Maybe One Day I Will Learn How to Live: On John Freeman’s “Wind, Trees”

Scott Korb reviews John Freeman’s new poetry collection “Wind, Trees.”

By Scott KorbMarch 1, 2023

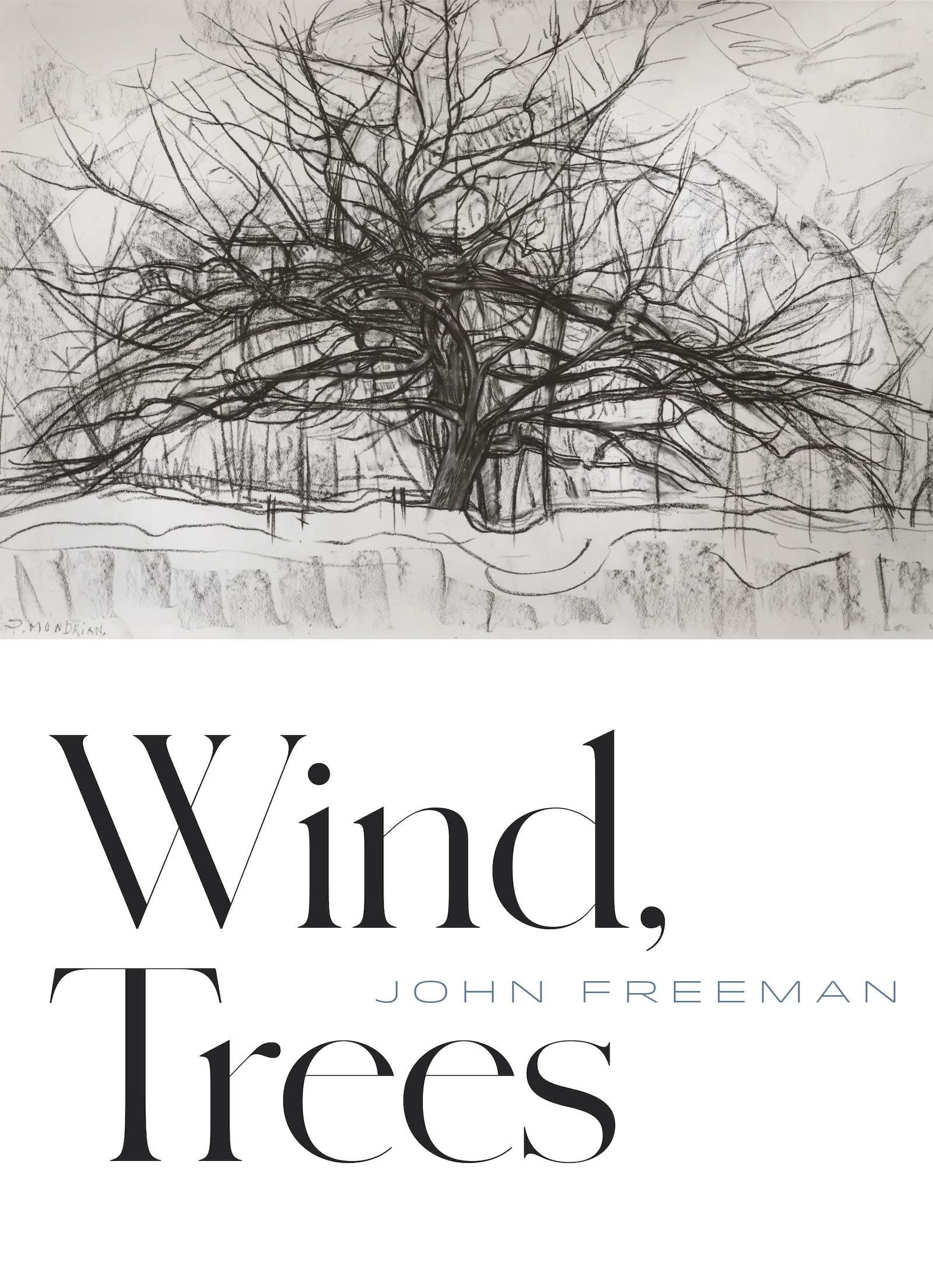

Wind, Trees by John Freeman. Copper Canyon Press. 96 pages.

