“Marlowe Would Be Proud”: On “The Annotated Big Sleep”

Geoff Nicholson wanders the mean streets with Raymond Chandler’s “The Annotated Big Sleep” for a Baedeker.

By Geoff NicholsonOctober 11, 2018

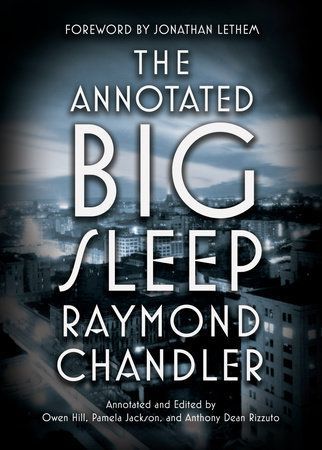

The Annotated Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler. Vintage Crime/Black Lizard. 512 pages.

I CAME LATE TO Raymond Chandler, and I don’t know if it was in the best or worst possible way. I had my degree in literature, and I had read not a single word by Chandler. It was a rainy afternoon in London and I needed to kill a couple of hours, so I went to see a showing of The Big Sleep. The film I saw, however, wasn’t the 1946 Bogart-Bacall classic (which I’d only heard about), it was the 1978 remake directed by Michael Winner and set improbably, unconvincingly, in England. The film is universally despised. Roger Ebert said it “feels kind of embalmed,” although plot-wise it’s strangely faithful to the novel, and the cast is fantastic — Jimmy Stewart, Candy Clark, Richard Boone, Oliver Reed, with Robert Mitchum as Philip Marlowe. Mitchum has always seemed to me the perfect Marlowe, and far more believably tough and insolent than Humphrey Bogart; I just wish he’d played the part 20 years earlier. He first played Marlowe in 1975 in Farewell, My Lovely, when he was in his late 50s; he was 60 by the time he made The Big Sleep, and he doesn’t look a youthful 60.

You could argue that if Chandler’s genius could shine through that dreadful adaptation, then it’s pretty much unassailable. And shine through it did. I was hooked, and went back to the source. I immediately read The Big Sleep (1939), his first novel, and then the rest of the oeuvre, and I’ve been increasingly hooked ever since. I consider myself an enthusiast rather than an expert or a scholar, although there’s a shelf in my office heavy with Chandler-related volumes: the letters, the biographies, the notebooks, and various Los Angeles–related items that include Raymond Chandler’s Los Angeles (1987), Chandlertown: The Los Angeles of Philip Marlowe (1983), and Tailing Philip Marlowe: Three Tours of Los Angeles — Based on the Work of Raymond Chandler (2003). The Annotated Big Sleep, with a short but excellent foreword by Jonathan Lethem, will eventually join them.

But here’s the question: when I read The Big Sleep for the first time (or subsequently, for that matter), was there much in there that I didn’t understand? And I’m not talking about plot matters such as who killed the chauffeur, or why the cute but borderline-insane murderess isn’t prosecuted, but rather matters of fact and vocabulary.

Did I feel the need to reach for the dictionary and look up “swell” when Marlowe says to Vivian Sternwood, “I don’t mind your showing me your legs. They’re very swell legs”? Did I wonder what a jerkin was, or a chiseller, or a bookplate? Was I puzzled by the terms “hot toddy” and “got the wind up”? Did the words parquetry, stucco, or croupier seem unfamiliar? After I’d read that General Sternwood was propped up in “a huge canopied bed like the one Henry the Eighth died in,” did I feel the urge to check the date of Henry VIII’s death?

Honestly, I did not — but Owen Hill, Pamela Jackson, and Anthony Dean Rizzuto, the three editors of The Annotated Big Sleep, certainly think that all those things I’ve listed are worthy of explanation, which, I think, raises the question of who reads The Big Sleep and who those annotators think reads The Big Sleep.

Pico Iyer, in his essay “The Mystery of Influence” (2002), says of Marlowe, “Of all the great figures of the twentieth century, he seems one of the most durable, in part because he travels so well and so widely.” And he tells us that Haruki Murakami began his career by translating Chandler into kanji and katakana scripts. It’s not hard to imagine that Japanese readers might find something of the noble, tarnished samurai in Marlowe, though what they make of a line like, “She has to blow and she’s shatting on her uppers. She figures the peeper can get her some dough,” is anybody’s guess. Somehow they cope.

