Madness as Method: On Andrew Hussey’s “Speaking East: The Strange and Enchanted Life of Isidore Isou”

A new biography of the founder of Lettrism, the “avant-garde of the avant-garde.”

By Marius HenteaJanuary 7, 2022

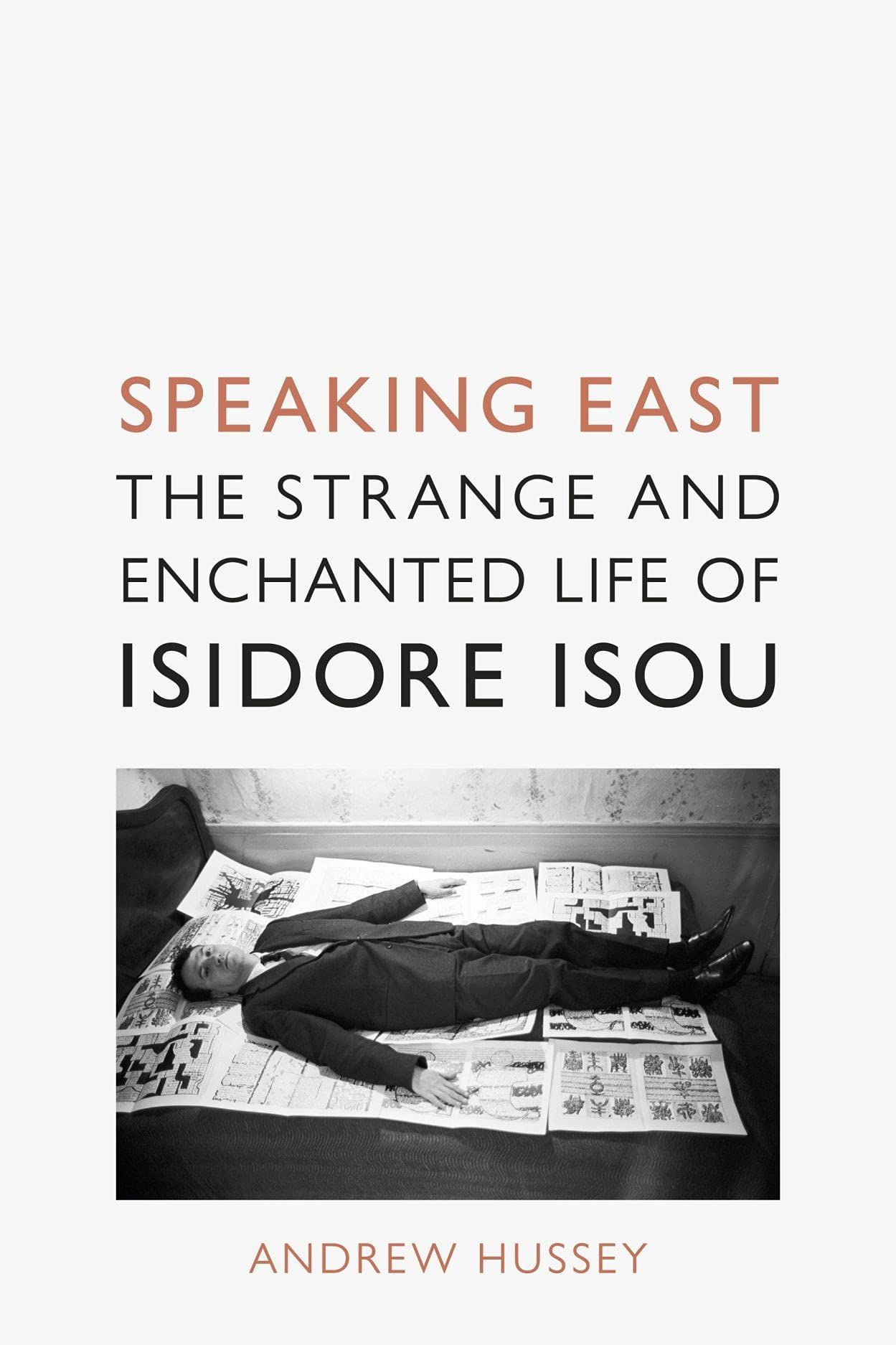

Speaking East: The Strange and Enchanted Life of Isidore Isou by Andrew Hussey. Reaktion Books. 324 pages.

IN LATE JANUARY 1941, Bucharest, Romania, was overrun by a barbaric pogrom that resulted in over 120 deaths, the looting of thousands of Jewish shops and homes, and the desecration of numerous synagogues. Sixteen-year-old Isidor Goldştein, an administrative secretary, found himself rounded up alongside 200 other Jews at an Iron Guard headquarters near the city’s Jewish district. For several days, they were beaten savagely with clubs, planks, and crowbars; if they asked for water, a basin filled with blood was kicked their way. Between beatings, the depleted and weary Jews were forced to do exercises for the amusement of their torturers. Insults like “dirty Yid” and folk songs about how the popor (people) was seizing control of its national destiny by exterminating the Jews filled the air. When even the Legionnaires tired of all the beating, two groups were formed: one, in line for further abuse, was eventually released, while the other, numbering nearly 90 souls, was taken to a forest where bullets ended their ordeal.