ONCE THE RAINS came to Oregon last year, following a long dry summer and a fire season that again made it difficult to breathe, we opened the apartment windows and stowed our air purifiers. On our morning walks, the dog and I took our time to soak it in—the cool, the relief—under the rainforest canopies of the local park, strolling a path where fresh autumn runoff had already begun eroding stone walls left to bake and crack all summer, secured, I’d believed, by invasive English ivy. But maybe, instead, the ivy’s roots had loosened the stones in their hunt for water. I don’t know.

Every day is a lesson in the elements for a relative newcomer like me.

Over all of these days and months, I’ve been reading the new poetry collection by John Freeman, Wind, Trees (2022), likewise a lesson in the elements, including fire and ice, fear and trembling, with turns, too, on emigrant plants, difficult breathing, the love of a good dog, and a “four o’clock dark beginning like a rumor.” In winter, it gets dark early where I am too.

As a rule, I try not to read this way, toward identification. But it’s happened in this case; there’s no point denying that. After all, I see myself and my own comfortable life and my own comfortable habits in Wind, Trees: the possibility of calm domesticity during quarantine, dog walks through nature, daily toast with preserves. Reflected in these poems is the wherewithal and interest to look back on a life from middle age—to say, Freeman writes, of love lost, “the body inside my body turns over, / the one that remembers not being yours,” or to recall taking up boxing in “the waning days / of those years in London”—when some of what’s there to look back on is adulthood already behind us, when life has been long enough for us to have called other places home. (For me, this was New York City.)

Part of this ability and willingness comes with experience and time, the writer’s habits of attention and associative thinking. Freeman writes in “Loneliness” of Sunday afternoons spent in a London pub, the collapse of great and small changes time brings, what we all face together, what we each must face alone: “Every Sunday a matinee I attended for three years / as volcanoes exploded / and she died, / white slipped into my beard, / wars began and others ended.” Through the violent eruptions of nature and culture, private and public deaths, the pubgoers Freeman comes to know bear him up—and each other, we suppose—even as so much of his loneliness (and theirs) remains private. The poem, and the culture into which Freeman has stepped over these Sundays, presumes that some griefs—those griefs graying our beards—we share with others, and we can reach one another with a word or two of recognition or comfort: “Each Sunday the words gathering new weight / strangeness / as words do when you repeat them. / You alright.” Or, in “Receiving,” the lessons of seeing into the life of another being crosses species. Freeman reveals just how well, in time, he’s come to know his “sniffing, searching” dog: “Three things / will get her / to drop the ball: / a crap, a fox, / a ripe blackberry.”

Another aspect of Freeman’s attentiveness and reflection arises from the elemental fact that single days come and go, months pass and accumulate into years. “Among the Trees” begins, “Each morning on the common Martha stops” (Martha is the dog). The next poem in the collection, “Still,” opens this way: “Every day at lunch the gray heron / canters down from her branch in the brook.” We complete the day with “Show,” the next poem, which starts, “At sundown kestrels call to each other across the garden, flocking in the large elm tree.” The central place of animals across these poems, and their incremental disentanglement from his human life—from the dog he loves to the heron he recognizes to the soar of indistinguishable kestrels calling to one another—is another acknowledgment that life goes on, that there will be another season of bird calls after Martha and Freeman walk the common no more (Martha departing first, one presumes, another grief hanging over a book that’s dedicated to her). In other words, these three poems, like many others in the collection, seem to arise from a moment in life after one has learned a few key things and is looking ahead to what’s next, which inspires an urgency to learn a few things more before dusk.

