Kim Newman’s Dazzling Genre Multiverse

Rob Latham reviews the latest novel in Kim Newman’s “Anno Dracula” series.

By Rob LathamMarch 9, 2020

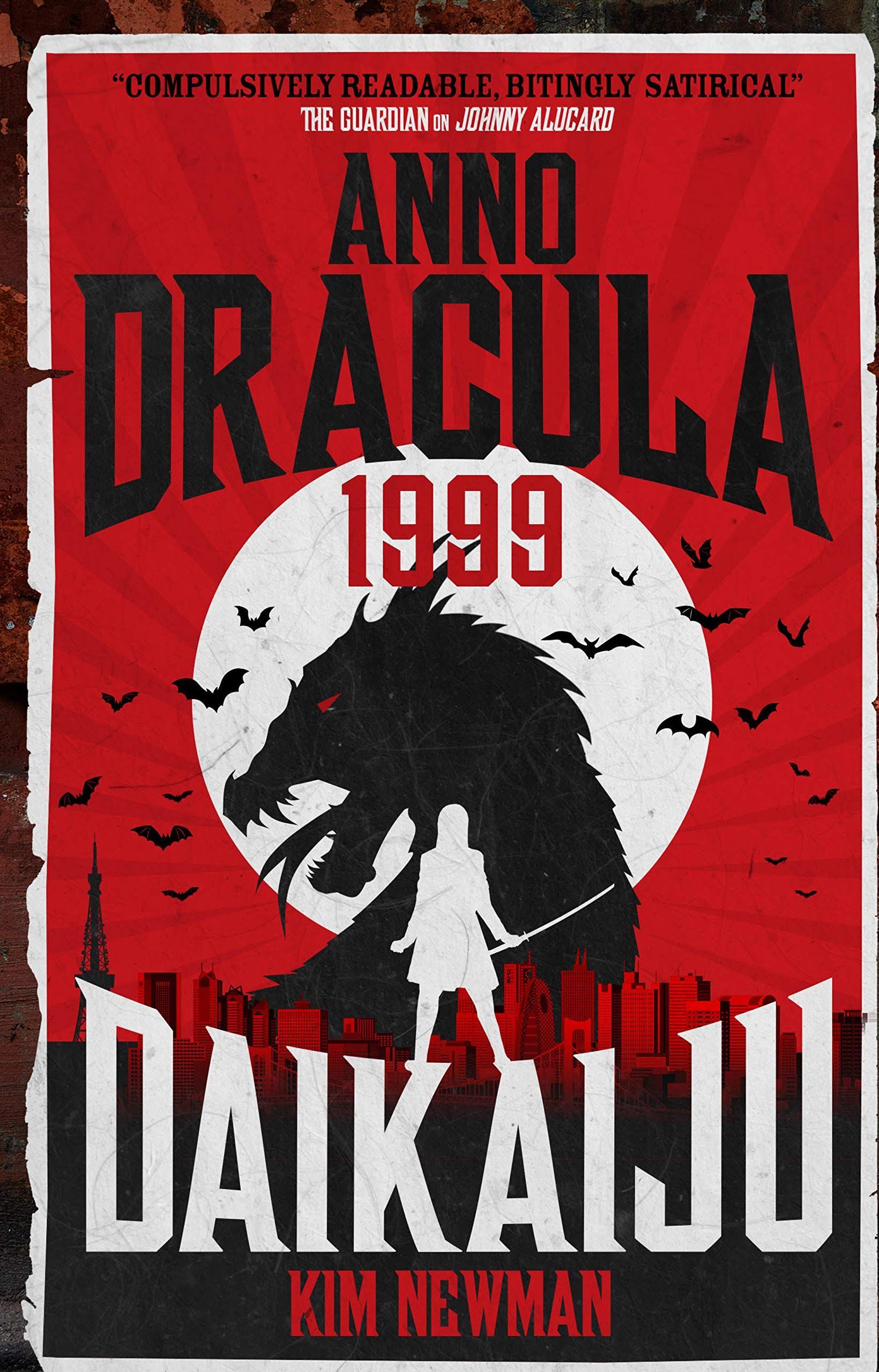

Anno Dracula 1999 by Kim Newman. Titan Books. 400 pages.

