Multilingual Wordsmiths, Part 3: Edith Grossman on Reading Spanish and the Pitfalls of Literalism

"Translations aren’t made with tracing paper — two languages do not fit into the same space at the same time."

By Liesl SchillingerMay 26, 2016

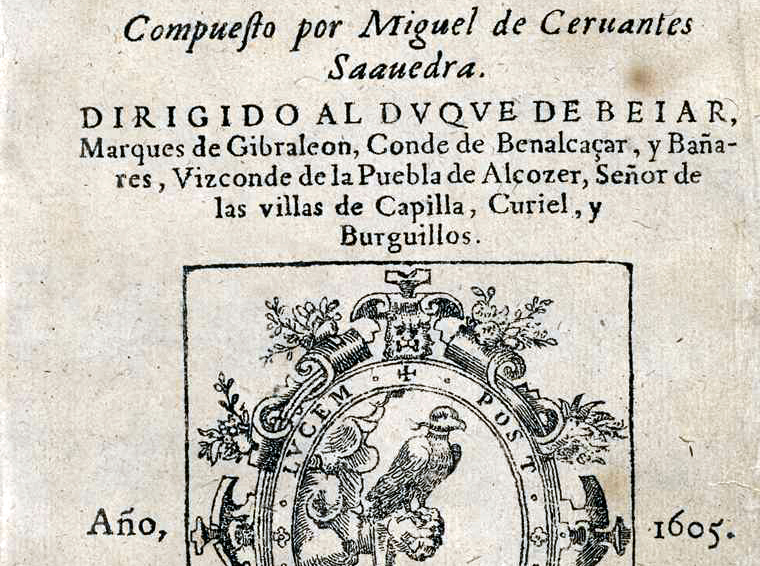

IF YOU ARE AN ENGLISH speaker and you have read Love in the Time of Cholera, by Gabriel García Márquez; or The Feast of the Goat, by Mario Vargas Llosa; or the poetry of Luís de Gongora, Ariel Dorfman, or the visionary Mexican nun Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz; then chances are you have read these works in English, not Spanish, through the supernally well-calibrated filter of Edith Grossman’s translation. Some of the other highlights of her half-century of sterling creation include another Spanish novel you may have heard of: Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote. In her stirring nonfiction book Why Translation Matters, Grossman explains that this intricate art and vocation “helps us to know, to see from a different angle, to attribute new value to what once may have been unfamiliar.” She writes, “The alternative is unthinkable.” And yet, when Grossman was a girl in Philadelphia, it was not necessarily thinkable that she would grow up to become one of the world’s most gifted, revered translators of Spanish. In her household, English was the only language spoken — sprinkled with a liberal dash of Yiddish and a light peppering of Hungarian. In our conversation, she retraces the origins of her love affair with the Spanish language, revisits her proudest literary milestones, and explains that “the writing of a translation is an intuitive act as well as a linguistic act.”

¤

LIESL SCHILLINGER: Did you grow up multilingual?

EDITH GROSSMAN: I grew up something-lingual; I was basically an English speaker, but when my parents wanted to say things so I wouldn’t understand, they spoke in Yiddish, then my mother when she got very angry would curse in Hungarian; but I never quite understood what they were saying. I did know some Yiddish words because I grew up in a Jewish neighborhood in Philadelphia. The only time I ever spoke Yiddish was when I was in Istanbul, and the cab driver spoke German, and I spoke Yiddish, and we managed to figure out where to go and how much it cost. But I guess the real answer was I grew up monolingual.

From what languages do you translate?

Only Spanish.

What drew you to the Spanish language?

In my checkered career as a student before college, the only teacher I could tolerate was my Spanish teacher in high school, so I decided whatever she did I was going to do. That was in Philadelphia. I majored in Spanish in college, and I did my graduate work in Spanish and Latin American Literature. I went to the University of Pennsylvania, and then I was at UC Berkeley for a couple of years, and then I earned my PhD at NYU.

What made you decide to start translating?

