Ode to Survival: On Saeed Jones’s “Alive at the End of the World”

Christos Kalli examines Saeed Jones’s encounters with the end of the world in a poetry collection about survival, “Alive at the End of the World.”

By Christos KalliMarch 4, 2023

Alive at the End of the World by Saeed Jones. Coffee House Press. 104 pages.

Live not for battles won.

Live not for the-end-of-the-song.

Live in the along.

—Gwendolyn Brooks, “Speech to the Young”

the morning we rose

from our beds as always

listening for the bang of the end

of the world

—Lucille Clifton, “the beginning of the end of the world”

IN A TIME of proliferating wars, sobering environmental disasters, ongoing and looming pandemics, so-called cultural deaths, AI-inspired humanitarian crises, persistent land co-optation, and inexhaustible doomscrolling, it seems that we endlessly discuss the end of the world at the same time that we don’t discuss it enough. The title of Saeed Jones’s Alive at the End of the World (2022) unveils a paradox: How can you be alive if it is the end? Is it really the end if you are alive? In his new collection, what it means to be alive, what it means to be at the end, and what it means to be alive at the end of the world—as a Black queer body, navigating personal grief and collective historical traumas—turn the impossibility in the title into the possibilities of radical survival.

Jones portrays the mode of survival that is necessitated almost through the bifocal lens of his poetic progenitors, Gwendolyn Brooks and Clifton: living in a type of indeterminacy that Brooks’s makeshift noun “the along” suggests, while the “bang at the end / of the world” plays in the background, like routinized white noise, as it does for Clifton. Drawing from the Black queer pastoral turns of his debut poetry collection, Prelude to Bruise (2014), and brimming with prose-narrative poems that seem to migrate from his memoir, How We Fight for Our Lives (2019), Jones’s new book composes an ode to survival and redefines extinction. In his characteristic tonally sublime verve—with poems that undulate from the tragicomic to the satiric, with killer jokes and jokes about killers—Jones looks the apocalypse straight in its eyes and provides a piercing account of the cycle of ends.

The end of the world is defined in many ways in Jones’s book—as “a boy who feels all the pain we give him / but never bruises,” “a father who bragged about the broken / roof he kept overhead,” “a nightclub” guarded by “[d]rag queens with machetes and rhinestoned // machine guns.” In the opening poem, eponymously titled “Alive at the End of the World”—the first of five poems with the same title, each of the subsequent four commencing the four main sections of the book—the end takes its shape in the context of the nation, as “just another midday massacre / in America.” Never one to shy away from critique, Jones turns his eyes on his country:

In America, a gathering of people

is called target practice or a funeral,

depending on who lives long enough

to define the terms. But for now, we

are alive at the end of the world,

shell-shocked by headlines and alarm

clocks, burning through what little love

we have left. With time, the white boys

with guns will become wounds we won’t

quite remember enduring.

In this portrait of America-as-postapocalyptic-space, in which mass violence has become unremarkable and part of daily routine, the sociability that is related to “a gathering of people” is disrupted and replaced by an invitation to violence: to gather with people is now to be targeted or buried. Invoking, but never fully articulating, current conversations around gun control, Jones assumes the collective “we”—a grammatical gesture that attempts to restore the sense of community that is fractured—and argues that survival is still there, even if impermanent and only “for now,” even if love needs to be turned into a fuel that is burned for warmth. From this present survival, and the past and ongoing violence against “people,” Jones uses the future tense to push us towards a hopeful prospect. In the aftermath of survival, “the white boys / with guns” who inflict injury will be erased and eventually will only remain as the long-forgotten physical manifestation of that violence, a metamorphic image that exemplifies the emotional-aesthetic intricacy of Jones’s writing. At the same time as this poem sets in motion the book’s critique of the United States and whiteness—developed later in poems such as “A Song for the Status Quo” and “Heritage”—it also emphasizes collective endurance.

