Not in This Together

Laila Lalami on what Rousseau has to teach us about the pandemic.

By Laila LalamiAugust 10, 2020

FEBRUARY WAS ONLY six months ago, but it belongs to a different era. Back then I still thought that, notwith-standing different private interests, moral values, and group allegiances, the United States could still function as a democratic society. I remember I was visiting Amherst College to take part in a public conversation with the novelist Susan Choi on the art of fiction. After the event, we signed books, shook hands with attendees, and went to dinner with our hosts in a packed restaurant. The next morning, I took a walk around the campus, ending up at the local bookstore, where I picked up and put down a dozen different novels before settling on one. Phrases like “aerosolized droplets” and “surface contamination” had not yet entered my daily vocabulary.

At the time, the United States had identified only a few dozen cases of the novel coronavirus, most of them linked to an outbreak on the Diamond Princess, a cruise ship that had docked in Yokohama, Japan. Though the disease was difficult to treat, the preventive measures advanced by epidemiologists — washing one’s hands with soap and covering one’s mouth when coughing — were easy. I assumed that COVID-19, like its antecedent SARS, would require a range of federal measures, including the confinement of travelers who came from affected countries. Containment seemed not only possible, but likely.

On the flight back to Los Angeles, my phone lit up with a news notification: the governor of Washington had declared a state of emergency after a man in Seattle had died of the coronavirus. He was believed to be the first victim of COVID-19 in the United States. Even then, I wasn’t alarmed. Whether out of misplaced trust in the Centers for Disease Control or a belief in the social contract, I failed to imagine that a single death could be the harbinger of a plague.

Denial was impossible to sustain for long. The Centers for Disease Control issued faulty tests that made it impossible for states to diagnose and isolate patients, then took weeks to correct the problem. The Department of Health and Human Services sent workers without protective gear or infection training to evacuate infected Americans from Wuhan, China. The Department of Homeland Security allowed travelers to fly into and within the country with few or no preventive restrictions. The president claimed that the virus was a “hoax,” that it was “under control,” and finally that it would simply disappear, “like a miracle.” One by one, American institutions ignored or renounced their responsibility for controlling the virus.

The dereliction of duty was compounded by incoherence and incompetence. Experts from the White House Coronavirus Task Force issued social distancing guidelines, only to have the president say they could be relaxed by Easter. Public health officials discouraged Americans from wearing face masks, then reversed themselves on April 3, when the number of fatalities nationwide had already reached 5,374. Of course, scientists routinely change their recommendations based on empirical data, but the contradictory messaging from elected officials irretrievably damaged efforts at containment.

Left to manage the crisis, states, counties, and cities made drastically different decisions about whether it was safe to work in an office, go to school, eat at a restaurant, take public transport, attend religious services, or vote in elections. It was possible, in the strange spring of 2020, to drive no more than 50 miles in any direction in the United States and encounter different realities: one where people were allowed to gather in large crowds; one where they were limited to 50 persons; and one where they were prohibited from gathering altogether. Each state, county, and city behaved as if its survival was independent of others.

In The Social Contract, Rousseau expressed some skepticism that large nations could be well governed. They require a hierarchy of administrations, he argued, each reporting to the one above it, burdening the people with additional taxes and leaving them “hardly any public revenue available for emergencies.” Furthermore, he said, laws and customs will differ from province to province, which “creates misunderstanding and confusion” and in the end weakens the social bond between the people.

Rousseau himself was born in a tiny state — the Republic of Geneva — but that fact alone doesn’t explain his distrust. He allowed that there are some benefits to large nations — a stronger ability to withstand external attacks, for example — but in general he felt that good government becomes “more difficult over great distances” and that the acrimony between different central and provincial administrations tends to “absorb all political attention,” which leaves little time to “study the people’s happiness.”