By mere chance, the young Goldştein was placed in the group that survived, but the memories of that night, as Andrew Hussey argues in his riveting biography Speaking East: The Strange and Enchanted Life of Isidore Isou, were the impetus — the “emotional core” — behind the strange, expansive, and ultimately overwhelming body of work that would appear under the name “Isidore Isou.” Having confronted certain death and witnessed indescribable savagery, Isou vowed not to die anonymously as so many of his brethren had. His trademark megalomania as the inventor of Lettrism — “It is a name and not a master that I wish to be […] the Name of Names: Isidore Isou. […] The Messiah is called Isidore Isou?” — is less ludicrous when seen as a response to the calculated extermination of European Jewry. “I will create,” he proclaimed, “the ambition, the blazon and the armor of my race, and it will be ennobled.” In a subversion of Aryan values, he anointed himself “Isou the Jew.” For the project of annihilation could not be complete if one Jewish name lived on; those who had killed the people of the book, either with their own hands or through their silence, would have to acknowledge him.

Almost five years to the day from that fateful pogrom, on January 21, 1946, Isou’s improbable plan was put into action when, having arrived in Paris several months earlier, he stormed the stage during the premiere of Tristan Tzara’s La Fuite. Tzara had been Isou’s idol (and a perfect mirror: a bourgeois Romanian Jew with an alliterative pseudonym who led the avant-garde), but now it was “Down with Dada, let us speak of Lettrism!” With the papers delightedly scandalized by his howlings, Isou went from being a stateless Jew who was surviving thanks to a combination of charity (Zionist flophouses and soup kitchens), prostitution (elderly British ladies paying a few hundred francs for “company”), and thieving (which was an art, Isou insisted) to a Left Bank figure with two books contracted to Gallimard. This was truly an astounding feat for someone in his early 20s — even more astounding given that Isou was writing in a foreign language that he barely mastered (and spoke oddly, as can be heard in the voice of “L’Étranger” in his 1951 film Traité de bave et d’éternité [On Venom and Eternity]).

Introduction à une nouvelle poésie et à une nouvelle musique (Introduction to a New Poetry and a New Music, 1947) established the principles of Lettrism, which Isou claimed was “at the avant-garde of the avant-garde,” while L’Agrégation d’un nom et d’un messie (The Making of a Name and a Messiah, also 1947) was a novel-cum-memoir that fictionalized Isou’s formative experiences in Romania (without explicitly naming that cursed land). Because those books, along with the vast body of his later work, from the hypergraphic novels to the 1,400-page La Créatique ou la Novatique (1941–1976) (The Creative or the Novatic, 2004), have long been out of print or difficult to find in the original French (little has been translated into English), Isou remains the least well known of the major avant-gardists of the 20th century. Following upon a major retrospective held at the Centre Georges Pompidou in 2019, Andrew Hussey’s rich biography aims to correct that oversight, providing an engaging, readable narrative of Isou’s multiple dimensions and sprawling ambitions.

After Futurism, Dada, and surrealism, Lettrism was the last of the total avant-gardes to appear, the end stage of art’s decomposition before a new art would arise. Dada had reduced poetry to the word; Lettrism whittled it down to the letter. An alphabet of bodily sounds — hisses and growls, cackles and coughs, snores and sighs — was elaborately systematized to create sound poems that “purified” the form. For Isou, Lettrism was more than invented hieroglyphs and brute noise; it was the starting point for a creative methodology that would be valid for the plastic arts, architecture, economics, mathematics, medicine, psychiatry, even sex (there are Isouien methods of kissing, of fucking, even of masturbation). An elaborate jargon — méca-esthétique, esthapéïrisme, art infinitésimal, cadre supertemporel, polythanasie esthétique, and so on — provided a veneer of intellectual heft to the impenetrability of Lettrism. While a number of disciples moved in and out of the group over the years, it was in many respects a closed shop with Dieu-Isou (God-Isou) at its absolute center.

Hussey seems to be frankly torn about the intellectual value of the entire project. Of Isou’s first book laying out Lettrist principles, he writes: “[F]or most readers, including assiduous followers of the latest avant-garde trends, the book was convoluted, fragmented, and largely unreadable when it was not incomprehensible or possibly even insane.” Of the series of new alphabets Isou invented: “They seem like the obsessive creation of a madman.” Of the hypergraphic novel Jonas: “[I]t is a work produced by someone who knows that he is unwell, possibly quite mad.” Of the 1976 novel L’héritier du château (The Inheritor of the Castle), a sequel to Kafka: “In truth the book is a discordant mess […] a visceral and disturbing account of a mind in free-fall.” Isou had indeed suffered a psychotic breakdown during the revolutionary fervor of May 1968 — he was convinced that the uprising was indebted to his postwar theories about youth culture and even attempted to have himself proclaimed its leader — and spent the latter part of his life in and out of mental hospitals. But the madness inherent in the entire project of Lettrism was there from the start, only it was a calculated response to the rationality and order that had spawned the Shoah.

