Pain as Revolution: On Anne Boyer’s “The Undying”

Emily LaBarge reviews Anne Boyer's memoir/meditation on the personal and cultural experience of cancer.

By Emily LaBargeOctober 25, 2019

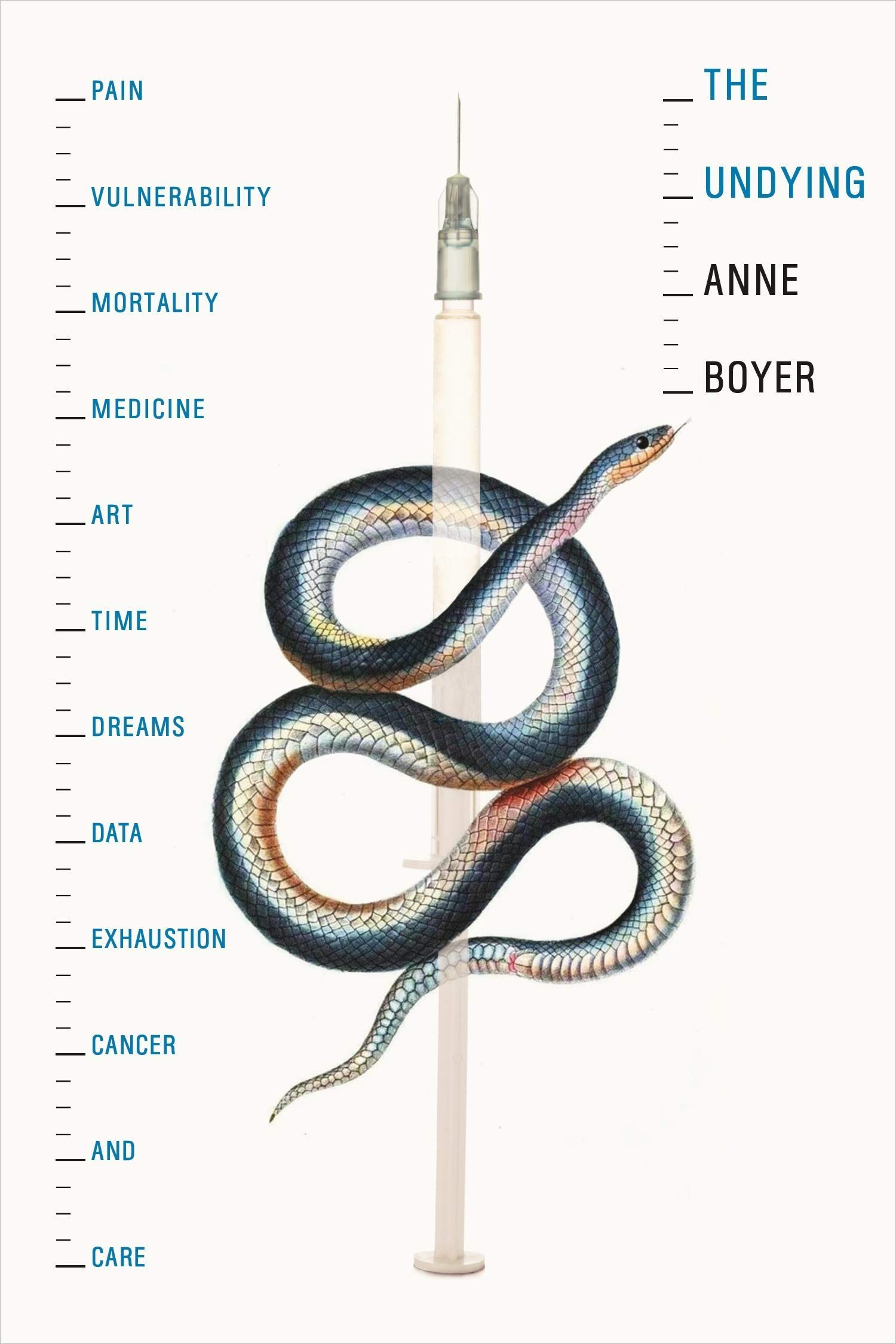

The Undying by Anne Boyer. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 320 pages.

TOWARD THE END OF poet and essayist Anne Boyer’s The Undying: Pain, Vulnerability, Mortality, Medicine, Art, Time, Dreams, Data, Exhaustion, Cancer, and Care, just before its epilogue, she writes, “I decide the question posed by this book is, Are you going to be the snake or are you going to be the snake’s cast off skin?” This question twisted in my mind and sent me back through the book looking for an answer, though I expected — if there were to be one — that it would necessarily be, both.

