In the Snatches of Free Time: On Collecting Roland Barthes

Ayten Tartici pores over an “intentionally idiosyncratic collection of Barthesiana entitled ‘Album,’” edited by Éric Marty and translated by Jody Gladding.

By Ayten TarticiMay 23, 2018

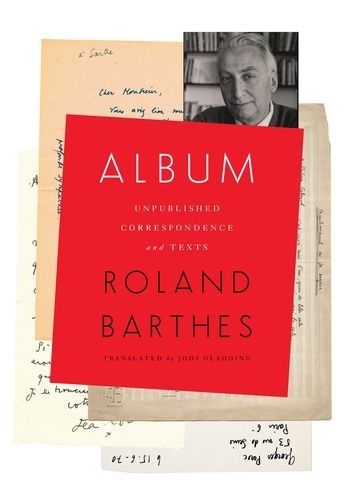

Album by Roland Barthes. Columbia University Press. 392 pages.

IN AN 1885 letter to Paul Verlaine, Stéphane Mallarmé grumbled that all the thousands of bits, shreds, and fragments he had written over the years “make up an album, but not a book” [composent un album, mais pas un livre]. In 19th-century France, the album, echoing its Latin root albus (white), was an actual notebook of blank pages to which one’s friends and acquaintances contributed drawings, poems, and even musical scores (think of it as a yearbook on steroids, assembled just for your enjoyment). In the last course he ever offered at the Collège de France before his untimely death, Roland Barthes revived Mallarmé’s distinction, pitting the album and the book against one another as literary forms: if the album is circumstantial, discontinuous, and lacking in structure, the book is an ordered totality basking in its own architectural design. Mallarmé’s Divagations is an album, he readily agrees; Dante’s The Divine Comedy, a book.

With all those associations in mind, Éric Marty has edited an intentionally idiosyncratic collection of Barthesiana entitled Album, containing previously unpublished correspondence as well as six unedited essays translated for the first time into English by Jody Gladding. The volume is the latest installment in a wave of rolandisme, following the recent publications of Barthes’s unedited diary entries, observations from his stay in China, and lecture notes from the Collège de France. Given Barthes’s painstakingly thoughtful curation of his own life — who else has written a book like Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes or asked aloud, “Should I keep a journal with a view to publication?” — reading these letters can feel a bit like playing Dorothy, finally getting to peer behind Oz’s satin green curtains. The process has all the voyeuristic guilt, the delight of discovery, and the inevitable bathos of getting to live for a few days with the flesh and bones behind your Instagram crush. Instead of ogling their intentionally natural vibe or pensive downward gaze, you get to see their confidence unmasked.

To wit, we come to Barthes’s letters after almost four decades of looking at the photographs by way of which he chose to present himself with: in a trench coat coolly lighting a cigarette with his left hand, the breeze perfectly slanting the flame from his lighter; in black-rimmed reading glasses, surrounded by a book fortress, lodged in his various studies (caption: “My body is free of its image-repertoire only when it establishes its work space”). In his letters, we are instead privy to a writer who is preoccupied with his pace, fretting over the value of his work as the years go by: “I am working, and I am working quite a lot. How much time? Hours and hours each day […] it torments and tires me to be taking so long.” We see him batting down publication requests and patiently soothing those who feel neglected by his withdrawal. “You must never read into my silence; I think of you with much tenderness,” he writes to the photographer and novelist Hervé Guibert. Similar pleas and apologies for his reticence are peppered throughout the letters (most notably to Georges Perec) as is his conviction that he is not really “a man of letters.”