Hussey has no doubts, though, about the rollicking tale of Isou’s life and times. Born in 1925 in the provincial city of Botoşani, in Romania’s northeast, Isou settled in Bucharest with his well-off, assimilated family. As a precocious teenager he immersed himself in the capital’s Jewish literary circles. After the war, Isou crossed a continent in ruins to get to Paris (for a while, he wondered if he should go to Israel, but since Paris was the absolute center of world culture, he decided that was where he needed to be). His charisma, good looks, and unbounded confidence won him a gang of devoted admirers. He managed, as a stateless Jew barely out of his teens, to secure meetings with Jean Paulhan, Gaston Gallimard, Jean Cocteau, and André Gide. When his genius was not immediately recognized, threats were issued: “Each generation brings with it a mass of new values which old bastards like you try to stifle. I’m warning you now that my friends and I will come and smash your faces in if you don’t publish my work which will create great upheavals. I do not salute you, Isidore Isou.” He accosted movie producers to get his then-unfinished Traité de bave et d’éternité screened at the Cannes Film Festival (that film announced the start of “discrepant” Lettrist cinema, which cut the tie between the image and language, influencing Jean-Luc Godard and Stan Brakhage; it also brought Guy Debord into the Lettrist ambit before an acrimonious break). Isou and his band physically attacked an orphanage to free a young admirer; another scandal involved a Lettrist priest taking the microphone during Mass at Notre-Dame to spout an anticlerical screed. Orson Welles was reduced to an earnest, aw-shucks Midwesterner when Isou and some Lettrist pals recited a sound poem for a BBC documentary on Saint-Germain-des-Prés.

At times, the scandals and adventures so captivate the biographer that Hussey does no more than renarrate Isou’s own tellings of those exploits. Yet Isou could hardly be taken for a reliable narrator — and he was upfront about that: when an editor at Gallimard asked him to change the ending of a chapter in L’Agrégation, Isou demurred, saying that he would not add yet another lie to a story already full of lies. Despite admitting that it is impossible to separate the “real” from the “fantasies within fantasies” in Isou’s writings, Hussey treats Isou’s own work as “a true document of his life and era; a precise eyewitness account” (this of L’Agrégation, a novel creating the myth of a character named Isidore Isou) or a “true account of what Isou had lived through and seen” (of an “erotic novel” set in a mental hospital). The mistake is compounded when considering the book’s inconsistencies and errors, from minor things like dates (the nonaggression pact between the Soviet Union and Germany was signed in 1939, not 1938; Guy Debord and Isou were not “close friends” in the 1940s, as the third line of the book has it, having only met in 1951), names (it is “Mihai” Eminescu, not “Mohai”), and geography (the city of Oradea is in the plains and hills, not the mountains; there could not possibly be a night train going the 40 kilometers from Constanţa to Mangalia) to larger errors in cultural history (Paris, liberated a year earlier, was not in the midst of the épuration sauvage when Isou arrived in August 1945; to state that “five of the original founders of Dada in Zurich were Jewish exiles from the same part of Romania as Isou” is wildly off since only two Romanian Jews were among Dada’s founders and one of them came from Bucharest). When writing about Romania, Hussey relies on accounts in translation or by foreigners; original sources are largely missing (I counted four in seven chapters).

Whatever the documentary faults of Hussey’s book, his subject is riveting, and he tells the tale well. Isou was that rarest of things, a sensitive soul who remained stubbornly convinced of his genius and asserted his right to venture into any field of thought, without a care for traditions or established principles. Some of the results were, as Hussey freely concedes, off the mark, but there was a freedom to Isou’s mind that strongly rebuked the culture of experts and rationality that had once decided utopia would be Judenfrei. If Paul Celan, a fellow Romanian Jew whom Isou befriended in Paris, answered in his own way Adorno’s famous remark about the fate of poetry after Auschwitz, Isou’s whole way of being — with its madness and delirium, its wild excesses, sexual energy, disaggregation, and decomposition — was its own form of justification. In a world where “no one is master of his destiny,” as Isou put it in Traité de bave et d’éternité, where the idea of dying peacefully in one’s bed is a fairy tale since violence surrounds us all in this inhospitable world, the only thing left is creation — unbounded, godlike creation.

¤

LARB Contributor

Marius Hentea is a professor of English literature at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. Born in Romania, he grew up in Indiana and holds degrees from Columbia (BA, political science), Harvard (PhD, government), and Warwick (PhD, English). He is the author of TaTa Dada: The Real Life and Celestial Adventures of Tristan Tzara (2014), which has been translated into German and Romanian, and Henry Green at the Limits of Modernism (2014). His work has appeared in Modernism/modernity, MLQ, and PMLA, among other venues. He is currently working on a book about the trials of authors for treason after World War II.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Under the Language: A Conversation with Pierre Joris on Paul Celan

David Brazil interviews Pierre Joris about his new collection of Paul Celan writings, “Memory Rose into Threshold Speech.”

An Experimental Biography: John Schad’s “Paris Bride: A Modernist Life”

Is John Schad’s family archive as fictitious as, say, Clarissa Dalloway? And does it matter?

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!