The central place, in life, of openness and learning—from truths hard won to the great mysteries on the horizon—is what most animates this book, a realization I had while reading that provides some consolation after so easily identifying with the occasionally fraught yet so often so cozy lives depicted in these poems. Indeed, one of the early thoughts I had about Wind, Trees was that it seemed to have been mentored into existence. “Without” offers this possibility: “Maybe one day I will learn how to live / without, without her and her, and she and / them, without him.” The first line says it all, summing up the aesthetic and ethical consciousness of this collection, composed as a series of possibilities and missed opportunities (possibilities sometimes framed as missed opportunities) that seek fulfilment and a steady guide—mentorship—outside of the self, in others, and often beyond what’s human.

We’d expect, by the collection’s title and its two named sections, that we, with Freeman, might learn a thing or two from the wind—“Listen to what the air / is saying tonight // my friend”—and also from the trees: “What is a trunk / but a commitment? // Or bark but an awareness / that life eventually burns?” We might learn how to live without, too, from the lunchtime heron in “Still,” once part of a couple, who “now […] hooks alone, casting with her giant / beak. Stirring the water with a foot.” She fishes while Freeman watches, made to wonder at his own purpose while she lures small brook creatures into the shade she creates with her wings, balancing among the human trash we’ve dumped “amidst the glades”: “Cans of Coke, // T-shirts, a dishwasher, an old skirt. It’s become / the breakfast table for her. And us, what are we for? // To watch, mourn, to exclaim gladly?”

Wind, Trees clearly cares about the natural world and our place in it, our human relations to the elements and the animals, the damage we’ve done. A title like “The Heat Is Coming” hardly needs a poem at all. But Freeman makes no human claims on nature nor even really on nature’s behalf, refusing to speak with any certainty for anything as grandly mysterious and loving as a forest, which speaks its own languages, or that heron, whom Freeman can’t help but wonder whether to mourn or exclaim gladly about. (Offering each as a possibility, the poem, in the end, does both.)

And here, in the poet’s unwillingness to make unnecessary claims or draw conclusions inadequate to any moment, we see the influence of one of Freeman’s most important human mentors, the late writer Barry Lopez, who, of any experience of the natural world, would advise one to “step away from the familiar compulsion to understand.” Of this approach, Lopez credits his own human mentors, the Indigenous people he spent much of his life studying with and learning from. One example of this posture toward nature, from Lopez’s great final work Horizon (2019)—though captured originally in Granta, Freeman’s onetime editorial home—drew from an encounter among those Indigenous friends with a grizzly bear:

When they saw the bear they right away began searching for a pattern that was resolving itself before them as “a bear feeding on a carcass.” They began gathering various pieces together that might later self-assemble into an event larger than “a bear feeding.” These unintegrated pieces they took in as we traveled—the nature of the sonic landscape that permeated this particular physical landscape; the presence or absence of wind, and the direction from which it was coming or had shifted; a piece of speckled eggshell under a tree; leaves missing from the stems of a species of brush; a hole freshly dug in the ground—might individually convey very little. Allowed to slowly resolve into a pattern, however, they might become revelatory.

Lopez’s prints are all over this collection. “Centuries in the Woods,” for instance, captures patterns of human connection absorbed by the trees and played back in stillness: “When I lived in the woods I began to hear / conversations that had unfolded / across centuries.” And Freeman’s mentor is at least twice memorialized, transformed into the presence of wind itself in the poem “Dusk” and remembered, one assumes, in “Friendship,” as Freeman’s faraway friend, with whom he shares baseball: “Night games and their holy liturgy. Windups / and changeups, the living box score. Base / hits and pine tar, inside heat and extra innings. / Now I worry you’re keeping vigil over the smoking / tree line. Knowing when the roar of fire gets close / it’s time to go.”

The Barry I knew loved a box score—it didn’t matter the sport—and would trade them in the mail, he once acknowledged in the eulogy of a friend, “to see if the other fellow would pick up the hidden meanings in a set of numbers opaque to most—the bench player who played only six minutes and had no points, but had three steals and two blocked shots.” Barry also would have loved the chance in his friend John’s broken line to misread the long “i” in “windup” as a short “i” as in “wind up,” like in the first half of the book’s title. “Pine tar” and “inside heat” are also doubly meaningful, and when the roar of fire got close to his home in that terrible late summer of 2020, Barry was forced to leave, though not alone.

