John Cage’s Endless Project

John Cage's "Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse)" remains full of "good" advice.

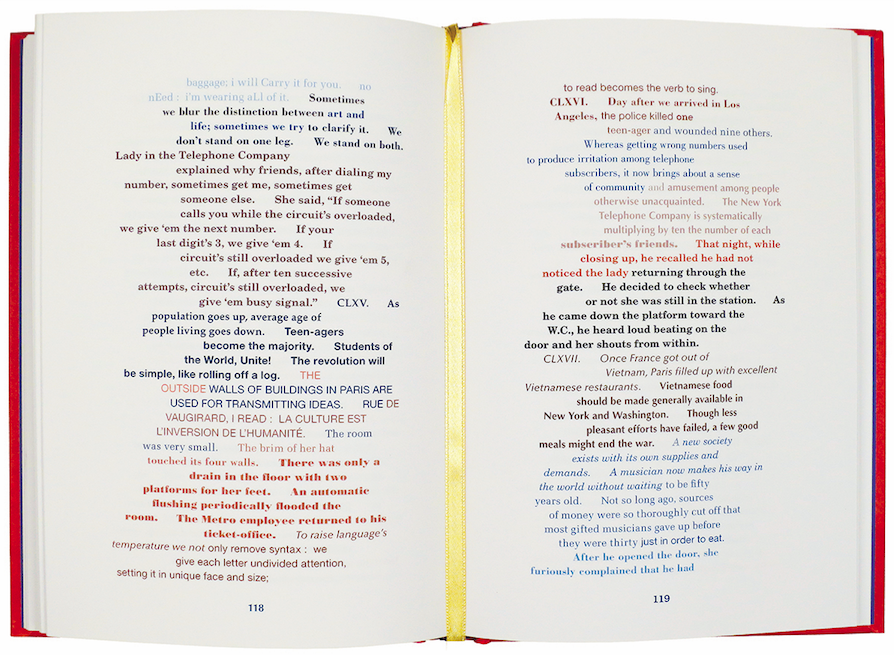

Diary by John Cage. Siglio Press. 176 pages.

JOHN CAGE was very creatively productive up until his death in 1992 and yet is best known for his early work, such as the silent composition 4’33’’, first performed in 1952. Still a powerful source of inspiration — or irritation, depending on whom you ask — this controversial but pivotal work paved the way for new and innovative directions in art. In a 1972 interview, Cage confessed that, at times, even he was prone to “admire my former thinking in many ways more than my present thinking.” He went on to explain that, as he spent more time observing social problems, his theories had become much less clear. “I write about just anything that I notice,” said Cage. “And I think that many people would agree with me that what can be noticed now is extraordinarily confusing.”

What was “to be noticed” in 1972 was a seeming lack of completion or resolution on so many fronts. After more than 20 years of frigidity, the Cold War was far from over. In America, Black Power had replaced the Civil Rights Movement — a reminder that, though laws had changed, culture still had a long way to go — and the Equal Rights Amendment was back in Congress yet again, five decades after it was first proposed. Despite countless protests, the Vietnam War was entering its 18th year.

Cage, too, found himself also in the middle of an endless project. He had begun Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse) in the ’60s and would continue to write and revise and reorganize the work for the next three decades. He was still working on the ninth of a proposed 10 sections when he died.

¤

If the simultaneously helpful and discouraging title of the book Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse) seems to reflect Cage’s feelings of confusion, the book’s text brings that confusion to light. Observations, theories, and quotes bump up wildly against each other; a recipe for beet tops with yoghurt is followed by an account of a visit to an asylum, followed by a critique of modern education, followed by a quote from Chairman Mao, and so on. Cage, like many American artists who came up in the ’40s and ’50s, was drawn to Eastern philosophy, and he often used the I Ching as a way to build the concept of “chance” into his work. For Diary, this meant he tossed coins to determine the order of sentences in each section. The result reads a lot like a Twitter feed, one unrelated quote or thought after another, no segues in sight.

