Plight and Parody: On Charles Johnson’s “All Your Racial Problems Will Soon End”

Andrew Montiveo examines the impact of award-winning author Charles Johnson’sfearless political satire cartoons from the 1960s to the 2010s, finding themes that are as relevanttoday as ever.

By Andrew MontiveoApril 25, 2023

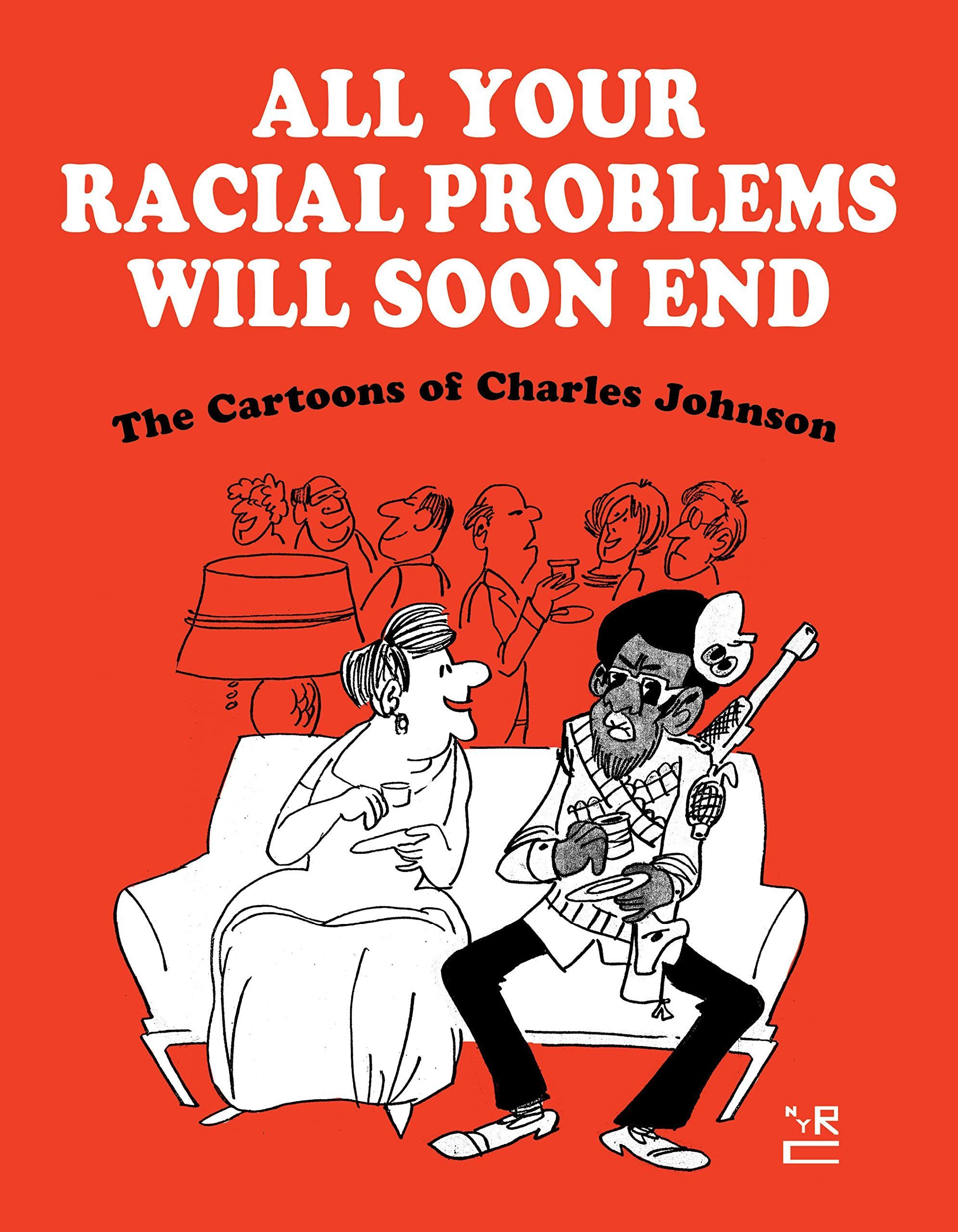

All Your Racial Problems Will Soon End: The Cartoons of Charles Johnson by Charles Johnson. New York Review Comics. 280 pages.