¤

The fact is, it’s rare, if ever, that we read a book and understand every single word, every literary allusion, every local or historical reference, just as we don’t understand every single thing we encounter as we go about our lives. And, of course, with fiction it gets harder depending on the age of the work and our cultural distance from its milieu. In a piece on John Updike’s Rabbit Is Rich (1981), Martin Amis writes, “Like its predecessors, the novel is crammed with allusive topicalities; in a few years’ time it will probably read like a Ben Jonson comedy.” I imagine there may be readers of that essay who could use a little annotation explaining the nature of Ben Jonson’s comedies.

If the common reader happily misses a few references, we tend to take it for granted that the best literary works will require explanations, glosses, and readers’ guides. Many have read James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) with a map of Dublin, Ireland, and a copy of Ulysses Annotated: Notes for James Joyce’s Ulysses (1988, by Don Gifford with Robert J. Seidman) close at hand. Joyce would have been delighted.

Steven C. Weisenburger’s A Gravity’s Rainbow Companion: Sources and Contexts for Pynchon’s Novel (1988) is a great help in understanding much abstruse material in Thomas Pynchon’s 1973 masterwork; although, when I laid hands on the compendium (a good decade after I’d first read the novel), I was thrilled to find that he’d got various things wrong, including not knowing the English meaning of “minge.” And this is one of the joys of annotated volumes: seeing what the editors did and didn’t explain.

And it doesn’t stop at high literature. There’s a subgenre of annotation that seeks not to explain evident difficulties, but to show the complications in apparently uncomplicated texts. Martin Gardner is the boss here. Having annotated Lewis Carroll’s Alice volumes (and declared Carroll to be sexually “innocent”), he went on to annotate books by G. K. Chesterton, Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798), and Ernest Thayer’s “Casey at the Bat: A Ballad of the Republic — Sung in the Year 1888” (1888). His publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, runs a list of annotated volumes that includes The Annotated Little Women (2015), The Annotated Peter Pan (2011), and The Annotated Wizard of Oz (2000). Do these works need annotation? The question is moot, since there’s clearly a market and an audience; and if we’ve learned anything in the last several decades, it’s that scholarship can be applied to popular, or even low, culture, just as successfully as it can be applied to high art.

¤

Raymond Chandler would have understood the dichotomy and might have reveled in the contradictions as they applied to his own work. In writing for a pulp audience, he knew he was slumming, inhabiting the less respected and less examined districts of the city of words. But he was not modest about his talents or his ambitions. He’d had an English classical education at London’s Dulwich College, which contained Marlowe House. He knew that his hero’s name might evoke Christopher Marlowe for some readers, but certainly not for all. The earliest version of Chandler’s detective is named Mallory, as in Thomas Malory, the author of Le Morte d’Arthur (1485), but maybe he came to think that was going too far.

In a 1949 letter to Hardwick Moseley, Chandler wrote, “The aim is not essentially different from the aim of Greek tragedy, but we are dealing with a public that is only semi-literate and we have to make an art of a language they can understand.” His invocation of Grecian heights strikes me as going way too far.

¤

No doubt the “semi-literate” public will not be rushing to read The Annotated Big Sleep, but for the rest of us, there’s a huge amount to enjoy in the book. I found myself more intrigued by the background information than by the editors’ close reading of the text, which sometimes feels like they’re breathing over your shoulder and making arch remarks, telling you how to read (for example, “Carmen is back to her default between the kitten and the tiger — for now”), but no doubt some readers will feel the opposite way.

Some of this background comes into the “who’d have thought it?” category. For instance, we’re told that in the 1930s, Los Angeles had 300 casinos and over 40 newspapers; hard to say which of those numbers is more surprising. Information about the city’s population and ethnic makeup is fascinating. I don’t think many of us regard 1930s Hollywood as the center of Jewish life in Los Angeles. The book quotes the journalist Garet Garrett (not his birth name), who visited the city in 1930 and wrote,

you have to begin with the singular fact that in a population of a million and a quarter, every other person you see has been there less than five years. More than nine out of every ten you see have been there less than fifteen years.

In 1939, the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration authored a book titled California: A Guide to the Golden State. In it, they called Los Angeles the “fifth largest Mexican city in the world” (a distinction that nowadays belongs to Chicago). We also learn that between 1920 and 1930, 30,000 Filipinos migrated to California. They were known as dandies and sharp dressers, which explains Marlowe’s line to Carmen Sternwood that she’s “[c]ute as a Filipino on Saturday night.” I guess this is a racial slur, but as these things go it seems quite gentle.