When the book’s title reverberates again in the opening of the first section, this endurance is portrayed as a much more personal and complicated pursuit. Switching to the first-person singular pronoun “I,” yet keeping the physicality of the body as an extension of the psyche, the poetic voice describes another encounter with a series of ends:

The world ends and I make a dress

out of the names I live to inflict

on myself. Painful to put the dress

on, even more painful to take it off.

I banish the dress to my closet as long

as my body can bear. The world ends

again so I drag the dress out, bandage

myself back into the truth of beauty.

Refusing to define the nature of this apocalypse and to contextualize the poetic voice’s reaction to it, the poem asks the readers to roll up their intellectual sleeves in order to understand how the metaphoric dress functions in relation to the end. Is it ammunition, protection, healing, self-destruction, or a combination of all? In the elliptical atmosphere of the poem, the making and donning of the dress, the closet, the body, all become significations that are charged with queer energy. This energy informs the ambiguities of the poem and turns the dress made out of the names inflicted on the self into sharp commentary on self-degradation and self-harm in the LGBTQ+ community, on the ways in which even the self can be made to pose a threat to the self.

This description of the dress hearkens back to Jones’s previous poetry collection, Prelude to Bruise, and specifically the poem “Postapocalyptic Heartbeat”—a clear predecessor of this book—in which the poetic voice says “I didn’t exactly mean to survive myself.” Yet, the difficulty of this poem—a quality, in Jones’s writing, that is always synonymous to richness—opens the poem to interpretations that complement this queer reading. The economy of Jones’s diction, as well as the immaculate enjambments that hold the reader over the edge, produce an eerie feeling looming over what is described, something unspoken but lurking. The continual cycle in which the world keeps ending and the dress is put on compels the reader to both focus on and move beyond the self, to interpret what is inflicted not only as derogatory self-epithets but also the proper-noun names of others. In this context, the pain of donning the dress and the equally heavy pain of not doing so become akin to the processes of remembering and honoring names, of grief and sorrow.

Expanding on the work of bereavement and commemoration of his previous books, Jones focuses on many facets of grief in his most recent. The penultimate poems of all four sections constitute a series on grief that Jones, like a parent who cannot find names for all his children, titles numerically: “Grief #213,” “Grief #913,” “Grief #346,” “Grief #1.” In “Grief #213”—inspired, as the “Notes at the End of the World” section attests, “by a 2015 essay [he] wrote for BuzzFeed News titled ‘Self-Portrait as an Ungrateful Black Writer’”—Jones mourns linguistic and behavioral cues in the presence of a racism that is concealed:

I grieve forced laughter, shrieks sharp as broken

champagne flutes and the bright white necks I wanted

to press the shards against. I grieve the dead bird of my right

hand on my chest, the air escaping my throat’s prison,

the scream mangled into a mere “ha!” I grieve unearned

exclamations. I grieve saying “you are so funny!” I grieve

saying “you’re killing me!” when I meant to say “you are

killing me.” I have died right in front of you so many times;

my ghost is my plus-one tonight.

Using anaphora with the repetition of “I grieve,” Jones lists responses to something that is kept out of the poem yet hinted at and racially charged by the theoretical violence enacted on the “bright white necks.” In her 2014 interview with The New Yorker, Claudia Rankine, who has written extensively about microaggressions in her book Citizen (2014) and elsewhere, has called the behavior that elicits the speaker’s reaction here “invisible racism”—racism that exists in the interstices of overt communication and attitude, as an apparitional and fleeting but very real presence in the social dimension. In “Grief #213,” the type of racism that expects “laughter” and “exclamations” is unveiled and dismantled through not only Jones’s language, punctuated by the ironic grievance, but also the tone that lies below his diction’s surface. At once comic and serious—a combination encapsulated perfectly by the line “I have died right in front of you so many times; / my ghost is my plus-one tonight”—Jones conjures a sarcasm that is so acute it could reap a hole in the universe. Such tonal ingenuity is common in Alive at the End of the World, quintessentially so in the poem “The Dead Dozens,” an elegy for his mother in the structure of a yo mama joke. At a time when tone is often sidelined as a formal characteristic in contemporary poetry and often examined as an exclusively prose feature, Jones’s masterful tonal maneuvers allow him to navigate grief and whiteness.

