Just a Girl and Her Sad Songs: Ani DiFranco’s Memoir

A feminism rock icon muses about her past and her music.

By Sarah HaasMay 31, 2019

No Walls and the Recurring Dream by Ani DiFranco. Viking. 320 pages.

I DIDN’T SEE Ani DiFranco perform until I was 27 years old, which is odd considering how much I loved her and her music. Since her 1990 eponymous debut, spun laboring in a Discman held in my not-yet-teenaged hands, I’ve been literally and metaphorically tethered to her song; long ago her lyrics melded with my thought. Given the strength of my attachment, I’m still not sure exactly why I waited so long to see her perform, and it’s only in hindsight that I can venture a guess: I was protecting the perfect version of the artist who lived in my mind from the one who existed in the real world. During my impressionable years, DiFranco was a level above the other musicians I enjoyed: she was an idol of the woman I meant to become and a beacon for the grunge feminist ethics she’d both invented and defined. Too good to be true …

From my seat in the last row of the balcony at Boulder’s Boulder Theater, I overlooked 1,000 people, mostly women and mostly white, each unique yet unified in their worship of DiFranco. There was no opener but for the house music and the chatter of fans murmuring about what we might see. Would it be 1995’s under-produced but smooth-voiced Not a Pretty Girl? 2003’s Evolve-ing girl turned woman, with a full band? 2012’s political warrior asking us ¿Which Side Are You On? The stage, sparsely set with just a microphone and a large red rug, was open enough to hold all the possibilities, but in its own way it foreshadowed the inevitability of a lonely spotlight cast on DiFranco and her acoustic guitar.

DiFranco hardly stopped playing to talk. The woman who was never shy for words seemed utterly fatigued — as if, after more than 25 years on the road, it was all she could do to stand there and let her lyrics speak for her, guitar faithfully bobbing in tune. But it wasn’t so long ago that that very same guitar had been a stand-in for the world DiFranco railed against, as she beat on its slender body like a drum. What I expected was her defining and central discord. What I got was a melody that was easy and smooth.

From where I sat, I could see row after row of people leaning in toward their neighbors to whisper what I imagined was the question on everyone’s mind: what has become of my feminist hero? Someone nearby murmured about motherhood as a kind of defeat: “She brings her daughter on the road now. She must be tired.” To see DiFranco at that moment in time was to see the singer stripped of her rebellious trademarks — her show wasn’t about politics or femaleness or community; it was hardly even about music. With her eyes closed more often than open, the show didn’t seem to be about anything at all.

Toward the end of her new memoir, No Walls and the Recurring Dream, DiFranco briefly talks about this period in her life: “just a girl and her sad songs,” she writes in the book’s penultimate section. Having thoroughly considered the rest of her life in the preceding chapters, DiFranco finally turns to reflect on the difficulties of having spent a life almost entirely on tour. “I have found myself on stage, searching around for the veils to lift and they just won’t.” The singer-songwriter turned memoirist appears as she did that night I saw her, stripped of her defenses so thoroughly that she has no choice but to just be.

DiFranco needed all of her 300 pages to ready readers to see her so raw. An indie celebrity, she had to write and write and write in order to dispel the many narratives that sought to speak for her. Which is to say that the writing in No Walls and the Recurring Dream lacks the poetic density of her songs in favor of the purposefulness of prose. In an interview with Rolling Stone, DiFranco talks about what it took to write the book: “It feels like sitting in front of a huge slab of timeless stone and staring unfocused until a figure appears, and then chipping … and chipping, and then again un-focusing the eyes.” By comparison, she says, songwriting feels easy, like waiting for the clouds to part and light to descend from the heavens. Despite this difference in method, DiFranco’s memoir undoubtedly bubbles up from the same creative well as her music.

