“Know That I Am Perfectly Well and That I Always Find a Way”: The Revolutionary Letters of Che Guevara

Che Guevara was a prolific letter writer, and his words show his complexity.

By Joy CastroMarch 5, 2022

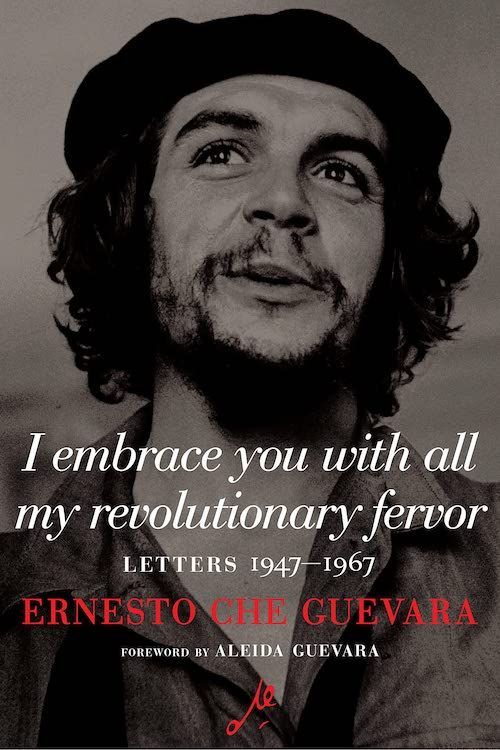

I Embrace You with All My Revolutionary Fervor: Letters, 1947–1967 by Ernesto Che Guevara. Seven Stories Press. 384 pages.

IMAGINE YOU HAD never seen the portrait by Alberto Korda — possibly the leftist world’s most famous headshot — in which a lean-jawed Che Guevara gazes resolutely toward a utopian future. Imagine you didn’t know Che was a doctor-adventurer who fought in global liberation movements before his martyrdom in Bolivia. Would his words stand on their own without the celebrity persona?

The answer is yes. I Embrace You with All My Revolutionary Fervor: Letters, 1947–1967 is a contribution to world history and a window into Guevara’s private life and literary style. Of its contents, 80 percent has never been available before.

Deftly edited by Havana scholars María del Carmen Ariet García and Disamis Arcia Muñoz, the volume forms part of an initiative by Seven Stories Press in partnership with Ocean, the legendary Melbourne publishing house, to produce new editions of Guevara’s complete works in both Spanish and English. This comprehensive paperback collection is graced (for those of us bourgeois enough to care about such things) with exquisite new designs splashed with tropical colors. A few volumes have already appeared; the rest will continue to be released over the coming months. Most of these works are familiar and have been in circulation for some time.

Yet the letters in I Embrace You, a hardcover, are a newly available revelation, and the red and grayscale dustjacket bears a photo of Che strikingly different from the revered Korda image. Captured in Cuba in 1959 by LIFE photographer Joseph Scherschel, the Che on I Embrace You is joyful, his lips smiling and slightly pursed to expel cigar smoke, the whiskering lines next to his eyes curved upward, his whole face lit with laughter.

This is also the Che who appears in the letters: lighthearted, gallant, and hopeful. To read them is to discover his humor, his courage, his frankness, his odd blend of arrogance and generosity, his wanderlust and his idealism, his willingness to subsume himself in the cause of freedom for the poor in Cuba, in Congo, and in Bolivia, where he was killed in 1967 on orders from Washington and the Bolivian government. “Above all,” he wrote to his children, knowing he was unlikely to see them again, “always be capable of feeling deeply any injustice committed against anyone, anywhere in the world.”

Chronologically arranged and helpfully glossed, the collection begins with his intimate letters to his mother, father, favorite aunt, and close friends as he chronicles his wild travels, his fascination with archaeology, his insouciant dismissal of obstacles, and an indifference to his own suffering, which would later serve him on the battlefield. In his sharp, clear, witty prose, you discover his irony, his love of poetry, his smooth shifts among registers — a writerly ease stemming from years of reading world literature.

