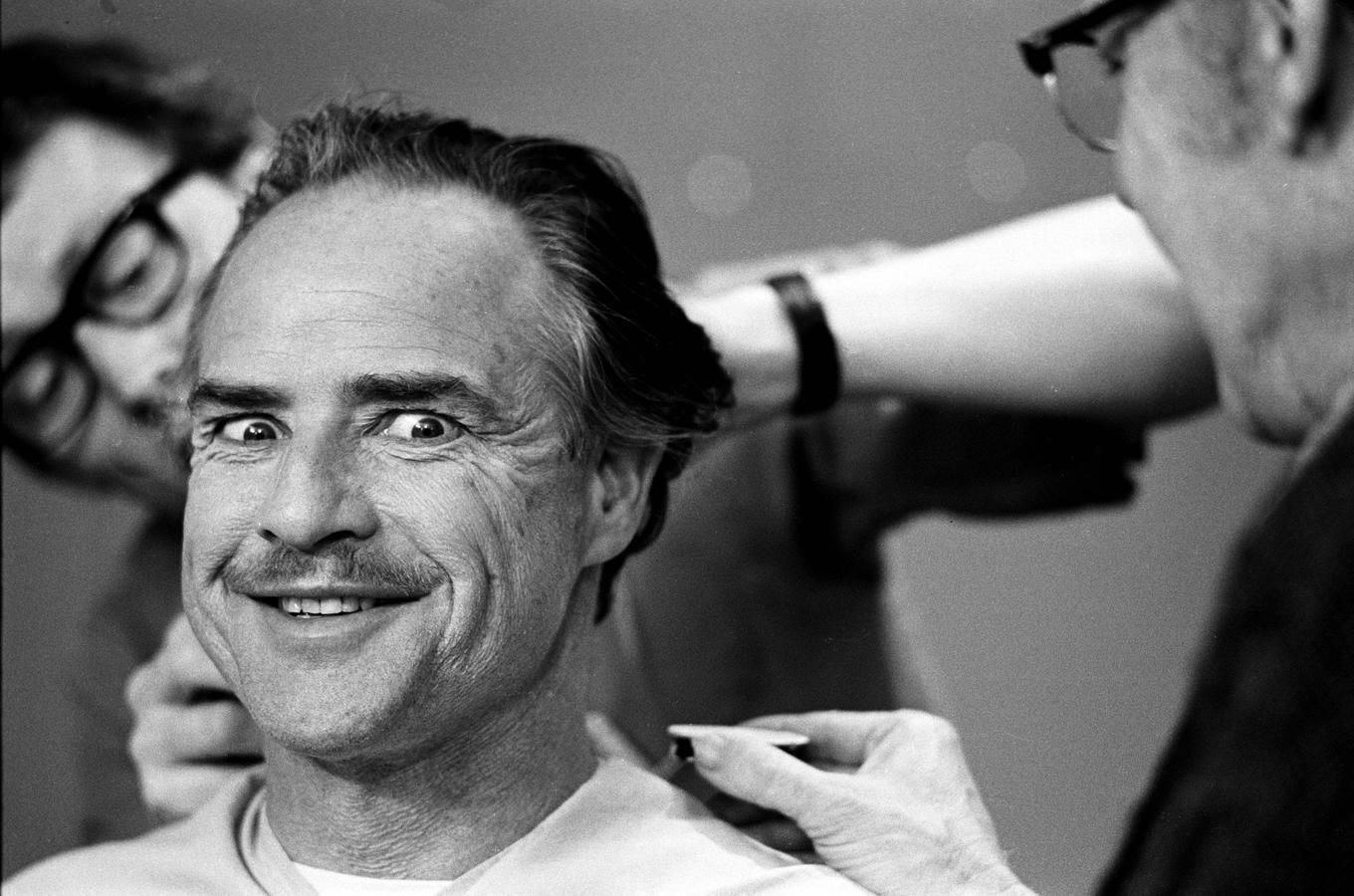

Being Brando

Stevan Riley's documentary "Listen to Me Marlon" is an examination of Marlon Brando, a rare vanity project that arrived 11 years after the actor's death.

By Manuel BetancourtMarch 13, 2016

The principal benefit acting has afforded me is the money to pay for my psychoanalysis.

— Marlon Brando

STEVAN RILEY’S documentary Listen to Me Marlon, shortlisted for the Best Documentary Academy Award, is a probing examination of the towering Hollywood actor, Marlon Brando. Or rather, that’s what it would be if it was not so singularly dictated by the actor himself, making it that rare vanity project that somehow arrived 11 years after the actor’s death. As we learn at the film’s start, Brando “made hundreds of hours of private audio recordings, none of which have been heard by the public until now.” They make up the bulk of the documentary’s voice-over, lending the film an unencumbered feeling of intimacy, as if we were given a chance to overhear Brando’s thoughts. But Listen to Me Marlon functions less as an illuminating portrait of Brando himself than as a document of the import of psychoanalysis and Method acting into America’s cultural lexicon at midcentury.