It is this relationship with grief, as well as the bigger ramifications of this relationship, that is encountered at the end of Jones’s world. In the sequence poem titled “Saeed, or the Other One,” comprised of four parts that bookend the four sections of the book, the author recounts an incident after a reading. An audience member confronts Jones with a question that Jones himself has often confronted his readers and himself with: do you possess your pain or does your pain possess you? Written entirely in prose—a formal investment here that is informed by his memoir, resulting in single-stanza, single-line prose poems and autofictional narrative ones—“Saeed, or The Other One” explores the consequences of that question and how it leads to a meeting with “The Other One,” pain embodied as an identical counter-self. Without spoiling the searing account, it ends by teasing the seductiveness of consigning pain as the dominant self in order to survive.

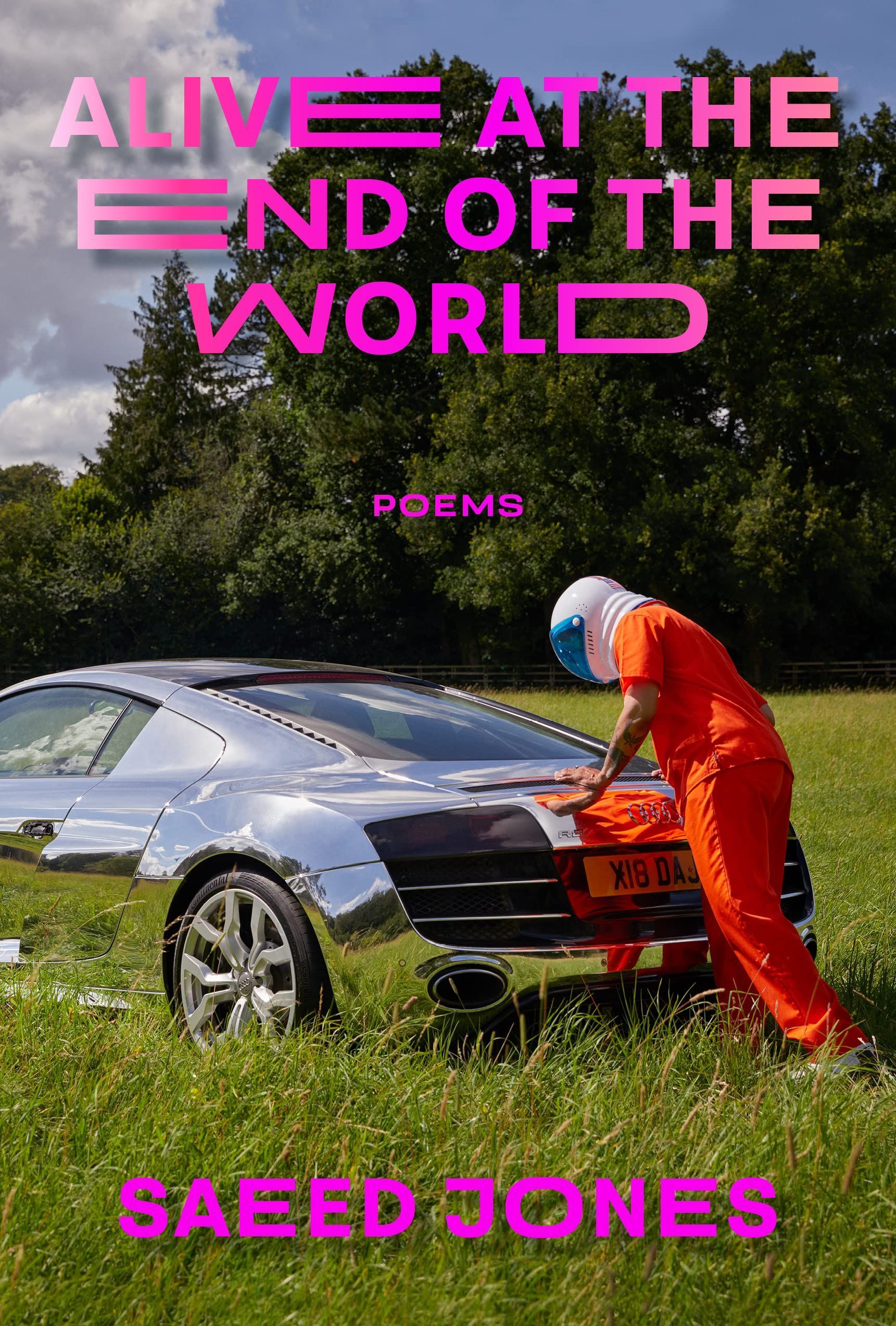

To reflect on this tension, I step out of my apartment in London, cross the Waterloo Bridge, and walk along the River Thames. To my left, a huge black board announces, in white capital letters, that “THERE ARE BLACK PEOPLE IN THE FUTURE.” As I approach it, I realize that it presents the entrance to an exhibition at the Southbank Centre titled In the Black Fantastic. Ekow Eshun, the British Ghanaian curator, brings together contemporary artists of the global African diaspora—such as the British Trinidadian Chris Ofili, the American Kara Walker, and the Kenyan Wangechi Mutu—who use “myth, science fiction, spiritual traditions and folklore in order to address racial injustice, reimagine historical events and create alternate realities.” In the exhibition, many of the pieces quickly begin to remind me of the cover of Jones’s book, a photograph by the American artist-activist Lola Flash, titled “Keep on Pushin’,” as part of her newest series syzygy, the vision (formerly called Afrofuturism).

