Lousy Listing: On “Sight & Sound” and Taste

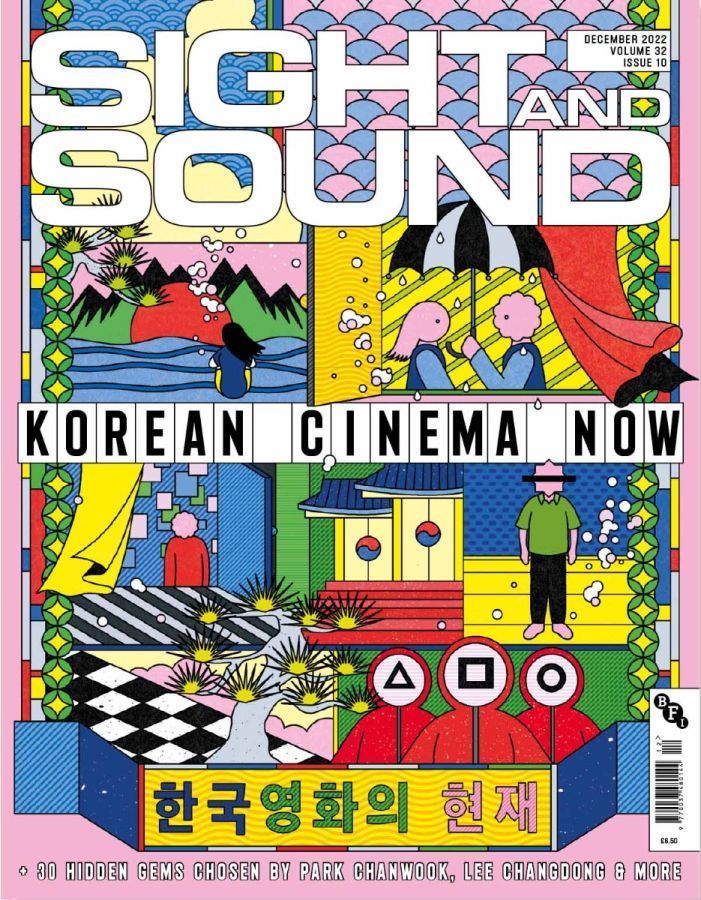

Brian Jacobson gives historical and cultural context to the “Sight & Sound” Best Of poll.

By Brian R. JacobsonDecember 2, 2022

IN THE FALL of 1952, Sight & Sound magazine asked 85 film critics to select “the Ten Best Films of all time.” Critics sent back lists, and in the year’s final issue, Vittorio de Sica’s 1948 Bicycle Thieves was declared the winner. The victory confirmed the film’s place in a pantheon of European art cinema whose remarkable staying power continues to define good taste in movies today. Though triumphant, however, its victory was anything but. In fact, very few of the respondents considered Bicycle Thieves the “best” film. Only 25 out of 63 had included it on their lists, and of the 47 critics whose selections were reproduced in the magazine, only one ranked it first — because the list was in alphabetical, not qualitative, order. André Bazin and Paul Rotha each had it in 10th, and the vast majority — including Iris Barry, Lotte Eisner, Siegfried Kracauer, Henri Langlois, and Karel Reisz — didn’t include it at all. No other film appeared on even 20 lists, and those on as few as five — less than one percent of the films named — still eked out a place among the notable runners-up. The critics had spoken … but had they?

The question is back on the table this month with the release of the latest edition of Sight & Sound’s “best of” list, which has appeared every 10 years since 1952. Back in July, I was invited to contribute to the list for the first time and watched closely as a new generation of critics and scholars wrestled with a task that has long teased and tormented the select few asked to do it. “Everybody knows,” as David Lodge once wrote about ranking books, “that ‘best’ in this context is not an absolute and authoritative judgement, but it is not totally arbitrary either.” We rely on experts to turn subjective assessments of quality into near-objective measures of superiority. But in a time when expertise — and who can become an expert, pass judgement, and establish objectivity — has increasingly been called into question, the power and role of ranking exercises like Sight & Sound’s “best of” list deserve as much scrutiny as the outcome of the poll itself.

Film culture’s enduring obsession with list-making has been under fire of late. “Against Lists,” a widely circulated 2019 essay by Elena Gorfinkel, wryly captures everything that is wrong with film lists and the consensus they imply: the predictable repetition of the Western European canon, the consistent exclusion of artists and critics who aren’t straight white men, and the transformation of film culture into soulless counting. Many of these criticisms are as old as the lists themselves but have, like the meager support for Bicycle Thieves’s coronation, been overshadowed by stories of greatness. One of the ironies of Sight & Sound’s role in popularizing film lists is that many of the first contributors hated the idea. If the 1952 critics could agree on anything, in fact, it was that ranking films was a “lousy” exercise from the start. A few simply ignored the invitation, while others mocked the rules or refused to follow them. “Why not 50?” one critic asked, or “Why not 2 1/2?” joked another. Never one to do things the official way, Langlois sent a list of eight topped by a set of shorts: “Chaplin’s 1916 films.” Lindsay Anderson, who sent 16 titles, admitted to cheating, but “isn’t the question itself,” he parried back, “a bit of a cheat?”

