On “Wanda” as Carrier-Bag Feminist Film

Adèle Cassigneul compares two recent monographs on the landmark feminist film “Wanda” (1970).

By Adèle CassigneulJanuary 26, 2022

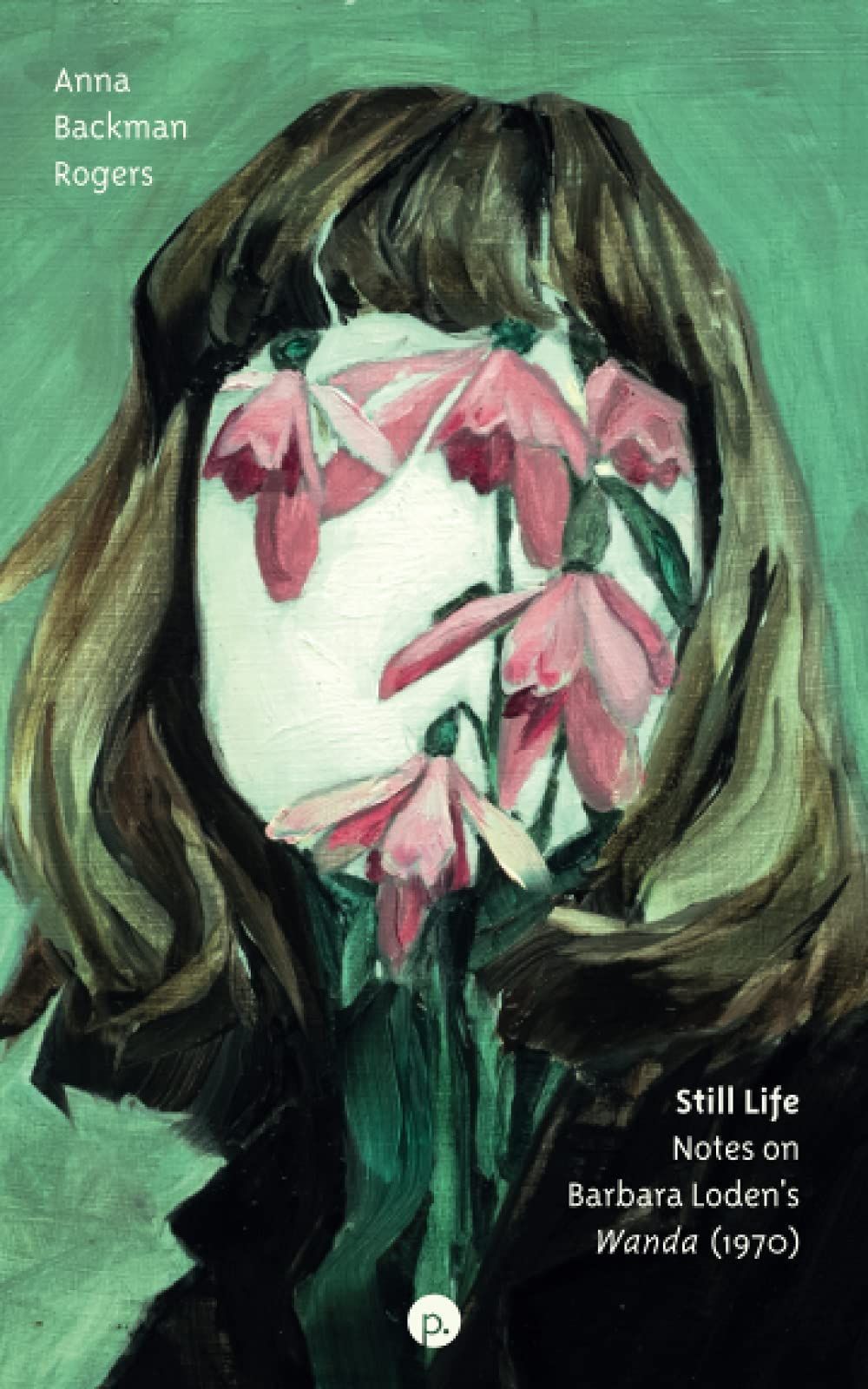

Still Life: Notes on Barbara Loden’s Wanda (1970) by Anna Backman Rogers. Punctum Books. 154 pages.

Suite for Barbara Loden by Nathalie Léger. 128 pages.

SEPTEMBER 23, 1959: Alma Malone and her partner in crime, Mister Ansley, kidnap Mr. Fox, a bank manager, and fail at robbing a bank. Ansley is shot dead and Malone, who was supposed to follow Ansley but took a wrong turn, vanishes. The police catch her three weeks later. When sentenced to 20 years of prison and sent to the Ohio Reformatory for Women in Marysville, she thanked the judge. “I’m glad it’s all over.” Alma Malone entered the prison on January 21, 1960, prisoner number 7988, and was freed on parole on April 8, 1970. Then she disappeared.