In a way, it wasn’t my decision. A friend of mine, Ronald Christ, edited the magazine Review, that used to be published by what is now called the Americas Society. Ronald asked me to translate a story for the journal, and I said, “Ronald, I’m not a translator, I’m a critic, “and he said, “You call yourself whatever you want; just translate the damn piece for me.” It was a piece by an Argentine, Macedonio Fernández — he was in the generation before Borges, he was Borges’s father’s age, and he was probably the most eccentric writer and man I have ever run across in my long career. He wrote astounding stuff, and as it turned out, my translation was the first prose piece of his to be translated into English — I didn’t even know that at the time. I think it must have been the early 1970s. The piece was called The Surgery of Psychic Removal, which was a surgery that could remove eight minutes of memory.

Ah, like in the movie, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind?

Yes! I mean, it is very bizarre, very funny, but not really funny — it is creepy to have your memory excised. I started to translate more and more, and I discovered I really enjoyed it, and I could work at home, which is my favorite place to work, so I did it more and more over the years. I was moonlighting as a translator, but my sunlight job was teaching at colleges. I taught at NYU at various campuses, on CUNY campuses, and at a small Catholic college upstate called Dominican. Then one day, I decided to quit teaching and to translate full time, and one of my editors at Knopf asked me, “You really can live on what you earn as a translator?” I said, “I have 2001 recipes for beans, so it will work out.” I still teach now, but only one class a year at Columbia. I love teaching — I just don’t like being a full-time academic. I love being in the classroom, I really do, and I’m teaching the MFA in creative writing.

How did you come to translate Gabriel García Márquez?

Knopf called me and asked me if I would translate García Márquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera. I think it came out in the late 1980s or early ’90s. It opened a lot of doors for me. I already had been translating for a lot of years, but when that novel was so successful, and I was recognized as García Márquez’s translator, that was a wonderful moment for me professionally and personally.

What do you like about translating?

What I love most is that it gives me a chance to write every day, and I never face a blank page; I always have a page filled with words. Also, I really find out the bones of an author when I translate his or her work. When I read as a general reader, I say, “That was really good”; but if I translate it, I say, “Oh my god, this is utter genius.” I’ve always felt that.

Do you write fiction?

No. Every time I tried, it condensed down into a poem. I’ve tried fiction, and I can’t do it.

What do you not like about translating?

You mean sitting at computer and having aching fingers? That my back hurts a lot? Sitting so much is difficult; you have to get up every hour. There are times when I’m translating seven days a week. When I was younger, I was doing seven hours a day, but now I’m down to five. I just finished the collection of Cervantes’s novellas; he has 12 of them, and the last time the complete collection was published in English was 1885, so it is as if they had never been translated before. The book is called Exemplary Novels. And I’m currently working on a wonderful novel by a man named Carlos Rojas, who is a Spaniard but lives in Atlanta. It is difficult to explain because of the fantastic elements, but it’s called Valley of the Fallen, which is, you know, the monument Franco built to himself and the Spanish fascist dead after the War, by the Escorial. Philip II built the Escorial — a monument to Catholic Spain — and Franco followed suit with the monument to fascist Spain. The main character is an art historian who coincidentally is named Vasari, and he is writing about Goya; I can’t quite remember how it works in the book, but what eventually happens is there’s a confusion between Franco and Ferdinand VII, who was the worst and most reactionary of the monarchs restored after the Napoleonic Wars. There was a whole generation of romantic poets who wound up in England because they couldn’t stay in Spain, it was such an oppressive regime.

Do you have a favorite of your translations?

I’m really very proud of my Don Quixote. Then the poetry of Luis de Góngora. I did his book The Solitudes, which is probably the most difficult poem in any language. And I also did some of his shorter poems and sonnets in an anthology.

I read that Gabriel García Márquez said he preferred your translations to his originals.

He was a very kind man, he told the same thing to Gregory Rabassa. [Rabassa translated García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, among other works by the author.]

What do you like about translating the work of living authors?

The advantage of translating a living author is that you can ask him or her questions. But I don’t do that until the very end. I really leave them alone, because my feeling is, once they’ve written their book, they’re finished with it, they’re on to the next one, so what I’m asking them pulls them back to a work they have already completed and wish they could be done with already. I talk to them at the very end, and ask them to clarify what their intention was in places in the book that I’m not sure about.