CHARLES JOHNSON is best known as an award-winning novelist: Middle Passage (1990) thrust him into the cultural limelight and the pantheon of American literati. Since then, Johnson has earned honors from the nation’s most prestigious institutions, such as the National Book Foundation, the American Literature Association, and the MacArthur Foundation. Prior to achieving such prestige, however, Johnson was—and arguably remains—a prolific cartoonist. Starting with local media in his native Illinois, he channeled his artistry into social and political satire focused on the key issues of the 1960s: racial strife, ethnic nationalism, and violent protest. Given how these issues endure, it’s clear that the themes in Johnson’s comics have legs. Long ones.

New York Review Books (through its imprint NYR Comics) has accomplished the mighty task of collecting most of Johnson’s cartoon satires into one hefty volume, All Your Racial Problems Will Soon End (2023). This collection organizes Johnson’s works into five sections spanning from the 1960s through the 2010s—though the bulk hail from the 1970s. This is unsurprising: Johnson published three anthologies between 1970 and 1973, two occupying a chapter each. ( Black Humor, his first collection, shares a chapter with his early works.) Given that the 1970s were the height of the Black liberation movement, much of the work offers various forms of parody focused on Black Power, Pan-Africanism, and white discomfort.

Much of this parody carries self-deprecation: Johnson was an avowed Marxist and an admirer of the Black Panther Party, but this doesn’t save the Panthers from his mockery. “[T]hey were dramatic, brash, Marxist, and oh so very visual with their berets, guns, and leather jackets,” he notes, and “their iconography was simply too rich for me, as a cartoonist, not to want to draw.” The Black Panther is the archetype for many (if not most) of Johnson’s caricatured militants. This figure is dashing, proud, and courageous, standing up to the police, protesting injustice, and shouting for an always-elusive “revolution.” Conversely, he’s also brash, crass, and myopic. The only thing he seems to fear is marriage: “It’s not that I don’t want to get married—it’s simply that marriage is an archaic white institution—and we can’t participate in that, can we?”

Less glamorous is the character of Jackson, a recurring Black protagonist who finds himself in comedic (and sometimes dangerous) binds. Johnson positions him as a butler to a haughty aristocrat, a disgruntled office worker, and a grunt socializing with a Vietnamese guerrilla in the jungle. Jackson’s fortunes don’t pan out: in the end, we see him promoted to captain of an ocean liner—just as it’s sinking, the former captain is shown fleeing in a lifeboat.

One gathers the sense that Johnson saw fatigue in the Black Power Movement by the early 1970s. By that time, the movement had already fractured: the Black Panther Party, the Black Liberation Army, and the New Afrikans (to name just a few) were divided by conflicts. One cartoon shows a wealthy Black socialite cackling, “Black Revolution? What Black Revolution?” Another shows two worried radicals looking over a complex scientific equation on a chalkboard. “According to my calculations,” one says, “we can expect a revolution in this country around 2962 AD.”

¤

The bitterest cartoon shows a flustered man conversing with an alien ambassador. “Take you to my leader? How? Malcolm’s dead, Martin’s dead, Rap’s in jail, Eldridge in exile.” This is the closest we come to seeing explicit sadness in Johnson’s works, an instance where satirical balance slips into tragedy. Many prominent Black social leaders, moderate and radical alike, had met violent ends by 1970: Medgar Evers in 1963, Malcolm X in 1965, Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, and Fred Hampton in 1969. The new decade left Black Americans without a unifying, policy-changing figure to rally behind.

Even had there been, social idealism and political capital had largely evaporated. The March on Washington, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society fell short of achieving racial harmony, civic peace, and an end to poverty. Early optimists, LBJ among them, anticipated that the nation could legislate and fund its way to interracial harmony. Riots, bombings, and assassinations proved their logic wrong.

Even Pan-Africanism saw its allure diminish into absurdist fantasy. “So Marcus Garvey beat the mail fraud rap,” a father tells his son in one of Johnson’s cartoons, “and moved all us black folks to Africa and we lived happily ever after!” If only there were a promised land across the Atlantic. Was it Joseph Mobutu’s Zaire, Samora Machel’s Mozambique, or Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya? Those who did flee to Africa found far less than paradise: Nina Simone found psychological descent in Liberia, Eldridge Cleaver found a surveillance state in Algeria, and Stokely Carmichael found himself imprisoned in Guinea.

¤

Of course, the United States has often fallen short of its claim to being a beacon of liberty, even to Americans who fought for it. When Johnson started his career as a cartoonist, the country was still in the process of racial desegregation; this can be seen in one of Johnson’s comics depicting a Black soldier stationed overseas, calling home outside a base’s segregated restroom, assuring his folks that he’s doing his duty “safeguarding freedom and democracy.” Black soldiers have served in the United States’ wars since independence, but service hasn’t always found gratitude. Organizers discouraged Black Union Army veterans from attending the 50th-anniversary reunion of the Battle of Gettysburg. Fast-forward to 2020: a Virginia police officer pepper-sprayed a Black army lieutenant during a traffic stop—despite the soldier not resisting.

