The Latin Epigram: Brevity, Levity, and Grief

Art Beck meditates on the nature of the Latin epigram and offers his translations of Martial.

… Miramur, tantum capiant qui membra furorem.

Cum sit forma levis, clamor et ira gravis.

… I wonder how your limbs can contain so much fury.

Such a silly little form, bellowing with the weight of its rage.

— from Pygmy, Luxorius, circa 525 CE

Ad mortem sic vita fluit, velut ad mare flumen.

Vivere nam res est dulcis, amara mori.

Life flows into death the way rivers seek the sea.

Sweet water rushing to an undrinkable ocean.

— John Owen (1564–1622)

¤

I. The Undefinable Exemplified

UNLIKE THE SONNET or other “received” forms that can be defined as various patterns of lines, rhyme schemes, meters, et cetera, the epigram is somewhat slipperier. It’s normally “described” rather than “defined.” The Academy of American Poets site seems to make as good an attempt as any:

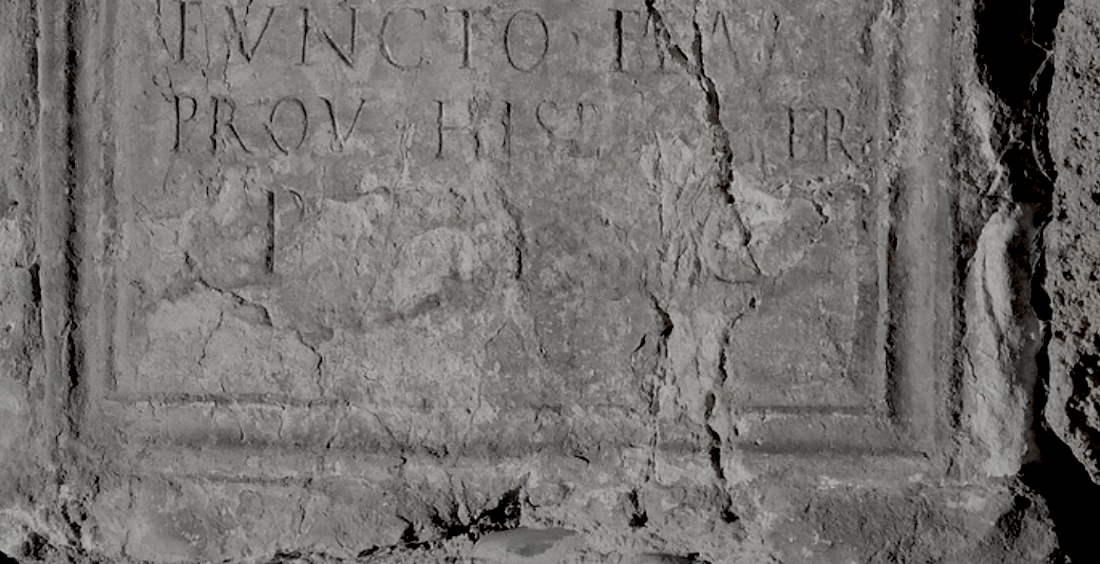

An epigram is a short, pithy saying, usually in verse, often with a quick, satirical twist at the end. The subject is usually a single thought or event. The word “epigram” comes from the Greek epigraphein, meaning “to write on, inscribe,” and originally referred to the inscriptions written on stone monuments in ancient Greece.

They expand by quoting Coleridge:

What is an Epigram? A dwarfish, whole.

Its body brevity, and wit its soul.

What Coleridge and the Academy say about the epigram might also be characterized as an authorial attitude, combined with a poetic self-discipline of not wasting words. Epigrams are often complaints, but they’re never expansive “howls” in the Allen Ginsberg mode. Rather, the epigram’s discipline is a bit akin to the dictum of going through your corporate email kvetches one last time to remove all the adjectives before clicking “Reply All.”

