Noir for the Anthropocene: On Elspeth Barker’s “O Caledonia”

Chelsea Jack Fitzgerald reviews Elspeth Barker’s “O Caledonia,” a Scottish noir interested in the connections between different types of anthropogenic damage.

By Chelsea FitzgeraldDecember 26, 2022

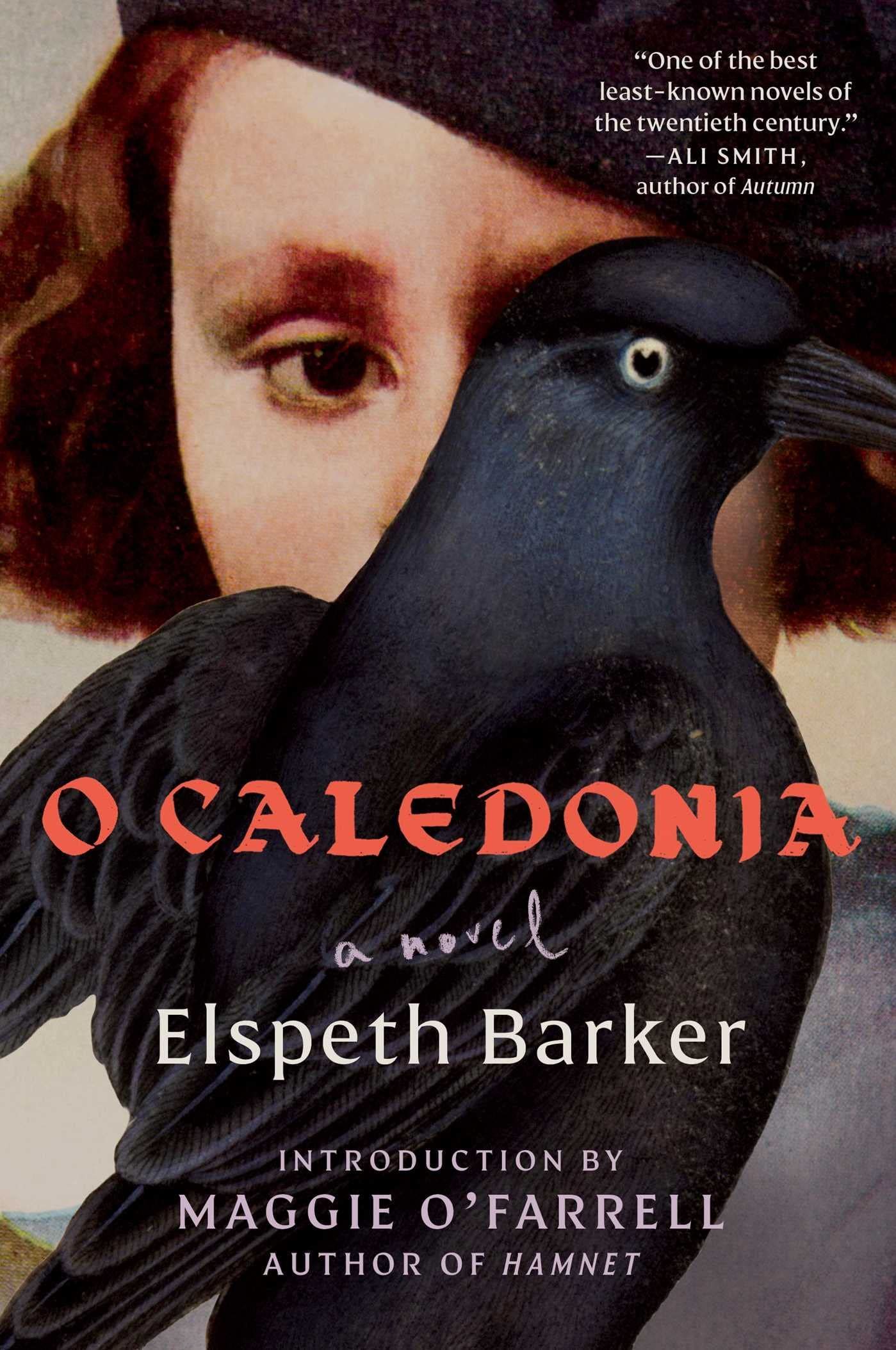

O Caledonia by Elspeth Barker. Scribner. 208 pages.

“WE BEGIN with a corpse,” Maggie O’Farrell writes in her introduction to Elspeth Barker’s newly reprinted 1991 noir novel O Caledonia. Barker’s first and only novel set in postwar Scotland — dubbed “one of the best least-known novels of the 20th century” by author Ali Smith — was recently republished by Scribner just months after the author’s death.

However, O’Farrell overlooks something important, or rather someone important, in her opening line. We don’t begin with a corpse — we begin with two: a teenage girl and a bird.

Janet, our young, chronically misunderstood protagonist who loves books and, above all, animals, has been found dead at her family's neo-Gothic castle, Auchnasaugh, in rural Scotland. The church on the moors has no room in the family plot on such short notice. Janet’s parents are secretly relieved: “Her restless spirit might wish to engage with theirs in eternal self-justifying conversation or, worse still, accusation. She had blighted their lives; let her not also blight their deaths.”

