NOW THAT WE are well into the second hundred days of the Trump presidency, what are we dealing with, exactly? An aberration, an embarrassment, a chaotic comedy of errors? Or the prelude to full-blown fascism?

The question has been vexing pundits, historians, political scientists, and tens of millions of anxious citizens who not only voted against Trump, but could also not conceive of such a volatile, impulsive, vain, vulgar, authoritarian, and ill-prepared character rising to the presidency. Even now, after several months of exposure to the rollercoaster reality of a President Trump, we don’t know the answer. We don’t even know how long the phenomenon will last. It may be that the sun is setting on a century of American global leadership, and that we are now on an unstoppable path to self-sabotage and doomed to a future of pettiness, irrationality, corruption, cruelty, and growing irrelevance. Or it may be that Trump proves to be a wake-up call, a jolt in the arm to an inexcusably dysfunctional political class, and the sun will soon set on him and everything he stands for.

In American politics, it is not uncommon for a closely fought presidential election to trigger panic that the new occupant of the Oval Office is a crypto-fascist or a treacherous interloper — “the enemy of normal Americans,” as Newt Gingrich charmlessly described Bill Clinton and his Democrat cohorts or, more commonly, “not my president.” Usually, such reactions are driven by emotion more than reality; they tell us more about the blurred lines in American politics between campaigning and governing than they do about the quality of our democracy.

The anxiety about Trump, though, is of a different order. Trump has declared open war on the press, on the judiciary, on law enforcement, on the intelligence services, on the very marrow of the federal bureaucracy. He demonstrates no familiarity with, or interest in, the constitutional limits of the presidency, has little respect for international alliances or treaties, and cannot, even in office, hold himself to basic standards of truth and factual accountability. He talks like an autocrat, shows a preference for the company and leadership styles of other autocrats, and sells himself to his supporters as a strong leader willing to circumvent or do away with government as it has been understood and practiced for generations.

What Trump wants and what Trump can do are not the same thing, of course. Still, history is a stern teacher. Unqualified buffoons have stumbled their way into high office many times, and we underestimate them at our peril. The Italian liberal elite of the early 1920s thought Mussolini was too much of a clown and a thug to last; the German establishment thought much the same of Hitler a decade later. As the Yale historian Timothy Snyder writes in his best-selling short book On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons From The Twentieth Century:

We tend to assume that institutions will automatically maintain themselves against even the most direct attacks. This was the very mistake that some German Jews made about Hitler and the Nazis after they had formed a government […] The mistake is to assume that rulers who came to power thorugh institutions cannot change or destroy those very institutions — even when that is exactly what they have announced that they will do.

On Tyranny began as a post on Snyder’s Facebook page that went viral within a week of Trump’s election. He saw how Trump demonized his political opponents, encouraged thugs to beat up dissenters at rallies, and cast doubt on the validity of the electoral process itself, and he couldn’t help but draw parallels with the darkest days of European history. And it was far from the only warning from a public intellectual with specialist knowledge of repressive governments. Masha Gessen, a Russia expert and biographer of Vladimir Putin, wrote a spine-chilling piece for The New York Review of Books that appeared even sooner than Snyder’s and was designed to familiarize Americans with the tell-tale signs of autocracy in the making. “Believe the autocrat. He means what he says,” she wrote. “Whenever you find yourself thinking, or hear others claiming, that he is exaggerating, that is our innate tendency to reach for a rationalization. This will happen often: humans seem to have evolved to practice denial when confronted publicly with the unacceptable.”

Such warnings have proven to be largely on the mark, certainly when it comes to the new administration’s aspirations. Trump does want his wall, however pointless. He does want to expel millions of immigrants and to ban visitors from Muslim-majority countries. He still talks about muzzling the free press and how he sees millions of non-Trump voters as illegitimate. He has given space in his White House to the radical far right, starting with his special advisor, Steve Bannon. He wants to reconfigure NATO and the whole system of international alliances, and cut non-military government spending to the bone. He has pulled out of the Paris Climate Accord and pulled the rug from under the United States’s free trade agreements.