Traditionally used almost as an epigram for encouraging people to overcome challenges, this idiomatic saying is visualized on the cover by showing a figure wearing a white-cerulean astronaut helmet and an orange outfit (reminiscent of a prison uniform) pushing a silver and possibly out-of-gas luxury car in an overgrown meadow (think queer hybrid of Daft Punk and Back to the Future). At once an admonishment of the racial injustices in the judicial-carceral systems, an ecocritical commentary, and a posthumanist critique, the cover image transforms the simple and physical labor of pushing a car forward into a deeply political, if not existential, push against systemic structures. Flash’s photograph complements beautifully the ways in which Jones’s Alive at the End of the World pushes forward. The resistance against letting go, even at the end of it all, is evident throughout and most powerfully with the final word of the book, which is “—continued.”

When Cornelius Eady published his collection All the American Poets Have Titled Their New Books “The End” (2017), he knew that poets have been contemplating our ends for some time, and that we ought to listen. In the title poem, Eady asks “How many books now have the word Last / In their title?” Today, we can also ask: how many artists, inside and outside exhibitions and books, examine our collective futures, their personal survivals, and their communities’ ability to last? Not coincidentally published two months before The World Keeps Ending and the World Goes On, by contemporary Korean American poet Franny Choi, Jones’s book is relevant and important in the ways in which it connects not only with current global art movements but also contemporary and historical conversations that are often informed and enriched by art. It is a collection about lastingness that will last. And it is a great companion for the end of the world.

¤

Christos Kalli is a poet and poetry critic. Visit him at www.christoskalli.com.

LARB Contributor

Christos Kalli’s poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Prairie Schooner, Ninth Letter, The Adroit Journal, and The National Poetry Review, among others. He has written criticism for the Harvard Review, The Hopkins Review, and World Literature Today. Visit him at www.christoskalli.com

LARB Staff Recommendations

“Muscle Memory” by Jenny Liou

Living Everywhere: On Adam Zagajewski’s “True Life”

Kathleen Rooney reviews Adam Zagajewski’s “True Life.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!