Epigrams can revel in negative or scurrilous utterances, but that’s not a requirement. If anything’s essential, it may be a certain paradoxical irony. And even that’s all the better when it nudges rather than smacks you. Mae West’s quip “To err is human, but it feels divine” is a resonant smile not a zinger. Is it an epigram? I think so, in the sense that it’s a poem whose author was disciplined enough to intuit that every line but the last should be cut.

II. The Monumental Democratized

I’m sure examples of something like the epigram must occur in most every language. English certainly has no shortage. But I’ve spent the last several years translating Martial’s epigrams, and a good bit of time before that translating the North African Roman epigrammist Luxorius, who wrote at the dawn of the so-called dark ages. And it’s the Latin epigram that’s on my mind. In particular, I’m interested in its imputed origins in Greek gravestone etchings, an ancestry I hadn’t thought much about until recently reading a very enjoyable and informative book.

Michael Wolfe is a poet, novelist, essayist, film producer, and classically trained independent scholar. He’s published translations of an extensive array of ancient Greek tombstone epitaphs in a well-received volume titled Cut These Words into My Stone (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013). His selection begins with very early epitaphs, found on gravestones and artifacts as far back as 600 BCE, and then proceeds through the Greek Anthology, where etched epitaph segues into poetic epigram around the late fourth century BCE.

The second epitaph in Wolfe’s sequence is anonymous, undated, and enigmatic.

My name is Dionysius of Tarsus.

I was sixty when I died. I never married.

I wish my father had never married either.

Wolfe wonders:

Were these lines approved by the deceased before his death, or did someone compose them later? A person who knew him? A professional epigrammatist in the pay of a disgruntled neighbor? Spoken in the first-person, the lines sum up a state of mind that readers in any age may recognize.

In my mind, a cautious understatement. I wonder whether Dionysius’ tombstone predated or followed Sophocles famous lines to the effect: never to be born is by far the best, next best to die as early as you can. That sentiment, coming near the climax of the Oedipus trilogy has been translated, adapted, and mulled down through the ages by a panoply of brooding philosophers and poets. Philip Larkin’s “This Be the Verse” could be an expanded gloss on both Sophocles’s pronouncement and Dionysius’ epitaph:

They fuck you up your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

[…]

Man hands on misery to man.

It deepens like a coastal shelf.

Get out as early as you can.

And don’t have any kids yourself.

Dionysius apparently had the worst of that bargain — he lived 60 years, a ripe old age for the time. But unlike Sophocles’s royal protagonist, whose willing death becomes a numinous ritual, he departs as a cynical unwilling everyman. His epitaph, I think, achieves epigram status not only because of its irony and brevity, but also because it starts from an attitude it took Sophocles three long chorus-filled dramas to get to: it complains but doesn’t whine. Dionysius’ humanity is better viewed through Larkin’s jaundiced eye than through that of Sophocles. We weep for Oedipus, we laugh with Dionysius. High tragedy, we sense, is something that someone like our Dionysius can’t afford to indulge. (Of course, Larkin’s poem applies just as well to Oedipus — except that Oedipus’ mum and dad definitely did mean to…)

III. Some Latin Tombstones

Non fui, fui,

non sum, non curo

I wasn’t, I was,

I’m not, I don’t care [1]

This was, by some accounts, one of the most popular Roman Empire gravestone inscriptions, the Epicurean equivalent of “rest in peace.” It also may help serve to illuminate why, in later Christianized Rome, “[u]nder the double weight of religion and empire,” as Michael Wolfe puts it, “the delicate epigram began to buckle. Its defining characteristics — independent vision and a passionate frankness concerning life’s joys and sorrows — gave way to the churchly emphasis on renunciation and salvation.”

Or perhaps put more simply: visions of eternal life tend to suck the dark energy from an art form born at the graveside. The first-century CE Roman poet Martial, whose 1,500-some forays into the metier still represent the holy grail of epigram, uses the gravestone inscription conceit from time to time. In the following two pieces, he first does so with poignancy, then — two poems later in his Book Ten sequence — with his signature “frankness.”