In other words: Yes, we should have believed what he said as a candidate, even though the words out of his mouth were almost always shrouded in a fog of obfuscation, insincerity, and obvious lies — untruths so blatant that they inspired protest from the start. A funny thing happened, though, as soon as Trump took the oath of office. Americans did see through him, pretty much from the moment he started telling tales about the size of his inauguration crowds. They did heed the warnings of history. They were acutely aware of the risk to American democracy and were not prepared to tolerate it. They took to the streets and bombarded their congressional representatives with emails and phone calls. They formed local action groups and started planning strategies for the 2018 midterms. No moment was more emblematic, perhaps, than when the administration made its first, disastrous attempt to impose a ban on travelers from a seemingly arbitrary list of Muslim-majority countries, and protesters and public interest lawyers came out in force to support the many unfortunates detained at the nation’s airports. “First they came for the Muslims,” read one much-copied protest banner, echoing Martin Niemöller’s famous words about the tragedy of the Holocaust, “and we said … not today, motherfucker!”

It certainly helps that Trump started out as a minority president who won only thanks to the quirks of the electoral college, and that he has shown a singular ineptness in office.

A sly and insidiously subtle Italian statesman once observed that power “tires out only those who do not have it,” yet Trump seems exhausted and frequently overwhelmed by the responsibilities thrust upon him. His White House is a hot mess of competing factions, all furiously leaking to the media about their boss and each other. Trump can’t impose discipline on Congress, even though Republicans hold the majority in both houses. He has alienated career diplomats, career lawyers in the Justice Department, the scientific community, the intelligence community, federal law enforcement, the courts, and many of the United States’s traditional allies overseas.

At the same time, the Trump phenomenon has breathed new life into institutions and political structures that had previously been demoralized, compromised, even moribund. This has become, improbably, a golden age of political journalism and investigative reporting; an age when Saturday Night Live has once again become essential viewing; an age when ordinary Americans feel motivated to pack congressional town halls and demand answers to pointed questions that their representatives have not faced in years.

Trump largely has himself to blame for this turn of events. Instead of learning to wield the extraordinary powers of the presidency and growing with them, he has somehow managed to fumble and squander those powers and appear ever smaller. But it is not all about him. Those who care about democracy and the quality of the United States’s institutions also deserve credit for anticipating the chaos and finding appropriate responses. That does not take away from the gravity of the crisis, or alleviate the risks we continue to face — whether the Trump administration muddles its way through to the end of its term or not. But it does suggest something that Snyder, Gessen, and those millions of Americans afraid of losing their democracy might have underestimated or overlooked: even if we haven’t lived it, we have seen this movie before.

¤

In 1944, The New York Times asked Vice President Henry Wallace to assess the risk of fascism in the United States, and Wallace’s startlingly frank answer was that there were millions of fascists in the country already. Wallace identified a peculiarly American brand of fascist, not a brownshirt bent on violence but rather a charismatic populist interested in poisoning the well of public information and appealing to the public’s worst instincts as a way of accumulating wealth and power. What Wallace most feared was a “purposeful coalition” between “cartelists, the deliberate poisoners of public information, and those who stand for the K.K.K. type of demagoguery.” “They claim to be super-patriots,” he wrote, “but they would destroy every liberty guaranteed by the Constitution.”

Wallace was clearly thinking of the America First movement led by Charles Lindbergh, which has since become a direct inspiration to Trump and his acolytes. But he had plenty of other examples to draw on, notably in the American South, where more than half a century of Jim Crow laws and one-party rule under the Democrats had laid waste to constitutional liberties (notably, the anti-discrimination provisions of the Fifteenth Amendment), and given rise to a rogue’s gallery of charismatic autocrats and hucksters, including James Vardaman in Mississippi, Eugene Talmadge in Georgia, and Huey Long, the “tinpot Napoleon” of Louisiana.