As a working-class woman herself, actress and director Barbara Loden was touched when she read of Malone’s story. And as an artist, she was intrigued. It took her almost a decade to make a film out of this fait divers: Wanda, which won the Best Foreign Film Award at the Venice Film Festival in August 1970 and was barely shown in the United States or elsewhere in the spring of 1971. Loden explained how deeply this story affected her: Who would desire to be put away? What kind of woman would regard imprisonment as a welcome respite from the burden of her daily life? Alma Malone probably never knew that, through Loden, she had become Wanda.

After writing, shooting, and playing Wanda, Loden never had time to make another film. Her project of adapting Kate Chopin’s The Awakening never materialized. She died of breast cancer on September 5, 1980. Wrapped in a pale halo of grief and mystery, the film carries the ghost narratives of many wronged, silenced, and erased women.

Wanda came to the world silently, almost imperceptibly, because it wasn’t seen, wasn’t heard. It discreetly vanished too. Like Alma, like Barbara. Over the years, it has been lost and rediscovered, dismissed and acclaimed, neglected and upheld as a feminist cult classic. In spite of it all, Wanda has miraculously survived. And it has a lot to tell us. As Anna Backman Rogers puts it in her latest essay, Still Life: Notes on Barbara Loden’s Wanda (1970), published by Punctum Books this summer:

This film, made by a woman who knew all-too-well what it means to be defined through and by her material circumstances (and her relationships to men), that is so relentlessly ferocious in its refusal to assuage and comfort the viewer was always a film […] that was made for the future.

Today, we owe Wanda to a community of women who salvaged it from oblivion: critics and academics who kept its memory alive and created an important body of scholarship; authors, like Nathalie Léger and Kate Zambreno, who identified with Loden/Wanda and wrote about it; and actress Isabelle Huppert, who financed and oversaw the rerelease of the film in 2003. Loden’s film has left lasting marks on those few who have seen it.

Inspired by Malone’s story without being identical to it, Wanda follows an unemployed, penniless woman who has left her husband and two kids but who otherwise “lacks the perspicacity, means, and energy to alter her life.” Rogers skillfully shows how Loden’s film confronts “harsh and brutal truths” that “reveal the implication of the psychic in the social and the experiential in political structures.” She also aptly argues for a feminist reading of Wanda that does not glamorize her distress (as many have done for Marilyn Monroe, Virginia Woolf, and Sylvia Plath) or erect a tragic monument to her sad destiny.

Some, like novelist Annie Ernaux, confess they need films like Loden’s to form story lines inside them when they feel neglected and forsaken. In Ernaux’s masterpiece The Years (2008), the narrator looks for her own life in Wanda’s life. She asks the film to give her a future or an understanding of her own feelings and experiences — of her loneliness, her helplessness, her hopelessness. Identifying with Wanda helps her understand the whys, the hows, and the where-tos. Ernaux says that, at the time of her divorce, when she was writing A Frozen Woman (1987), she was “in search of [her] own path as a woman, [her] own reality as a woman.” And Wanda pointed a direction.

Others, like Nathalie Léger, prefer fantasizing Loden’s Wanda, hollowing her out as they transform her into a pathetic myth. They build fictive worlds around Loden’s character, weaving webs of essentializing associations that vampirize her and cast her as the brainless victim, a pale scatterbrain version of Loden herself.: “I try to see beneath Wanda’s lost expression, beyond her forlorn face and the nervous, distracted way she holds herself in front of other people. I’m trying to find everything that she has in common with Barbara.”

For Léger, as it was for Marguerite Duras before her, “there is an immediate and definite coincidence between Barbara Loden and Wanda.” In Léger’s autofictitious reading-writing of the film, Loden disappears into Wanda and Wanda-who-is-Barbara becomes Miss None, an empty, see-through creature, an insubstantial zombie who is used as a container for Léger’s personal search.

Reading Suite for Barbara Loden, I learn more about Léger than about Loden’s Wanda. I can’t help wondering if is this one of the limits of autofictive writing, when the author uses an artist and her work as a mere pretext for her own introspective inquiry. Is autofiction, in many ways a “feminist practice,” bound to subsume a character’s complexity to the complexity of the author’s own life, turning life-writing into a solipsistic venture rather than a collective one? Words from Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own echo: “[M]asterpieces are not single and solitary births; they are the outcome of many years of thinking in common, of thinking by the body of the people, so that the experience of the mass is behind the single voice.”

