Memory Work: Reading and Writing Japanese American Incarceration

Following the 80th anniversary of Executive Order 9066, Erin Aoyama reflects on the uses of Japanese American memory work.

By Erin AoyamaJune 9, 2022

I THINK A LOT about what it means to remember — and why it matters to remember. As a historian and as a descendant of Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War II, I wonder about how to hold and honor the gaps in my family stories while learning as much as possible about the forces that shaped the lives of my ancestors. What do we do with what we learn? How do we remember silence?

In very real ways, history — the stories that we tell ourselves about the past and our places within it — impacts how we relate to and take care of each other in the present. What new possibilities might arise if we were to consider history as ongoing memory work, rather than a set narrative of progress or as singular “truth”?

I define memory work, drawing from scholars, public historians, and community organizers, as a process of locating and listening to stories about the past, reckoning with how they shape our families and communities in the present, and then sharing these stories and our experiences within them with others. Memory work asks us to find grounding in our family stories and understand them as constitutive of a larger whole even, or perhaps especially, when the narratives we learn in school or see represented in mainstream media fail to include them. In short, memory work is a way of engaging with the past that impels each of us to action in the present. traci kato-kiriyama, a writer and activist whose 2021 book, Navigating With(out) Instruments, offers a beautiful guide to this kind of work, describes it as a way to “flay yourself open” in public, to create space for imagining and building futures rooted in justice, together.

Above all, memory work can shift us beyond thinking about what history is, to think instead about what history does — and might do. The history of Japanese American incarceration and its afterlives provides a powerful case study in memory work because it is a narrative riddled with both persistent silences and broad implications for today. This year, as we mark 80 years since the opening of the wartime prison camps, this case study proves especially timely. In the memory work of two Japanese American artists, kato-kiriyama and playwright Nikki Nojima Louis, we can see how history can be a foundational tool for building solidarity.

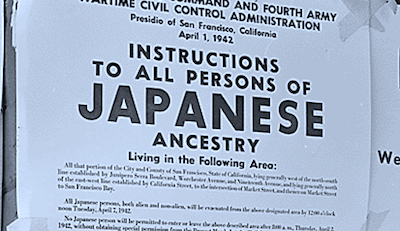

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which facilitated the mass removal and incarceration of more than 125,000 persons of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast. While ostensibly a response to Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor and the US entry into World War II, the order was also a culmination of decades of anti-Asian racism that had earlier fueled legislation like the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. Immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the FBI arrested Buddhist priests, Japanese language teachers, and community leaders, sending them to Department of Justice and US Army internment camps scattered across the country’s interior. Beginning in March 1942, all persons of Japanese ancestry remaining on the West Coast, regardless of citizenship status, were given fewer than 10 days to pack up their lives and belongings, sell what they could, and bid farewell to friends, teachers, pets, and farms. They took only what they could carry and boarded buses to fairgrounds and horse racetracks that had been hastily transformed into temporary detention centers. They did not know where they were going, how long they would be gone for, or if they would ever return home. After several months, they boarded trains to 10 prison camps — Manzanar and Tule Lake in California, Minidoka in Idaho, Gila River and Poston in Arizona, Rohwer and Jerome in Arkansas, Granada in Colorado, Topaz in Utah, and Heart Mountain in Wyoming. Beginning in 1945, Japanese Americans gradually returned to areas that had been their prewar communities. Some were able to return to businesses, homes, belongings, and farms. Others, especially among the older generation, never recovered.

Many Japanese Americans did not speak about their incarceration in the early postwar years, burying the shame, the fear, and the pain to rebuild their lives. In the late 1960s, drawing inspiration and intention from the Black freedom struggle, younger generations of Japanese Americans organized community pilgrimages to the sites of the former camps, trying to understand the silences and the trauma of their parents and grandparents. In 1976, Michi Nishiura Weglyn published Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America’s Concentration Camps, the first full study of the period written by a Japanese American. In 1978, a group of Asian American activists in Seattle planned a “Day of Remembrance” (DOR), an event whose invitation read, “Remember the concentration camps / stand for redress with your family.” In 1980, responding to decades of community organizing and political maneuvering, Congress established the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC), whose findings rejected claims of “wartime necessity” and instead cited “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership” as the reasons behind Japanese American incarceration. In 1988, President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, which granted a presidential apology and $20,000 to all living survivors of the camps and established a public education fund.

For Japanese Americans today, pilgrimages and DORs remain important annual events. February 19 each year is marked by remembering and activism, providing space for our community to think, together, beyond the bounds of our own histories. Through these intergenerational gatherings, more Japanese American elders have shared their memories of “camp” and its impact, recognizing that their testimony might help to spare others from similar traumatic experiences. This ongoing memory work shows that Japanese American incarceration was not an exceptional moment in American history. Rather, it is one example of state violence emerging from the combined forces of settler colonialism, capitalism’s demands for cheap labor, and the construction of national borders in the service of white supremacy. Situating memory work as a foundation for solidarity building means that we can honor our family stories while simultaneously de-exceptionalizing them. Rather than diminishing their power, this de-exceptionalizing places them in context and allows the reckoning at the heart of memory work to have an impact beyond the Japanese American community. We can see more clearly how our histories are tangled up with each other and, in that clarity, understand our futures as bound together, too.

