Lost Men, Found Women: Revisiting the New Hollywood

Nancy West engages in a feminist “anti-retrospective” of the cinema of 1972.

By Nancy M. WestApril 13, 2022

IN A DARK OFFICE pulsing with sin and secrecy, a young wife, Kay, confronts her husband. “Is it true?” she asks. A pause follows. “No,” he lies. Sighing with relief, Kay leaves the room to make them a drink, shaken but smiling. As she gets out glasses and pours ice — an ordinary housewife once more — she sees three men enter the office. Two of them anoint the husband with a kiss of the hand. Another one closes the door, his act as absolute as a bump-off: Kay will play no role in her husband’s affairs, now or ever. She stands there alone, looking on hopelessly as a final wipe turns the screen black.

The sequence above is from Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather, which turns 50 this year. Like so many movies of the New Hollywood, that brief, mythical era celebrated for its innovative filmmaking, The Godfather flaunts a masculinist ethos from first frame to last. As a film lover, I cannot resist the movie for its epic strength or Marlon Brando’s mellowed performance, the way he plays Don Vito with an almost courtly reserve. And countless times, in scores of film classes, I’ve praised The Godfather’s exploration, vis-à-vis Michael Corleone, of New Hollywood’s Master Theme: the “lost” American man, young, defiant, soulless.

But when I think of Kay’s spiritless role and how it wastes the radiant talent of Diane Keaton; of Coppola’s initial refusal to give the part of Connie to Talia Shire because he thought her “too pretty”; of The Godfather’s total dismissal of a female viewpoint; and of the film’s retreat to 1940s America while ’70s feminists were out in the streets, I grow impatient with all the nostalgic retrospectives surrounding the New Hollywood. Who cares if The Godfather is turning 50? Let someone else pay tribute to it and the hairy, masculinized New Hollywood it represents.

And yet … that final shot of Kay keeps coming back to me, insisting I revisit the era.

It turns out others are rethinking the New Hollywood, too. Within the past four years, a corps of writers has begun to reassess the period, exposing its elisions and biases, fetishes and abuses, and bringing female talent to the fore. Streaming dominance, which brings to light many a forgotten film, enables them. Social movements like #MeToo and Black Lives Matter fuel their interventions. And the wistful New Hollywood retrospectives, based as they are on troubling foundations, piss them off.

Maya Montañez Smukler, Nathan Abrams, Gregory Frame, Cary Edwards: this new wave of scholars takes aim at auteurism, that consecrated mainstay of New Hollywood, writing which treats the director as the true artist and unifying voice of a film — the king of the castle, master of his domain. Emphasizing how auteurism favors a pet coterie of white male directors, Smukler, et al. swerve the spotlight toward other folks, such as production designers and female directors. These scholars also question the narrow criteria by which a film makes it into New Hollywood. “Gritty realism” becomes less a defining feature than a fetish, “1967” less the start of an era than an arbitrary date. Reading their stuff, you can’t help but feel New Hollywood’s ground shake under your feet.

Smukler’s Liberating Hollywood (Rutgers University Press, 2019) shows how feminist reform efforts in the 1970s led to a noticeable rise in the rank of female directors. Yet this is no simple story of triumph. On virtually every page, Smukler demonstrates how Hollywood’s institutionalized sexism created obstacles for women. The book begins by charting their attempts to reform Hollywood, including the founding of the Writers Guild Women’s Committee in 1971 and the discrimination lawsuits they waged against the industry. From there, Smukler chronicles the frustrations and hard-won achievements of her 16 directors. We read how Claudia Weill won success on the art-house circuit for her independent features, while Stephanie Rothman, working under B-movie king Roger Corman, tried to script feminist messages into male-fantasy flicks. We discover how Elaine May suffered at the hands of male producers and feminist watchdogs. We also learn about inspiring husband-wife partnerships, such as Raphael Silver’s support of his wife Joan Micklin Silver on her first feature, Hester Street (1975), and Joan Rivers’s collaboration with her husband, Edgar Rosenberg, on Rabbit Test (1978). Smukler, however, is quick to recount the sobering parts of Rivers’s experience, such as her hiring of veteran cinematographer Lucien Ballard. Rivers “had hoped Ballard would be her mentor.” “Instead,” she testified, “he was a mean son of a bitch.” Zigzagging between positive and dismal accounts gives Smukler’s book a mercurial rhythm, instilling in the reader a deep admiration for the women she spotlights — and a wish to go back in time and smash their male colleagues’ cameras. Or heads.