These warnings seem particularly apt for the present moment. The United States has confronted many emergencies, from floods to hurricanes to wildfires and, although it has not always managed them well, it has survived them all. The pandemic is different. Not in a century has the nation faced a health crisis that threatens the lives of so many of its citizens and tests the bonds they hold as a people.

¤

What was relatively clear from the start was that the incubation period for the coronavirus was two to 14 days. After Los Angeles went into quarantine, I looked at my calendar each morning, counted back 14 days, and deduced that my family was safe from this dinner at the restaurant or that night at the movie theater. Every sneeze was suspect, every cough was cause for panic. And all anybody wanted to talk about was when it would be safe to “return to normal.”

“Normal” meant a nation with an extremely complex health-care system, which delivers different levels of private or public care depending on employment, age, and income. “Normal” meant 2.3 million people in prisons or jails, with little opportunity for physical distancing or proper hygiene. “Normal” meant large indigenous reservations that still have poor access to running water and few hospital beds. “Normal” meant labor conditions that have forced a growing number of Americans to hold two or three jobs in order to make ends meet. The pandemic revealed and exacerbated these abnormalities, forcing the body politic to notice them.

We now know that the virus spread quickly to poor neighborhoods, where residents are more likely to live in multigenerational households, work in jobs deemed essential during shelter-in-place orders, and have little or no access to health care and paid sick leave. The prison system became host to massive clusters of cases, as did senior care facilities. Indigenous reservations, too, were particularly affected. The Navajo nation, for example, had more deaths from COVID-19 than 15 other states. Data collected nationally shows a clear racial pattern for infection and deaths, with Hispanics and Latinos getting sick at greater rates than whites, and African Americans dying at higher rates than whites.

Addressing these inequalities might have made the body politic stronger and therefore better able to handle the pandemic, but even when the disproportionate impact of the virus on vulnerable populations was clearly documented, there seemed to be no political will to address it. Prisoners were often denied early release. Native tribes were told they couldn’t limit traffic into their reservations. Essential workers worked double or triple shifts without protective equipment. It’s not entirely surprising that the number of confirmed cases and fatalities soared, reaching 63,000 by May 1. The afflicted were treated in isolation and, if their treatment failed, they died in solitude, their funerals held in private.

While the loss of life was shielded from view, the loss of livelihoods was quite public. The closure of businesses of all kinds during shelter-in-place orders resulted in the abrupt loss of some 40,000,000 jobs. In Florida, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, so many people filed unemployment claims that computer systems crashed. Lines at food banks in wealthy cities like Los Angeles and New York stretch for miles. Nearly a third of US households are missing rent or mortgage payments. The economic disaster dominates front-page coverage, relegating the human toll to other sections.

So often I had heard Americans say they wanted their country to be run like a business. In fact, this was one of the most common arguments advanced in favor of Donald Trump. The outcome of that reasoning is already plain. People who have money can stay safe at home, streaming television shows and perfecting their baking skills, while those on limited incomes have to work and risk infection, or stay home and fear eviction. The expectation that elected representatives would make decisions based on the common good, as Rousseau had imagined, seems almost quaint. Instead, private interest appears to be the main driving force behind reopening plans, a sign that the social bond has withered.

