Is Cultural Appropriation Ever Appropriate?

Arthur Krystal on cultural appropriation.

By Arthur KrystalJuly 15, 2017

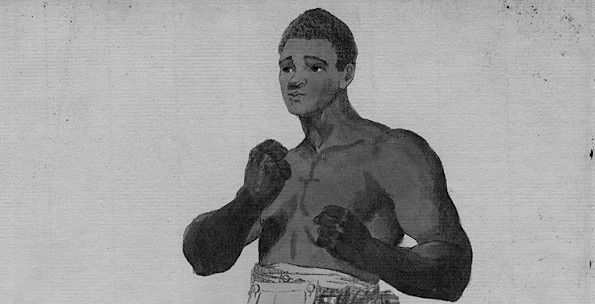

SOME YEARS AGO, I wrote a screenplay about a freed American slave who turned up in London in 1809 and quickly proved himself a boxer capable of wresting the title from the British champion. No small matter, this. England was the only nation on earth where men boxed, and Brits, from hod carriers to Earls, naturally considered the sport the province of Englishmen. A black man contending for the title, especially an American black, was a hard pill to swallow. As one journalist at the time wrote: “It appeared somewhat as a national concern. ALL felt for the honour of their country.”

Although I knew a screenplay was a long shot, I thought this particular story had a decent hook — namely, the rise of a free black community in London and its response to the presence of a loud, brash, powerful African American. His name was Tom Molineaux and he was no less celebrated and controversial a figure than Jack Johnson or Muhammad Ali. The screenplay kicked around Hollywood for a number of years, but no important agent or producer wanted to take it on. Period pieces, I was informed, were a hard sell and, aside from Rocky and Million Dollar Baby (with Clint Eastwood starring and directing), boxing pictures didn’t do much business.

Then one day the Scottish director Gillies MacKinnon read it. MacKinnon gave me notes and encouraged me to rework it as a TV series. By now cable television had become a magnet for edgy material, and TV executives were finally taking a chance on “black” projects. Well, my story had plenty of roles for black actors, and if I integrated (pun mildly intended) more white actors into the story, I could piece together an Upstairs/Downstairs narrative, in which a struggling but thriving black community in London’s East End is set against the scandal-ridden aristocracy of the West End.

So about nine months ago, I turned the screenplay into a treatment for a six-part TV series, broadening its scope to include fictional and historical figures of the Regency period. Currently represented by the largest talent agency in Europe, the treatment is making its rounds of studios, eliciting both enthusiasm as well as regretful demurrals because of prior commitments. Nothing unusual about this, but this time something new had been added to the mix. As one well-known producer put it, the fact that neither the director nor the writer is black is “a huge red flag.” People in the industry, he said, are going to be wary of green-lighting the project.

Yes, it’s true, I am engaged in “cultural appropriation,” which, according to some moral custodians, makes it both unseemly and illegitimate for a Caucasian, however well meaning, to depict a person of color. I, quite literally, don’t have the bloodlines to portray Tom Molineaux, at least not in a creative or fictional format. As it happens, I wrote about Molineaux for The New Yorker in 1998 on publication of Black Ajax, a sly and rambunctious novel by George MacDonald Fraser. Relying on reports by the British press, Fraser presented Molineaux as a brutish simpleton with occasional flashes of insight, whose bad attitude and outrageous behavior are documented by multiple narrators. My screenplay and treatment take a very different tack, and my Molineaux is nothing like Fraser’s. Nonetheless I am guilty of putting thoughts into his head and writing dialogue for black people.

In which case, I am also guilty of theft. According to the legal scholar Susan Scafidi in Who Owns Culture?, cultural appropriation refers to “taking intellectual property, traditional knowledge, cultural expressions, or artifacts from someone else’s culture without permission. This can include unauthorized use of another culture’s dance, dress, music, language, folklore, cuisine, traditional medicine, religious symbols, etc.” This definition appeared in Lionel Shriver’s controversial keynote address at the Brisbane Writers Festival last fall. Shriver, who wore a Sombrero for part of her talk, argued that she had the right to speak in the voices of people whose culture and ethnicity differed from her own. Otherwise, all she “could write about would be smart-alecky 59-year-old 5-foot-2-inch white women from North Carolina.” Upset by the restrictions imposed by cultural arbiters, Shriver confessed that when she started out as a novelist she “didn’t hesitate to write black characters […] or to avail [herself] of black dialects,” but now she is “much more anxious about depicting characters of different races, and accents make [her] nervous.”