When Léger’s text came out in 2012, Marie-Laure Delorme wrote in the Journal du Dimanche of Léger’s interest in “enigmatic women, secret women who have no secrets, women condemned to desolation. Opaque beings.” This description reminded me of another work from Virginia Woolf, her 1929 story “The Lady in the Looking-Glass: A Reflection.” The story starts when Isabella has gone into the garden and vanished, leaving the voyeuristic narrator with an empty mirror to gaze at. Who is Isabella? What does she think or dream of? What does she want? What does she do next? Woolf’s stubborn narrator symbolically assaults her character, using it as a vessel for her own fantasies. One must fasten her down here, fix one’s mind upon her, pry her open with the first tool that comes to hand — the imagination, she says. Isabella becomes a recipient for the narrator’s stories and analogies. And when she comes back from the flowery garden, “lingering and pausing,” and finally stands perfectly still in the mirror, lighted by a pitiless halo, everything drops from her: “[T]here was nothing. Isabella was perfectly empty.” Friendless, old, and angular, she remains voiceless and motionless, brutally abandoned and blatantly unloved.

Léger chronicles her research on both Loden and her film, and, as she does, tries to pin them down, to crack them open. Her fascination is eminently intimate, at times nosy and fetishistically morbid (as her text on the Countess of Castiglione, Exposition, also is):

I can’t tell him [Loden’s son] that I am desperate to find Barbara Loden’s journal. I can’t tell him that what would interest me in the journal — if it even exists — is not joy, enthusiasm, happiness or fulfillment, but grievance, powerlessness, strange lists, scorned emotions. What secret, other than that of failure, what else do we feel we must hide as carefully as we hide our disappointment?

Léger never really considers Wanda’s — or Loden’s — irreducible singularities, never questions the representation of feminine emptiness or alienation, their political dimension. She only talks about the sadness she herself projects onto Loden’s life and her movie. She desperately needs Wanda-who-is-Barbara to reflect on her own life and, turning her into an insubstantial being, she makes her opaque. Under her pen, Wanda appears as an autofictitious vision of Loden, a mere mirror image of Léger’s own literary project. She doesn’t know that, as Woolf shows it, to approach Wanda and really understand her experience and symbolical importance as a character, one must first give her back to herself.

In Still Life, Anna Backman Rogers pushes back against that kind of obsessive and sentimental reading to offer an invigorating reviewing of Loden’s film. When Léger seems only interested in the psyche and interiority she seeks to decipher, Rogers holds on to a meticulous analysis of Loden’s radical cinematographic gesture. Instead of embarking on an exploratory ego-trip (Léger actually writes of her travels to America as she researches her book), she sets to efficiently give Wanda back to her author, and to return her political agency. Having co-founded the online journal MAI: Feminism & Visual Culture (where I am a member of the editorial board), Rogers knows that writing on a woman’s life and work entails critical ethics or, as sociologist Éléonore Lépinard puts it, a feminist ethics of responsibility.

Why idealize and essentialize abandonment, dejection, or desertion — complex states of being that the world makes us be? Loden pictures a woman that does not have the means — financial or emotional — to fight for herself because she is enduring her condition as an outcast day after day. As Rogers argues, her depression and melancholia are socially produced, they are a “public feeling,” the product of a capitalist patriarchal society. How then can her reluctance, muteness, and hesitations be anything other than “a protective process of retreat from the world”? Wanda has difficulties speaking for herself because she has nothing to anchor her in the world and because she has lost all access to her own sense of individuality.

“Wanda is a woman who has been forced to become anaesthetised to her condition in order merely to survive,” asserts Rogers. And the film, in its aesthetic construction, centers on liminal places (motels, cafés, malls, a bus, a car) that barely frame its character. A ghostly outsider, Wanda haunts the margins of the image as “a decentred, displaced, and nebulous adumbration of a person.” This, Rogers contends, is deeply political. It is deeply feminist. Antiheroic too.

I think of Ursula K. Le Guin’s words in her 1986 essay, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction”: “That’s right, they said. What you are is a woman. Possibly not human at all, certainly defective. Now be quiet while we go on telling the Story of the Ascent of Man the Hero.”

Still Life presents Loden as a professional — a performer and a director — and Rogers pays attention to what she did to the fictional world she created, putting it back in its historical and critical contexts. With Wanda, Loden thwarted all the standard scripts and all the clichés about femininity, deliberately making an anti-Hollywood movie. Her film is a subtle site of feminist contestation and critique, an anti-capitalist reflection on refusal, failure, and loss:

That failure is personalised, so that blame lies not with the body politic and corporations, but with the individual who has proven unable to accede to and maintain the strict mores of the capitalist model (made evident as the practice of being a ‘good’ citizen), is precisely what Loden sets out to critique biopolitically in her film.

