Play Me Some Mountain Music: On Emily Hilliard’s “Making Our Future”

Tom Zoellner reviews Emily Hilliard’s “Making Our Future: Visionary Folklore and Everyday Culture in Appalachia.”

By Tom ZoellnerMarch 20, 2023

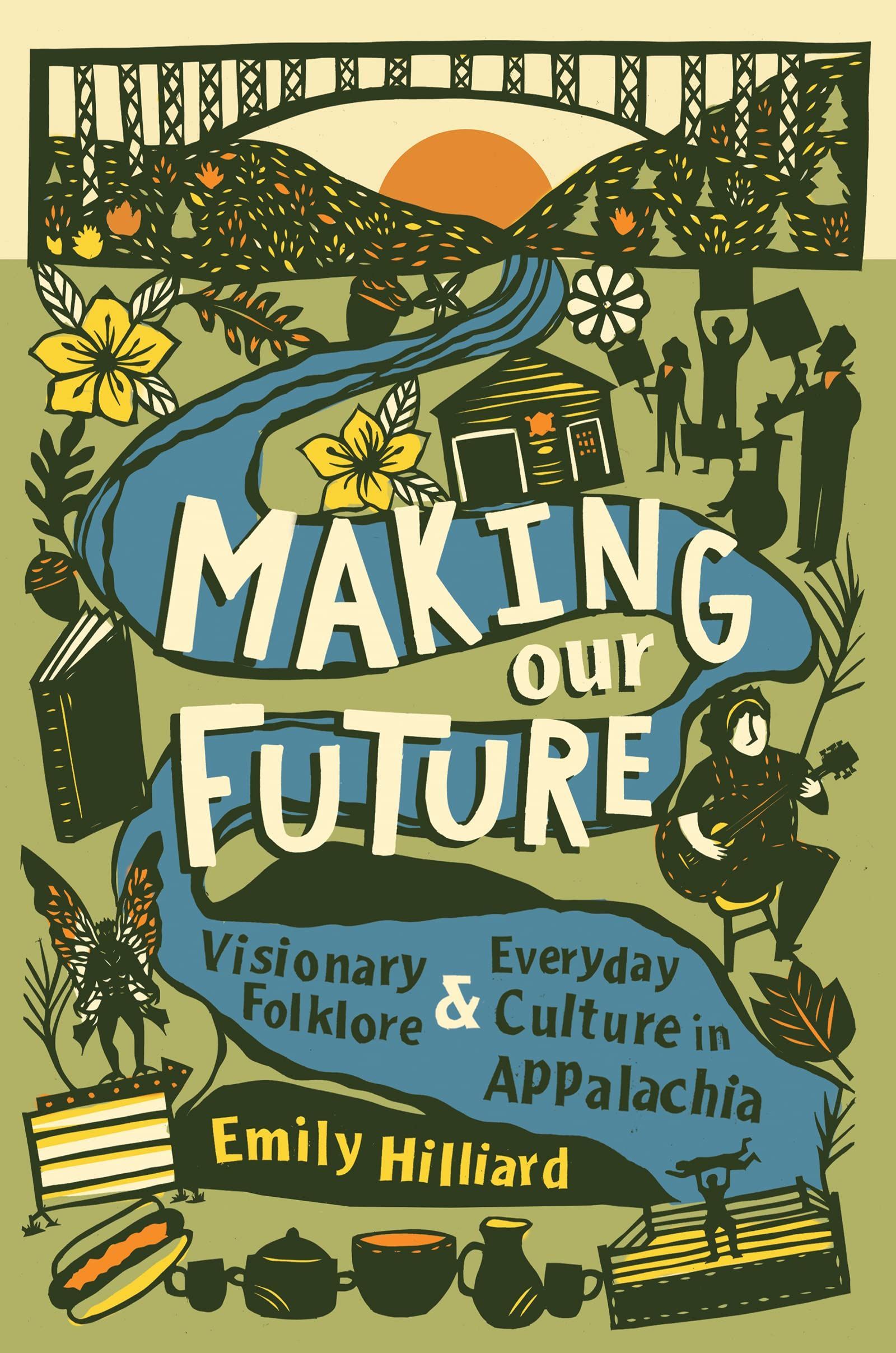

Making Our Future: Visionary Folklore and Everyday Culture in Appalachia by Emily Hilliard. The University of North Carolina Press. 312 pages.