When translating a previously translated book, do you consult prior translations?

I never look at the other translations, I don’t want to have another translator’s voice in my ear, I want to confront the text on my own.

Is this different from Lydia Davis? She told me you and she once had different approaches.

The Paris Review published a dialogue between her and me, and we take entirely different tacks. I think at some point she read every translation of Flaubert she could get her hands on. I feel the opposite: I don’t want that other voice in my head.

I see; actually, Lydia Davis told me she does not look at prior translations while working on her own. If she looks at them, it’s only afterward. Do you look at the other translations afterward?

The answer is no. It took me roughly two years to translate the Quixote, and after I finished Part One, I thought I could start to look at other translations and use them as dictionaries — my kids had left schoolbooks at my apartment. But every time I consulted two different translations of the word that was giving me difficulties, their translations were different, so they were of no help to me at all.

What about reading the book you are translating ahead of time? Lydia said she doesn’t but thinks you used to. What is your process?

It kind of varies. I have done books the way she did, and have begun to translate them before reading them. Sometimes it’s a matter of time and deadlines. Reading a book takes some time, and I’d rather put the time into translating it. In early drafts, the beginnings are usually the weakest part of my translations, I feel. Whatever is wrong comes at the beginning, when I’m not really sure what the voice should be yet; I find out as I’m working on the book. There are many drafts — more drafts than I care to count.

I translate as carefully as I can for the first draft, because the more care I take in the beginning, the less time I have to spend at the end doing revisions, but I’m a professional revisor — I always second-guess myself — so I do the best I can on the first draft and when I go back, it’s never good enough, so I revise at least two or three times, then when I send it in, I get back the copyedited version, and it keeps going on until they say it’s done.

Do you read the books you have translated, after they are out?

I try very hard not to read my books, but if I happen to be teaching them, I have to read them. But I wouldn’t read them for fun.

What makes a good translation?

It is how comfortable the translation is in English, if we’re talking about translation into English. There is something called “translatorese,” which is a made-up language that doesn’t exist in the world. There’s a wonderful cartoon that has a picture of a very unhappy writer and a very bewildered translator, and the caption says: “Do you not be happy with me as the translator of the books of you?”

What makes a bad translation?

Literal word-for-word, getting trapped into the literalism of thinking you’re being more accurate or more faithful if you do that, and of course you’re not. Translations aren’t made with tracing paper, and two languages do not fit into the same space at the same time, so there are adjustments and changes you have to make to turn one language into another language.

Why should English speakers read works in translation, what do they get out of reading novels from foreign cultures?

If we don’t, we are cutting ourselves off from most of the world. English is a dominant language these days, but not everybody in the world writes in English, and we tend to be rather parochial about translation. I think if you were to speak to editors in New York, you’d find the foreign languages they know would include Spanish and French, maybe some German, maybe a little Russian, and then everything else is exotic, and we tend not to have any contact with the cultures and literature of those languages. We do ourselves great harm if we don’t read what the rest of the world is writing.

Do you think translators get short shrift in the literary world, and if so, is that changing?

I do think they get short shrift; it was a great struggle for me to get my name on the cover of a book, because American publishers did not want the public to know that the book they’re picking up is a translation. They had this idea that Americans were not interested in reading translations, so they wanted to somehow hide the fact that it was a translated book. Very early on, I started to use a lawyer to negotiate the contracts. As I tell my students, when you’re signing a contract with a publisher, you’re signing a contract with a corporation, and they have offices filled with lawyers, so before you sign a contract, you have to hire a lawyer who can interpret the legalese. The legalese is intended to obfuscate; it’s not intended to be understood by ordinary people.

What is your title, apart from translator?

I teach writing up at Columbia, I’m an adjunct professor in the translation section of the writing division, and I have students who are interested in translating.

Are there translation BAs these days?

When I was coming up, there was no such a thing as a course in translation; these days more and more universities have translation studies, whether or not you can get a degree in them.

Do you feel optimistic about the future of translation?