X, 61

Hic festinata requiescit Erotion umbra,

crimine quam fati sexta peremit hiems.

quisquis eris nostri post me regnator agelli,

Manibus exiguis annua iusta dato:

sic lare perpetuo, sic turba sospite solus

flebilis in terra sit lapis iste tua.

Here rests Erotion’s hurried shade, robbed

of life by fate and her sixth winter. Whoever

owns this little plot after me, make an offering

to her small ghost each year. Then, may your

household endure, safe and untroubled.

Let this stone be the only sorrow on your land.

X, 63

Marmora parva quidem sed non cessura, viator,

Mausoli saxis pyramidumque legis.

bis mea Romano spectata est vita Tarento

et nihil extremos perdidit ante rogos:

quinque dedit pueros, totidem mihi Iuno puellas,

cluserunt omnes lumina nostra manus.

contigit et thalami mihi gloria rara fuitque

una pudicitae mentula note meae.

This gravestone you’re reading may be small,

traveler, but cedes nothing to any mausoleum or

pyramid. I attended not one, but two Saecular

Games, sixty-four years apart, and never lost a step

until my dying day. Juno gave me five boys and as

many girls, and every one of their hands

closed my eyes. My marriage was a glory to

behold, and I was faithful to just that one prick.

IV: Praise or Scorn, Paean or Epigram?

Martial, in the still pre-Christian first century, also has an explicitly “afterlife epigram,” but I think it’s best appreciated through a non-believing lens.

XIII, 4 Tus

Serus ut aetheriae Germanicus imperet aulae

utque diu terris da pia tura Iovi.

“Incense”

So that Germanicus may eventually rule in heavenly halls,

and on earth for many days, offer holy incense to Jove.

Germanicus here refers to a soubriquet assumed by the Emperor Domitian after defeating a minor German tribe. It was an unnecessary war, criticized in his time as being waged only for Domitian’s self-glorification. The emperor then renamed the month of September Germanicus to honor himself and join the deified icons of a century previous, Julius Caesar and Augustus, on the calendar.

The idea of an afterlife in heaven among the gods preceded Christianity in Imperial Rome. But it was an honor posthumously conferred by the Senate on worthy emperors, more metaphor than belief. Domitian was notably impatient for divinity and insisted on being addressed as Dominus et Deus (Lord and God). His megalomania, paranoia, whimsical executions, and property seizures inspired both fear and hatred among the Roman elite. His gratuitous cruelty finally led to his murder by his household staff, with the reputed complicity of his wife. The Senate declined to apotheosize him. Instead it formally declared his memory “damned,” tearing down his statues and reminting his coins.

Martial has been criticized for his occasional toadying to Domitian and the above couplet might be taken as a prime example. I think it may represent something entirely different — what Martial’s friend, the noted grammarian Quintilian, labeled emphasis, a technique “in which we wish to incite a certain suspicion without actually saying it.”

I think you have to ask yourself who Martial’s real audience was. The flattered Domitian could read the lines one way, but to Martial’s circle of sophisticates — writers like Quintilian, Juvenal, and the literati-patron Senators Pliny, Stella, and Apollinaris — would this couplet be ode or epigram? If there’s such a thing as damning with faint praise, there’s also damnation by ridiculous praise: “Not only is Domitian going to heaven, he’s going there to rule over almighty God. And he’s just stupid enough to love this poem…”

Then you have to ask yourself who’s “saying” the lines. To use a modern-day analogy, is it the vice president or, say, Trevor Noah asking the president, “How did you come up with all those loaves and fishes to feed the tens of millions at your inauguration?” Could the poetic maestro who wrote the following couplet, intend the “Incense” couplet to be taken at surface value?

XII, 13

Genus, Aucte, lucri divites habent iram:

odisse quam donare vilius constat.

The privileged, Auctus, rage and prosper.