Granted, that young lieutenant fared better than many other wronged Black soldiers. James Neely died in the last month of the Spanish-American War—not in combat, but in Georgia by an angry white mob after he complained about not being served at a local drugstore. Clinton Briggs came back from the trenches of World War I only to be shot dead and left hanging by a chain. His crime? He refused a white woman’s demand that he get off the sidewalk. Lamar Smith was a fellow veteran of World War I killed by his countrymen after he urged other Black voters to participate in a local runoff election. Felix Hall, an army private, was lynched on his base in 1941.

That’s not to mention broken promises, none more bitter than those made during the American Civil War. Johnson hearkens back to General William Sherman’s Special Field Order No. 15 when two militants hold up a Brinks armored car. “It’s either this,” one tells the Brinks driver, “or forty acres and two mules.” Apparently, the debt was due.

¤

Interracial romance provides another recurring theme in Johnson’s work; interracial marriage was taboo in 1960s America, when anti-miscegenation laws were still in effect. The US Supreme Court’s decisive verdict in Loving v. Virginia only came in 1967, and it took far longer for such relations to become normal. Johnson shows that discomfort over mixed relations is not limited to one color. One of his cartoons shows a Black couple in discussion as their son comes home with an extraterrestrial girlfriend. “And just what’s so terrible about Junior’s mixed dating?”

Black or white, there is always someone or something that falls outside the bounds of acceptability. If it isn’t the color of one’s skin, it’s gender, religion, or— the less pronounced—ethnicity. That last item is full of nuance—many people define race solely in terms of skin color. For example, Whoopi Goldberg showed lack of nuance with her recent insistence that the Holocaust “isn’t about race.” Instead, she claimed, the most significant act of genocide was simply “white people doing it to white people.” Goldberg’s remarks don’t come off as heartless; they come off as narrow-minded. Teuton and Slav? They’re the same. Arab and Kurd? Same. Good luck telling that to an Armenian and a Turk. Better yet, tell that to a Hutu and a Tutsi.

¤

Some of Johnson’s themes have a more conflicted resonance a half century on. One of his early cartoons shows a youth pushing back against the towering figures of Uncle Sam, academia, organized religion, and the press. “Why don’t you let me do my own thinking?” the youth cries. Many readers may empathize with this image. Isn’t freedom of thought the most precious liberty of all?

Unfortunately, today it is often reactionary figures—such as COVID-19 deniers, anti-vaxxers, climate skeptics, anti-feminists, and white supremacists—who cry the loudest in favor of “free” thinking and anti-establishment resistance. In many ways, this illuminates how deeply the liberatory momentum of the Civil Rights Movement and other progressive 1960s countercultures have now been co-opted by nearly everyone, for almost any purpose. Johnson could never have foreseen this, and his critique—in its historical context—hits the mark. Yet in our contemporary moment, when Trump supporters, Proud Boys, and Oath Keepers all unironically imagine themselves to be free thinkers fighting back against the establishment, it’s troubling to see how the sentiment Johnson articulates has become weaponized by far-right figures in ways he certainly never could have anticipated.

¤

Johnson’s later cartoons veer far from the militancy of his formative years. As he explains:

[M]y early study and teaching of Marxist philosophy eventually fell away in my mid-twenties […] political radicalism was replaced by a deepening commitment to an even more radical (in my opinion) Buddhist practice. Its emphasis on non-duality, loving kindness (metta) toward all sentient beings, and constant examination of my own presuppositions, premises, assumptions, and prejudices through mindfulness training proved to be antithetical to Marxism.

However, even Johnson’s shift toward Buddhism shows no abatement from his biting and effective parody. Instead of dodging gunfire or sassing cops, his later subjects tend to be aspirants blinded by extreme asceticism or the pursuit of instant enlightenment. The faith and politics may be different, but cluelessness still pervades. If there’s one takeaway from All Your Racial Problems Will Soon End, it’s the satisfaction that Charles Johnson’s humor has been on point for over 60 years. Here’s to hoping that he keeps us amused for many more.

¤

LARB Contributor

Andrew Montiveo is a writer in Los Angeles. A graduate of film at UC Irvine, he has written for Bright Lights, Cineaste, and The Worcester Journal.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Graphic Medicine: Comics Redraw Health Narratives

DW McKinney explores a recent spate of graphic-medicine narratives that deal with mental health and other medical issues.

Memento Mori: On Lauren Haldeman’s “Team Photograph”

Lee Thomas takes a look at Lauren Haldeman’s experimental graphic novel “Team Photograph.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!