“I am confident,” Boyer writes, “that every person who has ever lived knows exactly what I mean when I describe feeling like a snake on the path in the dappled sunshine that turns out, on close inspection, only to be a snake’s discarded skin.” The snake regenerates, grows new skin, leaving its old self behind; it is forever in the process of becoming. Fresh scales shine and slither hopefully beneath — we endure, we continue. But Boyer’s subtle and shifting syntax says something else, too, and like The Undying as a whole, it resists neat platitudes, easy images, and formal closure. In the first half of her sentence, the subject feels like (is) the snake on the path; in the second half, the subjecthood of the subject — how she feels in the dappled sun, her knowledge that she exists — is instantly altered, by an omniscient, subject-less view, to become an empty husk, hollow and inanimate, but which still contains the living and lexical subject. The discarded skin still is, still feels: the discarded skin did not know that she was not alive, not real like the other snakes, until something pulled her out of herself to show her. A discarded skin knows who she once was and has an idea of who she might be. But now, she is here — and is there a choice, and what to do, and how to write it?

I’m beginning at the end, I know, but in The Undying there is no one story, one idea, one direction, one clause or cause, reason or remedy, message or moral. There is arguably not even just one person: Boyer, a 46-year-old woman with a highly aggressive form of breast cancer, is both narrator and voice (terms that are actively unsettled and remade throughout the book), and her writing is singular — as in exceptional, forceful, brilliant. But the overall project is collective. She writes:

Nothing I have written here is for the well and intact, and had it been, I never would have written it. Everyone who is not sick now has been sick once or will be sick soon. I dream in elaborately missed positions, of lakes and ladders I cannot climb, of a book with the title You Never Know and Probably Never Will. It has as its content the worth of each life.

The Undying, like cancer as Boyer takes us through it (hers and others’), is emphatically plural, a product of history, politics, social and economic relations. The book’s epic subtitle rejects its typical function, which is to narrow and define, to make specific. Instead, it multiplies and spreads to encompass all that is proximate: art, time, dreams, data, and more. Cancer is presented as one among many things, as a version or a symptom of everything — every desultory thing the world has to offer us, all intertwined and intricately bound, soaked through our bodies, some of which will suffer more and more visibly than others. Women, for instance; single women more so; single poor women, and single poor black women, most of all. Boyer refers to this apportionment of suffering as “the social morass of the disease,” which dictates that the worth of each life is relative. “The history of illness,” she writes, “is not the history of medicine — it’s the history of the world — and the history of having a body could well be the history of what is done to most of us in the interest of the few.” And, later, “It’s all made up. I mean having a body in the world is not to have a body in truth: it’s to have a body in history.”

The history Boyer takes particular aim at is 20th and 21st century, and Western — the history of industry and capital, carcinogenic manufacturing and big business; a history that is structurally racist, misogynist, classist, invested in profitable inequality, and blind to the suffering it produces. This history has produced our physical bodies and their illnesses, as well as the systems that order them, extract value from them, and ultimately treat them when they break down. Boyer describes being injected with Adriamycin, a drug known as “the red devil” and sometimes “the red death,” a ruby red liquid that “is known, if spilled, to melt the linoleum on a clinic floor,” and which is administered by a nurse clothed in elaborate protective garb. In Boyer’s treatment, Adriamycin, also known as doxorubicin, is combined with cyclophosphamide, a drug that has its origins in mustard gas, which was outlawed as a chemical weapon in 1925. “It is as if I am both sick with and treated by the twentieth century, its weapons and pesticides, its epic generalizations and its expensive festivals of death,” she writes. “Then, sick beyond sick from that century, I am made sick, again, from information — a sickness that is our century’s own.”

Cancer, Boyer observes, is the only disease whose treatment involves making a patient sicker: “It takes a wolf to catch a wolf,” one of the nurses tells her. But Boyer is neither of these fighting wolves, just the locus of the battle — a site where noxious and historically violent substances harm in order to heal, as they always allegedly have. The cost of living is high, literally: one shot of Neulasta, a white blood cell booster, is $7,000 (a patient typically needs three to four shots a year, but could require up to 10); and the price of one chemotherapy infusion is more money than Boyer has ever earned in any year of her life. Expectations of a patient’s life circumstances are equally steep: it is assumed that she has a partner or a parent to take care of her, health insurance, a job that affords paid sick leave (or any sick leave at all), a support network as robust as her income to help her rehabilitate physically, mentally, emotionally. None of this is spoken openly, but it is embedded in all the brochures, images, advice, guidance, and basic post-treatment requirements she receives — what is put forward as normal (and, therefore, presumably accessible) for breast cancer patients. It should go without saying, but certainly doesn’t within the US cancer care industry, that many American citizens may have one or two of these things, but few will have more, and almost none all.