During the 1940s and 1950s, when Brando cemented his status as perhaps the greatest actor ever to grace American stage and screen, Freud’s theories and Stanislavski’s teachings were flourishing, coming together most readily in the Streetcar Named Desire actor. “Make it real, make it alive, find the truth” — so intones Stella Adler, Brando’s teacher, in one of the snippets of her many TV appearances that pepper Riley’s documentary. That might well be Riley’s own imperative in crafting his film. To “find the truth,” after all, is the impossible imperative of documentary filmmaking. This is no doubt why the film goes to great lengths to create a sense of spontaneity, mimicking the very tenets of Method acting that have taught audiences and actors alike that authenticity is the key to great acting. As David Krasner puts it in the introduction to his edited collection Method Acting Reconsidered, “Authenticity appeals to the inner life construed as an expression or state of the self, offering physical and psychological understanding of identity.” In order to represent the inner life of Brando, Riley stages his film around the idea that the actor’s personal musings are exemplary of the private self that Brando rarely offered up in interviews but that he somehow revealed in his performances.

Spontaneity and authenticity are the hallmarks of Method acting, and, in many ways, they have become the de facto way that we discuss the strengths of a performance. At the time of these recordings, Brando was rallying against the cookie-cutter brand of acting that had long reigned supreme: “Your Bogarts and your Coopers gave you the same performance in every film,” he tells us at one point. The star system all but required it. But with Brando and his explosive Stanley Kowalski, the Method went supernova. In accord with the principles of pop psychoanalysis, Method acting promoted, as Krasner writes, “the idea that there exists a deeper, perhaps subconscious self, one more real than the social self.” In doing so, it fostered one of the greatest shifts in acting technique of the 20th century.

It also gave rise to one of the most longstanding criticisms of Method acting. Harold Clurman — founder of the Group Theatre alongside Lee Strasberg, who later became the director of the Actors Studio where the Method would take shape — took to The New York Times in 1958 to blast the perversion of Stanislavski’s teachings in what he scoffingly referred to as “The Famous Method”:

With the immature and more credulous actor [Method acting] may even develop into an emotional self-indulgence, or in other cases into a sort of private therapy. The actor being the ordinary neurotic man suffering all sorts of repressions and anxieties seizes upon the revelation of himself — supplied by the recollection of his past — as a purifying agent.

Clurman’s words cannot help but apply to the very premise of Listen to Me Marlon.

In Riley’s own words, the film offers us “a psychoanalysis of Marlon Brando by Marlon Brando himself.” This effacement of the director’s role in collecting and editing Brando’s recordings is telling and characteristic of the film’s own conceit of authenticity. Director and audience alike are mere spectators to what is ostensibly a deeply personal self-examination, one equally at home in Freud’s divan or Stanislavski’s rehearsal space. Riley uses Brando’s own living room as the central space where the actor’s disembodied voice reminisces, calling forth his affective memories to exorcise them. The purpose of these recordings remains an intentional mystery throughout, and one has to admit it adds an aura of premonition to the proceedings, as if Brando always knew that the tapes would be dredged up and put on display.

Indeed, in an uncanny sound-bite, Brando presages Riley’s project, imagining his self-mythology remade in documentary form: “It’ll be a highly personalized documentary on the life activities of myself, Marlon Brando.” Immediately following this quote (though the change in tone and recording quality suggests a contrived continuity), Brando imagines what we might learn about him from such a project:

We establish that he’s a troubled man, alone beset with memories in a state of confusion and sadness, isolation, disorder. He’s wounded beyond being able to be social in an ordinary way he becomes like a mechanical doll. Maybe he felt like that he was treated badly and he’s angry about the treatment. He’s collected bit of information here. Odd bits of film to try to explain “Why are you this way?”

The documentary’s narrative suggests that he’s talking about himself, but he could just as easily be talking about any one of his roles. Such blurred distinctions highlight precisely what’s at the core of the Method, where actors are encouraged to lose themselves in their roles. Even the imperative embedded in the title of the film — Listen to Me Marlon, evidently a quote from Adler — seems like self-direction, the actor’s call to himself. Brando’s monologue is like a self-prescribed talking cure that hopes to plumb the depths of his past to make sense of his present, a process that echoes another of Adler’s sound-bites from the film: “Do not bring anything in the present that doesn’t have the past.”

Riley’s decision to cede over all diegetic control to Brando’s voice, creating a holistic image of the actor from recordings and interviews that span decades, reinforces the very tenets of psychoanalysis and Method acting. The film’s most laudable accomplishment may very well be the way it reminds us how influential these complementary schools of thought have been in thinking about performance and identity in the intervening decades. Brando’s recordings are obsessed with the following question: “Why is it that we behave the way we do?” Looking inward and following the imperative of his twinned interests in psychoanalysis and Method acting, it’s no surprise that Brando (and Riley) don’t come up with a satisfactory answer.

Instead, Listen to Me Marlon works best as a performance of Method acting. It’s a representation of authenticity that exposes its own construction in hopes of appearing and thus being more truthful. In that, it is as pure a portrait of Brando as we’re ever bound to get.

¤

LARB Contributor

Manuel Betancourt is a freelance writer based out of New York. He earned his PhD delving into the history and cultural significance of queer fandom. He’s a pop culture enthusiast interested in media representation. You can follow his musings at @bmanuel and his work over at mbetancourt.com.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Acting and Impersonation

Leo Braudy on Acting Otherness and the Academy Awards.

Heroism in the Age of Guerilla Warfare

Grant Wiedenfeld and Masha Shpolberg on David Ayer’s war drama “Fury.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!