Kalokohan!: On Martika Ramirez Escobar’s “Leonor Will Never Die”

Katarina O’Briain reviews Martika Ramirez Escobar’s “Leonor Will Never Die.”

By Katarina O’BriainMarch 6, 2023

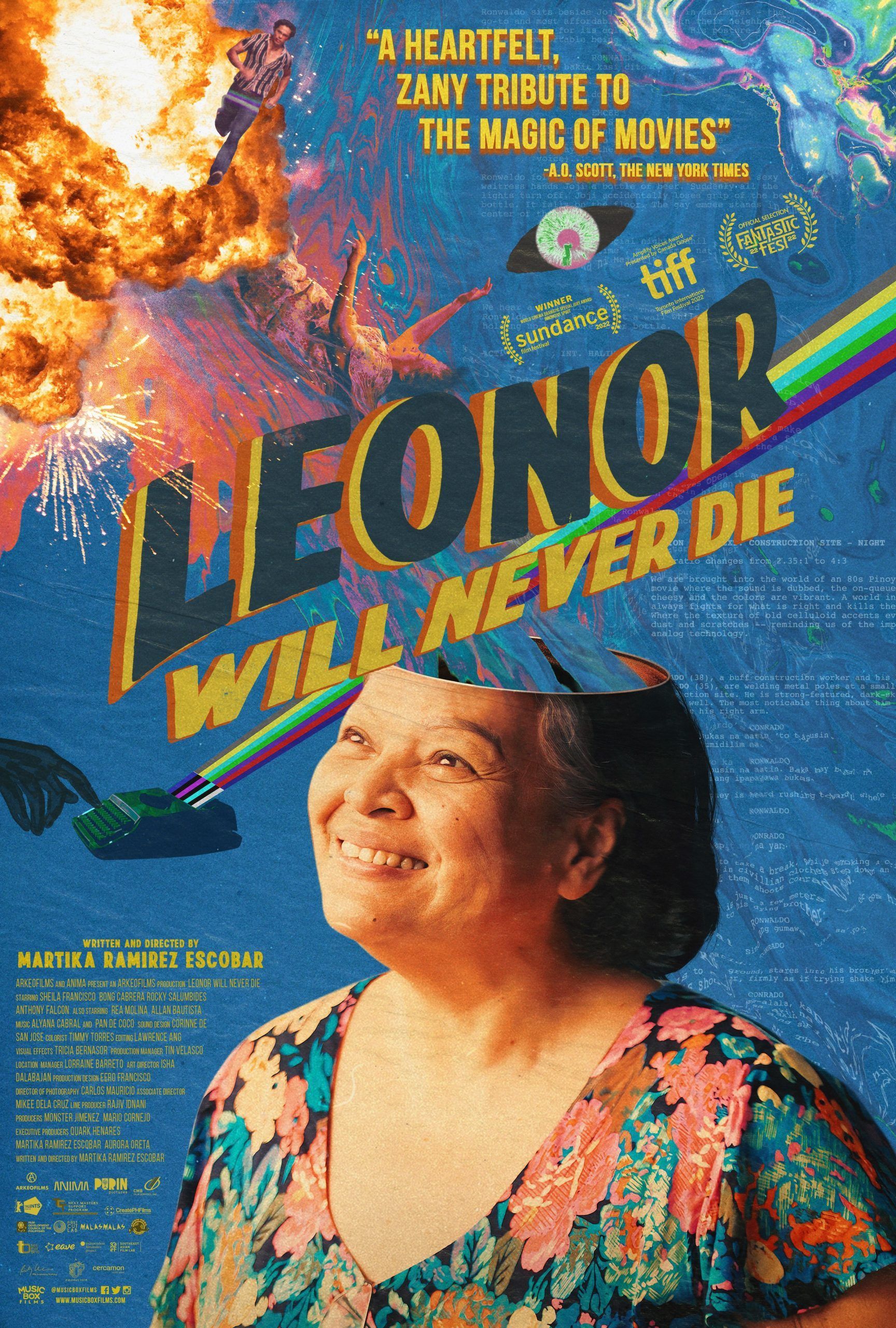

MARTIKA RAMIREZ ESCOBAR’S Leonor Will Never Die begins with a yell from behind the opening production credits: “Kalokohan!” (“This is absurd!”) The credits soon disappear to reveal a dinged-up television playing an action movie in Leonor’s bedroom as she pushes a large chest into its center to change a ceiling light bulb. It’s easy to miss the first time around, but the yell has come from Leonor, a former action screenwriter, cutting across multiple layers of reality, from her own film yet to be made.