The letters go as far back as Barthes’s adolescence, including his time in a sanatorium, and reach up until his death in 1980, and therefore, cover a wide range of exchanges. One of the longest of these relationships was with his friend Philippe Rebeyrol, who later became the French ambassador to Athens. Letters written to Philippe as early as 1932 shed light on Barthes’s literary formation, and it is remarkable to see almost 30 years later Barthes returning to the same texts he first discovered during those years. Racine emerges as a major influence (“I have also reread nearly all of Racine’s plays, who is to me as Voltaire is to you”), as well as Proust, whom a starstruck 17-year-old Barthes describes as “a prose poet […] [who] analyzes all the sensations and memories that this act awakens in him, as an observer might study all the successive circles emanating from a stone thrown into water.” As Barthes begins publishing more, the correspondences in Album expand to include other French intellectuals. While some of these exchanges reveal new facets of Barthes’s intellectual development, others — such as those to Louis Althusser, Jacques Lacan, and Hélène Cixous — are mostly uninteresting thank-you notes to Barthes for passing along his newly published books. In his foreword, Marty admits to not being able to include letters from Barthes’s most intimate circle — François Wahl, Jean-Louis Bouttes, and Michel Foucault to name a few — and even confesses to destroying the letters the French theorist sent him, an ironic gesture perhaps for a steward of Barthes’s ephemera. (For what it’s worth, François Wahl and Jean-Louis Bouttes did not hold on to Barthes’s letters either.) In addition, while Marty had access to a large collection of letters Barthes wrote to Robert David, with whom he was in love, only a handful of letters to David are reproduced, officially on account of their illegibility.

Do these lacunae advance a particular image of the theorist preferable to other images, or is it about drawing a line around certain matters that will or must remain private? What do we mean when we designate a body of writing as “private”? Is the album, rather than a complete letters, a genre more suited to privacy? Although in The Preparation of the Novel, Barthes argues that “[a] page of an album can be moved or added at random” with an arbitrariness that could lead us to question its value, he also assures us that compared to the book, it is the album that is the stronger form, for the album represents what remains. In adopting the title of “album” for a collection of unpublished letters and essays, is Marty arguing that what he has selected is what really matters, what remains? Not having access to what has been left out, as readers, he is asking us to trust his judgment.

Paradoxically, despite its intentional gaps, Album offers valuable insight, not only into the particulars of Barthes’s life, but also into the themes that haunted his writing, making it a worthwhile resource for Barthes scholars and ordinary readers alike. One of those recurring motifs is Barthes’s complex and sometimes contradictory feelings about the sanatorium as a space of both isolation and camaraderie. Barthes first became acquainted with the institution at the ripe age of 19 during a bout of tuberculosis and over the years stayed at several French and Swiss sanatoriums. He met and fell in love with Robert David (reportedly straight) during a stay at the Saint-Hilaire-du-Touvet facility in 1943. Among the first group of essays Barthes ever penned, and which was culled from the archives at the Bibliothèque nationale de France for inclusion in Album, is “Sketch of a Sanatorium Society.” In this essay, Barthes reads the “theocratic” structure of the sanatorium — in which the doctor is both mocked and obeyed, and is a “miracle worker and hotelkeeper” at the same time — as hostile to the idea of the couple. By suggesting the possibility of happiness outside of the sanatorium’s artificial community, intimacy threatens that highly controlled structure.

Yet, as we know from the letters, that confinement also provided the space for a hidden, sub rosa form of companionship. As Barthes notes, David’s presence makes his stay less painful, his absence more so: “You see, the same routines but without you, my friend, and I suffer a thousand times a day.” When one remembers that an initial version of A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments, with its meditations on the solitude of the lover’s voice, was written during one of Barthes’s many sanatorium stays, these fragments from Album take on even greater meaning. Hints at other forms of company remain in Album, such as when Barthes complains to Georges Canetti: “Two or three intelligent fellows, that’s it. No one handsome, without lowering one’s standards […] All these spineless, mediocre boys with their old flesh that I have known for two or three years, from every angle (so to speak!), what game would you like me to play with them?” “Sketch of a Sanatorium Society” effaces all these personal details, filing them away under the private and focusing instead on the group psychology of its inhabitants within the power structure of the sanatorium. With the doctor at the top and the patients, whom Barthes describes as reverting to the carefreeness of the childhood, at the bottom, the sanatorium is an oppressive space: “It is enough that the patient’s irresponsibility is justified by the inevitable existence of a being, who knows and does not suffer, whereas he suffers and does not know.” This focus on the sanatorium as perpetuating “the irresponsibility of childhood” clashes with the more pedestrian concerns over friendships formed or not formed in the letters, in a way that puts the essay and letters in a sometimes contradictory relationship.

