On Being Off: The Case of Amanda Knox

There are, by now, several accounts of Amanda Knox’s story.

By Tom DibbleeAugust 12, 2013

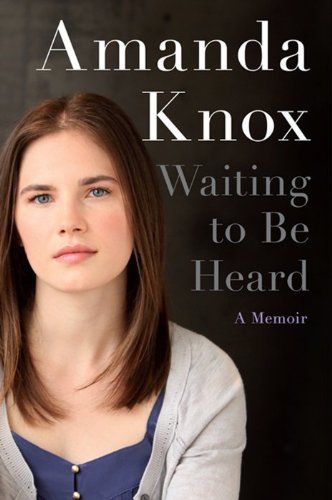

Waiting To Be Heard: A Memoir by Amanda Knox. Harper. 480 pages.

ON THE NIGHT OF NOVEMBER 1, 2007 in Perugia, Italy, somebody stabbed the 21-year-old British student Meredith Kercher in the neck. Her body was found in her bedroom half-naked and under a duvet; there were skin cells inside her vagina but not semen or blood, and there wasn’t enough bruising on her labia or thighs to conclude that she’d been raped. Five days after the murder, the police arrested Amanda Knox, Kercher’s American roommate who, like Kercher, was in Italy to study abroad. The police had questioned Knox three times before, as a witness, but on her fourth meeting with investigators, the tone shifted. Knox was held at length, without a lawyer, and claims she was slapped and berated into describing what might have happened to her roommate. Eventually, Knox described a possible scenario in which she left her boyfriend Raffaele Sollecito’s apartment, where she originally said she’d been sleeping, and witnessed the crime. The police wrote a statement for her in Italian, which she signed. Later, Knox would qualify her statement by calling the scene her statement described a “vision.”

The prosecution’s theory of what happened evolved over the course of 2008, but they finally accused Knox, her boyfriend Raffaele Sollecito, and an acquaintance named Rudy Guede of trying to force group sex on Kercher as a form of revenge for her “too-serious” ways, and of killing her when she resisted. In his closing argument, the prosecutor, Giuliano Mignini, sketched a scene in which Sollecito held Kercher’s arms and Knox delivered the fatal blow while Guede fingered Kercher’s vagina from behind. Satanic and Masonic rites at various times featured into this plotline, and the fact that no hard evidence tied either Knox or Sollecito to the crime scene only encouraged these suppositions; Mignini believed that for Knox and Sollecito to vanish without a trace, they would’ve needed the help of a mysterious conspiracy of evil.

After a year of detention, Amanda Knox, Raffaele Sollecito, and Rudy Guede were convicted to serve 26, 25, and 30 years, respectively. Three years later, an appeals judge found that “proof of guilt” did not in fact exist for Knox and Sollecito, and let them go. Knox went home to Seattle and wrote a memoir about her ordeal. Then, in 2013, Italy’s Court of Cassation ordered a retrial for Knox and Sollecito. The Court filed its “motivation,” saying it was judging not the original testimony but the process by which the appeals court overturned the original conviction, though its statement also indicated that the court supported the prosecution’s original theory about an erotic game gone terribly wrong.

The guy whose bloody fingerprints and DNA are all over the crime scene, who fled to Germany in the days after the crime, and whose testimony continues to evolve but always confirms his presence the night of Kercher’s murder, is Rudy Guede. In his first testimonial, a recorded Skype conversation made before his arrest, Guede admitted to being in Knox and Kercher’s apartment at the time of the murder, but said he was in the bathroom when he heard screams from the young woman’s bedroom and rushed to try to save her. Upon his arrest in Germany, he said that Knox and Sollecito were not involved. Once in the custody of the Italians, he claimed that Knox and Sollecito were, in fact, present at the crime scene, and his sentence, on appeal, was reduced from 30 years to 16. Later, a few of Guede’s fellow inmates would come forward to say that Guede had told them that, actually, Knox and Sollecito weren’t in the house after all.

¤

In the summer of 2011, as Knox was appealing the original decision, I was at work on a novel about a guy who fantasized about going to prison. Prison, he thought, would be an upgrade from the boring doldrums of his day-to-day. Behind bars he’d at least be able to read and write as much as he wanted, and he wouldn’t have to bother with the clumsy reality of pursuing the out-of-reach girl he was obsessed with. Prison was just the place for his ineffectual self, though he didn’t foresee that in committing the crime required of him to get there, he would come alive in a whole new way.