In the wake of 9/11, Japanese Americans stood up in support of Arab and Muslim Americans to call out dangerous and racist measures put in place for “national security” that felt all too familiar. Around the 2016 election of Donald Trump, when the so-called “Muslim Ban” hit the airwaves, closely followed by news of ongoing ICE raids, deportations, and family separations, members of the Japanese American community again drew power from family stories to organize and protest. Tsuru for Solidarity, a group that formed in 2019 to protest migrant detention, used their demonstrations to draw explicit connections between Japanese American history and the present with slogans like “Stop Repeating History!” and “Never Again is Now.” Artist and writer Nikki Nojima Louis, a survivor of childhood incarceration and family separation, was on the front lines for Tsuru for Solidarity’s actions at Fort Sill in Oklahoma and Fort Bliss in Texas.

Louis was four years old when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. During the war, she spent over two years incarcerated with her mother, first at a temporary detention facility outside of Seattle, and then at Minidoka in Idaho. Her father, Shoichi Nojima, was arrested by the FBI and incarcerated in New Mexico. In 1985, Louis wrote her first play, a readers theater piece called Breaking the Silence. Readers theater plays are usually dramatic narrative readings with minimal to no staging; the actors rely on the script and their phrasing and expression to tell the story, allowing the audience’s imagination to fill in the blanks. Louis’s play stretched the bounds of readers theater, combining oral history fragments, tanka poetry, taiko drumming, and singing to narrate Japanese American history in many voices. At times, the show provoked laughter, especially from the predominantly Japanese American audience, at familiar accounts of arranged “picture” marriages where a young Japanese woman is disappointed that her husband is neither as rich nor as handsome as he had purported to be — humorous in the way that shared family roots and mishaps can be funny. At other times, Breaking the Silence was deeply vulnerable, laying out across a stage the hopes and the heartbreaks of a community.

Louis remembers one of the actors returning from intermission during that first performance to report that there were Japanese American men crying in the bathroom. These tears, striking for their challenge to the era’s investments in silence and capitalist notions of Japanese American “recovery,” demonstrated the power of the collage of memory and history in Breaking the Silence. Expressed quietly in public, the tears were admissions of pain and trauma that could no longer be covered over by the passage of time; as kato-kiriyama writes in Navigating With(out) Instruments, tears are “bits of truth coming up for air.” Breaking the Silence made space for reckoning with these bits of truth by insisting the audience sit with both grief and the nearness of the past.

Louis continues to tour with Breaking the Silence, which has evolved from its origins as a play meant to tell Japanese Americans a story about themselves, to a piece rooted in telling Japanese American stories in order to shed light on the continuity of history. Today, its performances focus on teaching about and remembering the wartime incarceration to show that the treatment Japanese Americans experienced is not only possible in the United States but ongoing. Every time it is performed, Louis can change which oral history fragments, photographs, and soundscapes are used. The staging, straightforward as it is, can be tweaked to highlight certain characters at different moments. Because of this flexibility, Breaking the Silence performs a kind of memory work that insists on honoring the past not as static or fixed, but as an evolving story we must continue to turn toward as a clarifying guide for the present.

This year’s Day of Remembrance passed amid many simultaneous crises that, while taking new forms — we ban different books; silence different, though familiar, histories; adopt new legal and legislative tactics — exist within the continuum of history, braided into the same tired stories of American exceptionalism and the ever-elusive American dream. But here, in these intertwined oppressions, there is hope to be found. As kato-kiriyama and Louis model, pulling at these threads — refusing to be silent or to bury our ancestors without their memories — disrupts the ongoingness of what we are meant to forget. As kato-kiryama told me, “Our memory work, as much as it’s tough and bitter and harsh … is also a gift. It is an arena of privilege and responsibility.”

traci kato-kiriyama is a Los Angeles–based multidisciplinary artist, educator, and community organizer who holds “community building and bridging” at the heart of her work. Navigating With(out) Instruments is a collage of poetry, micro-essay reflections, and “Notes” directed explicitly to herself, to other artists, to the world, to the Japanese American community. If Breaking the Silence offers a kaleidoscopic view of history through a multiplicity of voices and sound, Navigating With(out) Instruments is kaleidoscopic in form and content — moving from poetry to prose to epistle and back again, all the while sitting with the meanings of legacy, reckoning, repair, and transformation. The memory work that kato-kiriyama demonstrates through Navigating With(out) Instruments builds on and beyond Louis’s model. It remains rooted in the internal work of learning and hearing our own stories but acknowledges that the broader circumstances of our lives and geopolitical surroundings have shifted to demand different foci for our memory work.

kato-kiriyama begins the book by honoring the children she does not have, inviting readers to consider as valuable and meaningful even the pasts that have not come to be. Throughout the book, she repeatedly invokes burying — burying letters, bodies, clocks, heartbreak, memories — as if to offer a grounding in the close intertwining of life and death. Burying for kato-kiriyama is not silencing. Rather, burying as a motif operates as a particular manifestation of memory work — a way of naming, working through, and confronting the past that makes new growth, in open air, possible.

