Life in the Present Tense: “Like” by A. E. Stallings

Rowland Bagnall considers “Like” by A. E. Stallings.

By Rowland BagnallNovember 25, 2018

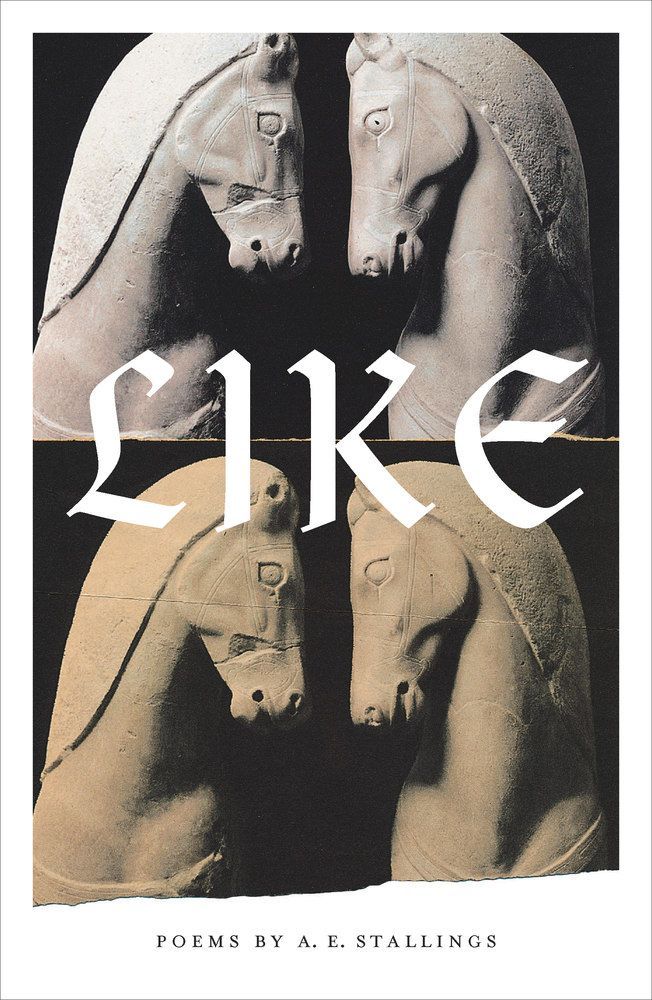

Like by A. E. Stallings. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 160 pages.

IN THE SEPTEMBER 2012 issue of Poetry magazine, the poet and classicist A. E. Stallings reflected on living in Athens, where she moved with her husband in 1999. “The one thing people will ask you here,” she writes, “if you are, as I am, clearly a foreigner, is: Are you here permanently? Are you planning to go back?” Nearly 20 years after her move, Stallings continues to live and work in Greece, where the immediacy of contemporary Athens collides with ongoing meditations on motherhood, mythology, politics, and poetry. In Like, her latest collection from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Stallings presents a diverse quiver of poems — arranged in alphabetical order — polished and sharpened by her typically innovative use of traditional verse forms, poised vocabulary, and a playful dexterous teasing-out of simile and metaphor.

While the alphabetical arrangement of the collection creates a kind of echoing, it also reveals Stallings’s distinct threads and themes. Prominent among them is her interest in writing about all-encompassing, everyday parenting. Recalling what the inside-cover calls Stallings’s “archaeology of the domestic,” which grows and changes with her children, as in “Ultrasound,” from Hapax (2006), these poems continue in the spirit of her previous collection Olives (2012), written “smack in the middle of life, marriage and kids,” as she says to one interviewer, “and [which] I hope is full in the way that my life is currently very full.”

Certain poems in Like exist as an extended meditation on the objects of domestic routine — a pair of scissors, a cast iron skillet, a wooden children’s toy, “[n]odding its wooden head” to the mechanical horse-and-dancer of Elizabeth Bishop’s “Cirque d’Hiver.” Don’t miss the “genuine horsehair,” either, rounding out “The Last Carousel,” which showcases the poet’s wit and metaphorical precision. The iron skillet, accidentally cleansed of its “black and lustrous skin” becomes “vulnerable and porous / As a hero stripped of his arms,” while her poem about pencils scratches steadily toward a blunt and darkly comic close, surrendering itself to Time, that “other implement / That sharpens and grows shorter.”

