Land of Milk and Money

Mark Goble tries "The Dairy Restaurant," the new graphic history from Ben Katchor.

By Mark GobleAugust 31, 2020

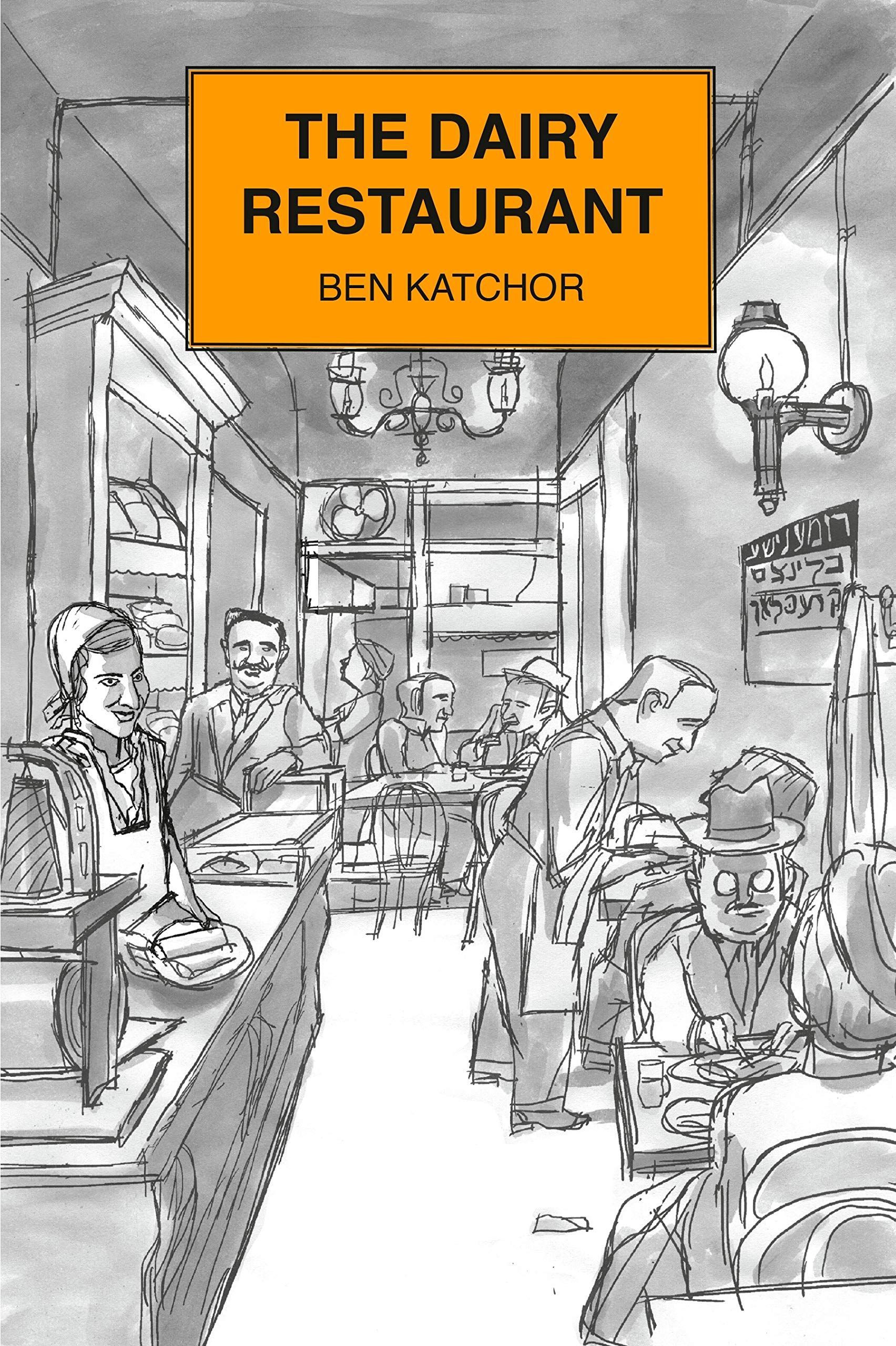

The Dairy Restaurant by Ben Katchor. Schocken. 496 pages.