DURING THE boredom of the pandemic, I indulged the bad habit of getting into beefs with Trumpers on Facebook. Many were people with whom I’d gone to high school in Arizona, but a few were friends of friends and even total strangers.

I’d giggle like a grade schooler at the juvenile bon mots and playground imprecations flung both by me and toward me, telling my real friends that none of the brawling should be taken seriously. It wasn’t meant as a form of political persuasion, only lowbrow entertainment. “Think of it like pro wrestling,” I would say. “People are playing extreme roles of themselves, just for sport.”

A curiosity of flame wars is that if you communicate with an enemy via DM, the conversation becomes far more cordial and even respectful. Such was the case when I started talking privately with one of my most capable antagonists, a guy from McDowell County, West Virginia, where I had distant family connections.

Joey Crigger had routinely disparaged me as “the idiot” and “Tombo,” amongst other names too delectable to be printed here. I mentioned my pro wrestling analogy to him.

“Why did you say that?” he asked.

“Seems like an apt comparison.”

His reply stunned me. He was a professional wrestler, on the thriving small-town circuit in West Virginia, as a side hustle to his regular job as a coal-mine electrician. He performed on weekends and at county fairs under the stage name “By God,” as in the unofficial state moniker “West by God Virginia.”

Crigger’s trash talk directed at me and my liberal ways was not just extemporaneous venom but a practiced art form, a kind of folk poetry. A broadcaster once called him “the Picasso of cheap-shot artists.” It was an honor to be so traduced.

Turns out the taunting discourse of pro wrestling in Appalachia—which flourishes there in community centers as in no other part of the country—is rooted in a mountain tradition of stylish insult that goes back more than a century. There is even a formalistic quality to the over-the-top bragging and physical threats, writes Emily Hilliard in her wide-ranging book Making Our Future: Visionary Folklore and Everyday Culture in Appalachia (2022).

“In the early nineteenth century,” Hilliard writes,

boasts of masculine dominance, with audacious claims and comparisons to dangerous animals and powerful inanimate objects, were employed by working-class men turned folk heroes like East Tennessee frontiersman Davy Crockett and legendary Ohio and Mississippi River boatman and brawler Mike Fink, who taunted, “I’m half wild horse and half cock-eyed alligator.”

In the logging and coal camps of 19th-century West Virginia—places where working people were routinely abused by absentee capitalists—the oppressed retained a sense of dignity for themselves through overt expressions of physical dominance and verbal supremacy. Reports of dirty fighting and “eye-gouging matches” emerged in big city newspapers, and historian Elliott J. Gorn wrote with a touch of hyperbole about “battle-royals so intense that severed eyes, ears, and noses filled bushel baskets.” But the modern era began in 1954 when the Oak Hill station WOAY started broadcasting Saturday Night Wrestlin’ in grainy black-and-white to the southern part of the state.

Appalachian pro wrestling is one of eight case studies on mountain pop culture taken on by Hilliard, a former federally funded folklorist for West Virginia and the founding director of the West Virginia Folklife Program.

Hilliard notes that wrestlers such as my frenemy Joey Crigger style themselves as “localized folk heroes,” taking on the role of the people’s tribune against the forces of evil, usually coming from the manipulative world beyond. (This often translates as a virulent strain of anti-Washington rhetoric in state politics.) The Saturday night face-offs between the hero and the deliberately fashioned villain, or “heel,” are, she says, “an easily discernible battle of binaries that, through an injection of high camp, transcends the two wrestlers in the ring to stage a moral and political battle between the forces of good and evil.”

More theater than athletics, these matches regularly draw crowds of 300 people in towns not much bigger than 3,000, and the competitors are paid about $40 for their troubles. Almost everyone understands that the punches aren’t real. The point is a good “fight narrative” leading to the collective expulsion of pent-up id. This is a welcome spectacle in a region that has been treated as an internal colony since the end of the Civil War, bruised by the unchecked flow of opiates and the withering of the mining economy.

“We’re the greatest psychologists in the world,” Jan Madrid, a self-styled heel, told Hilliard. “The average working person can’t afford a psychologist, but he can release all that emotion at a wrestling match.”

In a departure into theory, she calls it the “performative subversion of power,” a play space where real problems are crystallized into clear symbols: “While wrestling may champion violence, it also defies real-life material conditions by asserting control over that violence and converting it to a safe spectacle of entertainment.”