From Bolivia, to his mother: “I fulfilled one of my most heart-felt desires as an explorer: I found, in an indigenous cemetery, a small statue of a woman, the size of a little finger…”

From Colombia, to his mother: “After a nice flight on a plane that shook like a cocktail shaker we arrived in Bogotá.” “We spent two nights in the loving company of mosquitos…”

From Peru, to his Aunt Beatriz, whom he loved to tease:

Unfortunately, it turns out that the Amazon is as safe as Paraná, and Purumayo as safe as Paraguay. This means I won’t be able to bring you a shrunken head as a gift […] I had also hoped to show off my qualities as a martyr, hanging around in the midst of malaria and yellow fever, but it turns out that they, too, no longer exist here. The situation is exasperating.

You detect his growing radicalization and his decision to fight. His missives to Fidel Castro in the midst of battle, with men on the ground and supplies running low, are earnest and meticulous. When Che was named to various posts in the fledgling communist government, the letters show how quickly he educated himself in his new homeland’s anticolonial history (he was granted Cuban citizenship in 1959), dropping references to 19th-century heroes Máximo Gómez and Antonio Maceo in his letters to fellow Cubans.

His invitations to writers elsewhere, imploring them to come see the new Cuba for themselves, bear a different tone than his sarcastic letters to insufficiently committed bureaucrats (“To clarify, putting myself at your level of comprehension: I’ll never consent…”), which are as ruthless as his battlefield reputation. In 1962, he begins signing his letters, “Homeland or Death. We will win.”

The letters toward the end of his life reveal the personal costs of commitment. To his parents in 1965: “I have loved you very much, only I haven’t known how to express my affection. I am extremely rigid in my actions…” However tender they may be, his letters to his children are tediously doctrinaire, and his letters to Aleida March, the fellow revolutionary whom he married, are peppered with nobly communist reasons he won’t be bringing her gifts from the places he visited as a diplomat for Cuba’s young government, excuses that would quickly strain some lovers’ patience.

Known since adolescence for his hypersexuality and many affairs, he was by all accounts faithful to Aleida, whom he married in 1959 and had four children with, and who now directs the Che Guevara Studies Center in Havana. Nonetheless, he could not resist needling his wife during his many diplomatic trips abroad: “I only want to tell you that I bought you a beautiful kimono that has a special enchantment for me because of the enchanting geisha who modeled it.” Playful, perhaps, but a bit cruel.

His letters bear the marks of his long literary education, acquired primarily in his parents’ extensive library and his mother’s bohemian salons. Guevara was an avid reader from an early age, devouring Baudelaire, Verlaine, Mallarmé, and Zola in French, along with Freud, Marx, Faulkner, and Steinbeck — all before he was 18. He recited poems by Pablo Neruda, a lifelong favorite, to woo girls. Later, he read Camus, Kafka, Sartre, Machado, García Lorca, Whitman, and Frost, and he wrote poetry himself throughout his life. Letters from his Havana office to writers such as Ernesto Sábato are filled with admiration, and even his idealistic 1965 farewell to his parents, as he headed off for further military adventures, name-checks the horse of Don Quixote: “Once again,” he writes, “I feel the ribs of Rocinante beneath my heels…”

“Che is fairly intellectual for a Latino,” admits a declassified CIA report from 1958. Indeed.

¤

LARB Contributor

Joy Castro is the award-winning author of One Brilliant Flame (2023), a historical suspense novel about 19th-century Cuban insurgents in Key West; Flight Risk (2021), a finalist for a 2022 International Thriller Award; the post-Katrina New Orleans literary thrillers Hell or High Water (2012), which received the Nebraska Book Award, and Nearer Home (2013), which have been published in France by Gallimard’s historic Série Noire; the story collection How Winter Began (2015); the memoir The Truth Book (2012); and the essay collection Island of Bones (2012), which received the International Latino Book Award. She is the series editor of the Machete series in literary nonfiction at The Ohio State University Press and edited the anthology Family Trouble: Memoirists on the Hazards and Rewards of Revealing Family (2013). She is currently the Willa Cather Professor of English and ethnic studies at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, where she directs the Institute for Ethnic Studies.

LARB Staff Recommendations

One Fell Swoop: On Joy Castro’s “Flight Risk”

Desirée Zamorano reviews Joy Castro’s “Flight Risk,” a novel about a successful high-society woman’s complicated relationship with her hidden West...

“We Need Wholesale Decolonization”: A Conversation with Grieve Chelwa

An African economist explains why mainstream economics is a colonialist enterprise.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!