In June of that summer, Nathaniel Rich published a piece on the Knox case in Rolling Stone. In reading it, I learned two things. The first was that Knox was definitely innocent. Rich detailed how the postal police, who deal with Internet crimes like frauds and scams but also pedophilia, happened to arrive on the scene before the carabinieri, the Italian military police force that sometimes assists with crimes like murder. The postal police tramped through the house led by “a band of child sleuths out of Scooby-Doo” comprised of Knox, Sollecito, and the Italian girls Knox and Kercher were living with, disrupting the scene and tampering with evidence. But evidence mattered little to the prosecution, anyway, who instead focused on Knox’s inappropriate behavior immediately following Kercher’s death — kissing Sollecito at the house while the police investigated inside and cuddling with him later at the police station, among other things — and their assessment that she had no sadness in her eyes.

The other thing I learned from Rich is that, behind bars, Knox was spending her time reading authors like Nietzsche and Borges and Kafka. Knox, an aspiring writer, was doing exactly what I imagined my protagonist doing. And also, in her letters home, she expressed basic desires — like wanting to be a mom — that, by being written from prison, had a resonance that these desires don’t have when expressed by a free person. This, too, was something my naïve aspiring-writer protagonist wanted from prison: resonance for his basic hopes and fears.

None of the hard evidence the prosecution presented to tie Knox and Sollecito to the crime scene survived the appeals trial.[1] The real reasons they remained suspects were psychological: the prosecution pursued Knox based on their belief that she was inherently bad, and Sollecito based on their belief that he was her smitten lackey. They believed that behind Knox’s cold, unfeeling eyes lurked a soul given over to the will of the devil. Mignini, his assisting prosecutor Manuela Comodi, and the police felt as if they could see inside her, and their conviction about what they saw overruled a lack of evidence they dismissed as a low-level inconvenience, the earthly interference in a case built around the nature of Knox’s soul.

This, to me, is a worst-nightmare scenario: being judged a monster on the basis of a failure to act correctly. There are times when my social graces abandon me, when I act in various “off” ways: becoming bored and remote at the bar, to the annoyance of my friends; turning inexplicably cold toward girls I’d pursued full throttle the night before. In the aftermath of these spells of offness, I imagine that everyone knows what my behavior reflects: true and terrible internal corruption.

After her roommate died, Knox didn’t cry enough for the Italians. Instead, she looked dazed and shell-shocked. At the police station, after sitting for hours, she did yoga on the floor, having no idea that she was becoming a suspect. There in the police station waiting room, she felt totally protected and safe and free to be who she was; she was innocent, and everybody would have to recognize that: Knox believed that the people around her could see the innocence inside her. But the cops who were under pressure to solve a high-profile case hated her for her quirks, for her yoga, for cuddling with Raffaele when she should’ve been sitting in that waiting room red-eyed, submissive, and solemn.

When Knox did show emotion, she did so in the wrong sorts of ways. In the waiting room, while Kercher’s British friends wondered through tears about whether or not Kercher had died quickly, Knox blurted, “What the fuck do you think? She had her throat cut.” And, on her way to be fingerprinted, she began hitting herself in the forehead over and over. The police officer who was with her asked if something was wrong, and Mignini would go on to conclude that Knox was trying to knock away the memory of her role in the murder.

Knox’s behavior upon returning home the morning after the crime didn’t make sense to the cops either. She’d slept at Sollecito’s, but she went home to 7 Via della Pergola to take a shower and get a mop to clean up the puddle that had formed on the floor under Sollecito’s leaky kitchen sink. When she got home, she found the door ajar, a few blood spots on the sink in the bathroom, Kercher’s bedroom door locked, and an unflushed toilet full of feces in the second bathroom. But she didn’t call the police. Their door had never locked very well, and she thought the blood must have come from her own recently pierced ears or Kercher’s menstrual bleeding. She did, when she got back to Sollecito’s, describe the situation and ask him to return with her to the house to investigate. But when she detailed this course of events to the police and her roommates, they couldn’t understand why she hadn’t called the police immediately.