Nathan Abrams and Gregory Frame’s New Wave, New Hollywood (Bloomsbury, 2021) features 10 essays that reinvigorate our sense of the era. The collection contains some unexpected topics, like New Hollywood’s eclipse of the L.A. Rebellion and Taxi Driver’s influence on Trumpian politics. Here and there, the book also dusts off a ’70s classic. Cary Edwards’s essay, for example, reconsiders two cornerstones from 1971: The French Connection and Dirty Harry. Charting the history of their critical reception, Edwards shows how the former has come to represent a revolutionary, risk-taking new Hollywood, while the latter has typified a reactionary, old Hollywood. Edwards isn’t having it. Dirty Harry, he argues, is a complex, ambiguous film that splits our identification between Harry Callahan (Clint Eastwood) and his killer-antagonist, Scorpio (Andy Robinson). After reading Edwards’s essay, one can’t help but question the binaries that separate New and Old Hollywood or wonder about the canon’s supposedly leftist ideology.

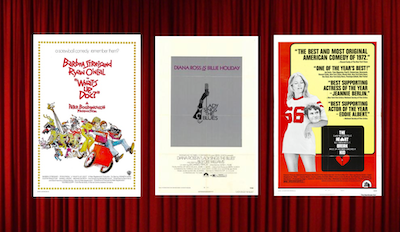

Inspired by this writing, I decided to revisit four films from 1972. Each movie was a box-office smash and critical favorite in its time — and yet, when it comes to New Hollywood criticism, remains a picture non grata. Each makes ample use of female talent onscreen and off. Each spoofs, or spurns, New Hollywood’s theme song of lost, young men. And each reveals a rich exchange between films inside and outside New Hollywood, reminding us that 1970s cinema was a far messier affair than critics would have us believe.

Retrospectives generally revisit the past with nostalgia, singling out one artist as they cast him within an idealized context of freedom or rebellion. Overwhelmingly, they focus on men. Consider this an anti-retrospective.

¤

A screwball comedy harking back to classics like Bringing Up Baby, What’s Up, Doc? also turns 50 this year. It’s the story of Howard Bannister (Ryan O’Neal), a flustered musicologist, his uptight fiancée, Eunice (Madeline Kahn), and Judy Maxwell (Barbra Streisand), a charming swindler who pursues Howard with anarchic force. Like all screwball comedies, What’s Up, Doc? is female-driven, a relief from testosterone-charged movies of New Hollywood. O’Neal, fresh off Love Story (1970), takes backstage to Streisand and Kahn. The result is pure girl power: Judy Maxwell is Streisand’s freest and most charismatic role, to which she brings her musical talent and Brooklyn-Jewishness. And Kahn imparts her own style of comedic wildness to the potentially thankless role of strait-laced fiancée.

Offscreen, a third woman, production designer Polly Platt, brilliantly influenced What’s Up, Doc?. Late last year, Aaron Hunter published Polly Platt: Hollywood Production Design and Creative Authorship (Palgrave Macmillan, 2021), in which he charts Platt’s substantial contribution to the look of New Hollywood cinema through films like The Last Picture Show (1971) and Thieves Like Us (1974). Hunter’s book is an eye-opener, depicting production design as a collaborative role that cuts across every department from locations to costumes to script. In the 1970s, it was also an underappreciated and underpaid job. Is it a surprise to learn, then, that the wives of several New Hollywood directors took on the role? (We might mention here Bob Rafelson’s wife, Toby, who created the exquisitely tacky look of The King of Marvin Gardens, which also turns 50 this year.)

It turns out Platt chose What’s Up, Doc?’s San Francisco setting; the city serves as a major character in the comedy. Critics spotlight on-location shooting as one of New Hollywood’s signature features, but they rarely consider those in charge of locales. Platt convinced Peter Bogdanovich, the film’s director and Platt’s ex-husband, to shift the location from Chicago. “I didn’t want to see the character Streisand was playing: an irresponsible and impossible creature, in Chicago with her Brooklyn accent. I wanted to get her out of the East Coast, where the character could be an outsider,” Platt explained. She visited Seattle, Dallas, and Houston before landing on the city by the bay. It’s a “make-believe town,” she told Bogdanovich the night her plane landed. She and location manager Frank Marshall spent three weeks driving around the city, plotting out the route for the film’s famous chase sequence, making sure the city’s narrow alleys and bounding hills were played for maximum absurdity.