MY FAVORITE RESTAURANT is closed right now and so, I’m willing to bet, is yours. My second favorite place is closed too, just like my third favorite; the taqueria down the street; the expensive Japanese place downtown where I only eat for “business”; the best Thai place; the bad Thai place right next to it, with almost the same name, that has inexplicably survived for years; the burger place; the new falafel place that I worried was going to hurt the old falafel place; and the old falafel place that I hardly ever went to anyway but assumed would still be there when I at last decided to try it again.

This isn’t to say that everywhere is closed, of course, and since I live in the East Bay where we’ve been sheltered-in-place for months, the take-out protocols are almost a reflex — and still bring a small charge of camaraderie whose limits are obvious, since paying for food, despite how it feels right now, is the very definition of business as usual. So far I’ve avoided the more or less vulturous delivery services, though this may say more about the luxuries at my disposal (time, good weather, short distances to travel) than my own virtues. Still, within limits — limits that I couldn’t have imagined a few weeks ago but that now feel like immutable laws of physics — I could have almost anything I’d want for dinner tonight. As comforts go, this isn’t so much cold as weird, since what I really want for dinner — like, I’m guessing, you — is somewhere, anywhere else to be.

Restaurants make it easy to sentimentalize the everyday brutalities of capitalism because the ones we come to love also manage to obscure all the economies — the prices put on things like pleasure, sustenance, hospitality — that, were they plainly visible on the menu, would leave us queasy. Some restaurants traffic in nostalgia, performances of tradition and identity, aesthetic aspiration, or sense of place. Others trade in service, convenience, reliability, and industrial scales of standardization. As businesses, they almost invariably run on preciously small margins. With up to seven million restaurant and food service workers likely to lose their jobs in the coming months, the current crisis is registering as an extinction-level event. Highly visible chefs like David Chang and Tom Colicchio have made the case that massive levels of government support will be required for most restaurants to survive if they are not part of well-capitalized franchises or linked to the networks of investors that sustain the most prestigious fine-dining enterprises.

Variations on these themes — with more swearing — are familiar to anybody who follows these and other cooks and chefs on Twitter or Instagram. (Chris Cosentino debones a chicken. Chris Costenino guts Ruth’s Chris Steak House.) But as Dirt Candy’s chef and owner Amanda Cohen points out, the post-coronavirus restaurant landscape is going to look very different not because the epidemic has suddenly brought the long post-recession recovery to a stop, but rather because it has accelerated the slow-motion catastrophe that was happening all along. “Customers are willing to pay only so much for food,” Cohen writes,

yet rent, utilities, insurances, taxes and food costs keep going up. We’ve survived by cutting our labor costs to the bone, but that has left us in the industry still on the edge, while cooks, porters, servers, dishwashers, and bartenders have no significant savings, health care or a safety net.

It’s been almost 25 years since I last worked in a restaurant, and I was just passing through on my way to graduate school. What Cohen is describing, though, is a process of deliberate immiseration in the face of declining rates of profit that, with only minor substitutions — swapping chard for kale, as it were — could apply to deans and provosts talking about state disinvestment in higher education, or media companies pushing layoffs as a response to falling ad revenues. This is not to say that restaurant workers, contingent faculty, and freelancers are subject to the same economic pressures, nor that they represent a class in any strict sense of the term. Still, the current crisis has exposed just how many industries were operating at the very limits of enforced precarity already, and part of the shock at seeing so much now at risk is recognizing how close to ruin it all was before.

¤

In one of Capital’s more homiletic passages, Marx writes that “the taste of porridge does not tell us who grew the oats.” Of course, this is something that a lot of restaurants will gladly tell you now, from farm to table to Portlandia joke. But no one can tell us what restaurants will be here when this is over. I don’t know if Ben Katchor’s favorite restaurant is closed right now, but his new graphic history The Dairy Restaurant makes me think that many of the eating places he treasures most have been gone for years and even centuries. His new book is, above all else, a dauntingly complete history of restaurants that served various kinds of Eastern European milchig cuisine to generations of mostly Ashkenazi Jews — who, keeping kosher, observed strict dietary laws designed to separate the consumption of all dairy products from any sort of fleishig food containing meat. Blintzes, matzo brei, kreplach, kasha varnishkes, and knishes, along with “pareve” dishes like gefilte fish, lox, and pickled herring that are permissible with milk or meat, as well as “mock” liver salads, mushroom “cutlets,” and other delicious simulacra: a world of Jewish food that still appears on deli menus, especially on the East Coast, but has not achieved the ubiquity of bagels, nor the resurgence of pastrami or Montreal smoked meat, and definitely not the glossy acclaim of contemporary Israeli cuisine as it’s been popularized by such chefs as Yotam Ottolenghi, Einat Admony, Alon Shaya, Michael Solomonov, or Adeena Sussman. Notwithstanding the gaudy fuchsia spectacle of a good borscht, these are foods that are far richer in calories than colors. This isn’t to say that a plate of fried matzo — a beige-on-beige masterpiece consisting of little more than water, fat, and carbohydrates — is anything but indulgent.