BRITISH AUTHOR KIM NEWMAN’S “Anno Dracula” series — the smartest recasting of the vampire mythos, and one of the tastiest pop-cultural confections, of the past three decades — has had a complicated evolution. The author’s basic concept — that the events narrated in Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel actually occurred, save that Dracula, rather than being bested by Van Helsing and crew, triumphed over his adversaries, married Queen Victoria, and became ruler of England and the Empire — was developed by Newman, in collaboration with his friend Neil Gaiman, during the mid-1980s, its first crystallization in print being the novella “Red Reign” in Stephen Jones’s 1992 anthology The Mammoth Book of Vampires. Later that same year, an expanded version was published, as Anno-Dracula, by Simon & Schuster in the United Kingdom and, the following year, by Carroll & Graf in the United States (the errant hyphen was discarded in subsequent editions), and the novel went on to be nominated for the World Fantasy Award and to win the International Horror Guild Award. Critics were delighted with Newman’s richly imagined alternative history, in which humans coexist uneasily with a vampire elite, whose immortality they envy and whose powers they fear.

Three years later, a sequel, The Bloody Red Baron (1995), came out from the same two publishers, with the US edition this time preceding the British, but things started to get tricky with the third installment: Carroll & Graf, when it released the novel in 1998, changed Newman’s preferred title from Dracula Cha Cha Cha to Judgment of Tears: Anno Dracula 1959, with Newman restoring his original moniker for the British edition, published in 2000. Despite this confusion of names, the series seemed to have gelled into a cohesive trilogy, the first volume culminating with Dracula’s violent expulsion from the British throne, the second seeing him lead the German war machine during World War I, and the third chronicling his decadence and death in Italian exile in the 1950s. But the author kept the basic setup alive — sans Dracula — in a series of novellas published in various venues during the late 1990s and early 2000s, which he eventually gathered, along with newly written interstitial material, into an episodic fourth book, set principally in the United States during the 1970s and ’80s, called Johnny Alucard (2013).

This volume saw the series move to a new British publisher, Titan Books, who also brought the first three novels back into print in uniform editions chockfull of extra features supplied by the author: afterwords and annotations, excerpts from abortive film treatments, and whole new freestanding story sections. Since Titan titles were (and are) distributed in the United States, readers on both sides of the Atlantic could finally access, between four sets of affordable covers, Newman’s complete, wildly ambitious vision of a divergent 20th century dominated by vampires and their human enemies, collaborators, groupies, and slaves. That the new publisher was willing to devote so much energy and resources to the project might have seemed surprising given that Titan is mostly known for comics and graphic novels, media and gaming tie-ins, and coffee-table books on art and animation, but then Newman’s “Anno Dracula” series is one of the most media-literate, rampantly intertextual, exuberantly allusive compendiums of pop-cultural materials ever assembled.

A contributing editor to Sight & Sound and a longtime columnist for Empire magazine, Newman is himself a media critic of some note, with a magisterial command of popular genres, ranging from horror (see his Nightmare Movies [2011]) and science fiction (see Apocalypse Movies [1999]) to Westerns (see Wild West Movies [1990]) and film noir (see his extensive contributions to The BFI Companion to Crime [1998], edited by Phil Hardy). (Titan recently released a gathering of Newman’s Empire columns, as Video Dungeon [2017].) He has also written, under the pseudonym Jack Yeovil, a number of books set in the “Warhammer” gaming universe, which prominently feature a character who is a major player in the “Anno Dracula” series as well. Newman’s first novel under his own byline, The Night Mayor (1989), was a cyberpunkish tale set largely in a virtual-reality domain stitched through with subplots and peopled by characters pilfered from a wide range of noir films, both celebrated and obscure (Wilmer the Gunsel, from The Maltese Falcon [1941], shows up driving a taxi, while scenes from Scarlet Street [1945] and The Big Heat [1953] are spontaneously reenacted). Like David Thomson’s 1985 novel Suspects, The Night Mayor is both a knowing homage to and a waggish send-up of hardboiled clichés, of “an all-night eternity: a world for cops, hoodlums, showgirls, barflies, night-call nurses, vagrants, vampires and cab drivers,” where it was “always two thirty in the morning and raining.”