Platt also masterminded What’s Up, Doc?’s witty costume design. She put actress Mabel Albertson, in her 70s at the time, in hot pants. She dressed O’Neal and Ryan in complementary colors, subtly suggesting their sympatico. And she accented the differences between Kahn’s po-faced Eunice and Streisand’s free-spirited Judy through every outfit. Platt put Kahn in spotless white gloves and four strings of pearls, a conspicuously synthetic, bouffant wig, and dresses that look upholstered onto her, making Eunice a cross between a Jackie O wannabe and a sofa. She deliberately carries none of the sexy, liberated appeal that Streisand’s Maxwell does, with her newsboy cap, low-cut tops, and bell-bottom jeans.

Most importantly, it was Platt’s inspiration that made Judy Maxwell into one of American cinema’s precious few heroines from the 1970s. In the original script, Judy was a tough-talking, thieving dame. Platt convinced Bogdanovich to scrap the idea and make the character more lovable. She also suggested to her ex that Maxwell not be the nag to O’Neal’s crafty operator, as the original script had it. Instead, she advised that he make the man the nag. From that moment on, What’s Up, Doc? fell into place.

¤

Lady Sings the Blues, a biopic of Billie Holiday starring Diana Ross, has never entered the hallowed halls of the New Hollywood. No surprise there, given how writers have framed the period. Almost all studies reveal a giant blind spot when it comes to Black cinema, even though the 1970s witnessed a flowering of Black films. What’s more, these accounts betray their writers as genre snobs. The biopic is “the most hated of all genres,” decried as shallow and formulaic, according to Deborah Cartmell. But biopics can contain surprising complexities, and Lady pushes the genre’s norms, particularly in this moment. Taking drug addiction as its subject matter, it features a Black female protagonist and puts R&B diva Diana Ross in the lead role.

The film was the brainchild of Berry Gordy, the Black, charismatic, can-do founder of Motown. As Wil Haygood describes in Colorization (2021), his history of Black cinema, Gordy broke into the film industry — where the upper, middle, and lower echelons were all white — by assembling his own team of Black filmmakers and performers. Producing Lady was a huge gamble on Gordy’s glittery reputation as a music mogul — and on the Motown brand. At 43, Gordy had a lot to lose, unlike, say, Coppola or Martin Scorsese, who were barely out of film school when they broke into Hollywood.

Gordy’s hottest property in the early 1970s was Diana Ross, and what he wanted for her was a star vehicle. Knowing that the biopic can launch a star faster than almost any genre, he lit on the idea of producing a film about Holiday. In his mind, Lady would make Ross a Hollywood darling, maybe even land her an Oscar. (Biopics may not always be a critical favorite, but they are an Academy darling, providing the clearest route to a Best Actor/Best Actress nomination or win.)

“I love it,” Pauline Kael wrote on her notepad after seeing Lady. In her review, she’d grumble about the film’s clichés and distortion of facts, critical of how it cleaned up the disorder and dissatisfaction of Holiday’s romantic life. But she praised the film for delivering “emotional power” and “great quantities of personality.” Impatient with the consciously avant-garde spirit of many New Hollywood films, Kael appreciated Lady’s unapologetic appeal to the masses — its dramatizing of stardom, its “pop” values and themes, its showcasing of Ross. The film “wants you to have a good time,” she wrote, her relief almost palpable.

Critics Vincent Canby and Roger Ebert also lavished Lady with love, noting Richard Pryor’s acting range and applauding the male lead, Billy Dee Williams, who plays Holiday’s heroic husband, Louis McKay. Almost overnight, the role of McKay made Williams into a leading man and crowd puller, a veritable “Black Clark Gable.” Williams’s classic brand of stardom, and McKay’s too-good-to-be-true characterization, couldn’t be more at odds with the scrappy performances and lost-men figures of the New Hollywood. And why wouldn’t this be the case? In the 1970s, Black filmmakers wanted to feature figures of empowerment, not weakness. (Recall Shaft’s opening sequence, which shows its hero strutting across five lanes of traffic, passing marquees that blare the names of Walter Matthau and Robert Redford, as if to suggest a new cinematic era of hip Black men has arrived.)