On the morning of November 2, soon after the postal police broke down Kercher’s bedroom door and discovered her body, the press installed themselves outside 7 Via della Pergola — which would come to be known as the “house of horrors” — and caught video of Knox and Sollecito standing apart from the rest of the crowd. In the video, Knox and Sollecito are holding each other, casting worried glances, and exchanging quick kisses. When I watch this now, I think they look nervous and scared. Sollecito seems to be consoling his distraught girlfriend. To me, they look traumatized because somebody just brutally murdered Meredith Kercher, and because the world they were living in, a world in which people they know don’t get stabbed in the throat, has evaporated and given way to a far more terrifying world. The skin cells inside Kercher’s vagina were Guede’s; in one of his various conflicting accounts of the night, he masturbates over her body after she’s been stabbed.

But in the context of the unfolding investigation, with Knox and Sollecito sans alibi (they were at Sollecito’s apartment, with only each other to verify their whereabouts), with Knox telling a story of an open front door and blood in the bathroom that didn’t seem to add up, with Knox looking remote rather than sad and swiveling her hips and saying “tah-dah” after donning paper booties to tour the downstairs apartment, with the police arriving at 7 Via della Pergola to find Knox outside with a mop as if she’d cleaned up after the murder (the mop had no signs of Kercher’s DNA), the video seemed to mean something totally different. It made it seem like they were afraid of their guilt being discovered rather than of the new world that confronted them, in which murder happens to people they know, in their own homes.

Knox didn’t call the police when she got home from Sollecito’s because she was naïve. She was incapable of imagining a violent crime being a part of her life; she saw drops of blood, and she stretched her imagination in order to supply a plausible narrative for it. She wasn’t capable of imagining that her roommate’s bloody, half-naked body was in the next room, behind a locked door.

But Knox’s naïvete didn’t stop there. She believed that the police’s objective was to discover the truth, and that if she just acted like herself and told the truth, her innocence would be obvious to everyone around her. “Since I hadn’t been involved in the murder,” she writes in her recent memoir, Waiting to Be Heard (2013), “I figured that anything I said would only help prove my innocence.”

Knox signed the statement confirming her “vision” of the murder after her fourth police interrogation. Technically, she went into each of those interrogations as a witness; on the night of the fourth one, she was only at the station to keep Sollecito company during his own interrogation, and the police’s decision to question her again seemed to her both redundant and spontaneous, as if it was happening only because she was there and they needed something to do. In fact, she’d been evolving from a witness to a suspect without her knowing it. And, even when she was in a room full of shouting police officers, it didn’t occur to her that they were trying to implicate her. She believed they were trying to help her remember the night in their joint effort to find the truth about what happened to Kercher. So, after Sollecito broke under pressure and ruined her alibi, saying that it was possible that, while he’d been asleep, Knox had left his apartment, she believed that maybe she really had. Under pressure, believing what the police were feeding her, she wondered if maybe she’d forgotten leaving his apartment because she’d been stoned. She strained her memory to recall what she thought she might be forgetting. And as the night stretched on into the wee hours, without food or drink or bathroom breaks, with a room full of police officers bearing down on her in a language she wasn’t fluent in, she strained until the vision she had of herself at the scene of the murder materialized and became plausible. She thought she could have left Sollecito’s, and she couldn’t understand why her memory had failed her, so she struggled to furnish the planted, phantom blank.

The statement the police wrote for Knox ended with the line: “I remember confusedly that he [a man named Patrick Lumumba, whom Knox had texted on the night of the murder] killed her.” After Knox signed this, the police in the room embraced each other, Knox started hitting herself in the head, a police officer took Knox to the canteen for espresso, and then arrested her. Later, Knox penned a second statement, in which she wrote:

[I]t was under this pressure and after many hours of confusion that my mind came up with these answers. In my mind I saw Patrik [sic] in flashes of blurred images. I saw him near the basketball court. I saw him at my front door. I saw myself cowering in the kitchen with my hands over my ears because in my head I could hear Meredith screaming. But I've said this many times so as to make myself clear: these things seem unreal to me, like a dream, and I am unsure if they are real things that happened or are just dreams my head has made to try to answer the questions in my head and the questions I am being asked.