Divided into numbered sections and then further into sub-sections, the book bears the architecture of albums. As if to admit that no matter how much she writes she always thinks in song, the text often breaks into italics — paragraphs and pages that read like a diary’s confessional. It’s in one of these moments of slanted type that DiFranco is able to find and name her source, the zeitgeist of this and all her work: “I want to be free to talk to you as I would a friend […] with a respect that is assumed between us. Can I talk to you as a friend?” Readers can be forgiven for wondering if she seeks to befriend them or her muse.

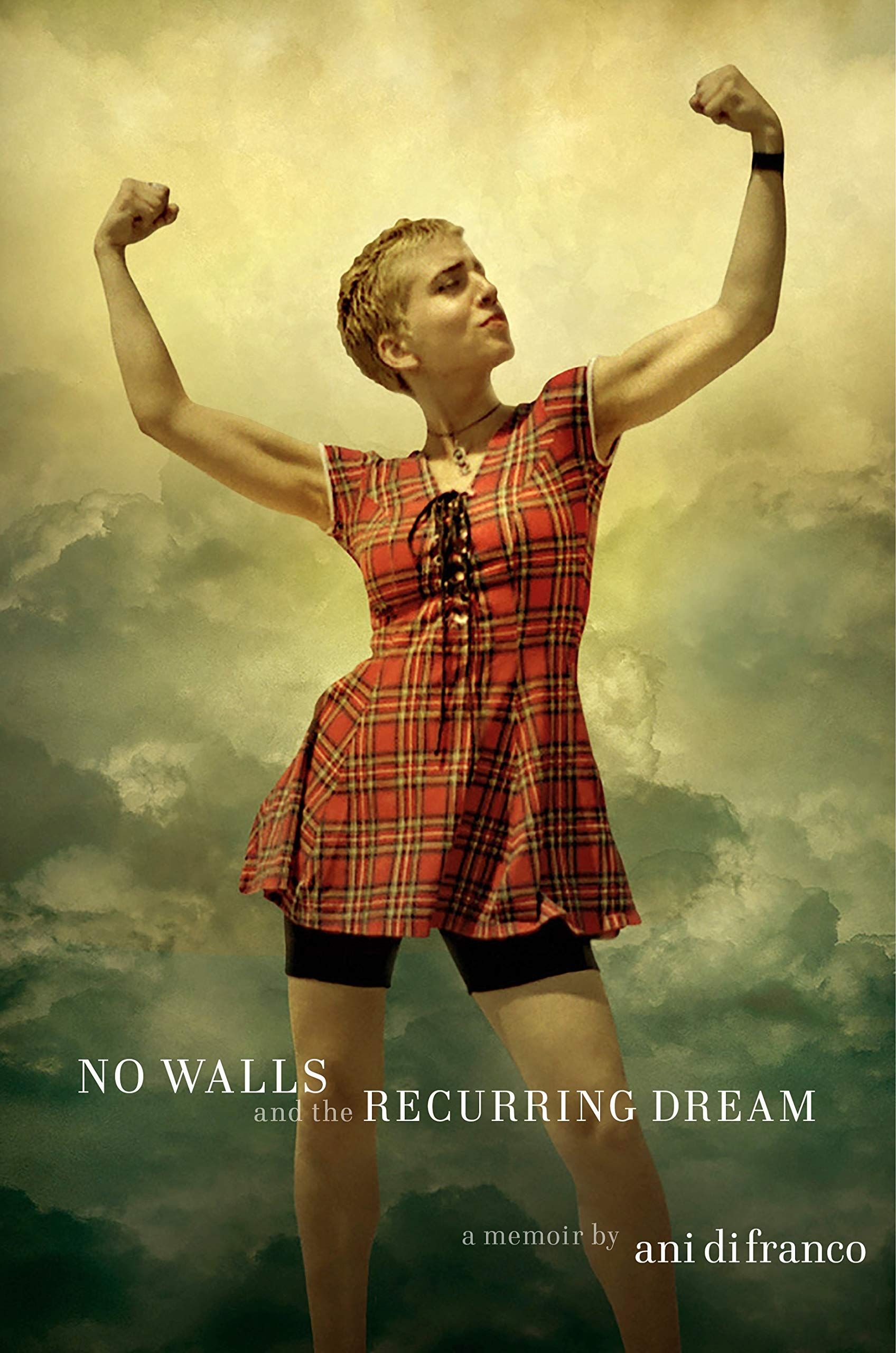

DiFranco (and her publishers) surely know the audience to whom she speaks: the legions of fans who feel, however perversely, that they already know the writer. In broaching the subject of friendship, DiFranco asks permission to break with expectations for the sake of true knowing. In this case, that knowing involves an unlearning of what we thought we knew so as to see the artist as she sees herself — not the brave girl with the pixie cut raising chiseled arms above her head (as depicted on the memoir’s cover), but the woman for whom courage lies in the vulnerability of standing alone on stage, night after night, the sole focus of a single spotlight.

It’s not uncommon for famous people to speak about the ironic loneliness of being publicly beloved, and it’s especially not uncommon for folk artists for whom, as DiFranco writes, “music is a social act to bring people together.” America’s history lives in the work of folk musicians, traveling and collecting experiences, rarely money, even less frequently roots, and transforming the landscape of blue-collar Americana into confessional lyrics offered up in a different quaint venue every other night. The genre has a way of making an audience feel like the stage is a formality, especially in the age of social media when viewers need a reminder that celebrities are more distant than they appear. This realization, though, comes with a sense of heartbreak for both parties — the musician wanting to be known rather than blindly accepted while, for the audience, it’s the other way around.

Aristotle spoke of a form of love — philia, roughly translated as “friendship” — that contains the highest of human virtues. I think that for DiFranco, No Walls and the Recurring Dream is a gesture in that spirit — not a literary masterpiece, but the passion of a woman searching for a friend. There are times in the book when DiFranco presents herself as flawed, even downright unlikable, but given the project’s aim, such an honest portrayal is necessary — and welcome. If we are to know her, we must see her.

