“Learn the Use of Explosives!”: On Jacqueline Jones’s “Goddess of Anarchy: The Life and Times of Lucy Parsons, American Radical”

Elaine Elinson praises “Goddess of Anarchy: The Life and Times of Lucy Parsons, American Radical” by Jacqueline Jones.

By Elaine ElinsonMarch 20, 2018

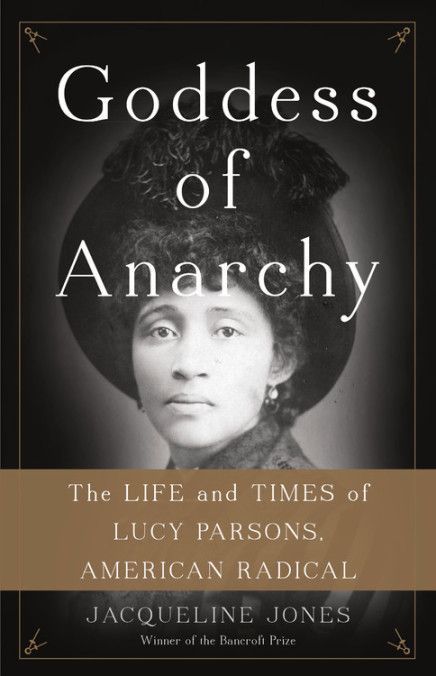

Goddess of Anarchy by Jacqueline Jones. Basic Books. 480 pages.

THE BOMB THAT TORE through Chicago’s Haymarket Square rally in 1886 left an indelible mark on the history of US left politics. The police raid on the meeting that demanded an eight-hour day, the explosion that killed seven police officers and up to eight civilians, the convictions of the anarchist organizers, and their executions shaped a whole generation. Emma Goldman called it “the most decisive influence in my existence.” Socialist Eugene Debs decried the executions and the “sordid” capitalists who “pounced upon these men with the cruel malignity of fiends and strangled them to death.” Even Mexican revolutionary Enrique Flores Magón remembered learning about the hanging of “our comrades Parsons, Fischer, Engel and Spies” as a young boy.

Yet one of the key players in those events — Lucy Parsons — is often left out of the story. Renowned during her lifetime, her legacy has been marginalized, her powerful voice rarely heard.

In her new biography, Goddess of Anarchy: The Life and Times of Lucy Parsons, American Radical, Bancroft Prize–winning historian Jacqueline Jones tries to set the record straight. Scouring hundreds of newspapers, left-wing journals, and labor archives from all over the country, Jones has pieced together the story of this bold labor organizer, prolific writer, and impassioned orator.

But what Jones finds will surprise many.

For although Lucy Parsons was very much in the public eye during the late 1800s and the early 1900s, she was not always what she seemed to be.

Jones has done a marvelous job of excavating Parsons’s often contradictory and long-obfuscated history, revealing many new facts even though we may never understand the underlying “whys.”

Perhaps the most surprising discovery is that Lucy Parsons was not born in Texas to Mexican and Native American parents as she claimed. She was an African American, born into slavery in Virginia in 1851. Her putative owner, a Confederate Army surgeon named Tolliver, took all his slaves — including Lucy and her mother Charlotte — to Waco, Texas, in 1863 in the midst of the Civil War.

This arduous journey must have had a tremendous impact on the teenage Lucy, but little is known about it. Jones picks up the record in Texas after the war. During the brief postwar political moment when blacks and whites could marry in that state, Lucy wed Albert Parsons, a Confederate Army veteran. The young couple moved to Chicago, where Lucy reinvented herself, with Albert’s support.

Albert worked as a printer and Lucy, an excellent seamstress, set up a small dressmaking business. But there was great labor unrest and soon they both become involved in union organizing and the nascent socialist movement. Albert became the editor of The Alarm, an anarchist paper that shared a building with other radical newspapers, including the Arbeiter-Zeitung. There they met many German anarchists, including those who would become Albert’s fellow defendants in the Haymarket trial.

Lucy and Albert started the Social Democratic Party, later the Workingmen’s Party of the United States (WPUS), advocating against the rampant oppressive working conditions and focusing on the white working class. Lucy describes the massive railroad strike of 1877 as a “turning point” for them, one that showed “the potential of the masses.” They both extolled the use of violence to overthrow capitalism. Albert wrote in The Alarm, “Gunpowder brought the world some liberty and dynamite will bring the world much more as it is stronger than gunpowder. […] Dynamite will produce equality.”

Lucy’s seminal article, “To Tramps: The Unemployed, the Disinherited, and Miserable,” called on the “legions of famished men, trudging through the streets of windswept Chicago” to “learn the use of explosives!” This article, Jones asserts, “set her and Albert on a path to a fatal reckoning.” And it certainly drew the attention of factory owners and law enforcement, who regularly surveilled and harassed the anarchist couple.

When Albert was arrested with seven others for allegedly bombing the Haymarket rally (although he and Lucy were blocks away in a tavern at the time), Lucy led their defense campaign, traversing the country, drumming up support in several dozen cities, from New York to Detroit to Omaha.

Though the police hounded her everywhere she went, she was not deterred by their threats, gag orders, and arrests. In fact, Jones, asserts, she took delight in the chase. Barred from a hall, she would exhort a crowd from the sidewalk, her fervent admonitions met with exuberant cheers.

In Columbus, Ohio, this defiance landed her in jail. Always cognizant of the publicity value of her ill treatment at the hands of law enforcement, she wired Albert: “Arrested to prevent my speaking. Am all right. Notify press. Lucy.”

