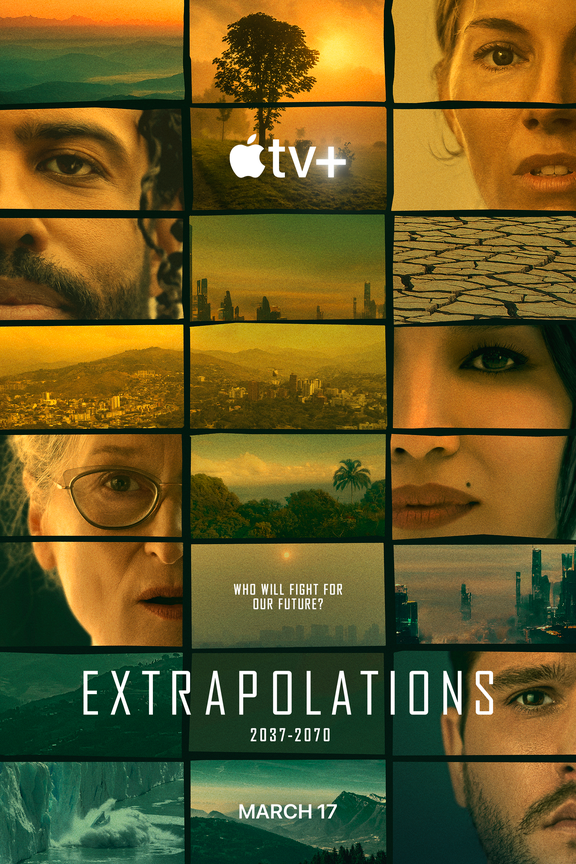

Pathos Porn About Climate Change: On Scott Z. Burns’s “Extrapolations”

Aaron Bady reviews Scott Z. Burns’s new climate change series “Extrapolations” (Apple TV+).

By Aaron BadyMarch 25, 2023

SCOTT Z. BURNS’S new Apple TV+ show Extrapolations is, like climate change, bad. And like climate change, it’s bad in so many different ways at once that it defies easy summary. Sometimes it’s so bad that it’s almost good, as when an atmospheric river blasts California’s infrastructure but also refills drought-emptied reservoirs, or when Matthew Rhys’s character is gruesomely and inexplicably (and hilariously) killed by a walrus. But mostly, it’s like climate change because it’s a depressing experience that goes on for a long time.

One way it’s not like climate change is that Extrapolations—a prestige speculative fiction series about the future global apocalypse—is focused mostly on the emotional turmoil of rich Americans. You might have missed this because the first episode, set in 2037, sprints through such a dizzying array of settings—Israel, Russia, the Adirondacks, the Arctic, and a billionaire’s bunker in an undisclosed location—that there’s no time for viewers to catch their breath, much less for writers to tell a coherent story. Characters speak in cramped exposition, and the episodes are so compressed that the show ushers confrontations, catharses, and soliloquies on- and off-stage with assembly-line efficiency. And yet, far more of the show’s protagonists than not turn out to be wealthy Americans struggling with their consciences, weighed down by self-loathing and shame. A brutally basic fact about the world’s looming future is that the Global South—in particular, the three-quarters of humanity who live in Africa and Asia—will bear the brunt of it.

Why, then, is this a show about rich people in the West who feel bad, in comfort?

¤

Maybe the answer is simple. Maybe I’m the one being tedious by imagining that a series about a planetary crisis should have more than one—admittedly well-made—episode whose protagonist isn’t some variation on “rich American.” Maybe I should lower my expectations for what Apple TV+ can do and just buy a ticket to see Daniel Goldhaber’s new film How to Blow Up a Pipeline instead. Maybe Extrapolations is exactly the kind of show you’d expect a corporation like Apple to make: one that centers the pathos of the privileged, holds protesters and the Global South at a suspicious arm’s-length, and “raises awareness” about the consequences of climate change while saying as little as possible about fossil fuels.

