Paranoia, Obsession, and Murder in Robert M. Coates’s “Wisteria Cottage”

Jack Mearns examines Robert M. Coates’s “Wisteria Cottage,” a midcentury psychological noir from an author too often overlooked.

By Jack MearnsJanuary 24, 2022

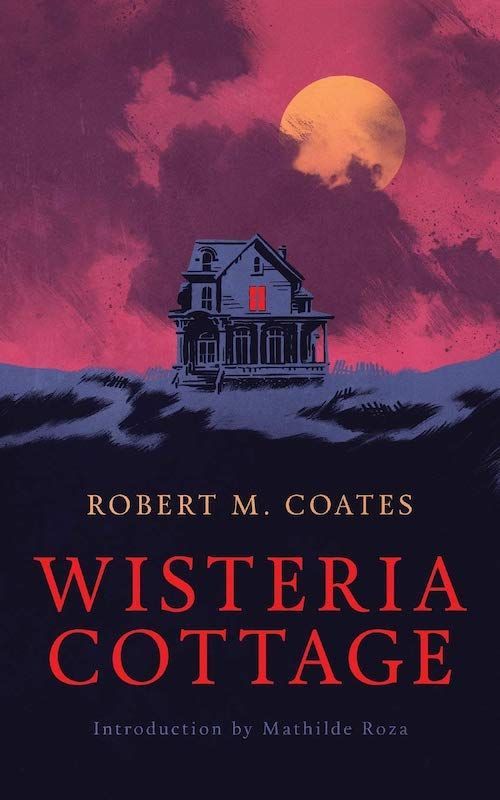

Wisteria Cottage by Robert M. Coates. Valancourt Books. 196 pages.

READING ROBERT M. COATES’S 1948 noir, Wisteria Cottage, has the dreadful inevitability of watching thunderheads massing on the horizon as the wind picks up late on a summer afternoon — skirts of rain beneath the blackening sky, flickers of lightening — knowing the squall will strike after sunset. The plot is simple, and from the outset we know death lurks in the final pages. Richard Baurie, a “boyish” Midwest transplant to New York and would-be poet, wants nothing more than to belong to a family. By insinuating himself among the Hacketts — a mother and her two adult daughters — Richard dreams of being “son, father, and husband rolled into one.” To keep these women all to himself, he hatches a plan for the family to rent an isolated house on the Long Island shore — Wisteria Cottage.

Wisteria Cottage shines with its vivid portrayal of the tensions that rankle relationships among family and friends — the unfulfilled longings and hopes — filtered through the deteriorating mind of Baurie as he struggles with encroaching psychosis. Baurie cannot resist his religious delusions, his sexual obsessions, and “the queer, powerful, lifting buoyancy of his anger.” He loves the Hacketts, he hates them, he fears them — “which was much the same thing” — because they represent everything he desires in life. He wants to be them; he wants to possess them. And yet, the filth and evil he fancies in them leave him no recourse but to save them from themselves. “I can cure you. I can remake you. I can make you whole again.” To be redeemed, they must be sacrificed.

What makes Wisteria Cottage so compelling is Coates’s mastery at recounting Richard’s descent into madness. He does so with a measured, aloof third-person voice that maximizes the ominous tension — the quiet before the storm. Coates subtly allows Richard’s disturbed thinking to infuse the narration itself, as even descriptions of scenery are distorted by Richard’s disordered faculties. In the first few pages, there is “the almost listening calm” of the sea, “like a great glistening eye aslant, watching him balefully.” The most sensational aspect of Wisteria Cottage is its complete absence of sensationalism. In the words of one contemporary reviewer: “Coates manages to isolate in its pure form, to an extent rarely matched by other writers in the genre, the quality of horror. He does this without ever, as it were, raising his voice.”

¤

Though Robert M. Coates is largely unknown today, he was an admired stylist in the mid-20th century. A mainstay at The New Yorker, he contributed over 100 short stories to the magazine and was its art critic for 30 years. New editions of Coates’s three best novels offer today’s readers a reintroduction to a precise and skilled innovator, who pushed the boundaries of narrative to convey the tumult of modern life.

Coates was born in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1897. His father was a toolmaker and inventor, whose wanderlust took his wife and only child far and wide across the United States, leaving a trail of failed ventures in his wake. Coates attended Yale University, interrupting his studies for flight training with naval aviation on Long Island Sound.