Hate costs nothing, benevolence is expensive.

V. Predecessors

Michael Wolfe’s volume provides a nice overview of the Greek epigram in both the Hellenistic and subsequent Roman periods. Classical Roman culture was Graeco-Roman, and Roman education included learning Greek and studying Greek literature. Just as Horace took pride in adapting Greek meters to Latin verse, Martial was well aware of Greek master epigrammists such as Leonidas and Callimachus. And, like Horace, his appropriations went well beyond imitation of Greek models. The expanding Roman Empire incorporated its Greek predecessor into something both larger and new, and Latin literature created its own new world.

If we consider Martial as the center from which Latin epigram radiates, who were some of his Latin predecessors? This short Horace poem isn’t epigram per se, but it has a bit of epigram-attitude. It lives in its own skin and doesn’t take itself too seriously. It gently mocks both the gods and those who invoke them. Its charm is in its brevity.

Odes: I, 30

O Venus regina Cnidi Paphique,

sperne dilectam Cypron et vocantis

ture te multo Glycerae decoram

transfer in aedem.

Fervidus tecum puer et solutis

Gratiae zonis properentque Nymphae

et parum comis sine te Iuventas

Mercuriusque.

Oh Venus, queen of Gnidus and Paphos, spurn

your beloved Cyprus and transfer

to this charming little household shrine where Glycera

calls you with clouds of incense. Bring

your wild boy Cupid and your troupe of Graces

and nymphs half out of their dresses.

And — because they’d just be bored

without you — Youth and lucky Mercury.

But it lacks a certain shadow, that minor key harmonic that Latin epigram taps from its cemetery roots. This isn’t the case with the work of another first-century BCE poet Martial frequently cites as an influence. Although also not designated as “epigram” per se, Catullus’s Carmen 47 seems to qualify. It has irony, darkness, plus a certain danger (in that Piso was Julius Caesar’s father-in-law and close ally).

Porci et Socration, duae sinistrae

Pisonis, scabies famesque mundi,

uos Veraniolo meo et Fabullo

uerpus praeposuit Priapus ille?

uos convivia lauta sumptuose

de die facitis, mei sodales

quaerunt in trivio vocationes?

Porcius and Little Socrates: Piso’s underhanded

pair of extortioners, itching to starve the world.

Did that hard-on, that fucking Priapus, promote

you over my dear Veraniolus and Fabullus? So

you can host elegant, sumptuous banquets in

the middle of the day, while my compadres

wander the streets, waiting for an invitation?

Carmen 47 also demonstrates what became one of Martial’s signature skills — crude street language seamlessly woven into elegant meters. Catullus wrote a number of diatribes against friends and adversaries alike, but many of his love poems also exude the dark brevity of epigram. There’s the famous Carmen 70:

Nulli se dicit mulier mea nubere malle quam mihi, non si se Iuppiter ipse petat.

dicit: sed mulier cupido quod dicit amanti,

in vento et rapida scribere oportet aqua.

No one else — my woman says — she’d rather marry

than me, not even if Jupiter himself proposed,

she says. But what a woman says to a lover in

heat, write on the wind, on the rushing waters.

As it happens, Catullus also offers an alternate version in his equally famous Carmen 72, that may help point up some differences between epigram and lyric.

Dicebas quondam solum te nosse Catullum,

Lesbia, nec prae me velle tenere Iovem.

dilexi tum te non tantum ut vulgus amicam,

sed pater ut gnatos diligit et generos.

nunc te cognovi: quare etsi impensius uror,

multo mi tamen es vilior et levior.

qui potis est, inquis? quod amantem iniuria talis

cogit amare magis, sed bene velle minus.

Back then you’d say Catullus is the only friend who gets me,

that you’d rather be in my arms than almighty Jove’s.

I cherished you then, Lesbia, beyond any ordinary lover, as

proudly as a father cherishes his sons and sons in law.