Let’s start there. How do you make a show “about” climate change without focusing on fossil fuels? How do you speculate about the future that climate change is making without grappling with the material forces that are shaping that timeline? It’s easy, as it turns out. You bunker away your overwhelmingly American protagonists in technologically sanitized interiors, make them sad about the future, and, though they breathe the smoky air like everyone else, give them access to clean water, delicious food, and a variety of magical machines that make their lives easier. You make sure that, while “climate catastrophe” hovers at the edge of every story, the actual stakes of those stories are always the strained relationships between parents and children (who either die or are at odds, or both). When you allow an angry voice (usually young people, who are usually kind of annoying), you make sure that they vaguely blame “us”—“humanity,” “corporations,” and “capitalism” in the broadest (and shallowest) possible terms. Most importantly, you set your show decades in the future so that it can feel a bit too late to worry about the whys and hows. After all, if you tell a story in which we’ve already blown well past the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s infamous 12-year window, then what is left to do but cry at the funeral and profit from it? Burns himself did a lot to bring concerns about fossil fuel consumption into mainstream debate as a producer of 2006’s An Inconvenient Truth. But now, in 2023, Extrapolations leapfrogs over those antiquated turn-of-the-century concerns to focus on characters who agonize over whether it’s right to profit from the ruined world that fossil fuels helped to create.

This, I think, is the basic problem with the show: the conflicts that drive its narratives are variations on the question of whether it’s justifiable to make money from the apocalypse. Perhaps Burns knows, in his bones, that this is what the show is doing. But its emphasis on the pathos and self-hatred of comfortable Americans squanders whatever political charge its subject might have given it; beyond climate change being really, really bad—and families being really, really important—it doesn’t have much of anything to say. This is not an activist show that knows what we should do about climate change, right now, and tells us; this is a fatalistic show about what the consequences will be when we don’t do anything at all. It’s a show about comfortable rich people who, while they worry about the future in some abstract sense, also, in a much more concrete sense, do nothing of substance to avert it.

On some level, the show must understand the problem. After all, the first episode opens with an exception to everything I’ve just said: we see Carmen Jalilo—a kind of born-in-2015, POC-Greta-Thunberg-of-the-future figure played by Yara Shahidi—preparing to holographically address protesters around the world, shouting crowds that will haunt the rest of the episode. As she is rehearsing what she will say, and they are all the right words, she is asked by a technician if there’s anything she needs. “For people to listen,” she murmurs, and although she says it with the kind of intense, off-putting seriousness that Hollywood always gives to activists, this is, in a sense, the show’s pitch: making a series about climate change—and viewers watching it—is “part of the solution.”

But what does the show really think of activists, masses, and collective action? To put it simply: As little as possible. For the rest of the episode, the protesters will serve as a moralizing, reproachful chorus, shouting from the streets at protagonists having conversations inside. They are a spectacle. There’s a deliberate echo of David Buckel in a character who self-immolates in front of a billionaire’s car, but the show doesn’t tell his story; we never learn who he or Carmen Jalilo is or where they’re from. In a very real sense, we can’t listen to them, because they remain ciphers, abstract stand-ins for serious protest archetypes, for the kind of activist consciousness that the show can’t ever seem to let itself access. Instead, Extrapolations is interested in the people who should listen to the activists but don’t, and from their perspective, the camera sees the mob as strange and unsettling, the disorder outside that one must sprint past on the way from one secluded interior to another. Unlike every other character in the first episode, Jalilo does not return in later installments, and we never learn what drove the nameless, masked protester to set himself on fire. Burns puts us in the car with the show’s privileged protagonists: horrified, bewildered, and comfortable spectators.

Perhaps the obvious correctness of these activists necessitates pushing them to the background, the better to tell the story of the people who aren’t listening. Perhaps there would be no drama if the show’s protagonists were simply right about everything from the beginning. But I must be merely overthinking it: maybe the protagonists are mostly privileged Americans because this is an American miniseries made for American viewers by American producers and writers and movie stars who are paid by an American corporation so huge that its (substantial) losses on scripted content can be written off as an investment in its brand. And Hollywood has never been kind to environmental activists; they make great villains because, as we all know, they want to take away your plastic straws and gas stoves and whatnot. Finally, it’s anything but surprising that a work of pathos porn like this would be uninterested in the alternative timeline where we heed the activists and leave the oil in the ground. To tell a story about the consequences of climate change, a show must tell the story of those who, in their passivity, allow it to happen. Maybe this is a gesture at self-critique, a radical mea culpa on behalf of this corporation and its corporate friends for their negligence. But then again, there’s another word for making yourself the center of every story.