Given this background, it is hardly surprising that Newman’s favored form is the pastiche, the ironic recycling of well-established motifs and materials. His densely textured layers of allusion are at once deeply nostalgic and ruthlessly satirical: his impulse is not merely to borrow but to subvert. The pleasure of reading the “Anno Dracula” series lies both in its critical interrogation of the patriarchal and imperialist dynamics of classic vampire stories and in the sheer profusion of loving detail with which Newman evokes this hallowed tradition. Each of the novels is ingeniously built up out of a corpus of pilfered images, characters, and plot strands appropriate to its historical setting; for example, the first book, set in late-Victorian England, borrows from Stoker, John Polidori, Sheridan Le Fanu, E. F. Benson, and their filmic legacy, with sprinkles of Sherlock Holmes and Fu Manchu thrown in for spice. The cleverest cluster of references occurs in Dracula Cha Cha Cha, with its plot a hybrid of ’50s “while in Rome” melodramas like Three Coins in the Fountain (1954) and ’60s gialli by Mario Bava and Dario Argento, and its dramatis personae an assemblage of languid Eurotrash out of La Dolce Vita (1960) by way of Bloody Pit of Horror (1965) — complete with a vampire James Bond!

Newman further complicates these scenarios by weaving in actual historical personages — some vampire, some “warm” (his term for mere humans); for instance, in the second novel, celebrated fighter ace Baron von Richthofen is transformed into a shapeshifting monster, while the ghastly pallor and zombified demeanor of Andy Warhol is explained, in Johnny Alucard, by the fact that the artist is literally undead. Meanwhile, characters filter in from other Newman series, in particular his cunning tales of the “Diogenes Club,” a supernatural version of the British secret service, which combine the stodgy ratiocination of Arthur Conan Doyle (the club was founded by Sherlock’s polymath brother, Mycroft) with the psychedelic whimsy of The Avengers (1961–’69). In other words, the “Anno Dracula” books are heady, sinuous stews of reference and cross-reference — citations that Titan’s editions make easier to decode thanks to the author’s helpful annotations (though do keep your smartphone handy: virtually every character or place name forks out into some cryptic pop-cultural context, not all of which Newman glosses).

All of this might make the novels sound rather exhausting to read, and to some extent they are. When, in the third volume, Patricia Highsmith’s sociopathic slacker Tom Ripley is framed for murdering Dracula by Argento’s Mater Lachrymarum, a witchlike being (from the director’s 1980 movie Inferno) who manifests in the text as a kaleidoscopic array of avatars out of classic films by Fellini, Buñuel, and Pasolini, the reader can be excused for experiencing a bit of narrative whiplash. Frankly, you either like this sort of thing or you don’t. From my perspective, it’s hard to see how vampire stories can be written any other way: the tradition is by now so encrusted with rust and routine that it takes a shrewd eye for reappropriation and recontextualization to make its time-weathered tropes speak afresh. And Newman definitely has a shrewd eye; indeed, he is among the most skillful pasticheurs ever to turn his gaze to popular media, on par with the late Philip José Farmer, whose “Wold Newton” series constructs an elaborate genealogy linking most major — and many minor — characters from 19th- and 20th-century popular culture (e.g., Tarzan, Phileas Fogg, Allan Quatermain, Doc Savage) and which exerted, as Newman has acknowledged, a significant influence on the development of the “Anno Dracula” multiverse.

What makes Newman’s series so compelling, however, is not just its lavish collage of vampire lore and the moments of delighted recognition this assemblage affords the discerning reader. Even if one is oblivious to most of their canny borrowings, the books provide substantial readerly pleasures. For one thing, Newman’s plots are suspenseful and absorbing: The Bloody Red Baron, for instance, is a thrilling war story, filled with vivid aerial dogfights and gruesome scenes in the trenches, yet we are also privy to the councils of the Great Power rivals, with undead prime ministers and field marshals scheming to make the same stupid blunders their warm counterparts did in the history we know (in Newman’s treatment, the pitiless maw of battle swallows vampires as readily as human prey). Despite their length, the first three books are quick, captivating reads, propelled by deft cross-cutting between scenes and the author’s witty, sophisticated tone.