Now, I truly know you. And I’m ashamed to be

burning more than ever for someone so shallow, so tawdry.

That’s the irony, sweet. A wound this deep turns love

to helpless compulsion, destroys any real affection.

These are both tour-de-force poems, and one doesn’t need to choose between them. But they enter and leave what seems the same bedroom through different doors, depositing the reader in different anterooms. Carmen 72 provides a detailed dissection of Catullus’s great love gone sour. You can feel the dynamics of the initial connection between the twentysomething poet and the thirtysomething, married, aristocratic adventurer who is sexually initiating him. And then the Icarus-like crash to earth. It’s stunning lyric poetry, no less so, I think, because at the end it’s forced into song-stripped, brutally honest prose.

Conversely, Carmen 70 compresses itself into half as many lines. Its lovers have no names; their identities consist only of the encounter and their eager talk. Unlike Lesbia’s free-woman aspirations in 72, the mulier of 70 is “my woman,” and the chatter is of marriage, not friendship. The epigram version doesn’t conclude with loss, but with energies so primal they preclude any possibility of human possession.

The speaker, in both poems, revels in being preferred over Jupiter. (And here I’m reminded of Martial’s similar flattery of Domitian.) That hubris, of course, is unsustainable, and Carmen 72 descends into a brooding bathetic pain. Carmen 70’s pared-down brevity, on the other hand, catches the wind, soars, flows with the currents. The speaker’s pain is redeemed by the poet’s Jove-like mastery of the wild elements.

VI: Elegy and the Anticlimactic Climax

If the Latin epigram is a child of gravestone epitaph, I’d argue its other funerary parent is Greek elegy. The mourning “elegiac couplet” is Martial’s go-to meter and, in my no-doubt biased opinion, adds a lyrical component to his dark humor that isn’t found in the, say, 18th-century English epigrams of Pope, Dryden, et al.

Let me preface what follows with some caveats. First, my Latin scansion skills are crappy, and I also distrust those scholars who profess to know so much about 2,000-year-old pronunciation. So I don’t generally try to consciously count the beats when translating. Nor do I find trying to replicate source language meter particularly helpful in producing an enjoyable interpretive translation. What I do try to bring across is the “voice" of the original in a sort of eye-metric, opera-surtitle companion to the Latin.

That said, it’s worth thinking a bit about what the elegiac couplet does to advance the Latin epigram. It’s oversimplification to characterize the meter as a six-beat line, followed by a five-beat response. But for our purposes, it’s enough to illustrate the implicit mourning voice in the second line’s fading cadence. Coleridge, translating Schiller, penned an illustrative poetic definition:

In the hexameter rises the fountain’s silvery column,

In the pentameter aye falling in melody back.

The last couplet of Catullus’s Carmen 70 is also a good example:

dicit: sed mulier cupido quod dicit amanti,

in vento et rapida scribere oportet aqua.

“[W]rite on the wind, on the rushing water.” As much as that last line soars, it takes its strength from an imagery of ungraspable dissolution, as well as offering a powerful instance of what happens when etched epitaph successfully merges with sung elegy. Not all Latin epigrams are written in elegiacs, but when they are, the voice can take on a certain richness akin to music in a minor key. (Here, we might note that the elegiac was also a preferred mode of Latin love poetry, a good deal of which was no stranger to lament.)

Let’s revisit Mae West’s twist on Alexander Pope’s 18th-century English aphorism. Pope’s original (not an epigram per se, but extracted from a long didactic poem) is half of a “heroic couplet” — two rhyming, decasyllable pentameter lines:

Good-Nature and Good-Sense must ever join;

To err is human, to forgive divine.

Each line comes to its own firm conclusion, and except for rhyme the second line could be read as it’s own “couplet,” with short lines of five syllables each:

To err is human,

to forgive divine.

Mae West, I’d argue, seduces Pope’s theology with a sly syncopated lilt. When minimally altered and recast in a faux elegiac, with the omission of “but,” her divinity reigns in a somewhat earthier heaven:

To err is human,

it feels divine.

