Marikana, Part II: Looking For Answers to a South African Massacre

By Alex LichtensteinJanuary 4, 2013

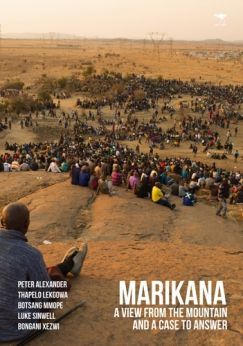

Marikana by Bongani Xezwi, Botsang Mmope, Luke Sinwell, Peter Alexander, and Thapelo Lekgowa. Jacana Media. 228 pages.

In a September 1, 2012 article for the Los Angeles Review of Books, historian Alex Lichtenstein examined the background of the massacre of striking miners at Marikana, looking closely at the dismal record of South Africa’s platinum industry. Here, in a review of the first full-length study of the events of August 2012, he brings the story up to date.

¤

LESS THAN FIVE MONTHS after South African police shot down 34 striking miners at Marikana, North West Province, on August 16, 2012, life goes on in South Africa, although perhaps it would be an overstatement to say that things have returned to normal. As Peter Alexander and his colleagues note in their stunning and timely postmortem investigation of the massacre, in South Africa “one has to go back to the Soweto Uprising of 1976 to find an example of government security forces murdering more protestors than at Marikana.”

Then, of course, security police murdered schoolchildren who lived in a racial dictatorship. Today, workers are being shot down by a government they elected to power. Nevertheless, at the recent African National Congress (ANC) elective party conference at Manguang, President Jacob Zuma received reaffirmation and will stand for a second term as the party’s presidential candidate in the 2014 elections. Selected as Deputy President of the ANC was Cyril Ramaphosa, who as a Board member of Lonmin mining corporation (and owner of nine percent of that company’s shares) was deeply involved in the labor management conflict at the platinum mines that touched off the strike and the August bloodletting. Indeed, Ramaphosa has been accused of urging police to suppress the unauthorized strike in the first place. Gwede Mantashe, former leader of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) remains as ANC general secretary. Current NUM President, Senzeni Zokwana was elected to the ANC’s National Executive Committee. The three main forces that Alexander charges with culpability in the massacre — party, company, and union — now constitute half of the ANC’s political leadership, and thus South Africa’s. Many South Africans anxiously await the official Farlam Commission of Inquiry report on the massacre, though given the growing distrust of the government, few really imagine it will get to the bottom of things.

Under apartheid, the white supremacist government loved to establish commissions to investigate every social “tragedy” bedeviling the country, whether it be the economic unsustainability of African reserves (1954), the Sharpeville Massacre (1960), the Soweto uprising (1976), the need for black trade unions (1977–79), or, back in the 1940s, gold miners’ strikes. Today, the testimony contained in these reports serves as a fabulous resource for historians. At the time, however, each one, released to great fanfare, engaged in handwringing and then promoted mild reform as a means of staving off larger transformations. As Peter Alexander, Thapelo Lekgowa, Botsang Mmope, Luke Sinwell, and Bongani Xezwi suggest in their courageous independent investigation of Marikana, A View from the Mountain and a Case to Answer, post-apartheid commissions may be equally limited in their vision. The Farlam Commission, they charge, “has not observed working conditions underground and operates in a courtroom environment alienating for ordinary people.” Nor did press coverage at the time offer much testimony from the workers’ side of the barricades.

A View from the Mountain, as its title suggest, aims to see past these blind spots by examining the events at Marikana from another perspective, that of the striking and peaceful workers huddled on the “koppie” before they were mowed down mercilessly by police. It is an extraordinary document in a number of respects. Alexander, a professor of sociology at the University of Johannesburg (UJ), and his four collaborators have produced an invaluable document that represents a “first draft of history,” a term of art usually reserved for investigative journalism, but one that in this case does not fully do justice to this publication. Part investigative report, part oral history, part polemical pamphlet, A View From the Mountain illustrates what can be achieved when academics work closely with activists. Alexander holds a Research Chair in Social Change at UJ, a once Afrikaner-dominated institution that has been reinvented as a think tank for scholars seeking to transform post-apartheid South Africa. The other authors, however, come to this project through affiliations with social movements like the Landless People’s Movement and the Soweto Electricity Crisis Committee. Lekgowa worked for a platinum mine; Mmope is a herbal healer. Several clearly speak isiXhosa, the first language of most of the migrant miners they interviewed for the book.