Like many Ivy League graduates of that era, Coates entered the burgeoning new field of advertising. However, yearning to be a writer, he soon retreated to a shack in Woodstock, New York. Coates’s father visited and was so appalled by the squalor he observed that he funded the son’s passage to Paris. After his 1921 arrival, Coates plunged into the hurly-burly literary life of the City of Light, where he found affinity in particular with the Surrealists and Dadaists. But Coates remained, in the words of one contemporary, “a lone wolf.”

Coates befriended other expatriates, such as Malcolm Cowley. He was Gertrude Stein’s favorite among the young American Lost Generation writers. He boxed and played tennis with Ernest Hemingway. At Stein's urging, Robert McAlmon published Coates’s first novel, The Eater of Darkness, in his Contact Editions. In 1929, after Coates had returned to the United States, Macaulay issued a hardback, with a lurid jacket depicting the map of Manhattan transformed into a google-eyed monster. The Eater of Darkness defies classification: it is science fiction, crime story, and literary satire rolled into one. Mad scientist Picrolas enlists protagonist Charles Dograr in a spree of murders, using a fantastical weapon that destroys people’s brains at long distance with an “x-ray bullet.”

Cowley called the book “the first purely Dada novel to be published in English.” As such, The Eater of Darkness represents an anarchic thumbed nose at the literary establishment. Coates wrote in an introduction for a 1959 reissue, “Dada has always meant gaiety: the one artistic movement […] whose main purpose was having fun.” And fun Coates had, with a host of surrealist tropes that would not be out of place in contemporary postmodern fiction: interpolating advertisements and using a footnote to reflexively lambaste himself for letting the novel get away from him — “The complete ignorance on the part of Mr. Coates of the most elementary principles of plot construction, apparent through the book, is here devastatingly revealed.”

Critical reaction to The Eater of Darkness was polarized, depending on which side of the advancing wave of modernism the reviewer was on. One stodgy old-guard critic complained: “Mr. Coates does not take his novel seriously; so why should we?” By contrast, those who were in on the modernist joke found the book delightful. One reviewer wrote of his “thrill” that the victims of Picrolas and Dograr included seven of the era’s most prominent book critics. Another enthusiast stated that Eater is “unique and invaluably funny. […] The footnotes alone are worth the price of admission.” City Point’s reissue includes Coates’s 1959 introduction and a new, illustrated introduction by Coates expert Mathilde Roza.

Murder and mayhem were prominent themes in Coates’s work from the beginning. In his follow-up to The Eater of Darkness, Coates gave them full rein. The Outlaw Years (1930) is a nonfiction account of the bloodthirsty land pirates who preyed upon those traveling the Natchez Trace — the wilderness trail paralleling the Mississippi River — in the early 1800s. Coates used his Outlaw Years royalties to buy land in Sherman, Connecticut, where he built a house among an enclave of artists and writers who had fled New York City. The competing lures of rural versus urban life would remain a defining element of Coates’s writing.

Coates’s second novel was Yesterday’s Burdens, published by Macaulay in 1933 (reissued by Tough Poets). That Yesterday’s Burdens is forgotten today is tragic, for it is a modernist masterpiece so stylistically audacious that it still feels fresh and new 90 years later. Just as James Joyce endeavored to capture the sights and sounds of Dublin in Ulysses, Coates sought to evoke New York City and its environs at the advent of the machine age, which bombarded people’s senses with stimuli. Yesterday’s Burdens also anticipates the departure of city dwellers for the suburbs and the crucial role of the automobile in that migration. One of the novel’s most typographically bold passages portrays a drive from country to city, with the parkway’s signage physically entwined with the narrative.

Yesterday’s Burdens commences with a gorgeous description of a year in the country’s cycle of seasons, which reviewers likened to Henry David Thoreau’s Walden. A sentence like, “These are gusty, blustering, flustering nights, when it seems that anything might happen,” reveals how early Coates began experimenting with the animistic melding of psychology and nature that would flourish in Wisteria Cottage.

Yesterday’s Burden is nearly plotless. As Coates reflexively states early in the narrative: “[L]et me tell you about this book I’m trying to write. […] It’s a novel, or rather a novel about a novel, or perhaps one might better describe it as a long essay discussing a novel that I might possibly write.”

Malcolm Cowley marveled — in an afterword for a 1975 reissue, reprinted in the current edition — that Coates “is like a conjurer laying his cards face up on the table […] confident that there are enough tricks up his sleeve to keep the audience amazed.”

While some reviewers were baffled by the complexity of Yesterday’s Burdens, The New York Times hailed it as “ostensibly a novel, but […] in reality everything under the sun […] like looking down endless facing mirrors […] a rare elixir.” The Chicago Sun pronounced it “one of the finest, most sensitive and most deeply moving novels of the last two decades.”

