California, a place “in which almost any kind of house is practical and almost any kind of plant will grow.”

A brief walk through Los Angeles’s Silver Lake neighborhood confirms this impression, showing off midcentury modern mansions poured from concrete, craftsman cottages, the ubiquitous (though essentially ahistorical) Spanish haciendas. From sun-decked patios, their owners look down on gardens that would be the envy of Babylon. In the heart of winter, vibrant begonias spiral up trellises, orange trees bend with fruit, and tentacles of agave burst into monocarpic bloom.

But keep heading south to where Glendale Boulevard meets the 2, slip beneath an overpass, and you’ll arrive at a triangle of concrete. There a posted sign informs onlookers in stern capital letters that they have entered a 41.18 “SPECIAL ENFORCEMENT ZONE,” and that sleeping, lying, and sitting down will not be tolerated. In the shadow of this sign, a group of tents are pushed up against a fence. One is owned by Lucky, who stops cleaning to speak with me.

She’s lived there for the last four years, she says, migrating up and down from the overpass when dump trucks come to remove her property. They put the 41.18 signs up a few weeks ago, but no one has been by to talk to her. The posted date for her removal was months ago.

Lucky is not alone in her confusion. Section 41.18 of the Los Angeles Municipal Code became law last July. For that vocal portion of the electorate frustrated with the growth of encampments in their neighborhood and desperate for some form of immediate action, it was heralded as a commonsense solution. Advocates for the unhoused saw it as a criminalization of poverty.

The “sweeps” that remove tents from sidewalks have long been common, but 41.18 differs in making certain areas permanently off-limits to the unhoused. According to a Los Angeles Times analysis, enforcing a 500-foot ban near schools, parks, and daycare facilities would make 49 percent of Hollywood and 46 percent of Skid Row off-limits for the unhoused. This does not account for other “sensitive use” zones, which include overpasses, underpasses, freeway ramps, tunnels, bridges, pedestrian bridges, subways, washes, spreading grounds, or active railways, virtually ensuring that any encampment in the city can be banned.

City Council members have effectively given themselves the ability to ban encampments within their districts at will, subject only to a rubber stamp from the rest of the council. Focusing efforts according to the famously incoherent boundaries that make up Los Angeles’s city council districts is like trying to put out a bonfire with an eyedropper. All these sweeps ordered by local potentates makes it more difficult to coordinate interagency efforts. “I haven’t seen a ton of collaboration in terms of checking in with service providers to actually see how this is impacting our clients or the work that we do,” admits Josh Hoffman of The Center, a nonprofit organization in Los Angeles County’s Coordinated Entry System “dedicated to ending isolation and homelessness in Hollywood”:

If a zone is enforced and clients are relocated without us knowing, that disrupts all the work that we were doing with that person. And that really is the case for any initiative that involves moving unhoused people around. Housing and shelter resources, they don’t just sit there waiting. If someone gets matched to something, we need to find them pretty quickly. Otherwise, they lose that possibility.

Enforcing 41.18 is probably illegal, and nobody wants to test it. Both settled case law and the city’s own homeless engagement strategy require that an offer of shelter be made to every individual in an encampment before it can be cleared — impossible so long as Los Angeles has some 40,000 more homeless people than it does beds to put them in.

“In this city, instead of housing people permanently and getting them off the streets, we have pushed people around from street corner to street corner,” says Councilmember Nithya Raman, one of two dissenting votes against 41.18. She continued:

The version of the law that we passed essentially does this, except you’re moving from one spot to another 500 feet away. We are not thinking about it in terms of where do we need to intervene as a city the most, how can we prioritize based on vulnerability … fire risk, or other kinds of public safety threats, on a set of characteristics that would be the same across the entire city to decide on locations for intervention.

That 41.18 is useless does not mean that it is harmless. A basic tenet of jurisprudence holds that it is unwise to enact a law which cannot be consistently enforced. Sporadic implementation is not only objectively unjust, but it also allows for selective enforcement. Arbitrary clearances are one of the chief complaints I hear from the unhoused. Not knowing when they are going to be cleared makes planning impossible and gives the unhoused the impression that these sweeps are punitive.

The corollary to Los Angeles’s unconstrained possibilities has always been a corresponding impression of unreality. “The city seems […] like an agglomeration of many variegated movie sets,” wrote the philosopher Paul Schrecker. Fantasy is as present in our politics as it is in our architecture and landscape, and the 41.18 law is the equivalent of a stucco facade on a faux Tudor mansion: it is the illusion of a policy, rather than a policy itself.

Though they sometimes truck in these daydreams, one suspects our leaders don’t really buy them. Mitch O’Farrell’s office, responsible for Lucky’s encampment, reports they have not enforced any 41.18 sites. Every other councilmember who responded to my questions says likewise. Several insisted that they were aggressively engaged in outreach at these sites, though none would comment on when enforcement might begin.

“In the presence of great wealth and natural abundance,” suggested Carey McWilliams, “poverty becomes absurd, anachronistic, insane.” Perhaps Eden demands its exiles, but the days of being able to restrict the unhoused to a carefully delineated stretch of metropolitan wasteland are long gone. There are simply too many of them, victims of our dysfunctional social services and a decades-long overheated housing market. Even Skid Row, the literal byword for urban blight, faces incursion from high rents inspired by the Arts District.

The only solution to this crisis is the rapid development of tens of thousands of low-income housing units. This will require reshaping our city in ways that many of us find unpalatable, but the alternative, tent cities choking our streets and armies of walking wounded, is far worse.

Seeing an encampment cleared away — the patch of pavement returned to sunlight, a stretch of sidewalk made usable — may offer an immediate sense of relief, but progress is entirely illusory. When an unhoused individual gets displaced, they do not hop a bus to Philadelphia. They move down the street. Lacking money and generally burdened by bulky possessions, they will join a pointless parade. Traditional mechanisms of compulsion are ineffective against people living in extreme poverty who can’t be fined, and posturing at City Hall won’t fix anything. You can legislate the clouds, but you can’t make it rain.

¤

¤

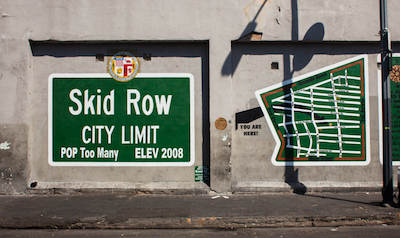

Featured image: "Phase 1 of Skid Row Super Mural" by Stephen zeigler is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Image has been cropped.

LARB Contributor

Daniel Polansky is a writer, baker, and advocate for the unhoused. He lives in Los Angeles. His most recent book is The Seventh Perfection (2020).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Art in the Speculative City: A Conversation with Susanna Phillips Newbury

Kate Wolf speaks to Susanna Phillips Newbury, author of “The Speculative City: Art, Real Estate, and the Making of Global Los Angeles.”

Uneasy Temporariness: Rosecrans Baldwin’s Los Angeles

“Everything Now” captures Los Angeles’s fundamental ambiguity, its magnetic swirl of beauty and darkness.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!