Shining a spotlight on chosen snippets of her life, DiFranco uses the memoir to create a self-portrait through a collage of intimate details — the time she had a thing for muscle cars, what it was like to wait at the end of a Mexican bridge for hours on end, the difficulty with which she adjusted to motherhood. Lacking narrative purpose, her efforts at self-discovery avoid the memoirist trap of writing toward a predetermined end; indeed, this book might better have been called an autobiography. By the end, a timeline-driven image of DiFranco emerges, somewhat antithetical to our idea of the artist, yet one that still feels honest and factually sure. Yes, it would be pleasing to see a feminist icon rise up like she does on the cover with her arms flexed, and it would be easier not to be asked to watch the artist creating or the mother birthing, only to witness the art and the child. This is a story with a soul, a reminder that DiFranco’s life, like all life, has been a process of birthing, of always favoring process over product; and as any artist knows, the hardest part of making is reckoning with what’s been made.

As the book winds down, one can feel DiFranco’s mounting anxiety about its impending end, and the last several sections seem a bit superfluous. But having successfully dismantled all the walls, finally standing there, naked and raw, DiFranco enjoys the privilege of being free on these final pages. She offers an interjection from the lyrics to “32 Flavors,” a rambling reflection on the exercise of reflection itself, finally ending with a mother’s reassuring pat on the head: “Even in the mishap and the misery is a collective search for joy. ‘The human spirit’ people call it, though it is by no means exclusive to humans. It is ever expanding. It is infinite, whispers my recurring dream. Don’t worry.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Sarah Haas is an essayist, columnist, arts and culture journalist, and picture book author. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Rumpus, Paste Magazine, Boulder Weekly and various local news publications.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Patti Smith and Male Bias in Music Criticism

David Masciotra makes the case for a major critical reappraisal of Patti Smith.

All the Poets (Musicians on Writing): Courtney Barnett

In this monthly series, Scott Timberg interviews musicians on the literary work that has inspired and informed their music.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!