But even the voluptuousness of the cuisine that Katchor celebrates so sincerely in The Dairy Restaurant — thick yogurt, fresh cream, butter by the metric ton — can look deceptively austere and plain, its dense and complex minimalism uncannily well suited to the monochromatic washes and blocky shapes that mark Katchor’s style of drawing. He eventually returns to a familiar cultural palate too, with 20th-century New York and its many types of Jewish character looming always at the end of whatever far-flung explorations of Persia, Palestine, Czernowitz, or Odessa we make on our way to the Lower East Side. It’s easy to picture Katchor’s “Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer” enjoying the noodles and kasha at the Famous Dairy Restaurant on West 72nd Street, right next to Isaac Bashevis Singer — who, as Katchor relates, couldn’t be nudged into giving bigger tips despite his Nobel Prize. As in Katchor’s first book from 1991, Cheap Novelties, the “pleasures of urban decay” — and in particular the fading infrastructures of Jewish and Yiddish life in postwar New York — are excavated with almost fetishistic care and deadpan pathos. I’ll admit that the image of Zero Mostel, still blacklisted, at Steinberg’s Dairy Restaurant blowing “straw wrappers at other diners during the run of Ionesco’s Rhinoceros” does not exactly capture the future of communism. If you are trying to cut down on your consumption of nostalgia, The Dairy Restaurant is not for you. Yet there will be eating of knishes in dark times too, and one could do worse than to remember just what brought figures like Mostel and Harry Belafonte together at Steinberg’s.

Some of the connections Katchor traces between radical politics and milchig eating are literally underground: from a dairy shop he opened under an assumed name, Russian revolutionary Yuri Bogdanovich plotted the assassination of Tsar Alexander II, hiding the dirt from tunnels dug beneath the street to plant a bomb for the tsar’s carriage in barrels that Bogdanovich told the police were full of milk. Emma Goldman briefly operated an ice-cream parlor in Brownsville, Brooklyn. Lenin spent several weeks in 1916 at a Swiss sanatorium where he was restricted to a diet consisting almost entirely of milk, bread, butter, and cheese, hoping that the faddish “milk cure” of the time — which also allowed for a little fruit but required a lot of enemas — would help his wife’s thyroid problems. With Tolstoy’s ardent vegetarianism as a model, many radicals and intellectuals of the early 20th century embraced eating habits that sometimes merely paralleled but, on many occasions, self-consciously emulated the sacred rules and regulations of traditional Jewish cuisine and religious practice. As Katchor describes, as early as the 18th century Rousseau and the French Physiocrats invoked the idea of the Mosaic covenant and its Talmudic elaboration into the principles of kashrut as a powerful resource for imagining new and more enlightened visions of human relations to the natural world. So when John Reed finds himself at a vegetarian restaurant in Moscow with the amazing name “I Eat Nobody” — chew on that one, Moosewood and L’Arpège — he is, for Katchor, dining in the wake of several thousand years of Jewish thinking and arguing about the ethics of food and being human. Reed probably enjoyed a quieter meal than the one Katchor relates in which Clement Greenberg, Delmore Schwartz, and other Partisan Review staffers, dining at Ratner’s on Second Avenue in 1946, had it out with Philip Rahv over his prickly style of management.

When Katchor is telling stories like these, there is precious little to distinguish his melancholy yiddishkeit from his historical method. Near the end of The Dairy Restaurant, Katchor practically admits as much. He writes that when he told a “professional historian” that he was conceiving a book whose narrative would span the period from the Garden of Eden to the Lower East Side by way of the laws of kosher, the Jewish diaspora, and the rise of the modern dairy industry, the historian suggested that he “get a grant,” hire some graduate students, and “put them to work.” Katchor confirms that he instead “took the milekhdike approach and ruminated over the subject for many years” before eventually finishing the project.