Rogers reminds us that Wanda was made for the future, that it talks to our contemporary moment, and she tells of what it will do if only we, as reader-viewers, pay attention. Loving attention. Loden’s Wanda urges us to respond, to react, to willfully gaze at the unendurable realities of our world — at Wanda’s obliteration and her silent survival. This is a call to “uphold core feminist values of solidarity, compassion & agency,” as Rogers and Anna Misiak put it in the manifesto of MAI: Feminism & Visual Culture, which they co-created in 2018. “We believe that the future can be better & it starts with us learning to listen to one another. We think that feminist art & stuff makes the world a far better place — yes, we do!”

Still Life is a concerned and visceral essay that believes in the heuristic function of art. Through her scrupulous scrutiny, Rogers acknowledges the ethical responsibility of each of her critical acts. Brimming with both tenderness and rage, she offers a remarkable text which reflects on Loden’s radical portrait of a woman disintegrating before our eyes. Her study branches out from her previous work on American independent cinema and reworks her concept of the crisis-image that centers on “tropes of depletion and exhaustion with American values (especially Christianity and capitalism).” She engages with debates on film genre, arguing in favor of Loden’s counter-cinema as a political gesture that confronts the Hollywood institution: its hegemonic filmmaking and reproduction of a patriarchal, capitalist ideology. Exploring “the difficulty or impossibility of progression through extended moments of liminality and threshold,” this cinema of crisis is exemplified by Wanda’s focus on stasis, impasse, slowness, repetition, margin, and exile — something Rogers sees at work in Kelly Reichardt’s films too.

In “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” Le Guin disputes those heroic modes of storytelling, modes particularly celebrated by classic Hollywood cinema such as Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969) or Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967), to which Wanda has often been compared. She writes in favor of the other stories, the neglected ones, the life stories. Le Guin conceives of fiction as a carrier bag, as “a medicine bundle, holding things in a particular, powerful relation to one another and to us.” These fictional bags are, she says, “full of beginnings without ends, of initiations, of losses, of transformations and translations, and far more tricks than conflicts, far fewer triumphs than snares and delusions.”

Carrier-bag fictions offer neither resolution nor stability but continuing process, sheer becoming. There are no heroes in them, only people. (Loden employed many non-actors to play alongside Michael Higgins and herself, who were both accomplished performers.)

Wanda is a carrier-bag film that reflects on how its female protagonist is used as a container by other people, especially men. She is a woman who cannot narrate her own life and struggles to barely survive, a woman who cannot stand for herself as an individual because she does not recognize or articulate her own desires and needs. How do you tell the gap-filled story of a precarious life? Maybe you don’t need to tell but rather show it and, through image, share its trying yet banal experience. You make it grainily obvious and tangible. Unavoidable.

On the book’s cover figures one of Hélène Delmaire’s flower faces. It’s an uncannily beautiful image that portrays a woman colonized by bunches of rosy blooms. Her neck is made of thick green stalks. You can feel their solid density. Her eyes are but pending petal bells. She has become a host for something not herself. The image also evokes Wanda’s handbag, another container which, throughout the film, gets emptied of all its scanty contents. Her rollers, purse, and personal photographs get stolen and thrown in the bin or out of the car window before she even realizes her stuff has been taken. This symbolizes Wanda’s story of dispossession and tells of an entire feminine history, a history of appropriation and rape. It might not be a coincidence that Wanda uses her empty bag to fight off the military man who assaults her toward the end of the film.

Wanda’s carrier bag holds Loden’s fictionalization of Alma Malone’s story. It holds the story of many abducted ancestresses in the past. Wanda never lets go of it as it carries her own purposeless story, the bleak chronicle of her ineluctable drift. It is a testimony of both her struggles and her desperate resilience.

When I first read Rogers’s essay, the pace of her astute and energetic prose took me aback. Her sentences are swift and efficient, uncompromising. After establishing some key concepts with care and precision and stating her critical standpoint, she embarks on an edifying shot-by-shot reading of the film, interspersed with her own affective response to the scenes. Hers is a highly rigorous and uniquely personal take on Wanda, one that is at once humble, collective, and generous. Rogers has invented her own carrier-bag version of film criticism, highly engaged and reparative. It never uses the language of power, never brags or lectures. It does not speak from above but from within Loden’s film.

¤

LARB Contributor

Adèle Cassigneul is a French independent researcher and critic who specializes in modernist literature, visual cultures, and gender studies.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Humiliation of No Longer Being Desired: Nathalie Léger’s Investigations of Abandonment

Nathan Scott McNamara considers Nathalie Léger's "The White Dress," out now from Dorothy in a translation by Natasha Lehrer.

In the Margins: A Conversation with Kate Zambreno

Sara Black McCulloch speaks to Kate Zambreno, author of “Screen Tests,” a collection of stories and other writing.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!