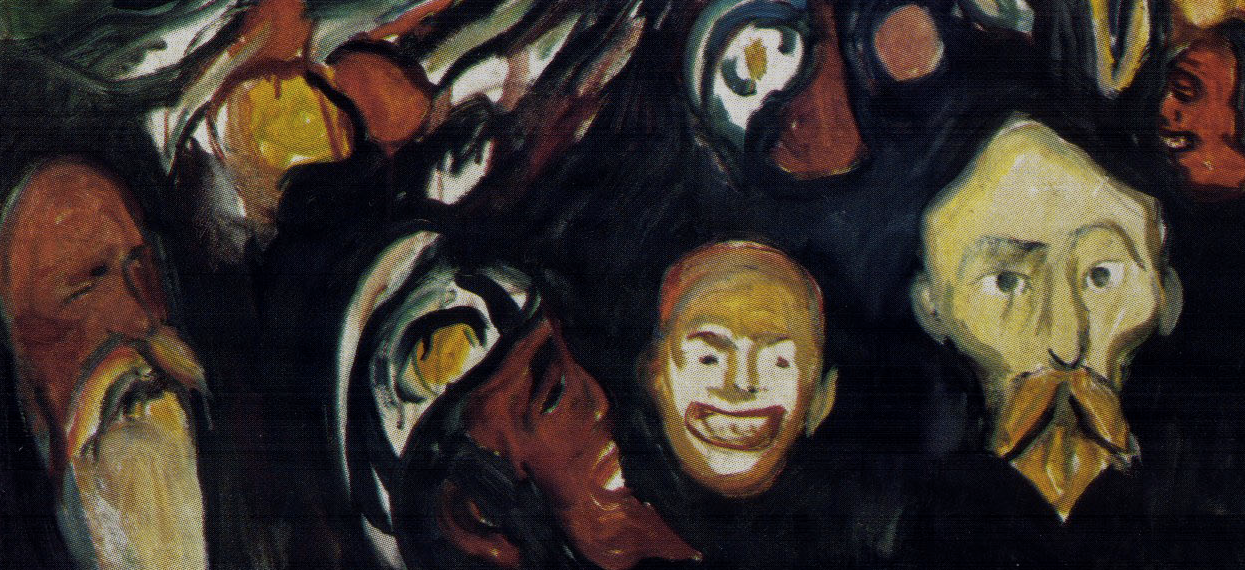

Wallace was an old-school leftist (he was eventually run out of high office because of his perceived closeness to Stalinist Russia), so he was particularly attuned to the drumbeat of anticommunism and to the politics of personal destruction that frequently accompanied it through the radio broadcasts of Father Coughlin, Walter Winchell, and Drew Pearson, precursors to the McCarthy witch hunts that would explode a few years later. This was an era when every weakness of the American democratic system was on garish display — militaristic nationalism, racial discrimination, vulgar electioneering, disregard for workers’ rights, anti-intellectualism, and the mass appeal of religious fundamentalism. Towering over all of these was the rise of a secretive national security state and a mindset akin to what the proto-Nazi philosopher Carl Schmitt once called the “friend-enemy polarity,” the notion — familiar to autocrats the world over — that what most binds a country together is not its own inherent strengths but rather the threat of attack from without. The paranoid authoritarianism of the early Cold War period so unnerved Theodor Adorno that he argued in the 1950 study The Authoritarian Personality that fascism was an ever-present threat in American politics, a sort of cancer that threatened to destroy the fabric of the country at any time. Fascism was, he said, “in the character of the people.”

The threat has ebbed and flowed, of course, and is hardly confined to the United States. To the extent that elections in advanced Western countries are media events, in which politicians package and brand themselves and seek to appeal to hearts as well as heads, there will always be opportunities for silver-tongued charlatans to exploit the worst in people and profit accordingly. Where a candidate gains unfettered access to the airwaves — as Silvio Berlusconi did in Italy, by owning three national television channels, and as Trump did here, through sheer force of his own ratings — the greater those opportunities become, especially in a period of political or economic upheaval. The path to power can become surprisingly, even shockingly, short.

Twenty years ago, the Italian writer and critic Umberto Eco identified the characteristics of what he called “Ur-Fascism,” tendencies in democratic societies that, left unchecked, could trigger something akin to the calamitous 1930s and 1940s. Among those characteristics: a resurgence of religious traditionalism, a scorn for science and intellectual rationalism, a desire to tear down old political structures and disparage long-standing institutions, an uptick in duplicitous political language, mistrust of outsiders, intolerance of dissent, angry re-empowerment of the neglected lower classes, a taste for macho posturing, a compulsion to create popular heroes and villains, and a supreme leader who offers himself as a unique advocate of the popular will.

In the age of Trump, the list sounds unnervingly familiar. Really, though, we have been living with the particulars for some time. We had our first serious brush with Ur-Fascism 15 years ago when the George W. Bush administration responded to 9/11 by issuing stream of untruths about Iraq and girding the country for a war that had nothing to do with the attacks on New York and Washington. In some ways, things were worse then, because the mainstream media and public opinion were largely willing to give the administration the benefit of the doubt. They cheered along as resistant allies were pilloried as out-of-touch appeasers, and said little or nothing when dissenting broadcasters and artists were told to stay quiet. The administration disparaged what it called the “reality-based community” and prided itself on creating its own reality which it sold, in the words of White House Chief of Staff Andy Card, like an automobile manufacturer rolling out a new line of cars.