Elsewhere, Stallings plays the role of archivist, recording the minutiae of urban Athens — a city of “folding chairs” and “broken windowpane[s],” “ill-made potholed modern road[s]” and the occasional whiff of tear gas lingering behind after a protest — alongside snapshots of domestic life: pruning the garden, delousing her daughter (“How pediculous!”), searching on her hands and knees for “[s]ome vital Lego brick or puzzle piece.” Not least due to her standing as a classicist and translator, it struck me how related Stallings’s Greece feels to the world of Homer’s Odyssey. The supernatural notwithstanding, the setting of Homer’s epic “feels entirely realistic, even mundane,” writes Emily Wilson in the introduction to her new translation, “a world where a mother packs a wholesome lunch of bread and cheese for her daughter, where there is a particular joy in taking a hot bath, where men listen to music and play checkers, and lively, pretty girls have fun playing ball games together.”

Where Stallings writes specifically about her children, she joins a formidable group of contemporary poets (on my side of the Atlantic, at least) engaged in exploring the same fullness of life she attributes to her time in Athens. Stallings’s poems chime with recent work by Fiona Benson, Liz Berry (whose poem “The Republic of Motherhood” was recently awarded the Forward Prize for Best Single Poem), and Sinéad Morrissey, especially the title poem of her 2017 collection, On Balance, which rebuts the wished-for ordinariness of Larkin’s “Born Yesterday,” written for the infant Sally Amis. What Stallings’s poetry shares with these writers might be something like awareness, a quality of self-reflection that accompanies the world renewed by parenthood. Anne Stevenson seems to touch upon this in the final stanza of her “Poem for a Daughter.” “A woman’s life is her own,” she writes, “until it is taken away / by a first, particular cry”:

Then she is not alone

but part of the premises

of everything there is:

a time, a tribe, a war.

When we belong to the world

we become what we are.

I think it’s this feeling “part of the premises / of everything there is,” that governs much of Stallings’s poetry, including “Lost and Found,” the longest poem in the new collection, a kind of Chaucerian dream-vision in which the poet, following an argument with her son, is guided through a cratered moonscape by Mnemosyne, the classical goddess of memory, to the place “[w]here everything misplaced on earth accrues, / And here all things are gathered that you lose.” It isn’t only objects that end up here but an entire imaginative spectrum of the irretrievable, from the rooms to which we can’t return and the insomniac’s lost hours of sleep, to “the letters / We meant to write and didn’t” and “the frayed, lost threads / Of conversations […] we’d thought we’d spun / Only to find they’d somehow come undone.” On waking, the world is business as usual: hurried school-runs, packed lunches, paperwork, and bills. And yet, the poet resolves “[t]o live in the sublunary, the swift, / Deep present.” Stallings attends to the moment and the momentary, even as they pass to “[t]he light on my children’s hair, my face in the glass / Neither old nor young; but bare, intelligent.”

Thinking about Stallings as a poet who writes so unapologetically about her life as a parent, I’m reminded of an article by Ange Mlinko, published in the September issue of Poetry back in 2009. In it, Mlinko expresses her suspicion toward what she refers to as “mommy poems,” suggesting them to be, on the one hand, “intense, but also kind of boring” and on the other a frustrating instance of the commodification of contemporary poetry, and of motherhood in general. I found myself wondering what Mlinko might have to say about Stallings’s poems, especially given that Mlinko is thanked in the acknowledgments. In the case of Like, I expect she would approve. “I don’t want to read anthologies of mother poems,” she writes, though “I am always interested in what individual poets write about their children, in context with all the other things they write about.”

As an academic, an expatriate, and a North American mother of two, Stallings is careful to balance her experience of motherhood with the realities of the European refugee crisis, in which Greece plays a significant and complicated role. “I’m grateful tonight / Our listing bed isn’t a raft,” begins one poem, “Precariously adrift / As we dodge the coast guard light,” “That we didn’t buy cheap life jackets,” that “we don’t scan the sky for a mark, // Any mark, that demarcates a shore / As the dinghy starts taking on water.” Later on, the sequence “Refugee Fugue” stands out as one of the collection’s most successful moments, the poem transfiguring itself through different forms and voices like Shakespeare’s Ariel, who’s singing echoes softly through the poem:

A fathom deep, the body lies, beyond all help and harms,

Unfathomable, unfathomable, the news repeats, like charms,

Forgetting that “to fathom” is to hold within your arms.