The series’s most remarkable accomplishment, given its magpie structure, is that the main characters emerge as more than mere pasteboard parodies. This is especially true of the three figures Newman has invented more or less out of whole cloth: Charles Beauregard, an urbane agent of the Diogenes Club who, although rather too fond of callous realpolitik, is a wise and genuinely warm person (in both senses of the term: despite being given numerous opportunities to “turn,” he resolutely rejects the lure); Geneviève Dieudonné, Charles’s undead lover, a 500-year-old “elder” who never loses her empathetic bond with humankind — and who, thanks to her robust repertoire of vampiric powers, figures in several spectacular set-pieces as a kick-ass action heroine; and, above all, Kate Reed, a character Stoker originally created for his novel but dropped, whom Newman refigures into a hesitantly feminist, staunchly socialist vampire whose occupation as a freelance journalist takes her to some of the most infamous scenes of 20th-century history. Firm enemies of the despotic Dracula, this trio emerges, over the course of the first three novels, as a complicated coalition — at times, almost a ménage à trois — struggling to forge a world where humans and vampires can attain some kind of halting but hopeful affinity. Newman handles this thematic crux with real emotional gravity, even amid all the playful citations.

But the long-lived Charles, like his undead nemesis, finally dies in Dracula Cha Cha Cha, and Kate and Geneviève go their separate ways, and so it appeared that the series, aside from a few scattered spin-offs, had pretty much concluded. Johnny Alucard, despite being the longest book yet, did little to alter this assessment, coming across — due in no small part to its piecemeal construction — as a series of pendants and sidelights to the main attraction, rather than a serious effort to strike out on new paths. While it does bring back Kate and Geneviève, who find themselves embroiled in a sketchy plot by the eponymous vampire — an erstwhile war orphan “turned” by Dracula who rises from obscurity to become a Hollywood mover and shaker — to revive his Dark Father from the dead, it is rather hard to take this scheme seriously given the book’s tone, which is much goofier and more over-the-top than in the earlier volumes.

The story’s central appeal is that it shifts the action to North America, an offstage presence in the first three books, largely because vampirism never really gained a foothold on the continent. Readers thus had the opportunity, for the first time, to see Newman work his parodic alchemy on New World texts and institutions. Unfortunately, perhaps because of this move to American shores, the author’s satire became considerably broader and, well, dumber. Most of the jokes come at the expense of the movie industry, which — given his background as a film critic — Newman knows quite well; but the result is a predictable exercise in bitchy dirt-dishing familiar from classic send-ups like Robert Altman’s 1992 film The Player (prominently cited here). There are too-cute references to fictional ventures like “the long-in-development Anne Rice project, Interview with the Mummy, which Elaine May was supposed to be making with Cher and Ryan O’Neal,” and standard sardonic commentary on the lowly status of writers in Hollywood — although Newman’s depiction of the harried “Jack Martin” (a stand-in for horror author Dennis Etchison, who used that pseudonym on his film novelizations), compelled to script cheesy porn scenarios like Debbie Does Dracula to make ends meet, draws a few laughs, as do cameo appearances by a host of vintage film and TV characters: Lt. Columbo investigating killings by a vampire-slaying teenage girl, Moondoggie and “The Dude” hanging out with Geneviève at her Jim Rockford–style trailer in Malibu, and so on.