The newspapers became fascinated with her. Reporters described her rhetoric in terms that evoked the Great Chicago Fire: “incendiary,” “inflammatory,” and “red hot.”

The journalists who packed her speeches were also intrigued by her appearance, noting her elegance in dress, her tall bearing, and beautiful features. They were mystified by her ethnic background, calling her a “dusky representative of Anarchy,” a “sanguinary Amazon,” and the “quadroon anarchist of Chicago.” Parsons used their befuddlement to her advantage, often mounting the stage in a stylish hat and a fashionable dress she had sewn herself, then announcing to the crowd “I am an anarchist,” and launching into a militant tirade.

As a teenager, Lucy had attended the “colored school” in Texas and developed a lifelong love of reading; her homes were always filled with books. She became a prolific writer, editing two radical journals, Freedom: A Revolutionary Anarchist-Communist Monthly and the Liberator, and writing articles for dozens more. She also wrote a book, The Life of Albert R. Parsons, With Brief History of the Labor Movement in America, which she sold at every opportunity. At times, it was her only source of income.

After the Haymarket executions, she kept up a grueling schedule, agitating for workers rights and participating in many left-wing formations. For decades she traveled the country, supporting strikes and seeking justice for Tom Mooney, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, and other workers she felt were victims of trumped-up charges as the Haymarket martyrs had been. Jones writes that she “also kept selling her pamphlets and books, which she carried around in tattered shopping bags.”

Attracted to the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, better known as the Wobblies) for their commitment both to labor and to free speech, Lucy joined them on many street-corner organizing campaigns. She was by then accustomed to the police hounding (and sometimes jailing) her at every rally. After being barred from speaking in a hall in Chicago, she taunted the police on the sidewalk: “O, men of America, degenerate Yankees, is this your boasted liberty? Is this your free speech? Is this your right to assemble? O, the glorious stars and stripes!”

Parsons joined the International Labor Defense, founded in 1925 by Chicago communists, to provide lawyers and generate public outrage in support of jailed leftists. She sat on the executive board with very distinguished company: Upton Sinclair, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, and Clarence Darrow.

But both her public and private life were rife with conflict. Her first political quarrels were with mainstream labor unions, which she criticized for merely seeking “betterment and respectability” rather than the overthrow of the capitalist system.

She also estranged some of her left-wing comrades. Wary of her calls for the “heads of capitalists impaled on spikes” and warnings that “rivers of blood will have to run,” and perhaps jealous of her popularity, they accused her of trying to hijack meetings and barred her from speaking. Undaunted, she would take a seat in the back of the hall, then march to the stage and deliver her own speech, most often to wild applause from the crowd.

Her most public feud was with Emma Goldman, whom Jones calls “her chief rival for publicity and resources.” The disagreement started with Lucy’s harsh critique of Goldman’s public advocacy for free love (even though Parsons took many lovers after Albert’s execution) and Goldman’s accusation that Parsons was a “hypocrite” whose “fame depended wholly on her widow-martyrdom rather than on any original contributions” to anarchism.

But Lucy’s estrangement from her son Alfred Jr. is perhaps the most heartbreaking. While Lucy was campaigning against the US war in the Philippines, Alfred Jr. announced he was joining the Army. After a physical confrontation, she had him committed to the Elgin Asylum, a psychiatric hospital, where he was locked away for 20 years. Albert was abused by guards and other patients, at times because of his mother’s notoriety. He died there. Although Lucy kept his ashes on her mantle, Jones could find no record that she ever visited him in the asylum.

As a longtime admirer of Lucy Parsons, I found it difficult to read some of these bitter truths. I am sure it was even more difficult for Jones to write about them. The author’s rich narrative, based on meticulous scholarship and wide-ranging research, provides a much more complex picture of Parsons than has ever previously been presented.

Jones, who holds the Ellen C. Temple chair in Women’s History at the University of Texas at Austin, is particularly adept at setting the historical framework for each period of Parsons’s life — from slavery through the Gilded Age and the Palmer Raids all the way up to the dawn of World War II — through the lens of the progressive movement. At times the narrative slows due to detail. There are so many feuds and spats, friendships and fallings-out among the left, that it is sometimes hard to see the forest for the trees. Lucy and her comrades joined so many different left organizations — anarchist, anarcho-syndicalist, socialist, communist — that a guide to each group’s political ideology would have been helpful.

This close examination of Lucy Parsons’s life raises many questions. Why did she hide her childhood in slavery and her African-American heritage? Why did she focus her organizing on the white working class, even after the Great Migration brought tens of thousands of Southern blacks to Chicago? Jones addresses these contradictions, and provides answers when she can. But she adds, “Parsons was her own person, and try as they might, no one could affix predictable labels to her or define her background with any precision […] she always seemed quite unlike any woman they had ever encountered.”

Jones depicts Lucy Parsons as an audacious, iconoclastic woman, defying all conventions to fight for workers’ rights. That’s no doubt how she would like to be remembered.

¤

LARB Contributor

Elaine Elinson is the former editor of the ACLU News and the co-author of Wherever There’s a Fight: How Runaway Slaves, Suffragists, Immigrants, Strikers, and Poets Shaped Liberties in California (2009), winner of a gold medal in the California Book Awards.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Period Piece of the Present

Bruce Robbins on Raoul Peck's "The Young Karl Marx" and how it relates to the Global South.

Is Socialism Still a Dirty Word?

Tyler Zimmer on Verso's "The ABCs of Socialism."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!