It depends on how I’m feeling, on a given day. When I feel there is a future for fine writing, a future for fiction and poetry, I think that carries translation along with it. But on days when I think nothing that is not an electronic image will be of interest to anyone in 10 years, then I think it is the end of literature. It depends on which day you catch me.

How many books have you translated, roundabout?

Somebody told me the other day it was 60, but I don’t know if that’s true. I’ve been doing it a lot of years.

Which of your translations was the greatest pleasure to work on?

I will go back to Don Quixote, which I think is the best damn novel that’s ever been written in any language in any century — anything that Cervantes touched he turned into gold. He’s a remarkable genius; he defines things the way Shakespeare defines things for us. You can’t think of theater without having Shakespeare’s plays come to mind, and Cervantes is similarly important for the novel.

Have you translated woman authors?

Oh yes! One is Mayra Montero. She is a wonderful writer; she is Cuban-born and lives in Puerto Rico. I’ve translated six or seven of her novels. And Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, a 17th-century Mexican nun, who was a poet. She has written some spectacular sonnets and other poetic forms. She has a very long poem, comparable to Luis de Góngora’s Solitudes, called First Sleep. It is very difficult but very gorgeous poetry. She was a self-taught and brilliant woman and she knew a great deal about music and mathematics and science. She entered a convent in her late teens, but at some point, the bishop of Puebla attacked her in writing, wrote a letter pretending to be a nun, saying: Isn’t it too bad that a woman of talent is wasting her time on secular matters, when there is the Bible to look at? Sor Juana wrote an answer which is a very famous document in the history of feminism: she defends a woman’s right to read, to write, to study, to teach, and to use her mind. She said, and I’m paraphrasing: “Her mind is not an act of her will, it’s a gift from God and it’s not anything you can deny.” Then she said that there is no way you can read the Bible without a background in secular knowledge. It is stunning — she goes through various moments in Biblical literature, where you cannot understand what’s being said unless you know mathematics and music. You have to read this, Liesl: it’s a wonderful document. The upshot, of course, was that she was chastised and forced to sell her library — they estimate she had the largest library in Mexico — and she was forced to stop studying and give up everything in her life. She really was a pioneer.

Can you complete this sentence: A translation is to the original as X is to Y.

The relationship between the translation and the original is the connection between the mirror image and the living body. Cervantes spoke about translation in Quixote; he said reading a translation is like looking at a tapestry from the back, you see all the hanging threads. I think the writing of a translation is an intuitive act as well as a linguistic act.

Who’s a Spanish author people aren’t reading but should be?

Carlos Rojas, who I think is a stunning novelist. He has written a great deal in Spanish. Besides Valley of the Fallen I’ve translated one other book of his, The Ingenious Gentleman and Poet Federico García Lorca Ascends to Hell — the “ingenious gentleman” is what Cervantes called Don Quixote. I think Rojas should be much better known than he is. He’s highly imaginative, very original, and immensely smart, and he’s still alive: a living author, right in our own country.

¤

Liesl Schillinger is a New York–based critic and translator.

LARB Contributor

Liesl Schillinger is a New York–based critic, translator, and moderator. She worked at The New Yorker for more than a decade and became a regular critic for The New York Times Book Review in 2004. Her articles and essays have appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Daily Beast, The New Yorker, Vogue, Foreign Policy, The New Republic, The Washington Post, and many other publications. She translates fiction and nonfiction from German, French, and Italian; recent novels translated include Every Day, Every Hour by Natasa Dragnic (Viking), and The Lady of the Camellias, by Alexandre Dumas, fils (Penguin Classics). She is the author of the book Wordbirds, an illustrated lexicon of necessary neologisms for the 21st Century (Simon & Schuster).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Multilingual Wordsmiths, Part 2: Michael Hofmann in an Age of Increasing Insufficiency

Michael Hofmann and Liesl Schillinger discuss knowing German and translating the big story.

Multilingual Wordsmiths, Part 1: Lydia Davis and Translationese

I enjoy that aspect of writing that doesn’t involve writing one’s own things; I also love the puzzle aspect of it. Translation is writing and a...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!