At best, choosing the greatest films was “impossible” or just plain “silly.” At worst, it was “disturbing” or even “barbarous.” “What a thing to ask[!]”

Why do we keep doing it? Sight & Sound’s interest is easy enough to spot: lists set trends and sell magazines. In the age of endless streaming options and download-on-demand, they make easy content and good clickbait. Listicles are low-hanging fruit; harder to dismiss are the many other film lists we studiously create and consult all the time. Syllabi are lists too, after all, as are the screening programs and playlists that shape so much of film education and cinephile culture. This curated form of list-making warrants scrutiny and skepticism and must be taken seriously for its powerful role in shaping cinema’s canon, culture, and commerce, not to mention many people’s daily film experiences. But still, these top 10s help us decide what to watch first or what we must watch before it disappears … or, perhaps, how to game the algorithm so it doesn’t. Lists order our thoughts and clear our minds. They make large things smaller and more manageable, narrowing down the endless possibilities. They cut through the clutter and get to the point. They are symptoms of critical stagnation in the dominant film culture, or, if you happen to be one of its adherents, evidence of critical consensus.

It is worth recalling that Sight & Sound’s list emerged with Europe’s midcentury art film institutions: festivals, archives, magazines, and international networks of artists, critics, and academics whose critical consensus we’ve been left to grapple with. Part of the list’s aura is its connection to that remarkable moment and the platform it gave to new forms of film culture, including the rare exceptions — one might think of Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (11th in 1962; 6th in 1992; 41st in 2012) — to the list’s white European rule. That connection should remind us of something the list effaces: the midcentury promise, partially fulfilled in the work of the women and non-Western filmmakers whose films win festival prizes and critical acclaim today, that an inclusive international film culture might come to define art cinema.

This “awful” idea of the Sight & Sound poll could be blamed most immediately on one of those art film institutions: the Festival Mondial du Film et des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, which had first posed the question of greatness earlier in 1951 to 100 filmmakers. Their list had Bicycle Thieves in third, with Battleship Potemkin carrying the day. Like the critics, though, the directors, even those whose films made the lists, expressed misgivings about the whole enterprise. René Clair, who declined to participate, argued that filmmakers were the wrong people to ask. Artists might, after all, be their own worst critics. But while some may have been hiding behind false modesty, others were perfectly positioned to recognize the stakes of treating their films and peers in this way. Challenging the idea that such lists should establish enduring canons, Jean Cocteau, for example, insisted they were better created as café banter, with the titles scribbled “on the corner of the table” and left, he implies, to be cleared away with the dishes.

Sight & Sound readers, first unsolicited, then at the magazine’s request, sent in their own lists. Perhaps unsurprisingly, they sided with critical taste — canon formation in the blink of an eye — again crowning Bicycle Thieves with 64 votes. Five years later, the Belgians repeated the exercise at Expo 58 (another win for Potemkin). Not to be outdone, Cahiers du Cinéma ran an “auteurist” version of the poll, with the 10 greatest directors ranked in the first round, followed by a list of the best films by those making the cut (F. W. Murnau’s Sunrise won, with Ivan the Terrible replacing Potemkin as Eisenstein’s best film and de Sica failing to break the top 10). Sight & Sound repeated the exercise in 1962 and has continued to do so every decade since.

When they ran the list the second time, Sight & Sound’s editors defensively admitted that objectivity was neither possible nor the goal, a refrain heard every decade after. It took much longer for the magazine to take seriously the startling absence of women and non-Western filmmakers, while acknowledging, as film historian Ian Christie did in its pages in 1992 and 2002, their list’s role in bolstering a canon that had rightly been under attack for decades.

Lists are formed by inclusion but always end with exclusion. Among the salutary effects of the Sight & Sound list is just how visible it makes the process through which a minority of voices excludes minority voices. The sheer smallness of the numbers, with their skein of objectivity, makes it so staggeringly plain. It only took 22 people to crown Citizen Kane the best film of all time in 1962, and none of them needed to have thought it was the best film.

A decade ago, Vertigo made headlines by unseating Kane, which had held the top spot for 50 years. But Kane still ranked second, and the top 10 remained reliably familiar: it included Rules of the Game, which has been on every list; The Passion of Joan of Arc, which made the list in 1952 and has moved on and off every other decade; and The Searchers, runner-up in 2002 but otherwise on the list since 1982, when 8 1/2 also joined. Tokyo Story, another rare non-Western outlier, and 2001: A Space Odyssey both joined in 1992, while Sunrise, winner of the 1958 Cahiers list, made the Sight & Sound list comparatively late, in 2002. Only Dziga Vertov’s 1929 Man with a Movie Camera was new to the top 10 in 2012, while Potemkin narrowly missed out for the first time in the list’s history.