Navigating With(out) Instruments offers kato-kiriyama’s reflections on receiving her cancer diagnosis, stories about and for family members, ancestors, and her communities, and five of what she titles “Death Moments” — each a brief poetic meditation on the exigencies of life through brushes with death. Just as the repeated invocation of burying reminds readers that the work of remembering requires both a letting go and a return, these “Death Moments” give shape to the memory work that kato-kiriyama embarks upon in the book. For kato-kiriyama, memory work requires an engagement with the vulnerability of living — the fact that death will come, as it did for her grandfather, her father, as it nearly did for her — through the hard work of digging into and learning family stories, especially those that are hard to find or to hear.

kato-kiriyama’s memory work, like Breaking the Silence, is not static or finite, but a path outward. “When I’m asked about why I think our solidarity is important or why I work on reparations … I find myself talking about my grandfather and my grandmother,” kato-kiriyama said. Two poems, “No Redress” and “Last Time in D.C.,” give voice to her memories of her grandfather, who died in a car accident before redress, and her grandmother, one of the oldest Japanese Americans to receive a redress check in a ceremony in Washington, DC. Her grandmother’s joy at receiving the check, impossibly intended to compensate for past wrongs, combined with the bitterness of kato-kiriyama’s fruitless search for the justice her grandfather never had in his lifetime, serve to humble and motivate. “The memory work is exactly what drives me,” kato-kiryama told me, “because I feel it in my face, I get emotional, every time I think about my grandfather … it’s this little glimpse into generational pain, intergenerational pain and trauma.” This intergenerational pain for Japanese Americans is real and shapes our families to this day, but kato-kiriyama reckons with the fact that, for most of us, it provides just a glimpse — “an inkling into the fact,” kato-kiriyama says, “that I can’t even fathom what then it would mean to be a descendant of genocide or slavery.”

This perspective is crucial. The focus of memory work is not an external push to make other people care more about Japanese American history. Rather, the focus is on the internal work, using our community and family stories to drive us to study and to search, not to equate experiences, but to use our memory work to forge connections through the contexts of racism, white supremacy, and capitalism. It’s about placing our community stories alongside each other to orient us in a new way, toward each other.

When we can hold our family and community stories, with all their silences, and see them as essential components of capital-H History, we learn to hold multiple truths about the past at once. We cease to accept that the injustices of our present are inevitable parts of our future. We can begin to see a world we might build together.

Japanese Americans did many things with their redress checks: some opened college savings accounts for their children and grandchildren; some paid for retirement or care homes for aging parents or themselves; some donated the money, recognizing they were financially stable and wanting to support others; many donated to support the fledgling Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles; some rejected the payment entirely. In the early 2000s, at the age of 65, Nikki Nojima Louis took her redress check and went to graduate school at Florida State University for a PhD in creative writing.

While the payments marked the closing of one chapter, redress was an important inflection point for Japanese American memory work. Because of redress, we have national historic site designations, community education organizations, and federal granting programs to continue funding and supporting our healing. Today, our memory work must keep pushing us to see our histories and our futures as truly intertwined with other communities seeking justice and liberation. Standing with groups that continue to be explicitly targeted by racism and state violence — Muslim and Arab Americans and immigrants and refugees, in particular — are the most visible examples of solidarity emerging from this work. But Japanese American memory work also means reckoning with settler colonialism by having honest conversations about how we can encounter and preserve the sites where our families were incarcerated without further erasing Native stories and ties to the land. It means supporting Native Hawaiian sovereignty. It means speaking out in support of Japanese Latin Americans and Comfort Women still seeking redress and accountability. It means calling for Black reparations and, as part of that call, actively addressing anti-Blackness within our communities and reckoning with the ways that we have benefited from model minority mythology. In the face of renewed waves of anti-Asian violence, it means turning to our communities to keep each other safe and working together to undo the structures and policies that position Asian Americans as a wedge, pitting us against other communities of color to preserve white supremacy. Japanese American memory work today cannot be separated from broader visions of justice. As kato-kiriyama calls each of us, all the parts of us:

Let us remember we will never truly breathe whole breaths, as whole beings, as a whole country and people, until we reach a collective reckoning, and repair … until we become whole and so can exhale into a place of healing at the depths of the blood and marrow in our bones. Imagine that breath.

¤

LARB Contributor

Erin Aoyama is a doctoral candidate in American Studies at Brown University whose research is rooted in Asian American studies, relational ethnic studies, and public humanities. In addition to her doctoral work, Aoyama is co-director of the Japanese American Memoryscape Project and a curatorial assistant at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Learning in Being Lonely: On Jay Caspian Kang’s “The Loneliest Americans”

Summer Kim Lee reviews “The Loneliest Americans,” the new book by Jay Caspian Kang.

Trump’s Assault on Asylum: An Opportunity to Reflect on US Humanitarian Values

Sara Campos considers “The End of Asylum” by Andrew Schoenholtz, Jaya Ramji-Nogales, and Philip G. Schrag.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!