In The Undying, history and its attendant illnesses are also linguistic, literary, narrative, formal. We are sick in our bodies, minds, words, cells, neurons, phonemes — a sickness that exists reflexively within the material world around us. “Breast cancer is a disease that presents itself as a disordering question of form,” Boyer writes, noting that issues of silence, censure, or shame, so present in cancer writing of the late 20th century (e.g., Susan Sontag, Audre Lorde, Kathy Acker, Rachel Carson — who never spoke publicly of her illness for fear that her research would be discredited by the US chemical companies she was investigating), have now been replaced by “the din of breast cancer’s extraordinary production of language.” “In our time,” she writes, “the challenge is not to speak into the silence, but to learn to form a resistance to the often obliterating noise.”

Boyer does not hear or see herself, or the realities of her world, in “Your Oncology Journey,” a binder filled with images of grateful and grinning bald women who reveal no pain; nor in “survivor” memoirs that emphasize heroism and the singular, triumphant voice; nor in the pink-ribbon stories of self-care and juice fasts and positive thinking and cosmetic tutorials and good-attitudes-will-be-rewarded blogs spun across the web; nor in literature and public readings in which sickness exists for the epiphanies of the well, and is always described as a matter of appearance — a sick woman’s fragility, her paleness, her vulnerable beauty. “None of this literature is bad,” Boyer writes, “but all of it is unforgivable.”

Such narratives inherently reproduce the world as it is, with its cruel inequalities, deflections of truth, misrepresented causalities, cynically reapportioned blame. They are the reification of the individual and her experience, which becomes a story with a legible narrative arc and familiar language — a product, an object to be sold and consumed, which then disperses and repeats itself, delimits and defines the contours of other products like it, even those that have yet to come into being. “I do not want to tell the story of cancer in the way I have been taught to tell it,” she writes, a mode in which “[w]omen’s suffering is generalized into literary opportunity.”

The common struggle gets pushed through the sieve of what forms we have to make its account, and before you know it, the wide and shared suffering of this world is narrowed and gossamer, as thin as silk and looking as special as the language it takes to tell it. […] The telling is always trying to slide down into a reinforcement of the conditions that made us want to say something in the first place, rather than their exposé, as if the gravity of our shared diminishments is more powerful than any ascendant rage.

The Undying is not the story of cancer as the dominant culture has taught us to tell or hear or imagine or understand it. It is anything but. In form, it is multiple, wayward, fragmented, rebellious, lucid, furious, beautiful, disorienting, unhappy, profound, painful, exquisite, precise, abstract, unfathomable. It ranges through space and time, its voice at times specific, at others dislocated and hovering; but always there is a careful awareness of overall structure, how each piece fits in, what repeats, echoes, expands. In content, it moves between descriptions of Boyer’s illness and ongoing treatment and the life that surrounds it — friends, ex-lovers, family, teaching, writing. There are meditations on, to name a few, John Donne and his Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions (1624), Bertolt Brecht, Diane di Prima, D. G. Compton’s The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe (1973) and its 1980 film adaptation, Death Watch, starring Harvey Keitel and Romy Schneider; close readings of Sontag, Lorde, Acker, and Fanny Burney on breast cancer, theirs and in general; the American health-care industry; cancer and aesthetics; culture and commodification; pain and language; illness and pretence; fear, loss, and spectral dreams.

Some passages float like prose poems, while others read as chapters, short essays, or disquisitions, sometimes instructions or imperatives — as in “communiqué from an exurban satellite clinic of a cancer pavilion named after a financier,” which instructs the reader how to weaponize her hair loss; or modern parables, as in “the first needle” and “the second needle,” which describe the impossible pain of chemotherapy and chest-expansion surgery — “impossible” because Boyer is told that the needles used don’t hurt, can’t hurt, technically, medically speaking, and she can’t really be feeling what she is. But they really do, and she really does. The Undying revolts and remakes formally, but also linguistically, syntactically. At turns Boyer’s language invokes Marxism and the Frankfurt School: enchantment, mystification, ideology, the real, the negative — grounding the work in a particular politics. This vocabulary exists alongside something stranger and more unsettling: patients at the cancer clinic are called “incubants”; when they see their insides projected on screens in light and dark, they are “imagelings”; in a dream, the living are “celebrants” — coinages that hang between the ancient and the futuristic.

Poetic repetition punctures description, illness and commerce commingle as Boyer reads about statistics and treatments on PubMed, wig reviews on online shopping sites. “I imagine a thousand fake things on me and a thousand other fake things in me and then a thousand fake things pending and then another thousand fake things forming and another thousand fake things in retreat.” Verbs skitter and eddy, take us through an experience that is at once personal and general, filled and emptied, emptying:

We fall ill, and our illness falls under the hard hand of science, falls onto slides under confident microscopes, falls into pretty lies, falls into pity and public relations, falls into new pages open on the browser and new books on the shelf. Then there is this body (my body) that has no feel for uncertainty, a life that breaks open under the alien terminology of oncology, then into the rift of that language, falls.