The writer Debra Gwartney, my Oregon friend who first pointed out to me the invasion of English ivy, who, along with her husband Barry, had once promised us summer suns and warned of autumn smoke, captured that moment of flight in the gorgeous, elegiac 2021 essay “Fire and Ice.” (Like her husband’s writing about the bear, this was also published in Granta.) She was awakened first by a friend’s phone call, then a man at the house:

I pulled on long pants, though the temperature was sweltering and the house already choked with smoke and grit. Barry was sleeping in our guest cottage that night, a few hundred feet away. I was headed there to wake him when the young man appeared on our porch hollering words my friend had already said: Get out now.

Freeman, too, appears in Gwartney’s essay, as Barry’s “young friend John.” In the final days of her husband’s life, now exiled in Eugene, Oregon, while their home sat uninhabitable amid the char of the Holiday Farm Fire, Gwartney wrote of John and Barry talking over the phone about a final essay the dying man was working on, their conversation springing “open a clarity of mind Barry was known for, the next revision cooking on high in him now.”

“Fire and Ice” tells volumes about those final, painful days of Barry’s life, with that “last essay still rolled in the typewriter at home.” (It would remain undone.) It’s as deserving of your time as any great story you’ve read about love and loss—and as a remembrance of Barry Lopez, no other could capture him with more clarity, intimacy, and care, in large part because Gwartney seems driven by a compulsion to understand: “How was I to make peace with my husband’s disappearance before he had actually disappeared? How was I to give up on a last chance to express what we meant to each other?” Near the end, she writes: “‘Barry, do you know who I am?’ I said.” (To date, she has published three searching essays about the loss of her husband; the loss of their land to the fires; the climate disaster; and the human folly, desirousness, and greed at the center of it all. She also seems to know, without having to say so, that the human compulsion to understand will always be unfulfilled, a strong current in all of her work.)

For his part, too, the lesson Freeman takes and the assurances he offers his mentor in his own remembrance, “Dusk”—“how badly I want you to know we have / the torches now, my friend, we’ll protect the flame”—seem, at first, to arise from the very compulsion to understand that Barry warned against. But then you read again and see that the line expresses (“how badly I want”) the same uncertainty and longing that is contained in every human desire, that follows every loss.

Another poet friend has a rule for students who write about nature: no personifying. The moon cannot have a face. Willows cannot weep. (This same poet would no doubt complain about the sort of reading that has me so easily identifying with the poet and his subjects.) One point of this rule may be to eschew clichés, a lesson for writers in avoiding dead language. Another, I like to think, is to keep us from seeing in the natural world only those qualities we see in human life, projecting humanity so completely onto a nonhuman world that we paper over all mystery and all we have to learn, to express the existence of other life in terms of an existence we already possess and, inasmuch as we do, understand. Wind, Trees was composed in this nonpersonifying spirit, open to dogs and herons and bears in their own terms.

The trees and the wind, too, are present in the world of these poems to be neither possessed nor harnessed for human purposes—they exist beyond the purpose of mentorship. Still, much remains to be learned in these poems of middle age, of and from nature, of and from our human mentors—those Barry would call our elders—of and from a book bound by the irreconciled tension between one thought (“Maybe one day I will learn how to live”) and another (“how badly I want”). These poems don’t yet know, the way the wind and trees do, that learning to live may mean not wanting at all.

¤

LARB Contributor

Scott Korb, director of the MFA in Writing program at Pacific University, is the author and editor of several books, including Light without Fire: The Making of America’s First Muslim College, and the collection Gesturing Toward Reality: David Foster Wallace and Philosophy. He lives in Portland, Oregon.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“Muscle Memory” by Jenny Liou

A Precarious Peace: On David Mason’s “Pacific Light”

Siham Karami reviews David Mason’s new collection of poems, “Pacific Light.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!