The beginning of Leonor tracks something like everyday life. Leonor Reyes (Sheila Francisco) used to play a major role in the world of action cinema, but that was a long time ago. Now more of a lola (grandmother) figure, spending most of her time at home in her duster housedress, she forgets to pay the electricity bill, to the immense frustration of her adult son Rudie (Bong Cabrera), who is trying to secure his visa to move away. But after an accident with a television set sends Leonor into a coma and launches her into her unfinished screenplay, the film moves freely across its kaleidoscopic settings: from a vaguely contemporary Manila (circa 2008) to the world of 1970s-era action cinema to a universe where Escobar herself works to finish Leonor’s project, one more ambitious and defiant than the genre would seem to allow.

Action movies reached their height in the Philippines after Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law in 1972. At a time when, as Escobar describes it, “Filipinos felt the most helpless,” the action formula provided comfort. In subsequent decades, action star Joseph Estrada became president, then mayor of Manila, and even Leonor’s favorite actor, Fernando Poe Jr. (FPJ), narrowly lost the presidential election in 2004. Known commonly as “Erap” (meaning pare or friend) and “Da King” respectively, these action-stars-turned-politicians promised both familiarity and superhuman agency: a form of authoritarian political appeal that continues to hold sway. As Escobar said after winning the Innovative Spirit Award at Sundance last year, several months before the presidential election would see another Marcos return to power, “The Philippines is about to enter the third act of a bad action movie.”

Leonor holds a surprisingly prominent place in this masculinist lineage. The technician from Manila Electric delays cutting off the power because his mother loves Leonor’s movies. Leonor happens to share a last name with FPJ’s alternate pseudonym, Ronwaldo Reyes; she may have named both her other son Ronwaldo—who has died but still visits his family as a semitransparent ghost—and the hero of her screenplay after him. Leonor’s ex-husband, Valentin, is a former movie star now running for barangay captain, the leader of a regional council. As he tells someone trying to sell him the television that will later land Leonor in her own movie: “I don’t watch much television anymore because I’m watching over all of you.” The comforting language of paternalistic authority slides easily into structures of discipline and state surveillance here and in many other moments of the film.

Escobar spent several years working on the details of her film-within-a-film, carefully balancing the grain and damage to mimic the effect of action movies that are initially shot on film, transferred to video and television, then played again in theaters or on YouTube. This aesthetic of remediation feels appropriate for a genre that gets painfully repeated both on and offscreen. Even more than in its reproduction of the stylized violence of ’70s-era Pinoy action movies, Leonor represents the continued power of that moment through its insistent repetitions. Lines, images, songs, and scenes echo and reverberate across its layers of reality, suggesting that political life in the Philippines has become a bad action movie that may never end.

In this respect, Escobar echoes Anocha Suwichakornpong’s By the Time It Gets Dark (2016), exploring the tense relationship between cinema and history—but from a different angle. Suwichakornpong has described her own work as an “attempt to deal with the impossibility of making a historical film in the place where there is no history,” and her film indeed insists on the failure to make the past present through that medium. Early on, a director is seen yelling at her actors to “be more brutal” in their reenactment of the 1976 Thammasat University massacre. The awkward use of the imperative mood strains against the historical trauma that she seeks, impossibly, to reproduce. Throughout By the Time It Gets Dark, windows, frames, and screens proliferate as visual reminders of a medium that occludes and reflects more than it recovers.