The joke lands on several levels — as it should, considering that Katchor spends almost 300 pages on the setup. This is not the first time in The Dairy Restaurant, after all, that Katchor has ventured a connection between a type of Jewish personality — persistent but recessive, stubborn but pacifistic, retiring but potentially revolutionary — to the digestive process of the cows who give the milk that gives his characters their character. The model of the milkehdike is Tevye from the Sholem Aleichem stories, which, for Katchor, got ultra-pasteurized, so to speak, in the process of becoming the musical Fiddler on the Roof (which, it should also be said, helped bring Zero Mostel in from the cold). What Katchor admires in Tevye, the long-suffering, unquiet dairyman, is the sheer dialectical exuberance of his passions, which lack the bloodlust of a true carnivore (whether Cossacks or Lazar Wolf, the butcher who hopes to marry Tevye’s daughter), yet are exquisitely, existentially insatiable nonetheless. In Katchor’s version of Aleichem, we get a chance to remember that Tevye’s sufferings on stage and screen are rendered somewhat milquetoast when compared to all he undergoes. But Katchor also suggests that the occasionally comic bluster of Tevye’s piety is itself a reflection of “the technical necessities” of different dairy practices, from the professions of purity that were needed to inspire consumer confidence before refrigeration and pasteurization, to the obliging friendliness that evokes “the desire to establish a benevolent relationship” with animals that can increase productivity. There isn’t quite enough autobiography in The Dairy Restaurant to say for sure that Katchor sees himself as strictly milekhdike, but it’s hard to “ruminate” over this passing encounter with a “professional” historian without wondering what Katchor actually thinks about the advice to “get a grant.” As the first graphic novelist to be named a MacArthur Fellow, Katchor should be nobody’s schlemiel.

The Dairy Restaurant does much more than simply revisit the Jewish landscapes of New York that provided Katchor with so much of the material for his terrific early works. If the figure of Julius Knipl captures the restless urban sensibility of the classic flâneur in midcentury Jewish drag — a Borscht-Belt Baudelaire on the prowl for gefilte fish, not prostitutes — The Dairy Restaurant operates on a far vaster scale, one that evokes a different side of the work of Walter Benjamin. From 1927 until his death in 1940, Benjamin — the scholar of 19th-century Paris largely responsible for enshrining the flâneur as a figure of urban engagement in our collective imagination — assembled the notes and fragments on the French capital that would become The Arcades Project, at once a work of material history at its most concrete and a project of imaginative reconstruction at its most fantastic. Similarly, some of the most strangely moving sections of The Dairy Restaurant unfold across pages and pages of brief listings that document the many milkhiger establishments that Katchor has discovered in his archival wanderings.

But where Benjamin’s mode of attention was scattered and distractable, Katchor’s devotion is profoundly monotheistic in its pursuit of dairy restaurants. Most operated in New York, and most sound almost identical, with names identifying their proprietors (“Harris Rosenzweig’s Kosher Milkhiger Restaurant,” “A. and S. Ashkehazi’s Strictly Kosher Milkhiber Restaurant, Baker, and Dairy Lunch”), their cuisine (“Unique Dairy Restaurant,” “Palm Vegetarian and Dairy Restaurant”), or, best of all, the utopianism of their collective ethos (“The Public Art Dairy Restaurant,” “Rational Vegetarian Restaurant,” “United Knish Factory”). Some entries spill out as anecdotes about their owners’ lives or noteworthy customers, their shared narrative arc from thriving ethnic eateries to all-but-vanished relics left behind by decades of assimilation, urban renewal, and gentrification. Yiddish newspaper ads and photocopied menus fill the corners of the pages like a scrapbook, while Katchor’s drawings give us exterior shots of dairy restaurants from Baltimore to the Bronx, Toronto to Miami. And this is before an “In Memoriam” list of places Katchor has read about in passing or seen in old New York telephone directories. These “undocumented dairy restaurants” must also be remembered here, Katchor tells us, since otherwise “not even a matchbook remains.”

