Modern-Day Oracles: On Alice Wong’s “Year of the Tiger: An Activist’s Life”

Laura Mauldin reviews “Year of the Tiger: An Activist’s Life” by Alice Wong.

By Laura MauldinSeptember 15, 2022

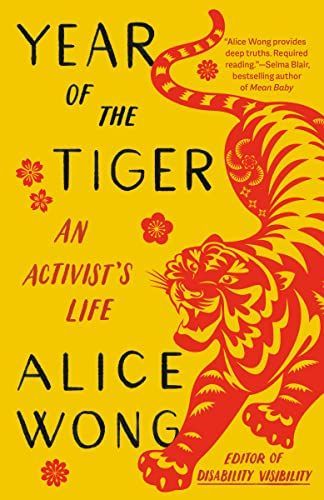

Year of the Tiger: An Activist’s Life by Alice Wong. Vintage. 400 pages.

IN EARLY 2020, Dan Patrick, the lieutenant governor of Texas, openly said that the elderly or infirm should simply sacrifice themselves so the economy could stay on track. Another official in California suggested letting the virus run its course on “the sick, the old, the injured” in order to “fix” society. Over the next two years, leaders ultimately settled on a strategy not dissimilar from these statements, making COVID-19 every individual’s problem and risk assessment, rather than a collective effort where we took precautions to protect those most at risk. All of these responses reveal how the United States casually dismisses disabled people as disposable and how this violent sentiment is deeply embedded in bureaucratic policies and translates into state neglect.

If you have been paying attention to disability politics in the United States, you likely already know of Alice Wong because of her central role in disability culture and activism. Whether or not you already know of her, her latest book, Year of the Tiger: An Activist’s Life, offers a deeper glimpse of who she is, as well as a righteous and powerful vision for the future. To do so, it grounds us in her life, but also in the broader politics of disability. To make a better future, she digs into her life and her encounters with the world in trying to get care, to receive an education, and to stay alive. She makes clear that the US pandemic response is just one more example in a long history of state indifference to disabled people’s lives. She illustrates this by talking plainly about such things as her daily care needs and homecare services, and her experience navigating what social safety nets the United States does have (in a recent essay since writing the book, she points out that the nets are not a net all, but rather “a big fucking hole”). One of the many things Wong does well is talk about complex and daunting systems and policies in a way that drives home for the reader just how inadequate and cruel our social safety nets are, while effectively conveying the stakes so we all know the importance of what she is trying to tell us.

And it is important. A quarter of the US adult population is disabled and half of us live with a chronic condition, and yet we act as if disability is rare and that disabled people don’t matter. And this is where Year of the Tiger storms into the room and talks directly to disabled readers: “[B]ecause at the end of the day no one will remember and save us except us,” Wong says. “That requires community. And this community will save us.” It is a particular skill that Wong has: she is at once brilliant and accessible — a storyteller above all — and a leader who knows she has to say what needs to be said, and then rest. That is, although the politics of the pandemic certainly show up in the book, Year of the Tiger makes sure that we know that conversations about disability have long been happening, so take heart because there is a long history of disability communities taking care of each other, and a long arc to her activism too.

Year of the Tiger is Wong letting us into her life a bit, and frankly, I often felt I was reading a serious text that felt like a visitation, but also one that knew how to be fun and whimsical. This is because the topic is deadly serious, but Year of the Tiger is an eclectic mix of materials. It includes original essays, but it is also a scrapbook-style compilation of recipes (spinach and mushroom soup), lovingly described meals (money dumplings on Lunar New Year), drawings and mottos (“Fuck You, Pay Me”), photos (her cat), transcripts of podcast conversations, and reprints of previously published pieces. Wong knows how to pull together a variety of sources and cultural artifacts, alongside much-needed moments of levity to get us through.

In the original essays, she takes us on a tour of her childhood, the festivities and beauty in her immigrant Chinese family and community, all while incisively breaking down why our current social context is ableist, and outlining the social change we still need. In pulling together various other essays she has published across many venues, the book is a constellation of different types of writing, rather than a linear narrative. Indeed, it includes various podcasts or other types of interviews that sometimes describe the same events, albeit each time a little bit differently. Seeing her tell her story in different ways was like a writing prompt that has you retell your story to different people, each time yielding different details. And I liked this because her life and mind was something I want to hold in my hand and look over, turning and turning again and again to see what new aspect I can find.