The cleverest sections involve ill-fated adaptations of Dracula, worked out in elaborate detail, from Francis Ford Coppola’s muscular version, shot on location in Romania — basically, an alternative-historical Apocalypse Now (1979), with Martin Sheen as Jonathan Harker and Brando as the Count — to a metafictional rendition by Orson Welles, a kooky spoof of the director’s botched final film (posthumously released in 2018 as The Other Side of the Wind), with a lengthy tracking shot through the Borgo Pass that exceeds in complexity the famous opening to Touch of Evil (1958). But these nicely conceived set-pieces tend to get lost amid tepid lampoons of SoCal inanity, complete with a celebrity-vampire religion called the Church of Immortology and a filmmaker’s mansion known as “Castle Dracula 90210.” Like the previous three novels, Johnny Alucard is a quick and (mostly) engaging read, but it is blatant where those books were subtle, silly where they were droll. (It also scrambles the logic of the series’s overarching title, “Anno Dracula,” since — unlike the previous volumes — its action is not set during a single pivotal year but sprawls across the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s.)

One Thousand Monsters (2017), the first real novel in the series in two decades, marked both a welcome return to form and a significant shift in emphasis. It came on the heels of a comic-book treatment, Anno Dracula 1895: Seven Days in Mayhem (2017), also published by Titan, which revisited the later days of Dracula’s reign in England, with Kate joining a secret society plotting a coup against the king vampire. The first adaptation of the series for visual media, Seven Days in Mayhem is a splendidly gory romp, handsomely illustrated by Paul McCaffrey, that recaptures some of the piquant steampunk flavor of the early books. It also introduces a character who would become a major figure in the new novel: Christina Light, a.k.a. the Princess Casamassima, an anarchist aristocrat (and fugitive from Henry James) who champions the violent overthrow of the tyrant Dracula. Her scheme foiled in the comic, the Princess — along with dozens of other political prisoners, including Geneviève — is crammed onto an ancient freighter and exiled from England. After many scrapes at sea, including feuds with a brutal captain out of Jack London’s The Sea-Wolf (1904), the outcasts find an uneasy refuge in Meiji-era Japan, and their subsequent adventures in that fraught country — torn between senescent tradition and a burgeoning modernity — form the core of One Thousand Monsters.

Fretful over the ascendency of Dracula and his minions in the West, the Japanese emperor, in a prophylactic move, has built a huge enclosed ghetto to house both undead immigrants like the princess and her crew and the nation’s own native monsters (or yōkai). This settlement is brutally policed by conscripts of the Black Ocean Society, an ultra-nationalist paramilitary group, spearheaded by Lieutenant Majin, who is also a secret agent of Taira no Masakado, a diabolical samurai spirit who causes earthquakes and plagues. The imprisoned yōkai, meanwhile, have their own hierarchy, ranging from the lowly tengu and nappa (bird and turtle demons) up to the “Woman of the Snow,” Yuki-Onna, a “vampire empress” whom Princess Casamassima awakens from frozen sleep to combat Majin. In Bloody Red Baron, Newman displayed his mastery of battle sequences, but he outdoes himself here: armies vampire and warm clash wildly in a landscape altered moment to moment by tremors and blizzards, in scenes bristling with dreamlike horrors, from a lumbering steam-driven golem to whirling clouds of razor-toothed butterflies. Amid this epic struggle, a Westernized vampire known as Dorakuraya (the Japanese pronunciation of Dracula) schemes to harness the powers of Yuki-Onna for his own imperialist ends.

In depicting the motley yōkai, Newman scours the vast bestiary of Japanese folklore, including the mutant versions popularized in the West by Lafcadio Hearn (who makes a cameo appearance toward the end of the story), as well as local treatments like Kineto Shinda’s 1964 film Onibaba. With his typical magisterial brio, the author marshals a wide array of cultural resources to evoke a fantasy vision of Japan hovering on the brink of modernity. Historical films about the country, both native (e.g., Kurosawa’s Sanjuro [1962]) and Western (e.g., Scorsese’s Silence [2016]), provide characters and plot strands, while striking images are lifted from the ample arsenal of contemporary manga and anime: there is a grotesque hentai sequence set in an opulent cathouse (the shapeshifted girls are literally feline — bakeneko, or cat demons), and several scenes feature a creepy trickster child, Tsunako, from the “Shiki” graphic novel series, who controls a “puppet ninja theater” of maniacal dolls.

