The Legacy of Eric Garner: Policing Still Going Wrong

The killing of Eric Garner gets a nuanced treatment from one of the left’s most polarizing stylists.

By Shehryar FazliDecember 11, 2017

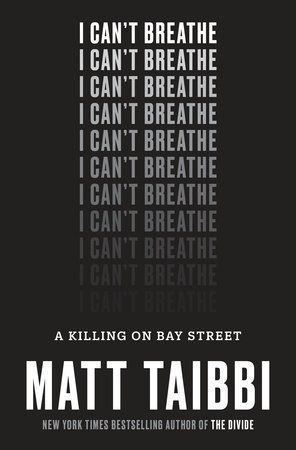

I Can’t Breathe by Matt Taibbi. Spiegel & Grau. 336 pages.

A REPUBLIC, if you can keep it. So said Benjamin Franklin when asked in 1787 what form of government the United States was getting. But what kind of republic? Many would want to believe that it’s one that improves with time, and in critical ways the United States has, given its origins in Indian mass murder and black slavery. But the weight of malign history presses down on communities of color, and on July 17, 2014, it squeezed the plea, “I can’t breathe,” from a dying black man in Staten Island.

Eric Garner’s declaration, before NYPD officer Daniel Pantaleo’s chokehold took his last breath, gives Rolling Stone correspondent Matt Taibbi the title of his latest book, an exploration not just of Garner’s experience but also that of many black men and women trapped in a still-stifling American republic.

It’s worth starting with a few words about the recent controversy around Taibbi, related to a 2000 memoir, The eXile: Sex, Drugs, and Libel in the New Russia, he co-wrote with Mark Ames about their time editing an alt-weekly in Moscow during the 1990s. In one chapter, Ames described sexual harassment of female colleagues, which in the wake of the Weinstein affair has provoked fresh debate about Taibbi’s past conduct. In a late October Facebook post, after he faced questions about this while promoting the current book, Taibbi acknowledged that the behavior described in The eXile was “reprehensible” but also fictional, and denied having made “advances or sexually suggestive comments to any co-worker in any office, here or in Russia.” He said the memoir “was conceived as a giant satire” about Americans in post-Soviet Russia: “In my younger mind this sounded like a good idea, a cross of Andrew Dice Clay, The Ugly American and Charlie Hebdo. But in practice it was often stupid, cruel, gratuitous and mean-spirited.” To my knowledge, no one has accused either Taibbi or Ames of harassment.

Taibbi’s career since The eXile has not been without controversy — a satirical 2005 New York Press essay titled “The 52 Funniest Things About the Upcoming Death of the Pope” led to his editor being fired — but in the process he’s also become the angry and eloquent writer these times need. His penchant for burlesque, like that of his Rolling Stone predecessor Hunter S. Thompson, is grounded in contempt at ruling classes and structures. Like Thompson, he can turn this contempt into powerful and elegant prose. His July 2009 essay, “The Great American Bubble Machine,” in which he memorably described Goldman Sachs as “a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money,” expanded our vocabulary for the Great Recession. He has confrontational words for his foes, such as in his description of the “asshole chief of Merrill Lynch who bought an $87,000 area rug for his office while his company was imploding.” Clinton’s Treasury Secretary Bob Rubin was “the prototypical Goldman banker. He was probably born in a $4,000 suit, he had a face that seemed permanently frozen just short of an apology for being so much smarter than you, and he exuded a Spock-like, emotion-neutral exterior; the only human feeling you could imagine him experiencing was a nightmare about being forced to fly coach.”

Taibbi’s generally been more reflective in his books, but without conceding any of his rage. In his 2014 book, The Divide: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap, he describes Russia in “the waning days of the Soviet empire” as a “dysfunctional wreck of a lunatic country” with “two sets of laws, one written and one unwritten. The written laws were meaningless, unless you violated one of the unwritten laws, at which point they became all-important.” Writing about inequality in the United States, he says, “We have a profound hatred of the weak and the poor, and a corresponding groveling terror before the rich and successful, and we’re building a bureaucracy to match those feelings.”

In light of all this, what may surprise his readers about the new book is its moderate tone — all the more so given the polarizing subject matter.

In I Can’t Breathe, Taibbi titles almost all of his chapters after an individual whose experience prompts a wider discussion about the Garner story and the black experience with the American justice system. There’s Ibrahim Annan, who tells police knocking on his car window in Staten Island to “get a fucking warrant,” and is met with shattered glass and 20 blows to his face and head. There’s Carmen Perez, an activist leading the Justice League NYC that was prominent among the huge crowds filling the streets in December 2014, after the district attorney announced that Pantaleo wouldn’t be indicted. There’s Pedro Serrano, a Puerto Rican who grew up on the streets of the North Bronx, avoiding the sections where nonwhites weren’t welcome, and who eventually joins the NYPD. During the policing revolution of the 1990s, he has to adopt aggressive practices against his instincts. There’s Erica Garner, Eric’s daughter, who campaigns for justice after his death. Throughout, Taibbi writes evocative scenes of police subjecting young black men to physical, sexual, and psychological humiliation. By curbing his customary Rolling Stone chutzpah, he gives these characters and events room to reveal their drama and get the reader’s blood hot on their own.