In piecing all of this material together, Wong has created a sprawling archive of her life and her activism. And on this point it is important to say that, most of all, this is a book written for disabled people. By sharing her life, inserting guidance to remember to eat, insisting on having boundaries and to rest, her book is a roadmap, a lovingly compiled book of tips and tricks for how to be disabled, how to guard your needs fiercely (see the drawing and motto: “Just Say NOPE”), and above all, how to keep going. She takes particular care to include a letter she wrote directly and specifically to disabled Asian American girls and women. “Shit is hard, right?” Wong says here, “Growing up and becoming more comfortable in our own skin is a tough, nonlinear process. I am still working on myself as I imagine you are, too.”

It is in this way that Year of the Tiger is also a radical act of care for its readers. Over and over, Wong encourages people to take care of themselves, to step away from the grind when needed. That is to say, Wong makes clear that we all must do the work to care for one another, but also insists on the importance of rest and on wrestling with the realities of our finite energies and fallible bodies. While much remains to be done to achieve disability justice, the need for both self- and collective-care existed prior to the pandemic and will continue well beyond. As such, Wong straightforwardly tells readers to know their limits, take naps, and eat. She will go into detail about some luscious delicious food, then remind you that she — and indeed all of us — have the option to use our autonomy to opt out sometimes. You can give and take your attentions as you see fit; her message to disabled people — who constantly face a barrage of demands to be “more” or “better” or to live up to some idealized notion of normal that one never can quite realize — is to rest, and, if they want, to see opting out sometimes as autonomy, as freeing. You don’t have to carry it all. Year of the Tiger is doing serious work — because her message, after all, is about the value of people’s lives, that they are worth living even in the face of a society that might tell you otherwise.

And I think, in following Wong’s example, that this is an important moment to pause and note just how funny she is. Perhaps cheeky is the better word. In one chapter, she talks about a food or eating treasure hunt, but the book is one too. Each page its own square in a box of treats; I felt like I was unwrapping a variety box of a memoir, constantly surprised and finding new ways into knowing her. The book has a collage feel, the aesthetic of a zine, mucking around in different aspects and ways of telling stories. She also candidly describes her toilet time, her struggles with gas. She’s not afraid to talk about pain or shame or the universal grossness of our bodies. She’ll move between this and linking it back to bigger things like issues around taking your time and getting homecare because everyone deserves that so they don’t have to be institutionalized. She’ll reflect on some deep ableist garbage and then say, “That’s some deep shit.” She’ll call you out, sort of gently, while saying fuck you (her motto is “Fuck the fuckers”). It bears repeating: Wong is as funny and whip-smart as she is serious and commanding. She knows how to wield levity when it is needed, and she also knows how to have boundaries. Year of the Tiger sets the terms and expectations for her visitation on this earth with us, pushing back on demands to constantly educate without being paid, and calling out the publication industry for its lack of disability representation. “Are memoirs by disabled people the zoo exhibit of the publishing world, allowing the reader (assumed to be a default white, nondisabled, cisgender, heteronormative person) to peer into a life they find equal parts fascinating yet unimaginable?” She will write her story, but she will not be reduced to a spectacle. Alice Wong is not going to take your shit.

Above all, Wong is a storyteller, and she shines in the essay form. “[E]ssays are my jam” she says, and “essay writing is my activist tool of choice, my peak creative and intellectual practice, where I layer, condense, finesse, and coax a thought into a Thing.” Indeed, the essay “About Time” is part existential meditation and part craft essay. The essay form lets her show us how to think about our life and its inevitable end. This comes through in her steadied approach to her own mortality in other essays like “Ancestors and Legacies” and the self-authored obit of sorts titled “Future Notice.” It is clear Wong is building on a thread in her work and life on the notion of disabled people as oracles. As she articulated early in the pandemic on her Disability Visibility Project site, “Disabled people know what it means to be vulnerable and interdependent. We are modern-day oracles. It’s time people listened to us.”

Alice Wong is here to dispel myths, explain the realities of disabled life, and light the way for the rest of us. Year of the Tiger is thus a bold and unafraid gesture towards assembling the parts of her life into something new, something bigger than herself, something that will go on when she is no longer here. I have had my fair share of experiences encountering religious texts while growing up in small-town Texas, but it has been decades since then. What I immediately remembered while reading Year of the Tiger was the rush that comes from the knowledge that you are about to be witnessed to. To co-opt some of that evangelical talk: Alice Wong is here on this earth for the moment, but she is not of it. And the oracle has spoken: “Slow or fast, people can find me in these words and the spaces in between long after I’m gone.” As conversations about disability become more heightened and ableism more clearly surfaced and perhaps confronted, Year of the Tiger comes at the perfect time to catalyze what comes next, offering a psalm for how to endure.

¤

LARB Contributor

Laura Mauldin is an associate professor at the University of Connecticut and author of Made to Hear (University of Minnesota Press, 2016). She’s currently writing a general-audience nonfiction book on disability and spousal caregiving that weaves together memoir, reportage, and cultural commentary.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!