Our politics have grown only more dysfunctional since. The Republicans are facing significant demographic shifts that threaten to erode their white Christian base, but instead of seeking to expand their appeal — as party insiders have repeatedly urged — they have become ever more extreme, feeding their adherents a steady diet of grievance, division, fear, and denial of reality on every topic from global warming to the “truth” about President Obama’s birth certificate. At the same time, our political discourse is being poisoned by an unprecedented torrent of special-interest money made possible by the Supreme Court’s disastrous 2010 Citizens United decision.

The electorate has become warier and more mistrustful of the political class as a result; it’s one of the few points on which a majority of Republican and Democratic voters can agree. But it has also become dramatically easier for politicians and their consultants to spread disinformation — whether in the form of paid campaign literature or “fake news” — and thus conceal the yawning gulf between their populist rhetoric and their decidedly anti-populist legislative priorities. Voters on either side of the partisan divide would be smart to make common cause against the corruption of the political class and unequal access to power that campaign cash provides, but they have allowed themselves to be pushed into separate party silos and, like angry sports fans, prefer to turn on each other instead.

Seen through this lens, Trump represents both a culmination and a dark parody of where we were heading already. He, like his party in Congress, attained power without winning a majority of the votes — a baffling and alarming state of affairs that in turn reflect the many defects of the American democratic system, from the antiquated idiosyncrasies of the electoral college to the new wave of repressive voting laws introduced by Republican legislatures in hotly contested states like Wisconsin and North Carolina. Trump also benefited from a general weakening of the global order — the cracks appearing in the European Union, the pressure on First World countries from refugees and migrants, misgivings about the impact of free trade agreements on employment and quality of life, and the active interference of a resurgent Russia.

Timothy Snyder points out that in this respect too there are parallels to be drawn between our time and the early 20th century. “Both fascism and communism were responses to globalization,” he writes, “to the real and perceived inequalities it created, and the apparent helplessness of the democracies in addressing them.” Even if Trump proves too inept to undermine the old certainties and replace the liberal democratic order as he desires, the challenges posed by globalization, automation, and digital technology are not going away.

¤

The poisoning of our information sources is arguably the greatest challenge we face in sniffing out authoritarianism and countering it effectively — whether we are dealing with Trump or a future, more functional sort of demagogue. More than 70 years on from Henry Wallace, our capacity for critical thinking has only been diminished by an under-resourced educational system and a free-for-all media landscape that has blown up all notion of what is and is not to be trusted as a news source. The internet has certainly accelerated our descent into confusion, but much of the groundwork had already been laid by Fox News, which for 20 years posited the existence of a biased and manifestly untrustworthy “mainstream media” populated by liberals with an ax to grind and encouraged a generation of Republican voters to believe what they wanted because facts were really just another form of political spin.

It’s hard to exaggerate the damage done by such ideological posturing, and not just because it has helped push the Republican Party ever further to the right. It has destroyed our ability to talk to one another at all. Trump’s habit of promising everything and nothing on the campaign trail, his shamanistic repetition of rabble-rousing phrases (“Lock her up!”, “Build the wall!”), his indifference to being caught in easily provable lies, his belief in his own oracular authority — all these things remind Snyder of what Victor Klemperer wrote about the death of truth during the Nazi era. Now, though, it’s happening at warp speed. Back in the Watergate era, Nixon’s dirty tricksters messed with elections by sending out bogus campaign letters and physically breaking into buildings. Now, in the digital age, Nixonian “ratfucking” has gone both viral and international, as we saw when John Podesta’s email feed became the nation’s breakfast reading, or when purveyors of fake news in Macedonia and other far-flung outposts circulated baseless conspiracy theories about Hillary Clinton and the pedophilia ring she was said to be running out of a Washington pizza parlor.