The center of gravity, of course, is Garner himself, who was one of those irrepressible personalities, with a matching physique, who attract special attention. He sold tax-free cigarettes: it’s worth emphasizing that point. Although he’d dealt drugs in the past, he was now bootlegging a legal substance, enabled by Michael Bloomberg’s short-sighted policy to impose the country’s highest cigarette taxes on New York, raising the retail price by six bucks a pack. This was a gift to smugglers:

Virginia and other low-tax states of the South began flooding New York with cheap smokes brought in by canny street arbitrageurs, who undercut New York’s tax laws one illicit trunkful at a time. Eric Garner became one of those smugglers. He had several employees and regularly sent mules on runs to Virginia, where they filled their trunks with wholesaled cartons.

Taibbi’s build-up of events gives substance to the impression that the most casual listener has hearing Garner, in the YouTube clip of his killing, telling the cops to leave him alone: this man is at a breaking point. It’s in his voice, its pitch, its despondency. Just leave me alone. He’d been stopped so many times and sent to jail so many times for the smallest things that his very presence seemed to be considered criminal. In this instance, all he’d done was break up a fight nearby. Leave me alone. In the same way one watches the Zapruder film and urges Kennedy to duck, one watches the Garner clip pleading with the cops to just let the man be.

¤

An amiable cigarette dealer drawing so much police attention was a by-product of the most touted, intellectually appealing, and disastrous-in-practice policing strategies: Broken Windows.

The story begins in the late 1960s, and with Richard Nixon, who made his the party of law and order, sights set on exploiting “Middle American” anxieties about urban unrest, forced integration, and anti-war protests. By the time he assumed office, the Supreme Court’s 1968 Terry v. Ohio decision had already empowered the police to bring about order by ruling that the Fourth Amendment prohibition on unreasonable searches and seizures didn’t apply to police stopping and frisking without probable cause, if the police had a reasonable suspicion that the person has committed or is about to commit a crime. Nor did it apply to someone who may be armed and dangerous. As Taibbi argues, “[t]he Terry decision essentially said that the legal standard for a whole generation of field searches would henceforth rest in the minds of police officers.”

In an influential March 1982 Atlantic essay entitled “Broken Windows,” George L. Kelling (on whom one of Taibbi’s chapters is based) and James Q. Wilson stressed the average resident’s “fear of being bothered by disorderly people. Not violent people, nor, necessarily, criminals, but disreputable or obstreperous or unpredictable people: panhandlers, drunks, addicts, rowdy teenagers, prostitutes, loiterers, the mentally disturbed.” The objective should be, they argued, “order maintenance.” Broken windows on buildings and graffiti on subway trains signified disorder, and disorder inspired fear, and if Joe Q. Public was afraid, he was a victim.

This idea has enormous appeal, but “order” is a dicey objective. Vague wording like this — not necessarily criminals — lends itself to the tyranny of the majority, and that’s precisely what happened with the black community in New York and elsewhere in the equally vague War on Drugs. The fear of disorder was racially coded. Taibbi cuts to this with his characteristic economy: “New Yorkers who are afraid of crime are already victims. Many New Yorkers are scared of black people. Therefore, being black is a crime.”

For Pedro Serrano, later to join the police, “the new regime just put an official government stamp on neighborhood rules that he’d understood since his earliest childhood days. The streets may seem free and public, but they don’t belong to you. You walk down them at someone else’s pleasure, with someone else’s permission.” Taibbi adds, “In order to justify all of these stops, police had to be trained to see the young men they were tossing as deserving what they got, before they even did anything.” The stops often turn violent if these young men offer the mildest resistance, and in such cases the system favors the officers over civilians:

A black man with a shattered leg has a virtually automatic argument for certain kinds of federal civil rights lawsuits. But those suits are harder to win when the arrest results in a conviction. So when police beat someone badly enough, the city’s first line of defense is often to go on offense and file a long list of charges, hoping one will stick. Civil lawyers meanwhile will often try to wait until the criminal charges are beaten before they file suit […] If the beating is on the severe side, the victim has the power to take the city for a decent sum of money. But that’s just money, and it comes out of the taxpayer’s pocket. The state, meanwhile, has the power to make losses in this particular poker game very personal. It can put the loser in jail and on the way there can take up years of his or her life in court appearances.