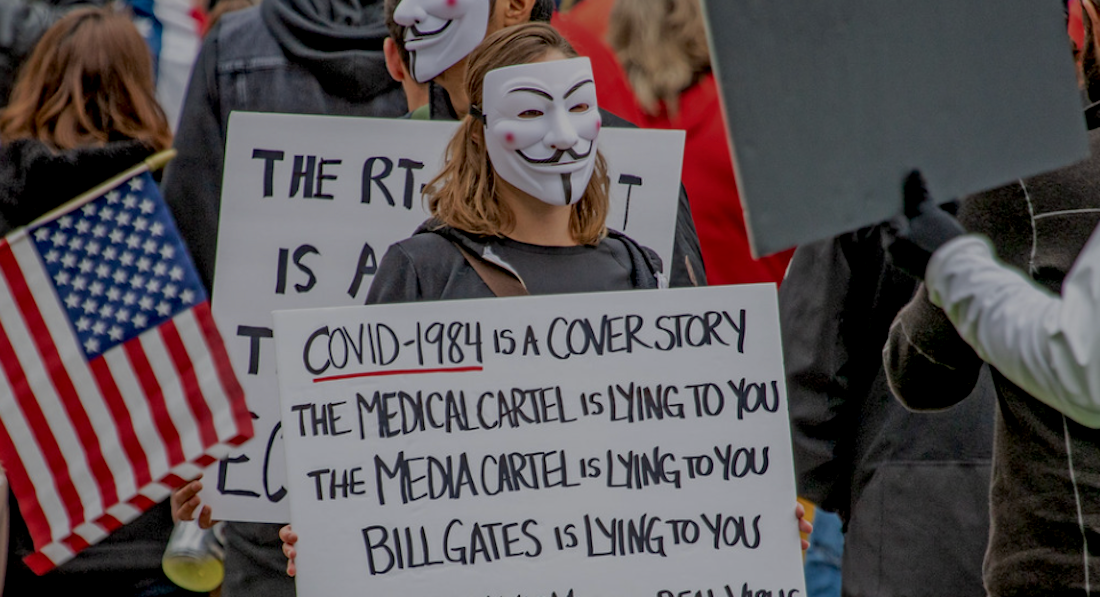

Equally troubling is the fact that some Americans are treating public health advice — maintain physical distance, wear a mask, avoid gathering with others not from your household — as an imposition on individual freedoms. One morning in late May, while I was waiting to cross at an intersection in Santa Monica, I saw an elderly man chastise a young woman for not wearing a mask. The woman flashed him an angry look. “If you’re so worried about getting COVID,” she yelled, “then stay home!” I was shocked not just by the rudeness of her comment, but by the fact that she was advertising how little she cared about the health of those more vulnerable than her or about our children’s ability to go back to school any time soon. My God, I thought, we’re not in this together. The social contract is breaking.

¤

What does mourning look like when the dead number 100,000? Elected leaders quickly turned to war metaphors. Doctors and nurses were said to be “heroes” and “warriors,” who were fighting “on the front lines” against an “invisible enemy.” More American lives were lost to COVID-19, reporters pointed out, than in the wars in Korea and Vietnam combined. But not even that grim statistic could really shake the national mood, which was concerned with forgetting. On Memorial Day weekend, videos circulated on social media of throngs of people partying at bars and restaurants at the Lake of the Ozarks or surfing and sunbathing at beaches in Florida.

Meanwhile, Trump spent his days fighting with the press and social media companies whom he perceived to be biased against him. Congress approved trillions of dollars in stimulus funds that went for the most part to corporations, which only three years earlier had received the biggest tax reduction in history. Facing budget deficits, governors and mayors warned of apocalyptic cuts that would affect schools, hospitals, libraries, parks, and other community services. Eric Garcetti, the mayor of Los Angeles, called the city’s forthcoming budget “a document of our pain.”

But who was in pain? Despite the mayor’s use of the plural pronoun, the pain did not afflict everyone. The Los Angeles Police Department, an institution known nationally for how it handled the Watts rebellion, the Rodney King beating, and the 1992 Los Angeles uprising, receives more than $3 billion per year. Its budget dwarfs what the city spends on health, education, parks, libraries, and community services, a disparity that is mirrored in many other police departments across the United States.

One moment that made the nation pay attention to pain was the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man, bought cigarettes from a convenience store on the evening of May 25, paying for them with a $20 bill that a clerk suspected was counterfeit. After police officers arrived, they put Floyd in handcuffs and dragged him onto the pavement, where Officer Derek Chauvin kneeled on his neck. The anguish that Floyd felt can be heard in his voice. He told the officers 16 times that he couldn’t breathe, called for his mother, asked for help, begged them not to kill him. Yet for eight minutes and 46 seconds, Chauvin kept his knee where it was, his hand casually thrust in his left pocket as he talked to the other officers. The killing, captured on cell phone video, was seen by millions of people in quarantine.