The sequence ends with a found poem of “Useful Phrases in Arabic, Farsi/Dari, and Greek,” constructed from a “Guide to Volunteering” distributed in Athens in March 2016. Somewhere near the middle, the poem introduces its anonymous dramatis personae — “Refugee / Volunteer / Foreigner / Friend” — though we are left to write the conversations that exist between the gaps ourselves:

I don’t understand

I don’t speak Arabic / Farsi

Slowly

Come here

You’re safe

Are you wet / cold?

[…]

How many people?

Sorry

Stay calm

One line, please

Next person

The poem reminds me of certain passages from Human Flow (2017), Ai Weiwei’s massive documentary exploring the extent of the global refugee crisis, and his recent installation Law of the Journey (2017), on display last year at the Trade Fair Palace in Prague, a 230-foot-long black life raft, suspended from the ceiling, crowded by 258 inflatable faceless figures.

Like Ai Weiwei, Stallings seems to understand the inherent connection between displacement and anonymity. It’s an idea that surfaces several times in the collection, as in “Alice, Bewildered,” taking an episode from Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass as its starting point, in which Alice wanders into “the wood where things escape their names.” On entering this new environment, Alice temporarily loses grasp of her identity, suddenly “un-twinned from the likeness in the glass.” The scene in Carroll’s novel is short: Alice briefly forgets her name — and the names of everything surrounding her — but remembers who she is on exiting the wood. In Stallings’s poem, she never recovers, the poem ending before she has time to “reclaim / The syllables that meant herself,” disintegrating into babble, half riddle, half tongue-twister:

Yet in the dark ellipsis she can tell,

She’s certain, that her name begins with “L” –

Liza, Lacie? Alias, alas,

A lass alike alone and at a loss.

Alice’s displacement here is permanent or, at the very least, indefinite, returning us to the question posed to Stallings, time and again, during her time in Greece: “Are you here permanently? Are you planning to go back?”

Toward the end of that article in Poetry magazine, Stallings refers to a Greek proverb which, for her, articulates the uncertainty of her status as a full-time resident in Greece: “[N]othing is more permanent than the temporary.” The proverb returns in the collection’s opening poem, a villanelle concerning her family’s indefinite period abroad: “Just for a couple of years, we said, a dozen years back.” Here, it acts as a kind of refrain, but the proverb reaches out across the rest of the collection, too, coloring the other poems, which so often turn to a consideration of the temporary and the permanent. It’s understandable how this might come to be the overwhelming preoccupation of the classicist; it’s certainly a steady presence in the work of Alice Oswald (“Dunt: a poem for a dried up river” springs to mind). What’s clear in Like, however, is the way Stallings embraces the inevitable falling-away of things — of language, cities, people, civilizations — not as a way of reevaluating the past, but as a means of focusing on the fullness of life in the present tense, on the stuff that’s here now but might not be for long.

As for the poet, the act of writing comes to serve as a kind of solidification, a way of preserving the present before it slips away entirely. “I felt the moment pass / Right through me,” writes Stallings in the final stanza of “Lost and Found”:

currency as it was spent,

That bright, loose change, like falling leaves, that mass

Of decadent gold leaf, now turning brown –

I could not keep it; I could write it down.

¤

LARB Contributor

Rowland Bagnall is a writer and poet based in Oxford, United Kingdom. His second collection, Near-Life Experience, was published by Carcanet Press in 2024. A selection of his poems, essays, and reviews is available at his website.

LARB Staff Recommendations

When a Love Poet Writes an Epic: Catullus’s “Poem 64”

Daisy Dunn revisits Catullus’s “Poem 64.”

Homer for Scalawags: Emily Wilson’s “Odyssey”

Richard H. Armstrong journeys through Emily Wilson’s new translation of Homer’s “Odyssey.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!