One sympathizes, until she asserts that “[m]embership of a larger group is not an identity. Being Asian is not an identity. Being gay is not an identity. Being deaf, blind, or wheelchair-bound is not an identity, nor is being economically deprived.” Really? Because unless one is a Buddhist or the late Derek Parfit, who maintained that identity is too fluid to be any one thing and ultimately doesn’t matter, identity is damn well bound up with race, appearance, background, station in life, and ultimately does matter — if not to you, then to people who know you. Shriver, however, wasn’t being merely provocative; her larger point is that when we

embrace narrow, group-based identities too fiercely, we cling to the very cages in which others would seek to trap us. We pigeonhole ourselves. We limit our own notion of who we are, and in presenting ourselves as one of a membership, a representative of our type, an ambassador of an amalgam, we ask not to be seen.

Sounds reasonable. Or does it? It certainly didn’t to a 25-year-old Sudanese-Australian woman named Yassmin Abdel-Magied, who walked out of Shriver’s talk, describing it later as “nothing less than a celebration of the unfettered exploitation of the experiences of others, under the guise of fiction” [her italics]. Writing in the Guardian, Abdel-Magied accused Shriver of embodying “the kind of attitude that lays the foundation for prejudice, for hate, for genocide” — a not-so-halting statement that makes me think she’d toss my screenplay in a heartbeat, as no doubt would director/producer Lee Daniels who stated flatly: “I hate white people writing for black people. It's so offensive.” Indeed, I suspect that even if I managed to please Daniels, I’d still be an interloper, a talented impressionist doing the police or, in this case, the policed, in different voices.

Although many artists automatically dismiss the arguments of those who seek to censor them, all this angst and anger does have a generative cause: namely, the idea that history gets written by the winners. So, “facts” themselves may be the outcome of various shadings and elisions conceived by those with something to gain. All of which suggests that certain topics and themes may “belong” more to one race than another, and that black writers have a greater moral right to address their heritage than non-blacks. But does this mean that writers should avoid writing about people of another race? That ticklish question came to light 50 years ago when William Styron, urged on by his friend James Baldwin, published The Confessions of Nat Turner. Styron, a native Virginian who came from an “absolutely impeccable WASP background,” spent six years writing the story of the 1831 bloody revolt of a Virginia slave. Whatever qualms he felt in adopting the voice of a slave were, I imagine, more literary than ethical: Did he have the chops to carry it off? Could he create a believable black person circa 1830?

Recounting Styron’s travails in Vanity Fair last August, Sam Tanenhaus makes the nice point that novelists of Styron’s day believed they could do almost anything, that the very nature of fiction invited them, even challenged them, to explain the United States to itself. Styron attempted to do just that, at least in terms of the antebellum South, and, initially, he thought he’d succeeded. Released in the fall of 1967, The Confessions of Nat Turner jumped to the top of the New York Times Best Seller list, won the Pulitzer Prize, and earned its author the distinction of being an “expert in the Negro condition.” Life vied with Harper’s to run excerpts, and producer David Wolper, who eventually co-produced Roots, purchased the movie rights for an unprecedented $600,000.

Styron was riding high, but the praise was short lived. Six months later, he was regarded by many cultural commentators as a literary carpetbagger who had falsified history while playing into racial stereotypes. Aside from getting some facts wrong, mishandling African-American dialect, and not faithfully reproducing the language of early 19th-century sermons, Styron had, without any historical evidence, Turner falling in love with Margaret Whitehead, the 18-year-old white girl whom he subsequently kills.

Needless to say, no white author in his right mind would include such a plot twist today. In fact, between the time that Styron began writing and the time he finished, the racial landscape had dramatically altered. By the summer of 1967, the Civil Rights movement had evolved from nonviolent demonstrations in the South to lethal confrontations with the police in urban areas around the country. The ideals of peaceful resistance and mutual coexistence had given way to a black power movement more in keeping with Nat Turner’s vision of freedom than Dr. King’s hopes for a New Jerusalem. And less than a year after the novel’s publication, William Styron’s Nat Turner: Ten Black Writers Respond recorded the many liberties Styron had taken with the facts. He would never again, so far as I know, be commended for his efforts.

Most white writers and academics, I think it’s fair to say, liberal or conservative, stood by him. The Confessions was a work of fiction, and what errors it contained did not necessarily invalidate it. But if you think there’s no gray area here, I suggest that you set aside 55 minutes to listen to a discussion between Styron and the black actor and activist Ossie Davis. The conversation, moderated by James Baldwin, took place on May 28, 1968, and can be heard online. (You know it’s a ’60s artifact when Baldwin refers to Styron as, “Bill, he’s the white cat over here.”)