Whatever the reason, the first three episodes of the show tell the stories of an interconnected group of rich inactivists. We follow Junior (Matthew Rhys), a kind of Donald Trump Jr. figure who is trying to build a casino in the (melting) Arctic, apparently at the shadowy behest of Kit Harington’s Nick Bilton, a Bezos-Gates-Musk figure who bends world governments to his will and profits from the environmental catastrophe. But while Bilton is the show’s main villain, all the other characters either work for him or benefit from his largesse: we follow an American who works for his futuristic zoo, collecting animals for their DNA; we follow COP42 negotiators who capitulate to Bilton and relax environmental regulations; and we follow a once-idealistic rabbi who—and you might detect a theme emerging—compromises his moral vision and allows himself to be bought (twice). This theme will continue until the final episode, when Bilton sort of gets his comeuppance; the only thread holding the show together, to the extent that there is one, is that all of the characters worked for—or were, in some way, pacified and placated by—his sinister beneficence. As a result, most of the storylines are structurally the same: shortsighted rich people pursue their own self-interest until, in the final act of their story—against the backdrop of a dramatic but ambiguous expression of nature’s awesome power (or the love of their lost children)—they realize the consequences of their compromise, and they regret it.

¤

This obsession with regretful compromise might be less annoying if the show had any clarity about the path not taken. But it doesn’t, and can’t, because it scrupulously avoids talking about the fossil fuel economy, an aversion that gets weirder and weirder the more I think about it. Greta Thunberg’s Twitter bio says that she was “Born at 375 ppm,” and David Buckel explicitly used fossil fuels to kill himself as a protest against fossil fuels; there is no group of human beings more relentlessly laser-focused on the fact that burning fossil fuels causes climate change than activists. Yet in Extrapolations, even the activists speak in a strangely euphemistic way about degrees of Celsius. “What happens when the corporations that are destroying our world say that our economies will fail if we don’t allow the temperature to rise by 2.1 or 2.2 degrees?” Jalilo demands, posing the question the show sets out to dramatize and answer. And of course, at the end of that episode, COP42 negotiators do, in fact, trade away fossil fuel restrictions in a murky exchange for patents on desalination technology.

If the show has a thesis, it’s that our original sin as a technological society is allowing billionaires to sell us Band-Aids for a crisis that they have an incentive to perpetuate; as Harington will eventually tell the audience in an Evil Villain Monologue (which the actor approaches with the appropriate scenery-chewing gusto), it is our fault for wanting comfort and pleasure and for desiring all the things that he, the capitalist economy helpfully personified, sells us. But the show has no time for thinking about what “we” should have done instead. Does the world have a giant thermostat, and if only “we” would make a few adjustments, the temperature would magically go down? One might observe that every world climate conference in the history of world climate conferences has agreed on some number to which it would be safe to let the global temperature rise, and then—in the absence of concrete restrictions on the extraction and burning of fossil fuels—those numbers have proved to be little more than temporarily comforting fictions, mile markers on the road to catastrophe.

The most terrifying thing about climate change, after all, is that, while we do have a roadmap of the coming future, you and I don’t have our feet on the gas pedal, not really. You and I haven’t “allowed” this to happen; we aren’t in control of anything. We drive to work because if we don’t work, we will lose our homes or health insurance, and because driving is usually the only way to get there. No one asks renters what kind of stove they’d like, and electricity utilities don’t poll their customers on what method of kilowatt generation they should use. Perhaps more to the point, the three-quarters of the world that live in Asia and Africa—who will suffer the most as the oceans rise and the biosphere sickens—have, historically, produced almost none of the carbon debt that now hangs like a corpse in our sky. To make a show about how “we” are guilty is to make the show the producers have made—not about humanity but about wealthy Americans. (The only exception—an episode set in India—is an exception in every sense: a refreshingly coherent story about normal and believable human beings that, as such, could not feel more different from the universe of the other seven episodes.)