The problem was that Knox, even in jail, didn’t grasp that she was in trouble. She believed that she and the police were united in their quest to discover the truth. And she thought she was behind bars for her own protection. She thought, when they took her to jail, that she was going to some kind of special holding cell. And so she persisted in trying to explain herself. She indulged the vagaries of human consciousness the way only the writer she wanted to be would:

The police have told me that they have hard evidence that places me at the house, my house, at the time of Meredith's murder. I don't know what proof they are talking about, but if this is true, it means I am very confused and my dreams must be real.

She was certain, though, that, even if she was there, she didn’t commit the crime. “All I know is that I didn't kill Meredith, and so I have nothing but lies to be afraid of.”

So she persisted in her faith that, if only she could explain herself properly, her situation would resolve itself. And so she asked, despite opposition from her lawyers, for a face-to-face with the prosecutor. She felt that if she could just talk to him in person he would have no choice but to recognize the truth of her essential innocence.

¤

Mignini is an easy guy to write off. He’s unapologetic about his tendency towards conspiracy theories. He has a history of obsession with violent crimes involving sex. In 2008, Douglas Preston published a book called The Monster of Florence about a killer who, between 1968 and 1985, targeted couples making out or having sex in cars, sometimes removing the female victims’ genitals. The case was never solved. Mignini became involved in 1985, when police recovered the body of a doctor named Francesco Narducci from Lake Trasimeno near Perugia. Mignini was convinced that Narducci and his father were part of a secret society that was somehow involved in the killings. His theory involved a complicated conspiracy that included government officials and law enforcement officers. Mignini indicted 20 people and even arrested Mario Spezi, an Italian journalist who worked with Preston on the book, for complicity in the homicides. Eventually, in 2010, Mignini’s zeal in the case would lead to his conviction for abuse of office.

Mignini grew up in a Perugia that was both deeply Catholic and steeped in the legacy of its pagan roots. (In particular, the city has a strong Masonic presence.) And so when Mignini arrived at a crime scene that included the blood of a black cat spattered against a wall (albeit in the downstairs apartment at 7 Via della Pergola rather than the upstairs apartment, where Knox and Kercher lived), a break-in that looked to him to be staged, and single bloody footprints leading out the door (the removal of one shoe being a piece of pagan symbolism used in Masonic initiation), it satisfied Mignini’s every expectation for what should accompany grisly crimes, and for what details should accompany true evil.

Amanda Knox satisfied Mignini’s internal narrative too. His childhood home was beside a women’s prison; as a kid in the ’50s, Mignini would look out the window and watch the women exercising on the roof. He’d done this so much that his mother had had to ask him to stop. Torcoletti’s most high-profile inmate at the time was the beautiful Caterina Fort, who’d murdered her lover’s wife and three young children with a tire iron. Psychiatrists would go on to study Fort extensively because, while she confessed to killing her lover’s wife, she seemed to have entirely blocked the memory of killing the three children. So, when Mignini found an attractive young woman behaving erratically, whose story of coming home and showering in a bathroom with blood spots on the sink made no sense to him, and who seemed open to the idea that she’d forgotten what happened on the night of November 1, Mignini’s wheels started turning.

¤

There are, by now, several accounts of Knox’s story. Candace Dempsey’s Murder in Italy: The Shocking Slaying of a British Student, the Accused American Girl, and an International Scandal (2010) reads like a pure sensationalist crime story, making heavy use of dramatic one-liners to end sections and chapters, such as

Now, on the morning of November 1, Meredith slept for the last time on this earth.

and

Soon police would draw a circle around Meredith’s social set and tighten it like a noose.

Dempsey doesn’t doubt Knox’s innocence. But she’s careful to establish her naïvete. She describes a personality type that feels familiar to me from college, where I felt like I knew a dozen Amanda Knoxes, girls who called everyone “friend” but who were obviously not as impossibly happy as they presented themselves; girls whose do-gooder optimism felt like a form of willful denial.

Barbie Nadeau, the author of Angel Face: Sex, Murder, and the Inside Story of Amanda Knox (2010), on the other hand, is certain Knox did it. Her version corroborates the prosecution’s version of a sex game gone wrong, except that Nadeau believes that Knox and Sollecito, rather than seeking revenge on Kercher for her too-serious ways, were in the house to do a drug deal with Guede and simply got so high that they “lost touch with their own rational selves.” Nadeau speculates that Sollecito’s history of experimentation with drugs (mostly just hash, but also some cocaine and acid) could’ve made for a dangerous combination with Knox’s familiarity with “hard A” from the University of Washington party scene. “By sharing their knowledge, two experienced thrill seekers could have found a way to get higher than ever — with lethal consequences.”