Based on firsthand testimony of dozens of eyewitnesses and participants, A View from the Mountain offers the most detailed reconstruction to date of the events leading up to and including the massacre of August 16. It contains a number of striking findings that the Farlam Commission will be hard-pressed to ignore in its own deliberations. Their report is greatly enhanced by vivid maps that allow readers to trace the geography of the workers’ protests and the massacre, as well as photographs of the terrain, platinum miners, and their families. But Alexander and his research team also advance a stinging indictment, one that calls attention to an act of great injustice and that lays out for the ANC, for Lonmin, and for the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) as they say, “a case to answer.” In bluntest terms, the 200-page book charges that the massacre at Marikana “was not only preventable, it had been planned in advance” and that the miners “were brutally murdered” to maintain the economic status quo in the New South Africa, or in their words, “in the interests of capitalist relations of production.”

Regardless of the truth of these specific accusations — the first subject to eventual proof or refutation, the second more subjective and interpretive — the book serves as an important historical source in its own right, allowing platinum workers from Lonmin’s very profitable mines to speak in their own voices, albeit under the necessary protective cloak of anonymity. The basic narrative of the strike and the massacre, which takes up about a quarter of the book, is followed by 13 interviews and three speeches, representing the views of strike leaders, rank and file workers, and their families. As sociologists and ethnographers, Alexander, Lekgowa, Mmope, Sinwell, and Xezwi took the time to win their informants’ trust (interviewing them in their own language, for example) and even traveled to the Eastern Cape to interview the families of the many migrant workers who journeyed to Marikana to earn a living as rock drill operators (RDOs) and to die on the mines, as generations of migrant mineworkers in South Africa have done before them. Of the 45 workers who died in the strike and the ensuing massacre, 26 were buried back in the Eastern Cape, over 500 miles from Marikana’s mines and killing fields. Interviews with the miners themselves include life histories, revealing the deep structural continuity in the migrant system that shapes black workers’ experiences in South Africa to this day. And, as the authors point out, they carried out most of these interviews before workers gave any official statements that tend to harden narratives into less spontaneous form. Thus, as a document of oral history recorded immediately after the fact, A View from the Mountain bears witness to the struggle of ordinary South African workers, a struggle that union leaders, ANC party functionaries, Farlam commissioners, and former trade unionists now sitting on corporate boards all seem to have forgotten about.

For starters, A View from the Mountain reveals the social conditions under which South African platinum miners, especially the skilled RDOs, make their living. Hours are long, the miners’ health and safety remain precarious, and the pay of R4000–R5000 (about $500) a month barely suffices to permit miners to live in the surrounding shantytowns and to pay their own expenses let alone those of the many family members (as noted, often living elsewhere) dependent on their wages. In Lonmin’s Karee mine, the strike’s epicenter, RDOs complained that they had no assistants underground, thereby effectively doing the work of two men for a single man’s pay — a classic “stretch-out,” a common spark for labor conflict. As Alexander and his team show, such grievances against employers were compounded by the RDOs’ growing dispute with the leadership of their union, the NUM, led in the “struggle” years of the 1980s by none other than Cyril Ramaphosa, before he entered business. Conflict between rank and file workers, who felt the union disregarded their complaints, and NUM leadership had been brewing since May 2011, when the NUM dismissed a popular local leader. Things came to a head in early August 2012, when miners from several platinum mines in the Marikana district decided to present a demand for increased wages directly to Lonmin management, bypassing the union they felt no longer spoke for them. When Lonmin refused their entreaties and referred them back to the NUM, the stage was set for tragedy.

There are no parties fighting, here only workers, workers are fighting for their rights and they want their money and they are being killed by NUM and [NUM President] Zokwana and the mine and the government that we vote for every day.

— Mineworker

Perhaps the most shocking thing that emerges from these interviews is not just the police killings of August 16, but the violence wielded against strikers by the union leadership preceding the massacre. Confronted by union members who had reluctantly agreed to follow protocol and take their grievances to the NUM, the union’s leadership opened fire on its own members, killing at least one worker. Mincing no words, Alexander describes this turn of events as “one of the most despicable acts in the history of the labor movement.” Following this, workers gathered traditional weapons to defend themselves against further attack from NUM leaders and set up an encampment on nearby Wonderkop Koppie, “the mountain,” where less than a week later they met their fate as attempted negotiations with Lonmin and the NUM — barely reciprocated in any case — broke down. In the interim, a brief and unprovoked clash with police took the lives of 10 striking miners.