Escobar’s film is similarly filled with screens and reflections, but the artificiality takes the form of a spectacle that reaches out into everyday life. When Leonor furiously types out her script, while banging an umbrella against her desk, she offers an intimate portrayal of everyday life that’s been saturated by action cinema. When she tells Isabella, her film’s imperiled heroine, that they are entering “another fight scene” and proceeds to recite the characters’ lines in rapid simultaneity, Leonor offers a comedic demonstration of her expertise in a genre that’s defined by repetition. In the process, she gestures toward the absurd predictability of a state politics that seems to keep the same rhythms as that popular cinematic mode.

In her insistent blending of cinema and reality—demonstrating the ways in which they are already irrevocably blended—Escobar reinforces the truth behind Jordan Peele’s half-joking claim that Get Out (2017) is a documentary. She also demonstrates how that statement begins to feel redundant, repetitive, across global histories. She tracks the continuity of the world of Kidlat Tahimik’s Why Is Yellow the Middle of the Rainbow? (1994), in which Tahimik’s son (wearing an Apocalypse Now T-shirt) confuses a newspaper image of the Mendiola massacre of January 1987 for the most recent “Rambo film.”

¤

Escobar introduces her film-within-a-film with an eye to these intertwined histories of political and cinematic violence. Having just learned of a local film contest, Leonor decides to return to one of her unfinished screenplays. She holds the pages in her hand and looks up with a pained expression as soft sounds of typewriting become increasingly louder. The aspect ratio shrinks to 4:3, revealing a grainy blue sky. Superimposed are the words of Leonor’s title, Ang Pagbabalik ng Kwago (The Return of the Owl), introduced with the echoing blasts of gunshots. A series of shots from behind a camera’s crosshairs follow Ronwaldo as he carries a bundle of metal piping toward a scrapyard, balanced on one shoulder as though it were a bazooka. In Kwago, instruments of labor often double as weapons.

Film, as Paul Nadal suggested in an interview with Gina Apostol about her novel Insurrecto (2018), shares a history with the gun in the Philippine context, both inventions refined during the revolutionary period as “technologies of American empire.” Tracking the development of the stereoscope, an early technology of film, and the Colt .45, which was “invented to kill the Filipino juramentados, violent insurgents out of their minds, during the Philippine-American War,” Apostol’s book explores how both technologies become ways of manufacturing and violently reinforcing what counts as reality.

Leonor Will Never Die takes up these histories, but with coordinates to a much later context. We are introduced to the villains of Kwago through the vulgar Taglish of Rodrigo Duterte: “Son of a bitch! Fucking bird, fuck!” Ricardo (Ryan Eigenmann) yells as he tries to shoot a bird out of the sky. Standing next to him, the Mayor (Dido Dela Paz) laughs, says in English, “Let me show you how it’s done,” and uses a handgun to shoot the bird mid-flight. Toward the end of Kwago, the Mayor commands Isabella (Rea Molina), Ronwaldo’s love interest, to knock down a stack of cement blocks holding up Ronwaldo, who is tied up and suspended on a noose. He laughs and repeats with glee, “Pumokpok!”—a Cebuano word meaning “to beat up.” The onomatopoeia echoes the sound of Duterte’s Oplan Tokhang: as Apostol puts it in Insurrecto, the “drug-war world of tokhang: toktok-hangyo: knock-knock, plead-plead.” In Escobar’s film and elsewhere, the violence of Duterte’s genocidal drug war seems to erase the line between reality and fiction—between reality and what shouldn’t be possible.

In a recent essay entitled “Duterte’s Phallus: On the Aesthetics of Authoritarian Vulgarity,” Vicente Rafael tracks Duterte’s rhetoric as an example of Achille Mbembe’s concept of “intimate tyranny,” which, in the context of the postcolony, “links the rulers with the ruled.” Such obscenities and vulgar masculinist language fit easily into the politics of action cinema: about halfway through Kwago, part of the Mayor’s gang shows up at Ronwaldo’s construction site, and when Ronwaldo refuses to say where Isabella is, one of them asks, “You think you’re hard?” The sequence ends with Ronwaldo staring down coldly as he pours cement over the two screaming men and says, “Who’s the hardest one now?” The question returns yet again in a later scene as Ricardo points a gun at Ronwaldo’s head and yells, “Let’s see whose hard-on is harder!”