The problem, however, is that this story relies on evidence that has long ago been debunked. Nadeau refers to the bloodspots outside Meredith’s room that were described at one time as containing Kercher and Knox’s “mixed” DNA. That Knox’s DNA would be mixed with Meredith’s blood wouldn’t be surprising, given that they lived in the house together. But the prosecutors presented this mixed DNA as something that could only happen if Knox’s blood were mixed with Kercher’s blood. Nadeau lets this misrepresentation stand and she does the same thing with the footprints in the hallway. There were two small bare footprints outside Kercher’s room that were once thought to have been Knox’s, and to have been left in blood; a chemical called luminol detects the possibility of cleaned-up blood and the use of this chemical uncovered these footprints. But luminol only indicates the possibility of cleaned-up blood rather than the certainty of it; it reacts with a number of other substances, including rust, urine, and the bleach in the bleach-based cleaning product Knox and Kercher used on their floors. Follow-up tests with tetramethylbenzidine came up negative for blood on these footprints, but Nadeau doesn’t mention this.

In Murder in Italy and Angel Face, Dempsey and Nadeau are fundamentally interested in one question: whether or not Knox did it. Where Nadeau sees guilt, Dempsey sees innocence. In The Fatal Gift of Beauty: The Trials of Amanda Knox (2011), however, Nina Burleigh is more interested in the full scope of the story. She fleshes out the character of Mignini, giving us a sense of the internal narrative he brought with him to the crime. And Burleigh gives an illuminating account of Rudy Guede, the man whose DNA was found at the murder scene, a figure to whom neither Dempsey nor Nadeau (nor Sollecito and Knox, in their memoirs, for that matter) pay much attention.[2]

¤

In Waiting to Be Heard, Knox describes her December 2007 face-to-face with Guiliano Mignini:

“I’m sure if I talk to him in person, I can show him I’m sincere,” I told my lawyers. “I can convince him he’s been wrong about me. It bothers me that everyone — the prosecutor, the police, the press, the public — thinks I’m a murderer. If I just had the chance to present my real self to Mignini I’m sure I could change that perception. People could no longer say I’m a killer.”

Her lawyers didn’t like the idea, but Knox was persuasive: “My thought was that I had misled the police. I needed to take responsibility for my mistake. It seemed like the right, and adult, thing to do.”

At their meeting, Mignini, flanked by two police officers, and Knox, flanked by her lawyers, sat at opposing tables in a dim room with barred windows. Knox writes:

The tension was instantly obvious […] [H]e started firing questions at me immediately […] What has stuck with me the most is that he never looked me in the eye.

Mignini kept his eyes on his prepared list of questions. “[W]hen I answered, he would reject my response and ask again.” Mignini guided the conversation to the “confession” Knox had signed after her fourth interrogation. The prosecutor focused on two points. The first was that Sollecito had said that maybe she’d left his apartment while he’d been asleep. Coming from the police, who she believed were on her side in their joint quest for the truth surrounding Kercher’s murder, Knox believed this. And the second was the text message she sent to Patrick Lumumba, the Congo-born bar owner Knox had worked for in town whom she had implicated in her confession, and whose role in the crime the police would essentially replace with Rudy Guede once it became clear that Lumumba’s alibi — that he was at work at the bar at the time — was iron clad, and once the evidence unequivocally placed Guede, another black immigrant, in Kercher’s bedroom.

On the night of November 1, Lumumba had texted Knox saying she didn’t have to come to work at Le Chic, the pub he owned where she was a cocktail waitress. Knox texted him back, writing “Ci vediamo piu tardi buona serata!” This translates to “See you later. Have a good evening!” But “see you later” in English doesn’t translate perfectly into Italian, and the police thought it meant that Knox was making plans to meet up with Lumumba. During her fourth interrogation, the police used this to persuade Knox that she really did have plans to meet Patrick, and that she was forgetting something. In their face-to-face, Mignini focused on Lumumba too.

“Why did you name Patrick?”

“The police insisted I’d met the person I had sent the text message to.”

“No. Why did you name Patrick?”

“The police had been asking me about Patrick.”

“No! Why did you name Patrick?”

“The police insisted it was Patrick.”