Corroborated by multiple worker testimonies and recounted in gripping detail in A View from the Mountain, the final massacre on August 16 unfolded in three phases, each successively more brutal and less explicable by the official narrative of police “self-defense” that very quickly came to frame media accounts of that day’s events. In the first phase, a group of several thousand miners tried to flee the refuge of Wonderkop Koppie towards their shantytown residences as armed police and soldiers encircled strikers with razor wire, armored vehicles, and helicopters, and then opened fire without any warning, using live ammunition rather than the riot dispersal weaponry at their disposal. Up to eight deaths ensued from this initial fusillade, most of them inflicted from behind. In the second phase, a smaller group of panicked workers sought an alternate escape route through a gap in the razor wire blockade established by police. This is the source of media images of armed workers apparently rushing police lines. But as one survivor remarked, “People were not killed because they were fighting […] We were shot while running. We went through the hole [in the fence], and that is why we were shot.” In this encounter, 12 more miners met their deaths. In the third and final phase, police literally hunted down escaped workers at a distance from the initial encounter on what Alexander calls the “Killing Koppie.” There, without any provocation, they simply murdered at least 13 more unarmed and terrified men, Alexander charges. “Whatever view one takes of the initial killings, it is clear that the men who died on the Killing Koppie were fleeing from the battlefield,” he observes. "This was not public order policing,” Alexander concludes. “This was warfare.”

Certainly some of these facts can be gleaned from scattered existing news reports, particularly those that appeared in an independent paper called the Daily Maverick and the left journal, Amandla! But until now, no one has constructed as clear and coherent account, step-by-step, of what happened that day on the mountain. That said, it remains difficult to know if what Alexander and his fellow researchers have gleaned from the compelling testimony of the Lonmin workers will remain the definitive story of events. Their singular achievement is to secure the perspective of the striking miners, a perspective ignored or invisible to many journalists who appeared on the scene in the massacre’s immediate aftermath and then moved on to other stories. But like any partial account, this one too may contain distortions, half-truths, and misapprehensions, especially given the chaos, trauma, and terror that attended the events in question. Since many of the most damning details match up in several interviews, though, they cannot be dismissed as one person’s idiosyncratic experience.

South Africa is a democratic country but we as mineworkers are excluded from this democracy.

— Mineworker

Many questions about the massacre remain unanswered. We still have no grasp of the motivations of the police. Were they acting at the behest of the mining corporation, as some workers suggested? Of the NUM, as charged by others? Of certain elements in the ANC leadership, and if so, at the local or national level? Alexander contends the massacre should be understood as a premeditated act of state repression, but the evidence for this explosive accusation remains (for now) limited, if suggestive. In any case, what can explain the extraordinary brutality of the police, which far exceeded anything required to break the strike and terrify platinum miners into quiescence? Unaddressed in these interviews, or in the narrative of the massacre presented in this pamphlet, is the anger and resentment underpaid police may have felt towards the miners, perhaps for ethnic or political reasons, or perhaps to avenge two of their own fallen comrades, allegedly murdered by strikers the week before. While there may be good reason to question the limited vision of the Farlam Commission, its report may yet contain some important further documentation, as Alexander and his team readily acknowledge.

As a polemical pamphlet, rather than an investigation, however, A View from the Mountain does far more than charge “agents of the state and capital” with deliberately killing workers who chose to withhold their labor from commodity production. Animated by a non- (or anti-) Communist left socialist undercurrent that persists from the days of “the Struggle,” A View from the Mountain speaks directly to a longstanding debate in South Africa about the nature and exercise of working-class power. For Alexander et al., the Marikana strike represents a potential vindication of a syndicalist “bottom-up” approach to workplace struggle; those on this side of the debate have always been reluctant to defer to the leadership of the ANC and its South African Communist Party (SACP) allies, instead championing “raw working class power unhindered by the tenets of existing collective bargaining and middle class politics.” Despite the deaths of their comrades, striking Lonmin workers refused to capitulate, eventually bringing the company to the bargaining table where they secured a wage increase of 22 percent, a significant gain if less than their original demand. Much to the consternation of both corporate and union leaders in South Africa, not to mention the ANC and the SACP, this success subsequently led, Alexander and company suggest, to a series of “unprotected strikes, led by rank-and-file committees, which spread from platinum mining, into gold, and on to other minerals,” and even now have yet to fully abate. While the country’s most powerful trade union federation, COSATU (NUM is its largest affiliate), remains firmly embedded in the governing “tripartite alliance” with the ANC and SACP, there is obviously much disquiet in its ranks, which these researchers applaud and greet as a victory for the Marikana strikers.