But it’s Diana Ross, and her inhabiting of the Holiday role, that dominates Lady Sings the Blues. As the opening credits roll, we see Ross’s expressive body framed by footage that periodically freezes into film stills, a technique that in its gesturing to movies like The Wild Bunch, reveals the crossover between films within and without the New Hollywood canon. When Ross gets thrown in jail for drug possession, we see her body wracked from withdrawal. Two custodians fingerprint her, then lead her to a cell. Filmed at high angle, Ross lets out a high, lonely shriek as she flings herself against the cell walls. It’s a scene of total and unbroken anguish with no build-up. Just minutes into Lady, we understand that this isn’t merely the debut of a Top 40 singer: this is acting.

Over the film’s course, Ross plays Holiday as a gangly adolescent, a professional at the top of her game, and a strung-out performer whose childlike confusion breaks your heart. In a cinematic landscape overrun by male characters, she aims to give depth to a Black woman and key cultural figure. At a nightclub, we watch Ross struggle to sing “The Man Who Got Away” while men grope and razz her — and then blaze into confidence when they finally pay attention. Later, we see Ross wrestle a heroin needle from Williams, who is horrified when she pulls a knife on him, her face savage with need. In another scene, a stoned Ross and Pryor weep over the death of Holiday’s mother. Their acting is a brilliant jumble of halting gestures and unfinished sentences, revealing that other actors besides Hoffman and De Niro knew how to deploy the intuitive, emotion-based techniques we associate with method acting. Ross is scat-fast with comic lines, inventive in her lyrical use of dialogue. When she performs Holiday’s songs, we behold a strange alchemy. Looking uncannily like Holiday, Ross evokes the great jazz singer while being every bit herself.

¤

Genius. Maverick. Rebel. Such descriptors pervade New Hollywood discourse, emphasizing the dare of its filmmakers. After watching The Heartbreak Kid, a film bursting with originality, I’d just as quickly bestow those adjectives on Elaine May, actress, screenwriter, and, as The Criterion’s David Hudson writes, a “criminally underappreciated moviemaker.” May specializes in dark comedy, using it to mock her male characters as shallow, vain, and pathetic. In the three films she made during the 1970s, the “lost man” motif is played as a joke, men blunt objects of egotism. What’s more, these films reveal how May, even as a novice director, absorbed and revitalized New Hollywood’s cinematic language.

Elaine May got her professional start in the late 1950s working with Mike Nichols, the comedian turned filmmaker who, as director of The Graduate (1967), is a New Hollywood papa. Critics have long celebrated The Graduate as a dark satire of middle-class values, but they neglect to point out how The Graduate emerged from Nichols and May’s comedic routines. Between 1957 and 1961, the duo revolutionized comedy by delivering smart social commentary to crowds of intellectuals, college students, lesbians, and gay men, the very audience critics identify with New Hollywood. Nichols and May’s comedy targeted middle-class, suburban life and the new intellectual culture they saw growing around them. Young Americans, they pronounced, were taking themselves too seriously — a sentiment that hints at the best way to see May’s films: as sendups of the mirthless, sometimes mediocre, movies her male counterparts were directing.

In 1968, after signing a contract with Paramount, May became the first female director with a Hollywood deal since Ida Lupino. Even more extraordinary, Paramount gave May a three-base hit as director, screenwriter, and lead actress for her debut film, A New Leaf (1971). But Paramount’s move, Maya Montañez Smukler tells us, reeked of exploitation. It saved Paramount money (May got $50,000 for all three films while Walter Matthau, her co-star, raked in $350,000 for one), while capitalizing on May’s position as a woman in the industry. Paramount’s producers all proved to be chesty, arrogant meddlers, muscling in on her script, leaving her furious that she couldn’t get the artistic prerogative enjoyed by her male colleagues. She quit the studio, then sued it. By the time she did The Heartbreak Kid, May was a director for hire with more autonomy and a surer vision. “[W]ith this second feature,” Stephen Farber wrote for The New York Times, “Elaine May becomes a major American director.”

The Heartbreak Kid tells the story of Lenny Cantrow (Charles Grodin), a Jewish New York salesman who falls in love with Kelly, a Nordic goddess from Minnesota (Cybill Shepherd) while on his honeymoon with Lila (Jeannie Berlin). Upon its release, critics raved about how May delivers queasy comedy that slides into savage terrain. “It’s a comedy,” wrote Roger Ebert, “but there’s more in it than that; it’s a movie about the ways we pursue, possess, and consume each other as sad commodities.”