Beginning with the posthumous publication of Incidents (1987), which unearthed Barthes’s explorations of gay desire in Morocco, much has been written on the erasure of homosexuality in the work he himself published as well as his alleged repression and shame. Traces of that hidden life emerge from Barthes’s missives to David, which swing from painfully sincere declarations to conceptual musings. He idolizes David, lamenting the “girlish” tone of his earnestness, while turning at moments to lecture his intended recipient, observing (in a kind of prophecy of affect theory):

Why do our famous psychologists waste their time on contrived topics like Will, Attention, etc., instead of studying the only important thing in modern psychology: Mood? Mood is basically the contemporary form of ancient Fate, that irrepressible power that makes someone different from one day to the next.

Sometimes Barthes’s letters even playfully slip into the third person in an attempt to provide a detached picture of their relationship: “Mood […] a kind of symbol in opposition to classical Passion, the engine of contemporary philosophies, Sartre’s novels, Barthes’s days […] the engine of David’s letters, which […] still cross in groups of three or four […] small lifeless deserts.” There are no letters from David included in Album, leaving us with a one-sided narrative, a soliloquy to an unresponsive Other.

The exchanges in Album also function as a real-time but highly partial catalog of the texts Barthes is reading (Racine, Voltaire, Michelet, and Dostoyevsky) and the music he is listening to (Debussy, Piaf) as well as the to-and-fro of various manuscripts between leading French intellectuals. We see the first note Barthes ever sent to the noted French anthropologist and structuralist Claude Lévi-Strauss, whose publication of Tristes Tropiques had cemented his status at the Collège de France. Barthes’s 1961 note is a plea to him to advise his thesis, The Fashion System, ultimately turned down with the excuse of busyness. Subsequent exchanges between the two spell out their agreements and their differences, including Lévi-Strauss’s strongly worded assessment of Criticism and Truth as indulging in “subjectivity, affectivity, and let us use the word, a certain mysticism with regard to literature.” While earlier Lévi-Strauss warns Barthes against “fall[ing] into a Ricoeurian kind of hermeneutics,” he later gives Empire of Signs more favorable reviews. The exchanges with Jacques Derrida are more effusive but laconic, each man offering brief gratitude and admiration in return. Barthes, teaching at Johns Hopkins at the time, seems ambivalent of his American days (“I don’t want to get started on the written account of my American ‘madness.’ I would risk being unjust [because in short I am against, basically]”). He even compares Of Grammatology to “a civilized book amid barbarism” (meaning perhaps Baltimore) and “a book by Galileo in the land of the Inquisition,” hinting at an air of longing for the Parisian intellectual scene.

Among the most interesting of these conversations is a letter from 1967 in which Barthes stubbornly refuses to sign a political petition penned by Maurice Blanchot. Its content was supportive of the Algerian rebellion and highly critical of Charles de Gaulle’s colonial campaign, calling on writers and scholars not to lend their “words, writing, works, and names” to the “dictatorship” of the Gaullist regime and to refuse to become agents of state propaganda. Barthes disagreed with the content of the text, including the characterization of de Gaulle as a fascist, for political reasons, but also, interestingly, on literary grounds. He had just a few months prior published “The Death of the Author” in the American journal Aspen (it first came out in English). In his response to Blanchot, Barthes identifies the act of signing a petition as a betrayal of that literary agenda: as summoning up an author at the very moment of its death knell.

I always feel repugnance toward anything that could resemble a gesture in the life of a writer. Such gestures occur outside one’s writing but nevertheless give credence to the idea that writing, independent of its actual substance and somehow institutionally, is capital that lends weight to extraliterary choices. How does one sign [comment signer], in the name of a work, at the very moment when we are attacking from all sides the idea that a work can be signed [l’idée qu’une oeuvre puisse être signée]?