He was more and more aggressive about it. “Why Patrick?”

“Because of my message.”

“That doesn’t explain why Patrick.”

“Yes, it does.”

“Why did you say Patrick killed her?”

“Because I was confused. Because I was under pressure.”

“NO!” he insisted. “Why did you say Patrick?”

I was more frustrated than I’d ever been. “Because I thought it could have been him!” I shouted, starting to cry.

I meant that I’d imagined Patrick’s face and so I had really, momentarily, thought it was him.

Mignini jumped up, bellowing, “Aha!”

Mignini was not alone in laying eyes on Knox and detecting certain guilt. I read Waiting to Be Heard while sitting in an Italian coffee shop down the street from my apartment in Hollywood. I did this on purpose, because I was wondering whether or not any Italians would approach me to say something. One lady did, and she was certain Knox was guilty. I said there wasn’t any hard evidence, that if Knox had killed Kercher, she would have had to scrub the crime scene of her own traces while improbably (or, impossibly) leaving behind only Guede’s. The lady’s look towards me became wary and all she could manage in response was the observation that Knox didn’t cry after Kercher’s death.

There’s something about Amanda Knox that cuts through logic and taps a more primal lobe of the brain. She provokes intuitive reactions in people. For me, the YouTube video of Knox and Sollecito comforting each other outside 7 Via della Pergola isn’t disconcerting. But I can barely make eye contact with Knox’s photo on the cover of her memoir. Her expression comes across as a transparent plea for sympathy, one that looks like feigned pain to mask indignation, feigned girlhood to mask sexuality, even feigned pain to mask true pain. After four years of prison and international pillory, I have no doubt that Knox has suffered. But the photo feels somehow unbearably false. If somebody had just snapped an iPhone shot of her without her knowing it, she’d have been infinitely better off. But in posing, what’s sincere about her has become warped in such a way as to trigger my instinct to distance myself.

The best authority on how people react to Amanda Knox is Douglas Preston, author of The Monster of Florence. His Kindle Single Trial by Fury (2013) focuses on why people hate Knox so much. He quotes some of the easy-to-find stuff being said about her on the internet, like

The bitch needs to die naked tasting her own blood.

and

There are a whole lot of women who instinctively think she is a total fake, has not fooled any one of us, believes she is foul to the bone and we hope she rots in prison and dies in hell.

Preston theorizes that the act of punishment lights up a pleasure zone in our brains, because group evolution relies on cooperation and therefore must include the ability to punish those who don’t cooperate or who are seen as outsiders. In daily life, our ability to indulge this pleasure is limited; on the internet, the desire to punish is unregulated. But Preston’s theory doesn’t explain why people hate Knox more than they hate, say, Casey Anthony. And he doesn’t explain why Knox managed to get locked up for a crime she didn’t commit. What is it about Amanda Knox, in particular, that turns us against her?

What’s compelling to me about Amanda Knox is that it was her slight offness that did her in, the everyday offness to be found on every schoolyard and in every workplace. This is the slight sort of offness that rouses muttered suspicion and gossip, the slight sort of offness that courses through our daily lives and governs who we choose to affiliate ourselves with and who we choose to distance ourselves from. It’s an offness we detect instinctively. This slight sort of offness is a hint that triggers our instinct to go into Darwinian mode and define our pack. For zebras, it’s the slow and feeble who fall behind the harem. For us, it’s the people who behave inappropriately.

To form an opinion on Amanda Knox is, to me, to cast a vote of loyalty on a number of pack-defining questions. Do you trust the word of the Italian authorities or that of a sexually open young woman? Does it matter to you that those authorities are Italian and not American? That the Italian prosecutor was a devout Catholic? Do you really believe that all innocent people cry in the immediate aftermath of traumatic death? Are there other options? Do you believe that you have the power to look into a young woman’s eyes in a grainy YouTube video and decide whether or not her soul is possessed by the devil? Do you care about the facts or about the greater truth of gut instinct? Do you, like Amanda Knox did, and like I think most writers do, believe that if you can explain things in just the right way the truth about yourself will become obvious? To explain things “the right way” — does that mean to explain things logically or plausibly? Are facts there just to make our internal convictions seem plausible? Is truth internal or external? Are our legal systems designed to satisfy our collective desire for punishment? Or are they supposed to discover truth? Is it possible that truth in the justice system either in Italy or the United States or both is completely beside the point, just as it is in a good story? Do you believe it’s good that Amanda Knox matured and learned how to stop trying to explain herself to jailers and prosecutors and police officers who used a language barrier and their own internal conviction to turn whatever she said into self-incrimination? Or do you think it’s sad that she had to put up that wall? Is the truth about how we feel something we reserve for the protected, free space of fiction?