VII. What Makes an Elegy an Epigram? And Vice Versa

Martial labeled all of his 12 main volumes “Epigrams,” even though they included a wide variety of poems on a wide variety of subjects. Some, while in clear elegiac voice, mourn not for the dead but for characters living on the dark side. Their minor key music imparts a bluesy empathy that elevates the poem from mere salacious mockery. This one is pure epigram:

XI, 87

Dives eras quondam: sed tunc pedico fuisti

et tibi nulla diu femina nota fuit.

nunc sectaris anus. o quantum cogit egestas!

illa fututorem te, Charideme, facit.

You were rich, Charidemus, but started craving it

in the ass. Women ceased to exist for you.

Now, you’re working the widows. Ah, what poverty

makes us do. It’s even made a stud of you.

The following commemoration addressed to the widow of the poet Lucan, whose suicide was commanded by the Emperor Nero, is, on its face, an elegy. But in its brevity, irony, and invective, it might also be taken to demonstrate the variety of uses epigram can serve.

VII, 21

Haec est illa dies, magni quae conscia partus

Lucanum populis et tibi, Polla, dedit.

heu! Nero crudelis nullaque invisior umbra,

debuit hoc saltem non licuisse tibi.

Today we commemorate a great birthday, the day

that gave Lucan to humanity, and to you, Polla.

Damn it, vicious Nero, for no ghost more despised, this

victim, at least, you shouldn’t have been allowed.

That same slippage between lament and epigram applies to an earlier Martial poem from which he cadged that last phrase about Lucan.

IV, 44

Hic est pampineis viridis modo Vesbius umbris,

presserat hic madidos nobilis uva lacus:

haec iuga quam Nysae colles plus Bacchus amavit,

hoc nuper Satyris monte dedere choros.

haec Veneris sedes, Lacedaemone gratior illi.

hic locus Herculeo nomine clarus erat.

cuncta iacent flammis et tristi mersa favilla

nec superi vellent hoc licuisse sibi.

Remember Vesuvius, so green, so vine-shaded, its

wine presses overflowing with noble grapes. Bacchus

came to love those ridges more than his childhood Nysa hills,

this mountain where elusive satyrs were said to dance and

sing. And Venus preferred its slopes to her Spartan temple,

as she lingered in the breeze above Hercules’s namesake city.

Now, everything is ruin, overwhelmed by fire, ash, and grief.

Even the almighty gods regret they were allowed to do this.

VIII. Do We Have Anything Like This Now?

Since at least the 18th century, the epigram as adapted into English has seemed to prefer a certain jaunty regular beat and rhyme. To wit, Alexander Pope’s dog-collar inscription couplet:

I am his Highness’ Dog at Kew.

Pray tell me Sir, whose Dog are you?

The irony and subject matter certainly have their Latin and Greek counterparts. But the English poet’s voice incants in a major, not minor key. The Romantic period, especially Byron, may do a little better, as in this piece on the revolutionary (and atheist) Thomas Paine’s bones being smuggled to England from New York by an admirer who wanted to enshrine them in an anti-Royalist monument.

In digging up your bones, Tom Paine,

Will Cobbett has done well:

You visit him on earth again,

He’ll visit you in hell.

There’s more darkness in the cynicism here, but the Christian cosmology (even if offered by someone like Byron) still seems a bit too jaunty for the Catullus-Martial model. In the early 20th century, Robert Frost offered this often quoted gem.

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

This, I think, comes a bit closer to Latin epigrammatic lament: funereal subject matter, a nicely designed rhyme scheme that dances rather than hops, and a fading rather than emphatic ending. Its agnostic cosmology evokes the earthquake-shaken pantheon of Martial’s Vesuvius poem.