Cage didn’t live to see Twitter, but he was familiar with the similarly disjointed medium of the nine o’clock news. Television newscasts, according to media critic Neil Postman, present us “not only with fragmented news but news without context, without consequences, without value, and therefore without essential seriousness.” Inertia, he argues, is the inevitable result. “What steps do you plan to take to reduce the conflict in the Middle East?” he asked in 1985. “I shall take the liberty of answering for you: You plan to do nothing about them.”

The continued timeliness of Postman’s Middle East example lends credence to his argument. Despite nonstop coverage, our problems haven’t changed all that much. Many of the issues Cage could observe in 1972 remain at a standstill in 2015: the Equal Rights Amendment still hasn’t passed Congress, the Black Lives Matter movement reminds us that racism is as persistent and pernicious as ever, and, this summer, the Pentagon listed Russia at the top of its threat list. The Vietnam War is over but American military involvement overseas is not.

Cage suggests that this is cyclical: a confusing presentation of social issues leads to lack of progress and lack of progress on social issues makes the presentation of said issues more confusing. “One of the things that’s so confusing to us here and so exasperating is that we don’t lack good advice, say from Thoreau, say from Buckminster Fuller,” he explained in 1972. “But our government and the society as a whole pay absolutely no attention.”

¤

Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse), published in full for the first time this year by Siglio Press, and co-edited by Joe Biel and Richard Kraft, remains full of “good” advice, but some of Cage’s choices have weathered better than others. Fuller, whose “comprehensive design science” was praised by Cage and many others, is now chiefly remembered as the inventor of the geodesic dome, a building design so prone to leaks that its most stalwart supporter, Whole Earth Catalog founder Stewart Brand, finally admitted that it was “a massive, total failure.” Cage also makes many admiring references to Chairman Mao. He wasn’t alone in this; throughout the ’70s, Americans who visited China returned with glowing reviews. Mao’s revolution seemed to have done so much in so little time. A 1972 article in Science magazine declared that “Chinese people today are well fed, healthy, adequately clothed and housed, extremely hardworking, and loyal to the present government.” The current official line of China’s Communist Party is that Mao was “70% right, 30% wrong,” but almost everyone agrees that millions died as a result of his policies.

Read through the lens of historical perspective, this seems to explain Diary’s contradictory title: if you try to improve the world by putting it in the hands of someone who designs leaky buildings, or someone whose supporters even admit he was 30 percent wrong, there’s a good chance you will only make matters worse. But it’s not just Mao and Fuller. Even people with much glossier legacies, like America’s founding fathers, don’t have perfect records. Anyone who attempts to change the world — i.e., the day-to-day reality for a diverse group of people — typically makes matters worse for somebody.

This interpretation was probably not Cage’s intent. He was quoting the bright minds of his time, and there’s nothing in Diary to suggest that he believed their ideas wouldn’t age well, even though, side-by-side, they’re often contradictory: Thoreau’s “respect for the individual” versus Mao’s theory that “we must fight self”; Margaret Mead’s hopes for television (“possibility of seeing what’s happening before historians touch it up”) against Marshall McLuhan’s anxiety about that medium. Cage has a vision of a good world — “Everyone’ll have what he needs. Wanting things that are scarce, he’ll make them, find them, get them (as long as the supply lasts) in return for having done something machines don’t do” — but, despite barrels of advice, the question of how to make that world is never answered.

¤

And what of that parenthetical pessimism, you will only make matters worse? It doesn’t seem to fit with the rest of the book, which dips into cynicism only when addressing the subject of apathy. (“Emily Bueno said the reason nothing’ll happen in America to improve matters is most of the people are comfortable the way it is.”) It also doesn’t seem to fit with Cage, who was known for his positivity and idealism, “ready,” as Carolyn Brown of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company has written, “to reveal all his most optimistic Utopian schemes and dreams.” He wanted an end to consumerism, class divisions, and environmental degradation, and for the most part he practiced what he preached, living on the edge of poverty until age 42, when an Italian game show awarded him $8,000 for being able to name “the twenty-four kinds of white-spore mushrooms listed in Atkinson.”