In my novel, the protagonist musters his courage and commits a crime serious enough to land him in jail. He winds up in a holding cell of the sort Knox thought she was being taken to, and he stays there for long enough to tell his story. Eventually, though, at the end of the book, he has to go back to life.

Amanda Knox hasn’t been able to do that yet; and one begins to wonder whether she ever will, or whether there’s something about her that means she’ll always be under suspicion. There’s no set of circumstances that could convince everyone, that could convey the innocence that Knox feels insider herself to be so obvious. True, Rudy Guede could speak out, or a secret surveillance video of Meredith Kercher’s bedroom on the night of her murder could surface. But that fantasy surveillance video, I think, would merely compel Mignini to recast Knox as some kind of behind-the-scenes mastermind.

For most of us, slight offness doesn’t lead to incarceration. But it does expose us to awkwardness and rejection, and put us in the position of having to persuade the pack that, the odd behavior we’ve evidenced notwithstanding, we’re actually healthy. To establish a motive, Mignini claimed that Knox hated Kercher enough to kill her. Knox, in her memoir, insists that she and Kercher were friends. Burleigh, meanwhile, establishes a dynamic that feels most true to me. Though Knox and Kercher got along when they first moved in together, in time Kercher distanced herself from her roommate. Kercher’s British posse of friends didn’t like Knox either. At the bar, Knox positioned herself between conversations, talking, yes, but talking to nobody, like she wasn’t really a part of things. Amanda Knox was out of sync.

Reading this, and about her behavior after Meredith Kercher’s murder, it doesn’t surprise me that Amanda Knox is a writer. When she first went to prison, she was certain that if she could just explain herself correctly, her captors would set her free; the problem was not her, but how she expressed herself. And I’m not locked up, but this is why I write, too: to repair the communicative breach that I think stands between me and a freer, better life.

¤

Tom Dibblee is the editor of Trop.

[1] A police officer selected a knife at random from Sollecito’s kitchen drawer based on “investigator’s instinct,” and this knife, despite not fitting the wound on Kercher’s neck or the knife print in blood on Kercher’s bed, was put forward as the murder weapon. In the first trial, the prosecution claimed Knox’s DNA was on the handle and Kercher’s was on the blade. In the appeals trial, an independent review of the “biological matter” on the blade revealed that it was actually potato starch or rye bread. And, a bra clasp found in Kercher’s bedroom that was said to contain Sollecito’s DNA was found in the appeals trial to have been mishandled, likely contaminated, and to contain DNA so mixed as to point to any number of people. The prosecution introduced it as evidence only once a Nike shoe print that had been left in blood was found not to be Sollecito’s.

[2] Guede came to Italy from the Ivory Coast as a child. His mother didn’t accompany him and his father when they moved. His father beat him and sometimes left him locked out of the house to sleep on the streets at night. He was subsequently adopted, at the age of 17, by one of Italy’s richest families. His foster father got Guede a job, and when he didn’t show up for it, his foster father kicked him out of the house. Guede started sleeping on the floor at a friend’s place for reasons the friend didn’t quite understand. While there he’d carry on conversations in a zombie-like state, conversations that, in the morning, Guede couldn’t remember. He burglarized a law office with a rock through the window (much like the rock that was thrown through the window at 7 Via della Pergola). A few days before the murder he got caught breaking into a nursery in Milan with a knife on him. His psychotic fugue states are consistent with the trauma that characterized his childhood. He was out of money. He hadn’t killed before; Kercher’s neck wounds point towards the work of an amateur, the towels on her neck point indicate that somebody tried to stanch Kercher’s bleeding, the duvet over her body indicate that the killer felt regret. I’m with Burleigh and Rich in saying that the evidence points to a burglar who panicked when Kercher came home unexpectedly.

LARB Contributor

Tom Dibblee's fiction is forthcoming in Glimmer Train. He edits Trop at tropmag.com and he has an MFA from CalArts.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!