Against this language of hardness and hard-ons, Leonor cries out for the opposite. The film itself is filled with images of softness. After being hit in the head with the television set, Leonor appears to fall endlessly against a sky-colored background for a few seconds that recall the fluid movement of Peele’s “Sunken Place”; she then lands on an old mattress in a back alley of her own film’s diegesis. Tearing a strip of fabric from one of several laundry lines that make up the composition of the scene, Leonor ties it, Rambo-like, around her head to cover up her recent headwound. A moment later, we see her smiling with mild surprise, but mostly warmth and affection, as she finds herself in the audience of a dramatic arm-wrestling match from which Ronwaldo emerges victorious. Moving through Kwago in her shapeless floral duster, Leonor offers a visual sign of something that resists the rigid structures of her most beloved genre.

At several moments, the women in the film attempt to halt the perpetual repetition machine of action cinema. At the beginning of Leonor and toward the climactic end of Kwago, Leonor’s “Kalokohan!” cries out against these continued histories of action and state violence. Early glimpses of Leonor’s script center Isabella’s language of refusal: “Ayoko [I don’t want it],” and then, “I will never listen to you! I am not your puppy!” When we first meet Isabella, she is performing at a nightclub, adorned in yellow flowers while singing Leonor’s favorite song, which plays in a different layer of reality at the beginning of the film. Both wear soft fabrics with yellow flowers on them, an aesthetic contrasting the stylized violence of the film-in-a-film and reminding the viewer of the color of the 1986 People Power Revolution, a moment in history that sought to resist the banal repetitions of authoritarian violence.

These moments of softness are held against a sharp background of expected bloodshed. For most of the film, the audience might well assume that the ghost of Leonor’s son, who moves in and out of the lives of his loved ones with a visible bullet wound in his chest, is, like Ronwaldo’s brother in Kwago, one of the many victims of a genocidal drug war. But when Leonor apologizes to Ronwaldo’s mother for making her feel the same loss, she explains that her son died as a child on set when a prop gun turned out to be real. “It was like a film,” she says, her eyes shimmering against the scene’s lighting. “It felt unreal.” Leonor often moves indiscriminately between fiction and reality through the shared experience of suffering. In doing so, the film gestures toward a set of circumstances in which reality has exceeded its boundaries—in which the scale of harm has moved beyond what should be possible.

Some of the most powerful scenes in the film involve these quiet moments of mutual care—when two mothers sit and acknowledge the impossibility of comfort against such a loss or when a child’s ghost, who’s been nurtured into adulthood, turns on the fan so that his mother will find an announcement for a screenwriting contest. In one of the more surreal moments of an already surreal film, Leonor describes to Ghost Ronwaldo a dream where they, along with Rudie and his father Valentin, are riding on a giant snail. Its slow movements already feel a little like respite against the rapid action sequences that soon follow. Leonor can’t quite explain or remember the dream. “I have no idea where we’re going. I woke up crying,” she says, and then guesses, “Maybe I just missed you.”

¤

Leonor Will Never Die is the work of someone who loves film, even as it engages some of film’s most harmful histories. Part of that love is bound up with the desire to go back, to recut, to make a different edit. At one point during Kwago, Ronwaldo runs down a street after Isabella has been captured by the Mayor’s gang, but intermittent typing sounds interrupt the soundtrack. Ronwaldo looks up and says to the heavens, “Hey! What do you want to happen?” The film cuts to him once again running down the street, this time interrupted by the gentle sounds of music. Clad in ’70s disco apparel, bell-bottoms and a half-open collared T-shirt, Ronwaldo starts to dance.