The public discussion was prompted not so much by Styron’s novel as by Baldwin and Davis’s concerns that a still-to-be-written movie would depict Turner’s infatuation with a white teenager — a story line that, according to Davis, could lead to the deaths of young black men because “this is one of the areas about which I fear my country can be most immediately psychotic and destructive.” The conversation, with occasional input from Baldwin, creates an impression of two well-thought positions rather than the give and take of a debate. Styron and Davis are unfailingly gracious, self-deprecating, and careful not to disparage the others views.

Styron wants us know that an unexpected irony has occurred, since he desired above all else to write “an honest book,” in which Nat Turner stands in stark contrast to the individual that Thomas R. Gray, Turner’s court-appointed lawyer, depicted in his 1831 5,000-word transcript, which purports to be Turner’s actual confession. That Nat Turner, according to Styron, was a “gifted, intelligent, but totally crazed fanatical butcher,” whereas his simulacrum is “a man of enormous resilience and fantastic vision,” “a liberator,” and “a hero” who represents what “the human spirit could achieve in overcoming the most ruinous and despotic form of human bondage that men have ever imposed on other men.”

Dismayed that people considered his book racist, Styron tries hard to emphasize his laudable intentions. When conceding that his novel ended up doing “some extremely extra-literary things that struck some hideous nerve ends in the public consciousnesses,” he sounds like a man who, in skipping a stone across a lake, somehow managed to create a tidal wave. The opprobrium he provoked reminds him of Baldwin’s statement that the white man has been on the black man’s back for 300 years, and he adds wryly that for the past six months he “may be the only white man who has felt that the entire Negro race has been on his back.” A choice of words that suggests the enormous gulf between a benign white man and those whose great-grandparents were slaves.

Ossie Davis, to his credit, ignores Styron’s clumsiness. Although troubled by Styron’s presentation of a sexualized Turner, he’s even less keen on Styron’s defense of Turner as a heroic Negro. Why should white people presume? Davis’s voice at this point seems to take on both an extra treble and more resonance. Styron, he says with suppressed vehemence, “did not feed me something that I culturally need and there is no way he could do it in reality.” In fact, one of the things he objects to about Nat Turner is “that a white man gave it to [him] in the first place.” The black community, he says, is already speaking a new language, a language forged by experience, whose vocabulary does not conform to white people’s expectations, which is one reason the idea of the heroic black man belongs to black people first and foremost. As the discussion winds down, the audience doesn’t have to figure out who’s right because, as Baldwin noted earlier, both men are right.

As for the film that Davis worried about, it finally appeared in 2016, but it was written and directed by an African American, Nate Parker, who made sure that Turner was not “a sexually disturbed lunatic whose sole motivation hinged on his uncontrollable lusts for white women.” Parker is no fan of the novel and though he mischaracterizes it, in my opinion, as overly exploitative, it’s easy to see why contemporary writers have refrained from emulating Styron’s fictional gambit.

¤

Frankly, when I began a screenplay about Tom Molineaux back in 2000, it never occurred to me that it might be considered transgressive. The Confessions of Nat Turner was old news, and Molineaux was a fascinating figure about whom almost nothing is known. And what a feverish period in British history he lived in. The Regency (1811–1820) was rife with fears of wars abroad and the mob at home, and London itself was host to such charismatic characters as the Prince Regent, the MP William Wilberforce, the journalist Pierce Egan, the fashionista Beau Brummell, the smart Lady Melbourne and her fiery daughter-in-law Caroline Lamb, the courtesan Harriette Wilson, as well as Lord Byron and other members of London’s sporting set.

Presumably, no eyebrows will be raised when actors playing Byron or Egan speak my words, though one is a low-born Irishman and the other is, well, Byron. But black people, apparently, are off limits, which is too bad, since there were some 14 or 15 thousand Africans living in London, with their own stores, eateries, churches, and civic organizations. Surely they must have been stunned, worried, and gratified by that swaggering young man from the United States who had the audacity to challenge the champion and everything the champion stood for. (God, it must have felt good to knock England on its ass.)

All this is dramatic tinder — and who better than I to light it, steeped as I am in the period? Naturally it is much more complicated than that. How could I, a Jewish boy born in Sweden and raised in New York, understand the experience of a black slave? Well, I could do what fiction writers usually do and enter imaginatively into his head, just as I would with a white character. If I did a poor job, I’d suffer the same fate as Styron, and I was okay with that. I also accepted the fact that I’d be given less leeway than a black writer. What was more difficult to accept is that I wouldn’t even be allowed to fail.