Interleaved with the chapters set in Japan are passages from Geneviève’s journal, in which we learn more about her life prior to the accession of Dracula, especially her years spent in Paris during the Belle Époque — passages that give Newman license to display his deep knowledge of French popular culture, including Louis Feuillade’s silent serial Les Vampires (1915) and the proto-pulp novels of Paul Féval and Gaston Leroux. Buttressing this armature of Franco-Japanese allusions is a dizzying hodgepodge of citations to global fantastic cinema, from the British Gothic shocker The Blood Beast Terror (1967) to the low-budget Spanish gorefest La llamada del vampiro (1972) to the German porn comedy Love, Vampire Style (1970). Because this volume doesn’t feature annotations, readers have to ferret out these references on their own, but Newman’s story is so engrossing that one can simply let the jazzy shadowplay of his pastiche flicker fitfully in the background. In any case, this novel confidently recaptures the dazzling imaginative energy of the first three books.

The latest installment, Anno Dracula 1999: Daikaju, published by Titan last October, takes up again — exactly one century later — the setup developed in the previous book. At the end of One Thousand Monsters, the emperor converts the undead ghetto into an independent district — a “vampire bund” — with a 100-year lease assuring its autonomy, under the stewardship of Princess Casamassima, an arrangement that seeks to preserve a cordon sanitaire against the spread of vampirism in the country (this plot twist nods to Nozomu Tamaki’s popular manga, Dance in the Vampire Bund). Meanwhile, Taira no Masakado, though stoutly defeated, has been prophesied to return in the form of a “giant dragon” — and if that makes readers think of the fire-breathing, city-stomping Gōjira, it’s supposed to. Indeed, daikaju is a term, literally meaning “strange beast” (or, as Newman has it, “Bloody Huge Fucking Monster”), that film buffs use to refer to the midcentury craze for “creature features” of the Godzilla variety, and the new book contains a wealth of citations to the horde of freakish fiends atom-age Japan has unleashed upon the world.

Newman cleverly keeps the really big-name monsters offstage until the very end, when he mounts a thrilling “robosaur” battle that Ishirō Honda would have envied, opting instead for an encyclopedic deployment of allusions to the smaller-scale, though no less prominent, brutes and villains that have dominated Japanese popular culture in the postwar period: ninja, yakuza, ronin, “drift” racers. Alongside the expected citations to techno-horror and “mad science” movies — from Goke, Body Snatcher from Hell (1968) and Horrors of Malformed Men (1969) to Ringu (1998) and Infection (2004) — Newman also foregrounds the heist story, the “gun-fu” shoot-’em-up, and other modern crime genres: noir-ish cops and crooks out of Takashi Miike’s Ichi the Killer (2001) and Shinya Tsukamoto’s Nightmare Detective (2006) rub shoulders with shapeshifting demons culled from Honda’s The Human Vapor (1960) and the 1970s manga Wolf Guy, among myriad other sources. The result is a weird, edgy vision of hyper-modern Tokyo that contrasts neatly with the stately elegance of the Meiji era depicted in the previous volume.

Newman’s most substantial borrowings are from a Western genre that has notably — and vividly — sought to capture the neon sheen of contemporary Japan: cyberpunk. This legacy is signaled in the novel’s first line, which echoes the famous opening of William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984): “The sky above the city was the colour of arterial blood splashed across a shower curtain.” Despite being set in our historical past (all the action takes place on New Year’s Eve, 1999), Daikaiju is, in effect, a 20-minutes-into-the-future sci-fi romp replete with a powerful zaibatsu (the global megacorp Light Industries, which Princess Casimassima now runs), a murderous doomsday cult (Aum Shinrikyo hybridized with the “New Flesh” of David Cronenberg’s Videodrome [1983]), and a posthumanist fantasy of transcendent virtuality (the prophesied “Ascension,” a mysterious singularity in which the Princess will be radically transformed). As in classic cyberpunk stories, Daikaiju prominently features an “outlaw hacker,” Jun Zero, whose wetware prosthesis — a glass hand, pilfered from a Harlan Ellison Outer Limits episode — functions like a nifty cross between a virtual assistant and a digital lockpick. Like Neuromancer, much of the story involves a shadowy cyber-caper that brings together a variegated crew of outcasts and oddballs, with lines of alliance and rivalry shifting abruptly, sometimes from chapter to chapter.

