Oncology’s Darwinian Dilemma

A young doctor ponders oncology’s latest dilemma: uncertainty rooted in variation.

By Bobak ParangMay 11, 2022

“NO CANCER PATIENT should die without trying immunotherapy” is a refrain in oncology clinics across the country right now. A treatment consisting of antibodies that awaken the immune system to attack cancer, immunotherapy carries far more promise than chemotherapy, and it has considerably fewer side effects. Since the FDA’s first approval a decade ago, it has revolutionized cancer care. Consider Stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. Twenty years ago, when the only option was chemotherapy, oncologists could tell their patient, with almost 100 percent certainty, that they would not be alive in two years. Today, miraculously, many patients with Stage IV lung cancer are alive five years after diagnosis — and some are even cured.

But the rub is that this immunotherapy revolution applies only to a narrow set of patients. Some benefit, but the majority do not. And patients who are cured constitute an even smaller minority. Why is this? How can immunotherapy cure a 65-year-old, newly retired man of Stage IV lung cancer, restoring the promise of his golden years with his family, but do nothing for the 55-year-old woman whose cancer robs her of decades of life? We do not know. A flurry of research is aimed at trying to answer this question. And what it is uncovering is the sheer variety of lung cancer and lung cancer patients. No two patients with lung cancer are the same. Their tumors have different genetic mutations. Their immune systems behave differently. We are even learning that their metabolisms can affect responses to treatment. And, astonishingly, emerging evidence suggests that the billions of bacteria that colonize their skin, lungs, and colons play a role in how they respond to cancer treatment.

That each patient with cancer is unique is not surprising, nor is it a new insight. It is, after all, fundamentally Darwinian. Indeed, one of Charles Darwin’s most profound observations in 1859 was that the defining reality of nature — of life — is variation. Our tendency to organize nature, Darwin argued, into delineated categories, such as classifying a set of animals into a species, is a strategy of convenience that is necessary but costly. Instead of emphasizing variation as the rule, we dismiss it as the exception. “No one supposes that all individuals of the same species are cast in the same actual mold,” Darwin wrote. Wherever you look in nature, you will find that any species is a collection of individuals with “indefinite variability in the endless slight peculiarities,” not a set of identical organisms. Darwin built his case for the primacy of variation on a bedrock of meticulous observations on species ranging from pigs to peacocks. (It was this variation, he would go on to say, that fuels natural selection.) By establishing variation as the rule and not the aberration, he dismantled the Platonic view that there are ideals — or expected versions or molds — of species. He released us from a worldview that narrowly focuses on conformity — and revealed to us one of nature’s great laws that quietly and forcefully powers our world.

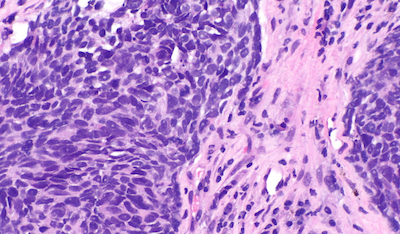

Today, we see the proof of that variation at depths and breadths unimaginable to Darwin. He saw rich variation in the colors of pigeon feathers; we see breathtaking variation in the sequences of genomes. Darwin was dazzled by the spectacular varieties of blue, red, and yellow hyacinths; we are perplexed by the multitudes of the immune system. Cancer, too, we are finding, is proof of nature’s profound variation. In the last five years, we have developed technologies to break apart tumors into single cells and analyze the DNA, RNA, and protein of individual cancer cells. Even at this level, we are finding a bewildering richness and complexity of variation. Variation scales across life: genome to genome, cell to cell, tumor to tumor, and person to person.

So why do we often still view the average prognosis of a population as an expected prognosis of an individual? Perhaps we are still shaking off our residual Platonic tendencies. Twenty years ago, the instruments we used to treat cancer were blunt enough that the variation of nature did not matter much. Chemotherapy, by and large, has a predictable outcome. Now, however, equipped with a wider array of sophisticated tools, we are unmasking the spectrum of variation and finding that results can be dramatic and unpredictable. Immunotherapy demonstrates this best: our treatment responses can range from a cure to no effect for the same “type” — or species — of lung cancer. Add other classes of drugs, like targeted therapies and those in clinical trials, and we expose more and more of the variation inherent in cancer.

The fundamental truth that Darwin uncovered 150 years ago has led to the oncologist’s dilemma, captured by the expression “no cancer patient should die without trying immunotherapy.” If you accept that variation is the rule and you reach a point when a patient’s cancer is growing despite our best available treatments, why not, as a doctor, try something? Whereas a few years ago there were few alternatives, now there are countless new drugs, each carrying its own range of uncertainty. We may not know if the new drug works or we may have some evidence that, on average, the drug may not work for this patient’s cancer, but we do know that variation is the essence of nature. And if there is a five percent chance the patient’s cancer shrinks and gives a family more quality time with their father or mother, is it not worth a try? What if there is a one percent chance the patient could be cured?