If I’m being cynical, I think Extrapolations needs us to get lost in the self-regarding pathos of rich Americans because it might otherwise become a show about how horrifically simple this all is. The science on climate change was clear in the 1970s, and we know, in as much detail as we might want, how clearly the oil companies have always understood what they didn’t care to do. Joe Biden knows perfectly well that he shouldn’t approve massive oil drilling on federal lands in Alaska, because he campaigned on not doing so. We all know that burning fossil fuels causes climate change; we all know that we should, simply, not burn fossil fuels. To make it seem complicated, difficult, and confusing might ease the consciences of the compromised, and it certainly helps oil companies continue posting huge profits. But it’s not that complicated. It just isn’t. As formidable as the political task of decarbonizing the economy might be—or, better still, of reimagining it completely—and as logistically complicated and expensive as it will be to reduce our collective “carbon footprint,” the most depressing thing about climate change is how thoroughly we understand the problem and how clear the solutions now are. A lack of awareness of the problem hasn’t been the reason “we” haven’t solved it, now, for decades; corporate capture of state power—and the world they’ve intentionally built to make fossil fuel consumption mandatory—is a completely sufficient explanation for why you and I can’t just decide not to rely on fossil fuels.

I say all this because of the idea that climate change defies narrative, that it poses, as Amitav Ghosh has persuasively argued, a crisis of the imagination. Ghosh is a smart guy, and his 2016 book The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable is a compelling account of the challenges climate change poses for writers and readers. But Extrapolations doesn’t fail because of some underlying creative aporia; it fails for a much simpler reason, the same reason that Don’t Look Up (2021)—the other recent star-studded climate-change morality play—was such a wet flop. The problem is not climate change’s intrinsic resistance to being imagined and narrated; the problem is the kind of stories that corporate entities like Apple are willing to pay for.

After all, if you’ll pardon the tangent, everyone involved in making Don’t Look Up insisted that it was “about” climate change, but strictly speaking, it really wasn’t. It was about a comet that was about to hit the earth. And the thing about a comet hitting the earth is that the oil, gas, and coal companies cannot be held responsible for making it happen; as an allegory for climate change, it was one that made the threat external to our energy economy, literally alien to our entire way of being. (Adam McKay had to make this notably un-star-studded ad, in other words, because nowhere in his film would you learn that “we at Chevron straight up don’t give a single fuck about you.”)

I’m not sure what a good TV show or movie about climate change would look like. But both Don’t Look Up and Extrapolations blame humanity for our bad choices, and I know that this is not it. It’s worth remembering that the idea of individuals having a controllable “carbon footprint” was invented by British Petroleum—more specifically by their real-life Mad Men at Ogilvy & Mather—with a very specific goal: to shift the conversation about carbon emissions so that ordinary people would feel guilt and shame, and obsess over self-regulation, rather than scrutinize the actions of oil companies. If people felt bad about their choices, after all, they might not notice that their options were all bad; if they felt guilty, they might not feel rage at British Petroleum for destroying the world. By the same token, in the kinds of climate change movies that get bankrolled, the problem is always us—a baffled and divided public guiltily tracking its carbon footprint all over the earth—and only secondarily, almost as an afterthought, is it entities like Chevron or BP.

Meanwhile, for all the rhetoric of “if only people would listen,” even the American public is not nearly as divided on climate change as we imagine them to be. And if you expand that sample to include the rest of the world, what you find is that “people” more or less know what the problem is, and would like to solve it. We get stuck because “we” aren’t the constituency that matters; the consensus that dooms us is between the fossil fuel companies and the politicians they buy. As our political system is currently composed, they have a vote, and you and I do not.