But for all this, Frost’s “Fire and Ice” lacks one of the Latin epigram’s touchstones — a grounding in a particular reality. Frost’s disaster is remote and conjectured, Martial’s is a catastrophe in his lifetime, the pleasure-mountain of Vesuvius having exploded a mere decade before his poem was written. Frost’s irony is clever, Martial’s a personal indictment of the mythological order of things.

I’m sure there are others, but I’d like to conclude with an — on its surface — unlikely English-language poem that seems to me to touch all the bases of the Latin elegy as epigram. I say “unlikely” because we’ve been talking about elegy’s musicality and cadence, and the poem I’m thinking of doesn’t look like that kind of melody on the page.

But first I’d like to offer another Martial poem for contrast. This one is more elegy than epigram, but what keeps it epigrammatic is the way it pulls the dynamics of Roman society into its mourning, conflating dual themes of slavery and death. On that note, the modern reader should be wary of conflating the eugenic and ideological components of American slavery with slavery in the Classical world. For all its inherent injustices, Roman household slavery had no racial basis and was often the first rung on the Roman patronage system ladder. By Martial’s time, a huge percentage of Rome’s population traced its ancestry to manumitted slaves, many of whom became very wealthy. Freed slaves became their former master’s “clients,” the master their “patron” — a relationship that implied commercial sponsorship, mutual protection, and benefit.

I, 101

lla manus quondam studiorum fida meorum

et felix domino notaque Caesaribus,

destituit primos viridis Demetrius annos:

quarta tribus lustris addita messis erat.

Ne tamen ad Stygias famulus descenderet umbras,

ureret implicitum cum scelerata lues,

cavimus et domini ius omne remisimus aegro:

munere dignus erat convaluisse meo.

Sensit deficiens sua praemia meque patronum

dixit ad infernas liber iturus aquas.

Demetrius — whose faithful penmanship

captured his master’s eager verse in a hand

even the Caesars recognized — is gone. In the

very bloom of youth, plucked in the autumn of

his twentieth year. Tangled in fever and gnawed

by plague, I couldn’t let him descend to the caverns

of the Styx a slave. I ceded my rights, praying

the ceremony might somehow even heal him.

He sensed the gift, smiled, whispered Patron,

and embarked, free on those sunless waters.

IX. Freedom

Robert Frost notably quipped that free verse was akin to playing tennis “with the net down.” But I think all poetry might be characterized as striving for language that talks back to you. And if successful free verse forgoes the net, it allows for a greater variety of back and forth volleys. Its meter and form don’t resemble any of the epigrams we’ve looked at so far. But step back a bit from this E. E. Cummings masterpiece and ask yourself: what aspect of elegy as epigram it doesn’t have?

Buffalo Bill ‘s

defunct

who used to

ride a watersmooth-silver

stallion

and break onetwothreefourfive pigeonsjustlikethat

Jesus

he was a handsome man

and what i want to know is

how do you like your blue-eyed boy

Mister Death

¤

¤

[1] Except where otherwise indicated, translations are my own.

LARB Contributor

Art Beck is a poet, essayist, and translator with a number of university and small press journal credits, as well as volumes of both original poetry and translations from the late 1970s onward. His Opera Omnia or, a Duet for Sitar and Trombone — versions of the sixth-century CE North African Roman poet Luxorius, published by Otis Books — won the 2013 Northern California Book Award for translated poetry. Mea Roma, a 130-some poem “meditative sampling” of Martial’s epigrams was published by Shearsman Books in 2018. The Insistent Island, an Odyssey-themed original poetry chapbook, was published by Paul Vangelisti's Magra Books in 2019. From 2009 through 2012, he was a twice yearly contributor to Rattle since discontinued e-issues with a series of essays on translating poetry under the byline The Impertinent Duet.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Dante’s Psychological Comedy

D. M. Black finds psychological depth in Dante’s “Comedy” and shares excerpts from his translation of “Purgatorio.”

The Secret Song of Water: From Coleridge to Darwish

Fady Joudah reflects on water as substance, poetic subject, and way of life.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!