Taxonomies, lists, and hypothetical suppositions are a way into the linguistic world of pain, language reconstituted to its contours. One account is a list of unfinished aphorisms: “mutilated body as ecopoetic, unbearable pain as Kantian critique, dolor plastico,” and “every pietà a mastectomy scar, bionegated social unremittingest, etiological epithets,” and (in a nod to Emily Dickinson) “a formal feeling sums.” Another section, in which Boyer copies a passage from her notebook, shows what it means for language as one knows it to fall apart on the page, for syntax to be painful, 10 on the pain scale as “the panicking inadequacies of all genres, a new crisis of transmission”:

My pain’s naked grammar was:

how doe sone go on like htis the days gone finally in a way that can’t be though I have a light on my face to hceer me and I took an advicl will take more take vitamin d fake every sunlight the world on fire last night while I slept in such rgitheous pain.

While The Undying pointedly eschews modes of confession and sentimentality, I found this passage so bare that I could barely read it. Yet still I read it again and again for its plain, searing truth. In Boyer’s work, pain is not invisible or ineffable; it does not destroy language. We simply do not want to see or to hear pain’s realities — or, rather, we do not know what we are seeing or hearing, never having encountered it before within accepted modalities of expression.

Yet what if we had no choice at all but to confront, as Boyer describes Fanny Burney’s writing about her mastectomy without anaesthetic, “an account of that which we must witness but which we cannot allow our eyes to see, of that which we must understand but cannot stand to think about, and of that which we know we must write down but find unbearable to read”? What if there were something radically liberating in this experience? What if we were forced to grasp — through pain and illness, those sweeping levelers — the world as it might otherwise be or could have been? Boyer quotes Julien Teppe, founder of the pain-positive Dolorist movement, who wrote in 1935, “I consider extreme anguish, particularly that of somatic origin, as the perfect incitement for developing pure idealism.” She also quotes the German Socialist Patients’ Collective, who wrote in 1993, “Illness becomes the undeniable challenge to revolutionize everything — yes, everything! — for the first time really and in the right way.” She recounts the (failed) leper uprising of 1321, when lepers organized and planned to pollute water sources throughout France with “a mix of their urine and blood and four different herbs and a sanctified body,” which would render all the healthy sick; those who survived would emerge as natural leaders.

Boyer explores the possibility of pain as idealism, of pain as revolution, honesty, equality — not as something to aspire to or idealize, but as something that cuts to the quick and necessarily alters everything around you, everything inside of you, and demands a new form — a new world — that can meet it. As Boyer writes, “pain’s education should be in more than pain’s valorization,” and “we can’t think ourselves free, but that’s no reason not to get an education.” This is the space from which The Undying is written and from which perhaps it takes its name.

Boyer’s daughter tells her that she has done the impossible, she has “arranged for [herself] to write inside a living posthumousness.” Boyer notes her sense of writerly freedom: “After cancer, my writing felt given its full permission. […] It’s like the condition of lostness is, when it comes to being a person, finally what makes us real.” As one of the undying, having lived through a battered and disabling process in order to keep living, and now still missing parts of her former self, Boyer harnesses language and form to produce a body of writing that creates, embodies, and produces the effects of its own conditions — even when the form this takes on the page is a utopian book, the one she wants to exist, wants to write:

If this book had to exist, I wanted it to be a minor form of reparative magic, for it to expropriate the force of literature away from literature, manifest the communism of the unlovable, grant anyone who reads it the freedom that can come from being thoroughly reduced. I wanted our lost body parts to regenerate via its sentences and for its ideas to have an elegance that will unextenuate our cells.

Toward the end of The Undying, after the snake and its husk on the dappled path, but chronologically sometime earlier in the story (if we can call it that), Boyer thinks about all the writers who died early and whom she wishes had lived: Mary Wollstonecraft, Flora Tristan, Margaret Fuller — “sororal deaths,” or “women dying of being women,” as Boyer puts it in the book’s prologue. “Before I got sick,” Boyer writes, “the work of these dead women had kept me company. They had imagined a new structure to the world and with it, the world’s real responsibilities.” May they continue to do so. And may we add to this list the women who likewise continue to write and live and imagine in the same vein, beginning, but not ending, with Anne Boyer and The Undying.

¤

Emily LaBarge is a Canadian writer living in London, where she teaches at the Royal College of Art.

LARB Contributor

Emily LaBarge is a Canadian writer living in London, where she teaches at the Royal College of Art.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Enduring Appeal of Cancer Lit

Two new cancer memoirs expand a growing canon.

Not Unpacking but Seeking

A collection of essays on gender, the body, resistance, and the Occupy Movement.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!