¤

When I, the child of an environmental organizer, was a kid, the West Virginia Environmental Council made a T-shirt with a map of the state on the front, and every environmental hotspot they could think of marked with a dot. The caption was “we all live on a dot,” because the map was nothing but dots. The point was that there was no escape, no secure bunker, no protection from environmental degradation. We are all in the same boat, and because that boat is sinking, anything but collective action is nonsensical. And at least since the famous “blue marble

” photo

, this has been the central thrust of the environmental justice movement: to collectivize our imaginations, to organize communities of solidarity with the understanding that there are no gated communities in an ecological crisis.

Like Carmen Jalilo, this kind of politics lives offscreen in Extrapolations. Instead of telling the stories of anyone involved in creating or trying to solve the problem of climate change—instead of really being about climate change, in that sense—Extrapolations centers on characters who are motivated by selfish or family-oriented concerns; the climate catastrophe remains a kind of ambient background noise in their lives (when it isn’t foregrounded via bafflingly artificial exposition). In its obsession with guilt-ridden individuals (and their children), one might say, echoing Margaret Thatcher, that “there is no such thing as society” in this show—“there are only individuals and families.”

But “comfort versus climate” is a false choice, imaginable only by refusing to understand the interconnectedness of our lives and the fragility of our economy. Ecologies collapse, and when they do, economies—and the societies they sustain—crash. And while a certain subset of the billionaire class might plan to bunker themselves away from what’s coming, what are they going to eat when the cans run out? Who will guard them when their payroll checks are worthless? Of what value will all their gold and cryptocurrency be? They will breathe the same tainted air as the rest of us, and their bodies will fill with the same toxins. If the apocalypse comes, no one will feed them and no one will serve them; nothing they have will be worth anyone’s while.

On some level, I think Extrapolations insists that “climate versus comfort” is a choice, a question, and a damnable dilemma, because its creators can’t bear to imagine the full consequences of the events the show takes as its premise. It wants to believe that bourgeois comfort and security will still be possible in a climate-changed future, that class structures will endure, and that, as much as the world will change, it won’t really change. There will still be masses of poor people, but they will still suffer and die out there, as spectacle, while we suffer more mildly, indoors; we will feel guilty, in the future, because the worst consequence we’ll suffer is that our children will hate us. And so, the show insists that not only will billionaires still rule the world; they’ll continue to have technological pottage with which to buy us off. In Extrapolations’ hazily imagined future, after the most catastrophic consequences have already happened—from the end of bees, rainfall, and sea life to normalized wet-bulb events across the equator—bitcoin, of all things, continues. Animals and trees have become distant memories, but technological advances sprint forward: cancer is cured, deceased loved ones live on as holographs, memories can be uploaded to the cloud, the solar system becomes colonized. We even get flying cars.

What Extrapolations does, in other words, is fundamentally sever the link between the ecological base of all human life and our technological society, insisting that no matter what happens to the former, the latter will continue. Billionaires will still rule the world, and we’ll always have the poor; the economy will survive, because technology will keep it together. In this sense, the predictive vision that the show extrapolates is not that of the novels The Road (2006) or Station Eleven (2014) but something much more like Charlie Brooker’s ongoing series Black Mirror (indeed, the sixth and seventh episodes of Extrapolations could be released under that name and no one would notice the difference), a conceptualization of the future where everything has changed so much that nothing actually has to. So what if all the bees are dead? We’ll just pollinate crops with robots or eat kelp or something else that the future will invent. Have the oceans risen and inundated the world’s coastal cities? Don’t worry, we’ll just build walls. The earth is dying? We’ll just live in the stars and digitize our brains. And so, the most pernicious thing about Kit Harington’s evil billionaire character is not his plan to worsen the climate catastrophe so that he can profit from it; it is that Extrapolations still thinks he’s a genius.

¤

LARB Contributor

Aaron Bady is a writer in Oakland.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Back, Scoundrels: Eating the Rich on Film

Pat Cassels considers a spate of new class-conscious popular films, including “Triangle of Sadness,” “The Menu,” and “Glass Onion: A Knives Out...

Escape Therapy: On Douglas Rushkoff’s “Survival of the Richest”

Raymond Craib reviews Douglas Rushkoff’s “Survival of the Richest: Escape Fantasies of the Tech Billionaires.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!