We must point out that the unions that we have trusted for so long, the unions that have been at the forefront of every aspect of the employees, I do not know what is happening to them. They are definitely failing the employees [… ] They are also owners of these mines. They sit on the board with the owners of these mines. They [NUM] have lost focus and direction to lead and champion the causes of the employees.

— AMCU general secretary Jeff Mphalele

From this angle, as a bureaucratic organization the NUM (and perhaps other COSATU unions) no longer represents the aspirations or interests of its rank-and-file members, having been co-opted by state, party (the ANC), and even mining capital. Workers quickly spot the gulf between their daily lives and those of union leaders, who seem remote and uninterested in redressing their shop-floor grievances or reporting back to them about negotiations with the company. The perks and generous pay packets taken home by NUM leadership, supplied by Lonmin and other mining houses, may lead these former militants to serve the mining industry’s interests, not those of their membership. The corporatist bargain between a privileged union leadership, powerful mining concerns, and a governing party eager to reward its leading members with the perquisites of power, prompted the initial NUM attack on striking miners that proved the opening act of the massacre. As Alexander observes, “When Marikana workers demanded to talk directly to their boss they were attacking the pivotal component of a labor regime that had worked to the advantage of union leaders and the companies alike.” This dynamic, far more than any alleged “rivalry” between the established NUM and such upstarts as the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU) (as widely reported in the press), is the central problem of labor relations in South Africa today. Thanks to growing dissatisfaction with the NUM, AMCU has indeed made some inroads into the mine union’s membership base. But as Alexander points out the Marikana strike in fact “united the workforce and cut across unions.” Marikana, he insists, “represented a rank and file rebellion, not an inter-union dispute.”

We have been struggling while the union leaders were comfortable, drinking tea. When they have a problem, the management helps them quickly.

— Mineworker

Such workers’ activism has been dismissed — by police, union, and company — as nothing more than the expression of prepolitical, pre-modern, or “traditional” sensibilities of rural workers unable to follow the established rules of labor negotiations, and suggestions have been made that armed workers’ foolhardy courage derived from their irrational faith in the ministrations of sangomas (“witch doctors”). “In reality,” Alexander points out, “the workers operated through an elected and representative workers’ committee, one typical of well-organized modern strikes,” if no longer beholden to the NUM, which many workers regarded as corrupt and in the pay of the mine owners. A wildcat strike does not depend on muti (“witchcraft”) for its motivation.

A View from the Mountain makes the further case that South Africa’s growing epidemic of unauthorized rank and file strikes is a symptom of a larger malaise. Low wages, high unemployment, and outrageous levels of social and economic inequality continue to go unaddressed by the ANC government, even while a thin layer of black businessmen, ANC beneficiaries, and union leaders ascends to the upper ranks of the wealthy, once reserved for South African whites. Whether, as these authors hope, the widespread disaffection this engenders among ordinary South Africans portends a challenge “from the left” to the ANC and its SACP allies remains uncertain. Nevertheless, wildcat strikes, while nominally directed at big mining capital, can also pose a threat to party, union, and even state, and thus force the ruling coalition to choose sides between workers and their employers. Whatever light the Farlam Commission eventually shines on the murky details of the massacre itself, it seems clear as day which side the ANC, the SACP, and the NUM have chosen.

¤

LARB Contributor

Alex Lichtenstein is the author of Twice the Work of Free Labor: The Political Economy of Convict Labor in the New South (Verso, 1996). He teaches U.S. and South African history at Indiana University, in Bloomington, and is a book review editor for the internet discussion group H-SAfrica.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!