It’s impossible to describe the novel’s plot in any detail without spoiling the big reveals Newman has strategically laced throughout, but suffice to say that the main event is the expiration, on the first day of the new millennium, of the lease segregating the vampire bund from the rest of Japan, and the main business involves how various factions — the Princess and her yōkai, the cult and its minions, Jun Zero and his cryptic affiliates, the agents of the Diogenes Club and other Western meddlers — seek to exploit or profit from this event. This is Newman’s most infernally complicated story, briskly cross-cutting among several dovetailing subplots as the clock ticks down to midnight and the onset of the Ascension. Always adept at crafting striking set-pieces, of which Daikaju has its share (including the final furious scenes of skirmishing mecha), the author has also become a true master of suspense, ending nearly every chapter with a breathless cliffhanger, as the action shifts to another venue. It does get a bit hectic at times, but the payoff is deeply satisfying, wrapping up plot strands that stretch, in some cases, well back into the earlier volumes.

Indeed, as “Anno Dracula” has developed, Newman has drawn significant links not only across this specific sequence of books but also among his numerous other series, gradually generating a tangled maze of cross-reference on a par with the intricate SF multiverse of Michael Moorcock (an acknowledged influence). One major thread of Daikaiju’s plot involves the enigmatic origins of Richard Jeperson, the dapper head of the Diogenes Club, and his vampire sidekick-cum-bodyguard, Nezumi — who, we discover, is an alumnus of Drearcliff Grange, an occult girls school, the exploits of whose denizens Newman has chronicled in other novels and stories. The coda to Daikaiju, which shifts scenes to a perilous New Year’s Eve party in Los Angeles attended by Kate and Geneviève, adumbrates additional hookups with a French offshoot of the Diogenes Club featured in Newman’s sumptuous 2016 novel Angels of Music.

One consequence of this escalating pattern of self-reflexivity is that readers new to the author might be too bewildered to know precisely where to begin. Those looking to dip a toe into these sparkling, if turbulent waters should probably start with one of Newman’s story collections, such as The Original Dr. Shade (1994) or Famous Monsters (1995) or The Man from the Diogenes Club (2006), which give a good sense of the author’s ludic imagination and the widescreen scope of his pop-cultural pastiche. Some may find the overall effect too vertiginous and hermetic, and it must be admitted that, at times, Newman’s work can seem mere ventriloquy, an arch burlesque of timeworn elements, however expertly assembled. But that is the danger any parodist runs, and at its best, his fiction includes some of the wittiest and most ambitious parodies in the contemporary canon.

The author’s restless genre-switching and frenetic allusiveness bespeak an admirable unwillingness to settle down as a creative talent — lest, perhaps, the conventions of fixed genres gel and harden around him. For all his adroit scrounging in the archives of formula fiction, there is nothing formulaic about Newman’s own work: it is grand and exquisitely strange, urbane yet quite hilarious. It repays both erudite consumers alert to the subtlest citations, from the highbrow (Swinburne, Nabokov) to the lowest of the low (Ninja III: The Domination [1984]), and also ordinary readers hankering for a dandy adventure story. At 60 years old, with a four-decade career behind him, Kim Newman continues, intrepidly, to evolve; while looking forward to his fresh mutations, we can be grateful for the many rich, scintillant, ingenious mindscapes he has thus far staked out and explored.

¤

LARB Contributor

Rob Latham is the author of Consuming Youth: Vampires, Cyborgs, and the Culture of Consumption (Chicago, 2002), co-editor of the Wesleyan Anthology of Science Fiction (2010), and editor of The Oxford Handbook of Science Fiction (2014) and Science Fiction Criticism: An Anthology of Essential Writings (2017).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Exhuming Lafcadio Hearn

Jeff Kingston looks at three new books by and on the extraordinary Lafcadio Hearn.

Magic Carpet Rides: Rock Music and the Fantastic

The long and complex relationship between fantastic fiction and rock music.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!