Like many New Hollywood directors, May was willing to improvise, to indulge and exploit the stylistic oddities of her cast. This observation goes especially for Grodin and Berlin. We discover their quirks (Grodin’s deadpan delivery, Berlin’s nasal inflections) through May’s insistent use of closeups, long takes, and the way she fiddles with Neil Simon’s script to create wandering-around dialogue (hallmarks, all three, of the New Hollywood). May’s strategies work overtime in the scene where Lenny tells Lila he wants a divorce — on the fifth day of their honeymoon, over a lobster dinner. Building the scene around Grodin’s and Berlin’s facial expressions, May holds Lenny and Lila claustrophobically within the frame, trapping Lenny with the very woman he wishes to escape. Grodin, palavering about “new starts,” insisting they order the key lime pie for dessert (presumably to soften the blow), and telling Berlin she can have the car, plays the scene for comedy. But Berlin plays it for comedy and heartbreak. The effect is schizophrenic, plunging us into an atmosphere of turmoil that both evokes the work of John Cassavetes and spoofs it.

Lenny gets Kelly in the end. But at their wedding reception, which closes the film, he walks around aimlessly, making dopey comments to guests. The final shots show Lenny sitting on a floriated couch, humming the hit song “Close to You,” as he stares into space. Referencing countless New Hollywood endings from The Graduate to McCabe & Mrs. Miller, the scene caps off May’s devastating interpretation of romantic love while excoriating New Hollywood’s theme song of the lost man. Poor Lenny, it seems to mock. He brought it on himself. Its sympathies — and mine — are with Lila. I wish she’d took the car and ran Lenny over.

¤

And what of that other big film of 1972, the one that went head-to-head with The Godfather for seven Oscars? Cabaret is innovative in every New Hollywood way, from its frank sexuality to its tawdry aesthetic to its nihilistic revision of the musical. The film also features Sally Bowles, an exuberant, corruptible, bed-hopping singer who tops any worthwhile list of leading ladies in ’70s cinema.

In the movie’s spectacular closing scene, Sally performs the song “Cabaret.” Having just terminated a pregnancy and realized her love affair with Brian (Michael York) is over for good, Sally is back where she started — fabulous as ever but alone, always alone. As she begins singing, we discern her sorrow, catch the falsity behind her grinning delivery. It’s in the way Minnelli halts on a word or exaggerates others, in how her face, with her cherry red lips and unnaturally bright eyes, registers momentary despair. But Sally fights through it all, belting out “Cabaret” with a desperation that is both hers and Minnelli’s, beckoning us with her emerald-green fingernails, making us believe in the “life” of the cabaret because Minnelli comes most alive when she sings. “Cabaret” is a performance of a lifetime, enacted on an isolated stage defined solely by Minnelli’s gestures and a few colored lights. Wearing a purple jumpsuit designed by Charlotte Fleming, braless and platform heeled, Sally Bowles is every bit a ’70s woman: liberated, unapologetic, hungry. The role is a far cry from simpering Kay Adams, stranded in 1940s gangland. Sally may be doomed, but she won’t be shut out.

Hear that, Michael?

¤

LARB Contributor

Nancy West is a professor of English at The University of Missouri in Columbia. She is the author of three books: Kodak and the Lens of Nostalgia (University of Virginia , 2000); Tabloid, Inc: Crime, News, Narrative (Ohio State University Press, 2010); and Masterpiece: America’s Fifty-Year-Love Affair with British Television Drama (Rowman and Littlefield, 2021). Nancy publishes on a wide variety of topics including photography, film noir, film adaptation, and television drama. She is currently working on a memoir entitled Moviemade Girl. It’s a bittersweet account of how she, as a young girl growing up in the violent city of Newark, New Jersey, found escape in the movie-rich culture of 1960s and ’70s New York. Guiding her through that culture was her wayward dad, an unemployed alcoholic with expensive tastes, an aesthete’s sensibility, a penchant for petty crime, and a religious devotion to Hollywood film.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Circle of Love: Remembering Abbey Lincoln in “Nothing But a Man” (1964)

Matthew Eng recalls Abbey Lincoln’s intertwining legacies as singer, actress, and Black radical.

“You Couldn’t Even See”: Genre, “Thomasine and Bushrod,” and the Matter of Black Film

Nicholas Forster explores the question of how to define Black film through a close look at the 1974 film “Thomasine and Bushrod.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!