What is not visible to the eye is that Floyd had tested positive for COVID-19. In June, a post-mortem swab revealed that the virus was still present in his body at the time of the killing. So the government had failed him twice: it could not prevent his infection and it sent an armed agent who tortured him until he died. COVID-19 is new and perhaps, yes, unprecedented, but the killing of George Floyd was wholly precedented. It was part of a pattern of state violence against Black people and people of color, a pattern that not even a pandemic could delay or disrupt. The day after the killing, protests erupted in Minnesota, then spread to all 50 states. This is an indication that the pain of racism has, at long last, become intolerable.

Pain is a signal, my doctor once told me, when she chided me for taking so long to get the symptoms of an infection checked. Pain should not be ignored. Scrolling through my social media timeline in June, all I saw was pain. In Buffalo, police officers knocked over an elderly protester and cracked open his skull. In Indianapolis, they groped a woman and beat her when she resisted. In Los Angeles, they shot a rubber bullet in the face of a homeless man in a wheelchair. In Columbus, they maced a disabled protester and took off his prosthetic legs. In Louisville, they shot and killed a bystander. The brutality came in unrelenting waves.

Yet the pain was not treated; it was only exacerbated. As I write this, federal troops have been called to Portland, Chicago, and other major cities. The number of American fatalities has now passed 150,000. California, which reopened too many businesses too quickly, is back on lockdown. Everyone I know is slowly coming to terms with the fact that most schools, colleges, and universities will not reopen this fall.

¤

What are the signs of a good government? In 1762, Rousseau argued that, while there are many subjective criteria to evaluate whether a people are well or badly governed, only one measure was truly objective: the “protection and prosperity” of the people. All other things being equal, he wrote, the government under which citizens “increase and multiply most” is the best, while that under which “the people diminishes and wastes away” is the worst.

Under that criterion, the United States is undoubtedly failing. Six months into the pandemic, the president continues to treat the virus as a matter of personal responsibility, governors change plans every week, and public health measures like masking have turned into partisan squabbles. Rather than a nation, the United States is becoming an aggregate of 300,000,000 individuals who share the same land, but pursue private interests.

This fall, we the people are expected to educate our own children and, with or without jobs, pay for housing, food, and health care. Those who can afford to do all this can live safely; those who can’t will have to risk infection and death. Unless government and citizens honor their commitments in the social contract, the mortar that holds the blocks of the nation together will dissolve for good.

¤

¤

Featured image: "Man Displays American Flag On His Walker While Wearing Protective Face Mask In New York City COVID19 Quarantine" by Anthony Quintano is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Banner image: "bIMG_1374" by Becker1999 is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

LARB Contributor

Laila Lalami was born in Rabat and educated in Morocco, Great Britain, and the United States. She is the author of four novels, including The Moor’s Account, which won the American Book Award, the Arab-American Book Award, the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction. Her most recent novel, The Other Americans, was a national best seller and a finalist for the Kirkus Prize and the National Book Award in Fiction. Her essays and criticism have appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Washington Post, The Nation, Harper’s, the Guardian, and the New York Times. She has received fellowships from the British Council, the Fulbright Program, and the Guggenheim Foundation and is currently a full professor of creative writing at the University of California at Riverside. She lives in Los Angeles. Her new book, a work of nonfiction called Conditional Citizens, was published by Pantheon in September 2020.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Timeline, Flattening: Everyday Life in a Pandemic

Living through a quotidian catastrophe, one desperate text at a time.

Owning the Asphalt

Joseph Giovannini praises the protestors who took back the streets from the Landlord-in-Chief.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!