Edible mushrooms were one of Cage’s passions: he taught a class on them at the New School from 1959–1962, and later founded the New York Mycological Society. Mushroom hunting is also one of the major threads running through Diary. “Often I go in the woods thinking after all these years I ought finally to be bored with fungi,” Cage writes. “But coming upon just any mushroom in good condition, I lose my mind all over again.”

This sense of being astounded by the familiar is one that Cage tried to achieve in his music as well. In his 1961 book of essays, Silence, he wrote “If something is boring after two minutes, try it for four. If still boring, then eight. Then sixteen. Then thirty-two. Eventually one discovers that it is not boring at all.” Through repetition, he encouraged his audience to experience old, familiar sounds as new again, from music notes to street noises to a cough in an otherwise silent room. Today, many musicians and visual artists use repetition in their work, but its power is most evident in comedy, where repetition (e.g., the rule of three) is often what makes a joke funny. Kristen Schaal and Kurt Braunohler, for example, have a bit where they perform the same song-and-dance routine over and over. “After the third repetition, people laugh,” Braunohler told the hosts of WNYC’s Radiolab. “But somewhere around the fourth time, it’s really not funny. And then that changes to actual hatred. They’re like, you stupid people, you two stupid people. But somewhere between like nine and eleven they’re like, I like these stupid people.”

None of this seems to have anything to do with improving the world or making it worse, which might be the point. Whenever Diary gets down to details, Cage is more concerned with changing our reactions to the world than with changing the world itself. A brief treatise on recycling, for example, concludes: “This’ll bring about refreshing changes in supermarket design. Staying at home’ll become as amusing as vacationing in a village in Spain.”

¤

Like repeated phrases in his music, Cage’s Diary seems to change with each successive reading. On a third appraisal, time emerges as a theme, as prevalent as mushrooms, maybe even mentioned as often as Fuller. In the early sections, there’s lots of it (“Music’s made it perfectly clear: we have all the time in the world”), but it begins to wane (“If we had immortal life (but we don’t), it’d be reasonable to do as we do now: spend our time killing one another”), until, by the last published section, completed in 1982, “There’s no longer time to correct things first here and then there … Whole thing’s wrong.”

Cage rarely talked or wrote about his personal life, and Diary is no exception. He doesn’t mention his relationship with Merce Cunningham, or any of the complications that their same-sex cohabitation may have presented during the era of Stonewall — although conceivably frustration with his immediate surroundings contributed to his obsession with global change. Still, a hint of the personal sneaks into Diary in the last section, suffused with a sense of panic. Cage was running out of time. He had not, would not, complete this three-decade project. The world around him remained confusing and confused. Jolts of anxiety — “Get out of whatever cage you happen to be in” — are interspersed with reminders to stop obsessing — “What business have I in the woods if I am thinking of something out of the woods?” Through the disjointed text, a picture emerges: 70-year-old Cage walks through the woods, muttering to himself about Watergate, Puerto Rico, South Africa. He’s looking not just for mushrooms but for that old feeling — “I lose my mind all over again.” It’s impossible to find either with Nixon on the brain.

Ignoring the parts of the world that are bleeding is unconscionable. Taking for granted all that is not bleeding is also unconscionable. Always, we are running out of time.

Can we improve the world? Will we only make matters worse? Neither question is answered in Diary. Instead there are schools and governments and city streets, mushrooms and a dream about music that can be eaten, quotes from dictators and inventors and Cage’s Aunt Sadie and this one, from Thoreau: “Yes and No are lies. A true answer will not aim to establish anything, but rather to set all well afloat.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Mary Mann is the author of Yawn: Adventures in Boredom (FSG Originals). She works reference at the Brooklyn Historical Society.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Corita Kent: The Big G Stands for Goodness

Nun, activist, artist Corita Kent at the Pasadena Museum of California Art.

Performance Anxiety: David Grubbs’s “Records Ruin the Landscape”

Records Ruin the Landscape: John Cage, the Sixties, and Sound Recording

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!