Has rationalism itself has gone out of the window? That is certainly the fear of Daniel Levitin, whose new book Weaponized Lies: How to Think Critically in the Post-Truth Era is essentially a plea for sanity in a world seemingly gone mad. “[W]e need to reject the idea that truth doesn’t exist anymore,” Levitin states up front. As a scientist and a teacher, he sees the problem primarily in educational terms, urging his readers to familiarize themselves with logical syllogisms and manipulations of statistical data so they won’t be so easily fooled in future. In many ways it is a foolhardy plea — good luck getting unemployed miners in West Virginia to ponder Bayes’ theorem, of which Levitin is an eloquent and enthusiastic exponent — and it may also be a misplaced one. While better education certainly helps produce more desirable political outcomes, it’s hardly realistic to expect the mass of voters in any society to attain advanced logic and critical thinking skills and use them effectively as a defense against abuses of power. Any country whose politics have become as toxic as ours, as infected by big money as ours, as prone to partisan blurring of the truth as ours, is going to be vulnerable to a Trump — or worse. The only adequate response has to be a political one.

What might that political response look like? Some of it we are seeing already, as opposition to the Trump administration continues to harden. The best in government are busy leaking to The New York Times and Washington Post, while the worst — such as Kellyanne Conway, not so long ago hailed as the genius of the Trump campaign — lack all credibility. There are modest indications, too, that the public might be more careful about the information it chooses to believe.

The underlying structural problems, though, are still with us. The flood of unregulated money in politics all but guarantees the emergence of more false populists in the future, in both parties, because true champions of the public interest have effectively been priced out of the market. Congress continues to become less deliberative and more nakedly partisan; in their determination to repeal and replace Obamacare, to take the most recent example, the Republicans have dispensed with committee hearings, amendments, and expert testimony altogether.

There’s no sign, meanwhile, of Fox News abandoning its mission of standing by party first and journalistic accountability a distant second. If anything, the media landscape has become more polarized. MSNBC now tilts heavily toward opinion-driven shows on the liberal end of the spectrum, as a counter-balance to Fox, and cable news as a whole seems less interested in informing or challenging its viewers, only in confirming what those viewers already choose to believe.

Then there is the abiding risk of a major crisis — a real one, like 9/11, or manufactured, like the Reichstag fire — that Trump or another future president could use to accelerate the destruction of the country’s democratic institutions. We’ve seen such abuses of power before: Lyndon Johnson lying about the Gulf of Tonkin incident to broaden the US military footprint in Vietnam, George W. Bush and his lieutenants lying about Iraqi weapons of mass destruction and allowing the right-wing media machine to insinuate that Iraq was somehow responsible for destroying the Twin Towers. Timothy Snyder has expressed serious concern that the 2018 midterm elections — the first opportunity to undo the Republican majorities in the House and Senate — might not even take place if a politically convenient catastrophe should happen to intervene.

It’s an open question whether Trump’s credibility remains solid enough for him to benefit from such a crisis, or whether he would simply be blamed for it. Yes, he is impulsive and tends to lash out when cornered. Yes, he has an instinct for political distraction and had his best presidential week by far when he launched a symbolic but strategically near-worthless missile strike on Syria. But he no longer enjoys much, if any, benefit of the doubt — not with the public, not with the international community, not even with his own White House staff. Still, the vulnerability remains, whether or not Trump finds a pretext to do his worst.

“You submit to tyranny,” Snyder writes, “when you renounce the difference between what you want to hear and what is actually the case.” Unless we learn and internalize that lesson, what in many respects appears to us now as farce can easily repeat itself as tragedy.

¤

LARB Contributor

Andrew Gumbel is an award-winning journalist and author with a long track record as an investigative reporter, political columnist, magazine writer and foreign correspondent. He contributes regularly to The Guardian, among other publications, and has written extensively on subjects ranging from politics, law enforcement and counterterrorism, to food and popular culture. His books include Oklahoma City: What The Investigation Missed — And Why It Still Matters (HarperCollins, 2012), Down for the Count: Dirty Elections and the Rotten History of Democracy in America (The New Press, 2016), and, most recently, Won't Lose This Dream: How an Upstart Urban University Rewrote the Rules of a Broken System (The New Press, 2020).

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Test of American Traditions: Timothy Snyder’s “On Tyranny”

Darryl Holter appreciates the lessons of “On Tyranny” by Timothy Snyder.

The Fascist and the Preacher: Gerald L. K. Smith and Francis Parker Yockey in Cold War–Era Los Angeles

Anthony Mostrom revisits the sordid careers of racists Gerald L. K. Smith and Francis Parker Yockey.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!