Coates’s next book was 1943’s All the Year Round, a short story collection in which he explored themes that would reappear in Wisteria Cottage — the appeal of the countryside for urbanites; the yearning among an alienated populace for belonging; the need for people to have a sense of power over others; and the potential for ordinary folk to commit violence, suicide, and murder. The most famous of these stories is “The Fury,” whose child molester protagonist can be seen as a study for Richard Baurie — his viewing other people’s sexuality as filth, his belief that he can control others’ wills, his paranoia, and his vengeful violence. Coates’s unflinchingly close depiction of the man’s attempt to lure a little girl away still chills the blood.

¤

Wisteria Cottage weaves together the many strands of Coates’s writing career. There is the brutality that permeated much of his work and the intimate portrayal of desperation that suffused his most affecting stories. In a reprise of his sublime depiction of the seasons in Yesterday’s Burdens, there are sumptuous descriptions of summer, progressively tinged by Baurie’s disintegrating mental state. Early in the book, Coates writes:

Summer is a happy time, but it is a harrying, hurrying time, too. It is a mixed time. Haste and laziness are mingled; it is a time when time seems to stand still, and each day is like every other day, and yet different; it’s the time when the calendar almost, but not quite, supersedes the clock, and you think in terms of days instead of hours, of whole seasons instead of days.

By the end, the season itself becomes menacing and unhinged:

But the summer is a nervous, testy, unstable, uneven time, too. It’s a time when anything can happen. […] It’s a time of thunder, the summer, when the weather itself gets beyond control and goes prowling, prowling, prowling around the hazy undulations of the sky line while the heat and the excitement lie closelier and closelier compacted.

It is as if the author has allowed his very novel to go insane.

Wisteria Cottage was enthusiastically embraced by critics. “A brilliant tour de force,” one proclaimed, noting Coates’s “exquisite control of verbal nuances.” Another offered: “Coates writes with an un-self-conscious economy that by its uncluttered line is trenchant and unexpectedly moving […] as direct and frightening as the uncoiling of a serpent.”

Compared with today’s thrillers dripping with gore, Wisteria Cottage’s carnage is tame. The novel’s thrills derive, instead, from helplessly witnessing Richard Baurie’s deepening madness, while his adoptive family blithely whiles away their summer at the shore. The climax of the novel is no mystery, yet Coates’s keen storytelling compels the reader onward. Cowley’s observation about Yesterday’s Burdens is equally apropos of Wisteria Cottage — Coates once again lays his cards face up on the table, sure that he can pull the trick off in plain sight. He does so, brilliantly. Ultimately, the power of Wisteria Cottage is in how Richard Baurie is not so different from us: “He might be anyone, anywhere.”

That Wisteria Cottage’s saga of paranoia was first published in the post–World War II buildup to McCarthyism and blacklisting is no mere coincidence. In describing the suspicion and violence that captivate one man, Coates held up a mirror to the political paranoia and retribution that would bedevil America in the 1950s. Wisteria Cottage portrays the seduction of madness, and how it can turn us against even those we hold most dear. Valancourt Books’s reprint aptly coincides with a new American era of paranoia, demonizing the “other,” and impulsive violence in which repudiating factual reality is, to many, a badge of honor.

All three reissued novels have much to recommend them; each boasts an introduction by Coates scholar Roza, author of the excellent critical biography Following Strangers: The Life and Literary Works of Robert M. Coates. Robert M. Coates was so far ahead of his time that his inventiveness still dazzles. His Wisteria Cottage rings as true today as ever. Coates’s work deserves to be embraced as essential reading.

¤

Jack Mearns is a professor of psychology at California State University, Fullerton.

LARB Contributor

Jack Mearns is a professor of psychology at California State University, Fullerton. He was a Fulbright scholar at the University of Tokyo in Japan. He is the author of the nonfiction book John Sanford: An Annotated Bibliography (revised second edition, 2022, Cutting Edge Books) and the novels Deadline News — psychological suspense about obsession with celebrity — and Caliphornia, which turns the British colonial novel on its head.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Burden of History in John Sanford’s “Make My Bed in Hell” and “The Land that Touches Mine”

Jack Mearns explores the life and work of John Sanford, an oft-neglected 20th-century American writer who wrote incisive novels addressing American...

Tired of Living, Afraid of Dying: Horace McCoy’s Legacy

Horace McCoy’s depression lasted longer than the country’s.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!