Katchor offers several reasons why these restaurants are worth such intense — maybe even obsessive — attention. The most obvious is the most terrible: “Six million people with a taste for the Eastern European dairy dishes mentioned in this book were murdered in Europe during World War II.” I have to say that I was waiting for this moment long before Katchor finally arrives at it, almost in passing, near the end of The Dairy Restaurant. But what Katchor mourns in The Dairy Restaurant is not just the Jews of Europe whose history and cuisine he tracks from the Middle Ages to the Holocaust. He is also trying to reckon with the fading of the world that the destruction of this other world had made in the United States. It is the postwar flourishing of dairy restaurants in New York — which through the 1970s, Katchor writes, “had seemed to be an eternal presence” in the city — and then their rapid and seemingly inevitable disappearance that structures his perspective on Jewishness in this book. Katchor might be sad that there are fewer places for gefilte fish or kasha in 21st-century New York, but these dishes are also metonyms for a passing way of being diasporic. These dishes, in other words, symbolize some of the milekhdike dimensions of Jewish thought and politics that Katchor fears are being pushed aside.

Katchor begins his narrative of Jewish eating practices with the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, suggesting — at the level of metaphor, if not theology — that the extrapolation of the laws of kosher from a few scant mentions in the Torah responded to the way that rabbinical academies and Talmudic authority came to take the figurative place of the hereditary priesthood and the practices of animal sacrifice left behind with the loss of Jerusalem. Under the conditions of diaspora, the ornate and sometimes absurd laws of kosher — in tribute, Katchor writes, to “YHVH’s obsessive-compulsive need to keep diverse things separate” — become highly portable rituals of identity and belief, acts of consecration on-the-go for a people who can’t be sure when and where they will be fleeing next.

It thus makes sense that much of Katchor’s focus in the first half of The Dairy Restaurant is on variously wandering Jews who improvise the foundations of commercial milchig eating to let travelers keep kosher while away from home. Kosher restaurants provided not just food but also psychic and emotional relief for visitors who often had good reason to be anxious about the kindness of gentile strangers. And for observant Jews, dairy restaurants were safer still since their proprietors had already forsworn serving meat, minimizing the chances of any guests accidentally consuming treif and stressing their commitment to a minority cuisine and culture. Dairy restaurants — by the hundreds, over centuries, speaking in Yiddish shot through with other local tongues — offered worldly and gustatory versions of the symbolic “Jerusalem” where Jews promise they will be for Passover (next year) when the Seder ends.

Many Jews, of course, increasingly find this promise hard to swallow, and American Jews often substitute this line in their Haggadahs like a healthy-ish diner choosing salad over fries. The fries, just to be clear, are Zionism. Katchor still finds the occasional Eastern European dish on the menus of the many kosher pizzerias that have flourished in New York in recent decades. These are places where the pastoral dreams and “agricultural possibilities” of the dairy restaurant — an expression, he admits, of the Zionist project that once spoke to “the constrained urban life of European Jews” — are revealed to possess “all the modern brutal trappings of a modern nation state.” The ubiquity of falafel, however delicious, suggests to Katchor not the milekhdike laments and pleasures of a dairy meal with Zero Mostel, but instead the “macho atmosphere” of a settler population “physically occupying an actual piece of Palestine, that mythical land of milk and honey.” The food is just as vegetarian, but the appetites now seem a little too carnivorous.

Looking back to the bygone dairy restaurants that were still there for him to visit in the 1970s and 1980s, Katchor finds that “now that they are almost completely gone,” he and other Jews have “experienced a second expulsion from a kind of paradise.” First the Garden of Eden, then Mrs. Stahl’s Knishes, shut down. Katchor’s Jews can’t catch a break. Or maybe we should take Katchor’s hyperbole at closer to face value and be glad that every dairy restaurant — from the first Persian garden he posits as a model for the Torah’s Eden to Ratner’s on Delancey, the only dairy restaurant in his book that I visited before the fall — was already paradise enough, not because it catered to every craving and desire that human beings can have, but because it offered something of a break from the rapaciousness of the world it kept outside.