There are some revelations relating to Marlowe himself — details that are easy to miss or simply skim over. For instance, Marlowe’s description of himself on the novel’s first page, “I was neat, clean, shaved and sober, and I didn’t care who knew it,” is army slang — “neat, clean, shaved and sober” means ready for inspection. Later, in a description of Marlowe’s apartment, we read he has “an advertising calendar showing the Quints rolling around on a sky-blue floor, in pink dresses.” I had never thought to wonder who the “Quints” were, but we’re told these are the Dionne quintuplets, identical French-Canadian girls born in 1934, the first quintuplets to survive past infancy. A couple of them are still alive, if Wikipedia is to be believed.

There’s also an interesting consideration of Marlowe’s daily rate — $25 plus expenses, which some clients find a bit pricey. It’s the equivalent of $400 in today’s money, which sounds a tidy sum, although considering what Marlowe has to go through to earn his money, it’s not altogether unreasonable.

The annotations make much of the geographical and topographical background to the novel, describing Laurel Canyon, the Pacific Coast Highway, Franklin Avenue, and noting landmarks such as the Sunset Towers and Bullocks on Wilshire. But as becomes obvious to anyone who’s tried to walk in Marlowe’s footsteps (something I did when I first started living in Los Angeles), one of Chandler’s skills was to blend a detailed real city with one of his own invention. So yes, being told that Geiger’s bookshop is on Hollywood Boulevard by the corner of Las Palmas seems utterly precise, but Stanley Rose, who had a bookstore at more or less that location, isn’t much of a model for Geiger: you’d find Rose hanging out in his store talking with Hollywood literati rather than taking nude photographs of drugged heiresses. At other times, Chandler simply made up the names of streets; Laverne Terrace and Alta Brea, for example, sound completely authentic, but you won’t find them on any map.

The editors, inevitably, and reasonably enough, wade into the inscrutable and contested sexuality of Chandler and Marlowe. I’ve never been sure whether Marlowe’s homophobia (as Chandler wouldn’t have called it) was his own, or Chandler’s, or simply something that pulp readers would have expected from a tough guy detective. It’s well known that quite a few people who met Chandler assumed he was gay, but that raises more questions than it answers, and there’s certainly no evidence that he ever had any sexual relationships with men. Still, the annotations are interesting in themselves. They tell us that the “1920s and early ’30s saw no fewer than ten new terms for ‘homosexual’ recorded,” including “queer.” We also learn that, as a result of prohibition, gay and lesbian subcultures had become more accepted in select quarters, while still remaining hidden. Once you were breaking the law by drinking illegally in clubs and speakeasies, you were less likely to cut up rough about seeing some same sex couple and a drag act or two.

The editors also raise the possibility that when Vivian Sternwood, wearing a “mannish shirt and tie,” says to Marlowe, “I was beginning to think perhaps you worked in bed, like Marcel Proust,” she may be accusing him of being gay. I don’t quite buy that, but then, I don’t have to.

I do buy, eagerly, the book’s analysis of the instances where Chandler “cannibalized” his own early stories and incorporated them in the novel. They show, despite Clive James’s insistence to the contrary, that Chandler’s writing improved very rapidly indeed in the six years between the publication of his first short story, “Blackmailers Don’t Shoot” (1933), and The Big Sleep (1939).

The book is illustrated with dozens of images, book and magazine covers, movie stills, maps, period photographs. These are well chosen and very useful. I wish some of them were bigger, especially the maps, and I wish some of those pulp covers were in color, but you can’t have everything.

For what it’s worth, I only found one error, maybe half an error. The book has Le Corbusier as sole designer of the chaise longue basculante: these days Charlotte Perriand is usually given her due as co-designer.

The book’s bibliography is lengthy without being exhibitionistic, and the editors have even managed to track down a treatise on “the lost art of walking,” by one Geoff Nicholson, that contains a short section about Chandler. Top-notch sleuthing. Marlowe would be proud.

¤

LARB Contributor

Geoff Nicholson is a contributing editor to the Los Angeles Review of Books. His books include the novels Bleeding London and The Hollywood Dodo. His latest, The Miranda, is published in October.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Ramble About Books About Walking

Geoff Nicholson strolls through several books on walking.

An A to Z of Iain Sinclair on the Occasion of the American Publication of “The Last London: True Fictions from an Unreal City”

Geoff Nicholson goes through the alphabet to describe the multifaceted work of Iain Sinclair.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!