The people closest to Janet move on, but not her bird, Claws. Years prior, Janet had found the tiny bird grievously injured as a nestling. His beak was crossed and he had been “flung to the ground to die.” She saved his life, and in return, Claws became her lifelong companion. After her death, Claws is beside himself. No one notices his grief: “At last, in desolation, like a tiny kamikaze pilot, he flew straight into the massive walls of Auchnasaugh and killed himself. Janet’s sisters found him, a bunch of waterlogged feathers in a puddle.”

In what follows, Barker offers a haunting if bleakly funny account leading up to Janet’s murder and Claws’s death.

I doubt Barker would be surprised if we overlooked Claws, the second corpse. Human disregard for nonhuman life is one of the most prominent themes in her novel. Far from the usual whodunit, O Caledonia tells a story about an unforgiving if devastatingly beautiful world where some lives are valued over others: humans over animals, men over women. In such a world, things don’t end well. This unsettling novel pushes readers to imagine how things could be otherwise, but makes no false promises of redemption.

¤

After a cold opening, the novel travels back in time through the brief but intense life of a girl named Janet who, like Barker, moved with her family to a remote Scottish castle shortly after World War II. Lines between Barker’s life and her fictional protagonist’s run throughout the novel; both attend an all-boys preparatory school established by their parents and cope with social ostracism by turning to the company of books and animals.

Of course, the parallels come to an end: Barker led the literary life that Janet might have if not for her untimely demise. In her twenties, Elspeth (then Langlands) clerked at a London bookstore before meeting the poet George Barker. The two became a couple and were known for hosting writers, artists, and parties at their countryside home in Norfolk. Throughout her life, she taught creative writing and classics, having studied foreign languages like Janet. She was 51 when her first novel was published. The book received critical praise and multiple British literary awards before its popularity faded. She continued to write, contributing to The Independent and the London Review of Books, but O Caledonia remained her sole novel when she died at 81.

Imaginative and animalish

,

Janet struggles to gain acceptance in the “flawed and cruel” world of humans. To get by, Janet seeks shelter in the nonhuman world, riding bareback through the woods and on the wild moors near her home at the castle. Animals, which she loves “without qualification,” give her comfort. She finds it bewildering that their worth (much like her own) goes so unrecognized: “Everywhere there was hideous cruelty to animals. Once as she rode past the sawmill she saw a deer hanging in an open-sided lean-to. They had chopped off its head and its legs to the knee.”

In this postwar era, maimed soldiers haunt the streets; her parents force her to attend church services led by a fire-and-brimstone minister who sermonizes about the wrath of God, with no mention of love; and Janet’s father makes it known that “a girl was an inferior form of boy,” though boys and men act in ways that hardly warrant this elevated status. Take Jim, the gardener: “Jim’s face was darkly murderous. Janet had seen this look when he was clubbing the myxomatosis rabbits and stuffing them into a sack.”

We are meant to see Jim as a villain, but here Barker also smuggles in an ecological critique of human interventions in his violent actions. In the mid-20th century, humans intentionally introduced the myxoma virus in the United Kingdom to control rabbit populations, but the virus became less lethal over time. It began to physically harm the rabbits — sores appeared around their ears and eyes, and some went blind — but it did not always kill them.

Janet intervenes in the lives of nonhuman beings too, but often as an advocate against their mistreatment by humans, usually men who also abuse women. When her mother Vera’s loathsome friends, the Dibdins, visit, their son Raymond attempts to sexually assault Janet. She chooses to overlook this, but then Raymond goes too far by also threatening her cousin Lila’s cat. In an act of multispecies solidarity, Janet pushes Raymond into the poisonous tendrils of a Heracleum giganteum plant, which renders him incapacitated and unable to harm anyone.

There is another level of poetic justice here, insofar as Raymond had previously insulted this same plant — which Janet adores — by calling it a “really pernicious weed” and opining that Janet’s father should eradicate them. Janet and Heracleum get collective justice by thwarting Raymond, who disdains the lives of women, animals, and plants alike.

¤

What kind of consideration do we owe nonhuman beings? Utilitarian philosopher Peter Singer famously — and controversially — asked this in his 1975 book Animal Liberation. In it, he argues against “speciesism,” the idea that human life has greater sanctity than nonhuman life. We owe equal consideration and humane treatment to animals, he says, because they can suffer and experience pleasure. The next part is where things get dicey. He points out that some animals are more cognitively capable than some humans, and yet we value the lives of those humans without question. Singer attributes this bias to speciesism, which he compares to racism and sexism. If we believe the lives of severely disabled people are worth protecting, he asks, then why not animals?

“It is easy to see where this logic can lead and why so many disabled people regard Singer as, well … scary,” disability scholar Sunaura Taylor says. We need a vision of multispecies solidarity, she argues, one that refuses to value nonhuman life by devaluing the lives of some humans. Taylor sees disability and animal rights as connected, insofar as ableism has oppressive consequences for both groups. Humans justify eating animals because they do not endow animals with the same abilities to experience suffering. Likewise, when social structures or attitudes lead a disabled person to feel less than, or merely tolerated, that signals ableism.