It’s a fun and funny moment that promises one of many possible departures from the action genre. But even then, in its return to the 1970s context and in its gesture toward the relationship between film and compelled action—“What do you want to happen?”—the moment can’t escape the wider history of martial law. As Apostol writes in “Dancing with Dictators”: “The horror of the Philippines is that its tragedy is best expressed through disco.” Apostol cites, along with Luis Francia, all the violent history that gets left out of David Byrne and Fatboy Slim’s participatory rock musical about Imelda Marcos, Here Lies Love. This includes an event that anticipates some of the hardness of Kwago, her order to bury fallen workers in concrete during the construction of a film center. “Disco is a kind of dictatorship in itself,” in Apostol’s words, “[t]he sense of not being completely in command.”

For Apostol, the rhythm of disco expresses “the tragic absurdity of that past, which is still present.” It’s that same tragic absurdity that Leonor works against, to make space for something else, for a different kind of action hero. One finds a hint of that something else in the title of her script—Ang Pagbabalik ng Kwago—which was also the original Tagalog title of Escobar’s film. The name comes from a ’70s Pinoy rock song that echoes throughout Leonor’s unfinished action movie, first in its original form by Anak Bayan, and later on in the haunting voice of Alyana Cabral and Pan De Coco. The song imagines a world without hierarchy where fighting is replaced with singing and dancing. The owl’s return, in other words, signals something like a change in genre—from action to musical.

After Escobar enters the film to ask if her movie—and, presumably, the history it invokes—will ever be finished, Leonor returns to fulfill the song’s promises. Opening her eyes where her onscreen death had left off, she smiles, widens the frame with her hands, and sings: “They can take everything else, but you and me, nobody else can have. […] I am only happy with you because we are free when we are together.” In multiple registers, the moment feels like an important return. It is prompted by a phone call with Rudie, who, when asked by Escobar how his mother would want this already overdue and over-budget film to end, responds simply with, “Well, she loves to sing.”

When I first saw Leonor Will Never Die at the 2022 Toronto International Film Festival, I spent most of the screening in tears—a stark contrast to the unmitigated joy that filled the theater. Escobar had somehow managed to reach out into my reality, and I felt almost as though I was watching my own lola, who died from COVID-19 in a care home at the beginning of the pandemic; she, like Leonor, loved to sing. I still cannot watch that last musical number without crying, not just because the film unleashed my own deferred grief but also because the effortless and defiant joy of those last moments feels impossible against the cinematic and political contexts that it captures.

Leonor affectionately waves goodbye to the audience, and the film’s end credits play over what looks to be a street somewhere in Manila. It could be EDSA (Epifanio de los Santos Avenue), the street of the People Power Revolution, but here, it is most remarkable for its everyday movements and rhythms. The song playing is Alyana Cabral’s “Ibon at Bala” (“Bird and Bullet”), the same song that played on the radio as Leonor spoke to Ronwaldo’s mother about their sons’ deaths. Blurring the lines between the film world and our own, the song and image hit a melancholy note after a defiant musical number brimming with joy. It serves as a quiet reminder for those leaving the theater, or stepping away from their laptops, of the contexts that Leonor’s song had managed, for a moment, to suspend.

This may not be Leonor’s world, but it is her film. And this film offers, through brief glimpses, a matrilineal structure of care that continues to be obscured by the serialized strain of masculinist politics and suppressed by 500 years of colonialism.

¤

LARB Contributor

Katarina O’Briain is assistant professor of English at York University, where she specializes in global 18th-century literature and culture. She is currently at work on two projects: one on the poetics of dispossession in georgic writing from the 18th century to today and another on the transpacific 18th century, with a particular focus on the Philippines. Her work has appeared in Eighteenth-Century Fiction and Novel: A Forum on Fiction.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Let the Knife Speak: On José Rizal

Gina Apostol explores the works and cultural meanings of the great Filipino rebel-poet José Rizal.

Comparative Authoritarianism: On Vicente L. Rafael’s “The Sovereign Trickster” and Erin Murphy’s “Burmese Haze”

Rosalie Metro reviews Vicente L. Rafael’s “The Sovereign Trickster: Death and Laughter in the Age of Duterte” and Erin Murphy’s “Burmese Haze...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!