A mini library of recent scholarship on race and justice in the United States has linked pre-1960s segregation to the War on Drugs to the tough-on-crime ’90s to the killings of black men in the last few years. As such, the first part of this book, culminating in Garner’s killing, offers little that’s new. It’s in Part Two that Taibbi moves into less visited places, in particular the Escher-like police accountability maze “where citizen complaints go to die.” This is where he’s back on his habitually strong ground, showing us the gloomy insides of what Hunter S. Thompson would have referred to as the System.

The Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB), he tells us, is the most common recipient of police abuse complaints. An independent civilian agency, it conducts an investigation based on information from the aggrieved citizen and then makes a presentation to a three-member CCRB panel, which makes one of six recommendations. The most relevant of these is “substantiated,” which prompts, typically, a reference to the Administrative Prosecution Unit, an executive rather than a judicial body comprising prosecutors, defenders, and judges who are on the police department’s payroll. An APU finding of guilt can lead to punishments of various grades of severity, from a talking-to (“instruction”) to dismissal. But the police commissioner can override any ruling, and often does. It’s a rigged and opaque system.

The story of Eric Garner is not just a story of the chokehold but also, as in many police brutality cases involving race, of the failure to hold the officer accountable. It is also, finally, a story about the public response to the grand jury’s decision not to indict Pantaleo. But the huge protests and unrest provoked by this as well as a grand jury’s similar decision in the Michael Brown shooting in Ferguson, has been widely documented and seen: the growth of the Black Lives Matter movement, black celebrities embracing the mantra, I can’t breathe, the counter-protests by police and public officials pleading the “blue” lives matter, too. Less known is the despairing quest by Garner’s family and activists to obtain and publicize information about his case.

The grand jury process seemed like a swindle from the start. District Attorney Dan Donovan introduced a large amount of material and witness accounts from Pantaleo’s police colleagues that mitigated the case against him, rather than focusing on inculpatory evidence. Because grand jury minutes are usually sealed from the public, the Garner team had to prove to a judge that the case stank enough to justify unsealing. After this failed, the Garner family tried to obtain Pantaleo’s CCRB file, specifically how many complaints against him the CCRB had substantiated. In the CCRB jungle, this mission, too, ended with failure: “Years of pitched legal battle over a single number. Even the release of that much information was too much for the city to bear.” Meanwhile Dan Donovan, who failed to prosecute Pantaleo, won a special election in May 2015 to serve New York’s 11th district in Congress.

Taibbi’s book is in part a well-reported account of Garner’s life and death and a useful history of Broken Windows policing and its impact. At its best, however, it’s a procedural drama with a deadly serious subject and without a redemptive finale. It’s another worthy Taibbi chronicle of a dehumanizing bureaucracy that serves and protects its own.

¤

It seems unthinkable that a major politician today could say something like “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever” and still be a credible contender for a party’s presidential nomination. Donald Trump has never quite said that, but his appeals to white supremacists before and after the election would have George Wallace’s blessing. If the United States is, as Taibbi says, “a country frozen in time for more than fifty years, stopped one crucial step short of reconciliation and determined to stay there,” then there are several questions to consider: What’s needed to take that final step? And what happens otherwise? How much more stress can this society take?

The Justice Leaguers and Erica Garner’s struggles for more robust action in police brutality cases continue, even as public attention has waned. Taibbi offers a valuable critique of Black Lives Matter and other contemporary protest movements, differentiating them from the Civil Rights movement of the ’60s. The latter focused on “economic strikes and nonparticipation campaigns to apply pressure on people in power,” the former on the dissemination of images through social media, which while spreading the message ultimately doesn’t hurt those in office. Recent protest movements have dissipated without lasting results. By focusing on police brutality, they may miss the bigger crisis of a ruthlessly punitive criminal justice system. It’s tanked-up on executions, mass incarceration, solitary confinement, mandatory minimums.

For a majority with limited interaction with the police, this side of the American state is completely, and comfortably, foreign. And so it acquiesces in the state’s accretion of retributive authority and invites the question: what kind of republic?

¤

1. A recent article in Paste, by Walker Bragman, “trace[s] the effort to cast eXile as a factual memoir back to an alt-right author named Jim Goad in 2011.”↩

¤

LARB Contributor

Shehryar Fazli is an author, political analyst, and essayist who divides his time between Pakistan and Canada. He is the author of the novel Invitation (2011), which was the runner-up for the 2011 Edinburgh International Festival’s first book award. He can be reached via email at [email protected].

LARB Staff Recommendations

Elegy for a Cousin

Cinque Henderson on Danielle Allen’s memoir “Cuz: The Life and Times of Michael A.”

The Revolutionary Force of Stupidity: A Conversation with Matt Taibbi

Gregg LaGambina talks to Matt Taibbi about his new book, "Insane Clown President."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!