Yet why should black writers better imagine Molineaux’s cast of mind? Black people were not merely an oppressed minority in 1810, they were legally considered chattel, supposedly incapable of finer emotions, and thus undeserving of normal human rights. Do you really have to be black to get it? Many ethnic groups, including my own, have at one time or another been enslaved or been the victims of genocide. The truth is, it isn’t bondage that is unimaginable, or suffering, or the evil men do to one another, it’s the absurd ethos that justifies slavery. But while I maintain that it’s no more credible for a black writer to recreate Molineaux’s London than a white one, I also feel compelled to add that I am probably the wrong person to represent the experience of black people closer to my own day.

¤

I don’t say any of this lightly. The history of racial relations in the United States is, of course, appalling. Between 1880 and 1940, around 4,000 black Americans were lynched, sometimes in front of hundreds or thousands of spectators. Segregation was about more than exclusion; it reflected deeply held beliefs and fears about genetics, sexuality, intelligence, and social hierarchies. So when black people marched in 1963 and 1964 in Alabama and Mississippi — and were pummeled and injured and killed — it was because they sought to realign a moral universe, a universe unwilling to budge. It takes guts to face down people who hate you, but it requires a profound commitment, perhaps even grace, to oppose not just the Man but a history in which love of country is equated with the separation of the races. And out of respect for that experience, alien to me in a way that prejudice and suffering are not, I would hesitate to write from the point of view of a black man or woman involved in the Civil Rights movement.

That said, time has a way of, if not modulating events, allowing the common humanity of very different experiences to emerge. The fact that Tom Molineaux lived at a time when conventional thinking dictated that black people were genetically inferior to whites is reason enough for people of all races to write about him. One isn’t so much trying to get into the skin of someone else as endeavoring to show the absurdity of racial assumptions. And though young writers are enjoined to “Write what you know,” it’s not especially useful advice when one doesn’t know much. Because it’s not experience, but what one does with it that makes someone worth reading. Clearly, I don’t know what it’s like to be black or white in 1810 and fight for the championship of England, but, then, who does?

The more salient point is that Nat Turner was allowed to tell his story before he died, whereas Tom Molineaux’s story consists only in what British journalists said about him; and in both cases, a certain skepticism is advisable. Molineaux’s story, however, begs for amplification, and I, for one, believe I can speak for him as well as I could for a Jew who lived in Spain around 1600 AD or in Italy in 1935. No doubt there are any number of people who know more about the Regency than I do, and a smaller number who know more about the free black community in London around 1810, and a smaller number still who are familiar with the London Prize Ring, but I’m pretty sure that none of them knows as much as I do about all three subjects. Does this make me qualified to write about Molineaux? In a word, yes. Whether I do a good job, of course, remains to be seen.

It may not be politic to say it, but politics — whether of the left or the right — should not prevent writers from loosening their imaginations. Unpleasant or not, their choice of subject or approach to it is part of our democratic fabric, and when we discourage writers from writing, we are, in effect, strangling artistic freedom. What’s more, we’re repudiating plain old human sympathy. Empathy exists. It exists because pain, humiliation, suffering, and powerlessness are universal. The particulars may differ, but the sympathetic imagination discerns the common humanity in all inhuman acts.

Styron must have believed this as well. He thought he was writing on the side of the angels, for only an unconscious racism or a deep-rooted innocence can account for his inserting a white love interest where none had in fact existed. No one should begrudge him his labor, though we have every right to judge the result. In the end, it’s the result that matters, not the person who achieves it. So, if a black writer or a Chinese writer or an Egyptian writer wants to write about the Holocaust, which decimated my family, then may the Muse be with you. What do I care about your ethnicity or background as long as you do justice to what happened? It isn’t cultural affiliation alone that does justice to injustice, that creates art from human experience. It’s art that gives life to a depiction of life. And that has about as much to do with the color of your skin as the number of stars in the sky.

¤

LARB Contributor

Arthur Krystal has written for The New Yorker, Harper’s Magazine, The American Scholar, the Times Literary Supplement, The New York Times Book Review, and other publications. He is the author of The Half-Life of an American Essayist, Agitations: Essays on Life and Literature, and Except When I Write: Reflections of a Recovering Critic. He lives in New York City.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“Literature with a Capital L”: On Arthur Krystal’s “This Thing We Call Literature”

Patrick Kurp appreciates the serious “sallies” of “This Thing We Call Literature” by Arthur Krystal.

Taking Down the House: An Interview with Randa Jarrar

Randa Jarrar on white supremacy, glittery bras, and why she still can’t stand white belly dancers.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!