In short, nothing much changed, despite the fact that Sight & Sound’s editors had made an effort to shake things up, in part by radically expanding the list of voters from the long-standing target of 100 critics (145 in 2002) to more than 1,000. Vertigo now needed to appear on 191 lists to win, while 8 1/2 made the top 10 by appearing on just 64 out of 846 submissions. I find these numbers fascinating for what they tell us about how differently things might have looked under slightly altered circumstances. Take, for instance, Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce 1080 Bruxelles (on my list this year), the highest ranked film directed by a woman, which tied for 35th place. It garnered 34 votes, 30 (three percent) away from making the top 10. Can a film like this — or Claire Denis’s Beau Travail (also on my list; 78th in 2012) — break through this time?

There is reason to think that change may be in store. Sight & Sound has taken steps to generate a different kind of list this year by again expanding (to more than 1600) and transforming its list of list-makers. Rather than leaving it to the “chains of recommendations” that shaped the 2012 list, this time, consultants were hired. Will it make a difference? I spoke to critic Girish Shambu, one of those hired to consult, who doubts we’ll see much change at the top. But he also voiced another common argument: that changing the top of the list shouldn’t be the goal anyway.

The real interest lies down-ballot, where an emerging counter-canon had already begun to take form in 2012 — with films such as Jeanne Dielman, In the Mood for Love, Sátántangó, Beau Travail, and Touki Bouki — and has continued to percolate on the other lists that now define much of the Sight & Sound website. Whatever else they might find in the first 10, the interested student or cinephile will still find alternatives to the old canon by digging deeper into the top 100 or by exploring films by the directors who now fill Sight & Sound’s annual best-of lists. The 2021 list, for example, leads with films directed by Joanna Hogg, Céline Sciamma, Hamaguchi Ryūsuke, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and Julia Ducournau; in 2020, it included Steve McQueen, Kelly Reichardt, and Tsai Ming-liang.

Scanning through decades of old lists in the Sight & Sound archive also yields the occasional treasure: windows into the minds of critics and directors, or rare cases, especially in the early days, when wonderfully unorthodox choices found their way in. There’s Nicole Védrès’s Paris 1900 on a 1952 list, or the fact that Robert Flaherty’s Louisiana Story (not Nanook of the North) stood out as his best work, or Bazin, anticipating (or all but ensuring?) Olivier Assayas’s obsession with Louis Feuillade’s Les Vampires.

The argument for lists is the promise that they still might do those things Gorfinkel believes, for good reason, they won’t: save overlooked films, write new film histories, and establish new canons. Against all odds, there remains something powerfully utopian about identifying and recognizing greatness, with its promise that we might get it right for once, and that, in doing so, we may yet tap into the prestige it grants and reorient the narratives and debates it creates.

That promise has been on my mind since July, when invitations went out to the critics and directors whose choices will determine if this year’s edition looks any different. As always, the task is too big, its parameters too vague, and its measures too subjective. On social media, cynicism grows, and the jokes pile up: why not vote for the worst 10 (as one Sight & Sound reader first proposed in 1952), or choose only Bond films, or just rank the Marvel universe? Eyes roll, followed closely by the heads symbolically lopped off of lists past. In the end, though, most people still submit their lists, whether earnestly hoping to tip the scales or, more cynically, craving the prestige that somehow passes from great works to those who get to call them great.

Sight & Sound has turned Cocteau’s café debates into a scaled-up pseudoscience, but list-making is better understood when disaggregated back to the individual level, where every list stitches together stories cut from film fragments. Making a list, as I learned when I finally sat down to face the impossible task, requires rifling through one’s memories, pulling from a personal history of movies and viewing experiences — Play Time in 70mm, Portrait of Jennie in nitrate, the bus ride home after Le Mépris, and all those classroom films that changed everything: Meshes, (nostalgia), Dil Se.., Cléo …

The list goes on and on, an unspooling reel of moving memories. Every critic’s list, however objectively composed and recompiled, starts as a collection of one’s own film history, and list-making is the work of its recollection. As Walter Benjamin, one of history’s great list-makers, put it, when the collector speaks to you about his collection, “he proves to be speaking only about himself.”

What does your list say about you?

¤

Editor's note: The 2022 list has since been released and can be viewed on BFI’s site.

¤

LARB Contributor

Brian R. Jacobson is author of Studios Before the System (Columbia University Press, 2015) and professor of visual culture at Caltech.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The East Village Detective: On Bill Morrison’s Historical Poetics

Seth Fein considers Bill Morrison’s latest, “The Village Detective: A Song Cycle,” in the context of the filmmaker’s body of work.

Binge and Purge: The Rise of Extreme Film Criticism

Noah Gittell considers the growing phenomenon of “Extreme Film Criticism” in the wake of media conglomeration and the decline of long-form journalism.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!