In another intriguing case study, Hilliard details the history of the West Virginia hot dog, a working-class lunch brought to the state in the 1920s by Greek immigrants, customarily slathered with coleslaw and a thin, hot chili sauce, distinctly unlike the traditional Chicago dog. But just as a loaded Chicago dog is “dragged through a garden,” or piled with tomatoes, peppers, and pickles, Hilliard pauses in several places throughout the book to drag her excellent source material through a forest of impenetrable academic prose.

All but the most hardcore of folklife scholars, for example, will want to skip the introduction, a deadly discussion of something called “intangible cultural heritage,” caged within sentences that agonize over “folklore’s collaborative ethnographic methodology, committed to equity and dialogue between fieldworker and the community or interviewee, referred to as the consultant or collaborator.” Such boulders of indigestible prose create distance between Hilliard and her intriguing subjects, who deserve more accessibility. The book would have been better structured as an exercise in narrative journalism, as she is sharpest as an interviewer and an observer.

Hilliard’s loveliest chapter is dedicated to the legacy of Breece D’J Pancake, a promising writer of short stories who killed himself with a shotgun at the age of 26. Book-minded residents in his hometown of Milton, reified as “Rock Camp” in his stories, have set up an informal tour of Pancake’s elementary school, a shuttered diner, and other sites important to his formation, where he picked up, among other things,

the vernacular language and verbal art shared on porch stoops and hunting camps, the occupational culture of farmers and miners, truckers and riverboat men, the superstitions related to weather and livestock and babies cursed by the evil their mothers encountered while pregnant, and the foodways of sorghum cane boils, fish roe, and jars of moonshine.

An image of Pancake diffused in afternoon light haunts this well-written chapter.

Teased by some as a “flatland foreigner” from Indiana, with a degree from the University of North Carolina, Hilliard answered an ad to become the state folklorist. She is nevertheless in an excellent position to observe her surroundings, able to see things from a curious outsider’s perspective and with a degree of freshness that lends authority to her observations. Not once does she condescend.

Hilliard also makes the excellent decision to forgo traditional centers of folklife, such as quilting, blacksmithing, fiddling, or barn painting, instead looking into milieus that might be easily dismissed as too new or lightweight to warrant critical attention, such as the apocalyptic multiplayer video game Fallout 76 or the surprise teachers’ strike of 2018.

I asked my internet foe Joey Crigger about some of Hilliard’s theories on the psychology of Appalachian-style pro wrestling, and he agreed about the long tradition of performative braggadocio. “I run my mouth so people will come watch me wrestle,” he said. “And it works. We call it ‘talking people into the building.’ People have come all the way from Kentucky and Indiana to watch me get my teeth kicked in.”

Sometimes, he went on, the trash talk gets a little too intense, and he and his opponents have had bottles thrown at them or threats made against them in the parking lot. The real point, though, is to let the audience get their own frustrations out by watching a burst of testosterone explode harmlessly in a small-town gym. “It’s a male soap opera, pretty much,” Crigger said.

Hilliard writes that charting West Virginia folklore is an act of faith in the future: a cataloging of present-day culture for people down the line who might spin it or play with it in other ways. Such is the wonderfully alive nature of regional popular memory. It pushes itself forward even as it emerges from a shared past. A scholar she quotes talks about “anticipatory heritage.” West Virginia is lucky to have Hilliard and, a few servings of pedagogical molasses aside, can anticipate even more valuable work from her in the future.

¤

Tom Zoellner is the politics editor for Los Angeles Review of Books.

LARB Contributor

Tom Zoellner is an editor-at-large at LARB and a professor of English at Chapman University. He is the author of eight nonfiction books, including The Heartless Stone: A Journey Through the World of Diamonds, Deceit, and Desire (2006), Uranium: War, Energy, and the Rock That Shaped the World (2009), The National Road: Dispatches From a Changing America (2020), Rim to River: Looking into the Heart of Arizona (2023), and Island on Fire: The Revolt That Ended Slavery in the British Empire, which won the 2020 National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonfiction and was a finalist for the Bancroft Prize in history.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Tom Kromer, Appalachia’s Forgotten Modernist

Tom Kromer’s “Waiting for Nothing” is one of the great American novels you’ve never heard of.

It’s Just a River Rivering: A Conversation with Mesha Maren

Katie Smith talks with Mesha Maren about the settings and authors that inspired the complicated border fatalism of “Perpetual West.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!