This argument was not new territory for Barthes. His disapproval of the act of lending one’s name to a text that itself demands not lending’s one’s name to a political structure — on account of its legibility as a personal message to which the writer’s work could risk being reduced to — derives from ideas he was working on as early as 1946. A previously unpublished essay that precedes the publication of Writing Degree Zero, “The Future of the Rhetoric,” laments contemporary literary criticism’s focus on personal dramas and “chronology” at the cost of a deeper study of rhetoric and style. Barthes would rather devote his time to the fabric of the text itself through terms drawn from his study of linguistics and classical rhetoric: antonomasia (converting a concept into an epithet, the “Bard”), catachresis (stretching common usage, “mow the beard”), and pleonasm (using more words than necessary, “black darkness”). In the same essay, Barthes also denigrates any quantitative or statistical approach to literature, arguing that it produces uncertain and useless results, unconsciously anticipating and dismissing what would eventually be called “distant reading”: “We recognize the barbarism involved in listing the accidents of language for a given writer, and that nothing could appear to be further removed from the spirit of refinement, the customary, glorious tool of literary criticism.” Rather, it is always to rhetoric itself that the reader and critic must return.

Barthes’s worship of rhetoric and style culminates in Album in his slow-motion reading of Flaubert’s Bouvard and Pécuchet. This essay, one of the finest in the book, dissects seven individual sentences from Flaubert’s last novel, meditating microscopically on the traces and tonal colors, all of the sfumatura rising out of a linguistic unit as short as a sentence. He is chasing, as he playfully notes, the “scent of the sentence.” Out of a neutral-sounding narratorial observation such as, “As the temperature had climbed to thirty-three degrees, Bourdon Boulevard was absolutely deserted,” Barthes finds a parody of scientific discourse, the flavor of a maxim and the “sociology of the Paris summer.” Reminiscent of his approach in S/Z, Barthes’s aggressively granular form of reading seeks to break down the complexity of Flaubert’s “analyzable stereophony.”

In the end, the productive ambiguity of Album requires trying to square its deliberate mixture of text and biographical material as well as understanding its self-conscious incompleteness, its status as the antithesis of a Complete Letters. How do we enjoy this compilation without succumbing to biographical determinism? While I do wish, selfishly, that more time was spent with letters to David, their exclusion creates the opening for a kind of unexpected textual longing, a projection of eros into that unspoken space. Perhaps then the answer to the riddle of Album’s biographical material lies in treating these diverse sources more like texts. What is critical is not reconstructing a more “authoritative” version of Barthes, but in using these fragments of correspondences and essays almost as one would the Hadith, as a supplemental layer of textuality to read in conversation with the Qur’an. The selected letters often speak to and against the essays, and some of those contradictions must remain unresolved.

Ultimately, what Marty attempts is not to assemble an image of Barthes the man of letters in his entirety, but to show how even a book of juvenilia, letters, and unpublished projects can, through its juxtaposition of those materials with one another, go beyond mere contextualization and perhaps become something greater than the sum of its fragments. In his final Collège de France course, Barthes notes that the passage of time renders the futures of the album and the book uncertain. It may be that, as time wears on, all that remains in us from a work of literature is a single sentence. That sentence from Dante’s Divine Comedy would be, he says, “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.” Conversely, an author’s untimely death can transform the unconnected fragments that they leave behind into a larger book. Pascal’s death transformed “a mass of unconnected thoughts” produced “in the snatches of free time between other occupations and over conversations with friends” into the Pensées. Time will tell whether Album’s “tableau” will stay an album or whether its idiosyncrasy will keep open the possibility of it one day becoming a book.

¤

LARB Contributor

Ayten Tartici is a PhD candidate in Comparative Literature at Yale. She earned her BA at Harvard, where she studied French, German, and Italian literature.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Derrida’s Quarrel: “La Différance” at 50

Birger Vanwesenbeeck revisits Jacques Derrida’s famous lecture “La Différance” on its 50th anniversary.

Ways of Seeing Japan: Roland Barthes’s Tokyo, 50 Years Later

Colin Marshall looks back on Roland Barthes’s look at Japan in “Empire of Signs.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!