O Caledonia approaches multispecies solidarity by identifying how seemingly different groups experience like forms of oppression. For example, Barker repeatedly draws attention to manmade disabilities. In addition to maimed soldiers, we see how human actions disable both the myxomatosis rabbits and Claws, who, disfigured, was flung to the ground to die. Janet “worried about his crossed bill,” and if he would ever learn to feed himself. As he healed, “she was glad to see that his damaged beak was only a slight handicap. He could fend for himself.”

Likewise, women and animals are both forced into captivity. In one chapter, Janet’s mother exiles Cousin Lila — a strange but harmless spinster who lives with them but prefers whiskey and, like Janet, the company of animals — to an asylum called Sunny Days. (Taylor might rejoin here that ableism makes it possible for Vera to have Lila categorized as mentally deficient and confined in an asylum.) Later, Vera takes her children to the zoo, where she insists the animals have “some freedom” despite the enclosures. “Janet stood watching the monkeys. How dispiriting to think that these were close relations.”

We also see multispecies solidarity when human and nonhuman characters negotiate oppressive conditions together. Janet cares for animals, but animals also care for Janet when people fail to do so. Her father believes that girls can only overcome their natural inferiority to boys through education. “For this reason he had started a boys’ school for his daughters to attend.” The only girl at the school, Janet attempts to “prove her worth” by climbing a tree. From the ground, her male peers tease that they can see up her skirt. Distracted, Janet falls. She comes to with her mother standing over her, accusing her for having “no sense.” Janet seeks refuge in the horse stables, where she finds her faithful pony, Rosie. “Here was comfort, here was communion.”

The novel recommends multispecies alliances because membership in the same species does not guarantee solidarity. Vera proves no more inclined than Janet’s male peers to support her daughter’s aspiration to prove her tree-climbing bona fides. Men fail to support women, but so too do other women.

¤

“In noir, everyone is fallen,” novelist Megan Abbott has observed

,

“and right and wrong are not clearly defined and maybe not even attainable.” For this reason, noir feels uniquely suited to explore complex systemic problems, such as gender inequity or disregard for the nonhuman world, where the origins and responsibility for a given problem are often as obfuscated as they are widely distributed. We know this genre not by seeing one obvious villain, but by breathing in its villainous atmosphere. Everything, rather than something, is wrong. Abbott continues, “In that sense, noir speaks to us powerfully right now, when certain structures of authority don’t make sense any longer, and we wonder: Why should we abide by them?”

Janet refuses to abide. She questions, for example, why she should like babies or enjoy taking care of them on account of her gender. She resents being gifted a doll and pram because the adults expect her to “trundle about like a little mother.” Instead, she converts the pram into a chariot for her cat. Together, they turn this symbol of feminine compliance into a “stinking ossuary of parched bones mingled with fur, feather, and the sullen reptilian sheen of rats’ tails.” Likewise, when she rescues Claws, Janet turns an otherwise offensive dollhouse into a shelter for him: “At last it had a purpose.”

Janet questions the ethics of bringing more human life into the world. She notices that humans often do more harm than good, especially toward animals. Her actions suggest that humans should first try to do better, toward one another but also towards animals, before increasing their presence.

Janet models “wakefulness” in a damaged world. Philosopher Thom van Dooren has used this term to describe a way of paying attention to disappearing forms of life in the Anthropocene, an epoch shaped by the disproportionate and often devastating impacts of humans on the planet, including climate change, but also biodiversity loss and mass extinctions.

When I say that Janet models this kind of wakefulness, I am thinking of a scene where she buries a squirrel that was struck by a car. This is one of several animal burials in the novel. She can only find a gardening fork but proceeds to digging anyway:

Suddenly on the prong was a frog, transfixed and splayed, kicking wildly. Janet’s heart lurched. “O son of man,” she gasped. […] She buried the squirrel and then she sat by the small grave and was overwhelmed by grief. […] It seemed to her then that the nature of Caledonia was a pitiless nature and her own was no better.

Individual cars often prove fatal to people and animals like squirrels, but this reference also invokes fossil fuels and a burning planet. At this point, even well-intended human actions may be too little, too late.

O Caledonia makes it unclear how, and if, humans can repair a damaged world. That mystery of the novel remains unsolved even after we learn who killed Janet. However, Barker suggests that there is no hope if humans persist in overlooking the second corpse.

¤

LARB Contributor

Chelsea Fitzgerald is a PhD candidate in anthropology at Yale and an assistant editor at The Yale Review.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“A Story Is Always a Question”: On Ali Smith’s “Companion Piece”

Smith’s new novel tests what a “pandemic novel” and a “pandemic author” might be.

Closeness and Cruelty: On Tana French’s “The Searcher”

Glenn Harper hunts down “The Searcher,” the latest thriller from Tana French.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!