Or we can take the Eden metaphor in yet another way. If dairy restaurants gave their customers “a culinary respite from the larger meat-eating world,” they were still not really the oases or utopias their advertising promised. No such place exists for Katchor, and in his reading of Genesis, there is no time before the time when some people exploited others for at least a little gain. “Even before the invention of money,” Katchor theorizes, “the Garden of Eden remained a circumscribed business arrangement.” It was the “narrative invention” of a people who had already lost a lot, and tried to “postulate the existence of a man before the existence of social and class categories.” But the vision gets compromised almost from the very start when the “model of the sole proprietor is transformed into a god.” G-d doesn’t simply tell the guests what’s on the menu, but lets on that there are special dishes they are not allowed to taste, for reasons that remain obscure.

“The course of human life is no more, or less, altered,” in the gospel according to Katchor, “in countless restaurants and cafes, by people ordering the ‘wrong’ things, waiters and bouncers waiting to do their job, and owners looking on with a mixture of motherly love and proprietary scorn.” Yet such is the boundlessness of Katchor’s milekhdike reluctance to condemn and judge — to indulge in any absolutes that might butcher “rumination” and reflection — that YHVH’s arbitrary shows of force are considered, reconsidered, and revisited until they make a kind of sense, even if they never really seem fair. This is why Katchor spends so much time with Alecheim’s Tevye: not just because he is the most famous Jewish dairyman and the only one, to be honest, who’s left much of a mark outside the shtetl, but also because his interminable “on the other hand”–ing is finally a reminder that there might not be any justice where there is power over someone else. Maybe better to act too late, or not at all, than take what isn’t yours. The dairy restaurant is a spectacular construction of self-imposed limits and sacrificed desires. And in this way, Katchor beautifully persuades, it was as much holy land as anyone should ever want or claim.

The Dairy Restaurant ends not so much in mourning as in a kind of suspended sense of sadness and wonder — sadness for all these eating places that no longer are; wonder that they existed in the first place, and lasted for so long. The waning of the Jewish diaspora’s ethnic character, outside the worlds of the Orthodox, put the decline of the dairy restaurant in motion, and it has been accelerated by the turn away from dairy eating generally. It’s hard to imagine anything less “paleo” than a blintz. And though the dairy restaurant is vegetarian in every way, Katchor of course notes that its cuisine is “as deeply implicated in the earth’s environmental death spiral as the meat industry.” The final drawing of the book shows two figures standing in the ankle-deep waters of a flooded city, with a Shell station in the background that has become a “Tofu Burgers” stand. “Are you hungry?” asks one of the figures to his companion. He’s speaking Yiddish but, like his friend, he also wears a gas mask: milekhdike persistence and sardonic gloom in a charmingly dialectical image. Giant mosquitoes hover about these potential diners’ heads, a dystopian joke about ecological calamity that Katchor couldn’t possibly have known would, by the time The Dairy Restaurant was published, look eerily like a picture of the present epidemic.

But this very Yiddishe book’s last words actually borrow from another ancient language. Katchor offers the Latin phrase “Et in Arcadia ego” as a closing benediction to the reader who has followed him from the Garden of Eden to whatever waits for us after the next great flood. Translated as “even in Arcadia, there I am,” this phrase is conventionally said to refer to death’s inevitable presence in the landscape, no matter how idyllic. This is why Poussin takes it as the title of his famous 17th-century painting of a group of shepherds around a tomb which has been placed, for no reason we can see as viewers, in the middle of a charmed pastoral scene. Katchor actually draws his own versions of two Poussin paintings earlier in The Dairy Restaurant, an art historical appropriation that at first glance feels discordant in a book devoted to altogether less imposing masterpieces of human consolation like potato pudding and maatjes herring. But there’s clearly more than one way to mourn, and Katchor has rendered his experience of loss into a monument, worthy of its sweep and scale for all its humble themes.

When my favorite restaurant goes away, however, I won’t blame YHVH or coronavirus. I’ll blame a landlord or a bank. And since I don’t keep kosher, I’ll be out for blood.

¤

LARB Contributor

Mark Goble is associate professor of English at the University of California, Berkeley, and the author of Beautiful Circuits: Modernism and the Mediated Life.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Isaac Bashevis Singer: Writer and Critic

David Stromberg considers the long-neglected critical writings of Isaac Bashevis Singer.

It Takes a Deep Reading. And an Obsession.: An Interview with Paul Karasik

Alex Dueben talks to Paul Karasik about teaching, Art Spiegelman, Martha's Vineyard, and his latest book, "How to Read Nancy."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!