The pushback here is Hippocratic. The physician’s oath of “do no harm” fills the vacuum of uncertainty, and appropriately so. No drug, after all, even immunotherapy, comes with zero risk of harm. In clinical trials, most drugs have little if any benefit, unfortunately. And giving a drug that makes a dying patient suffer is to risk bringing about what Emily Dickinson described as the “Languor of the life / More imminent than pain / ’Tis pain’s successor / When the soul has suffered all it can.” Variation may be liberating: it can provide hope to patients and families. But that hope could very well be purchased at the cost of undue suffering: the same uncertainty that carries the promise of a cure carries the possibility of suffering.

How to resolve this tension is one of the most challenging tasks facing modern oncology. A growing number of oncologists are enlisting the services of their palliative care colleagues. Historically, palliative care was a discipline of medicine that dealt with end-of-life care and helped patients transition to hospice. But over the last decade, palliative care has transformed into a dynamic field consisting of doctors, nurses, nurse practitioners, and social workers whose goal is to enhance the quality of life of a cancer patient throughout their life, not just in the final moments. Experts in the management of symptoms like pain and nausea, they also assist with making decisions about whether to pursue a new treatment or a clinical trial. Their approach to wrestling with uncertainty is to define, concretely, each patient’s personal goals in life. By fixing one variable firmly, the hope is that the remaining uncertainty narrows.

A few years ago, I met a woman in her 70s. An immigrant from a country halfway across the world, she had lived in New York for 50 years. She was independent, active, and lived a few blocks away from her children and grandchildren. A few weeks before I met her, she experienced worsening pain in her right side. She went to her primary care doctor, where blood work showed elevated liver enzymes. Soon after, a CT scan showed she had multiple masses in her liver, lungs, and bones. A biopsy revealed the diagnosis: Stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. When we met her, her goals were clear: she wanted to live as long and pain-free as possible in order to enjoy her time with her children and grandchildren. We started her on a combination of chemotherapy and immunotherapy, and within several weeks, her cancer began to shrink. She felt better and stronger.

A few months later, however, the pain returned. A CT scan confirmed our suspicion that the cancer was growing again. We changed her treatment to another chemotherapy drug combined with one designed to choke off the tumor’s blood supply. The cancer was held at bay for a few months, but soon after, her tumors once again grew and expanded. What to do next? We discussed two options: 1) we could switch to another chemotherapy, which we thought might at best stop the cancer from growing for a short period of time, or 2) have her enter a clinical trial involving immunotherapy. Whether the trial would work, we did not know: the data was limited. And then, over several phone calls and office visits with the patient, her family, and our palliative care colleagues, it became clear that the patient’s goals had changed. More than anything, she wanted to return home to her native country. The chance of extending her life was not as important as the guarantee of seeing her home country once more. She was in good enough health to make the trip. She said goodbye to her children and grandchildren, knowing she would not see them again. She made the trip back home and died a few months later.

Even when a patient’s goals are clear, the uncertainty remains. Would the trial have extended her life, giving her more time with her family? Or would it have brought about suffering? I do not know, but I think about it.

The larger hope is that as research marches on, we will be able to predict, with high certainty, whether patients will respond to treatments. Variance will shrink as our knowledge grows. But this thinking, too, would benefit from revisiting Darwin’s observations. Nature is not static. Our environments are dynamic and ever-changing. Cases in point: the alarming rise in the number of young people diagnosed with colon cancer, and with lung cancer, too. Variation, like gravity, is a fixed law of nature — and so our predictions are always qualified by probabilities and contingencies.

In On the Origin of Species, Darwin wrote that “I look at individual differences, though of small interest to the systematist, as of the highest importance for us.” The same applies to modern oncology today. We are rapidly moving cancer care forward through valuable clinical trials that study large populations, but after the trials, we must do the work of applying those lessons to the singular patient before us. Our new dilemma — uncertainty rooted in variation — is fundamentally a blessing, a direct result of our breakthroughs: the certainty of futility is now replaced by the uncertainty of possibility. And as we further advance research, we will capture ever more of the “indefinite variability in the endless slight peculiarities” noted by Darwin. Some of these “slight peculiarities” will lead to dead ends, but others will open new vistas full of potential treatments, dramatically improving the lives of patients. Never has there been a better time to be a cancer patient — or an oncologist for that matter. At least this is something we can be certain about.

¤

Bobak Parang is an oncology fellow at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York.

LARB Contributor

Bobak Parang is an oncology fellow at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Doctor’s Dissent

A doctor attacks those maverick doctors who lambaste the medical profession while channeling its hubris.

Evolution Wars: The Saga Continues

Jessica Riskin offers a revisionist history of evolutionary biology.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!