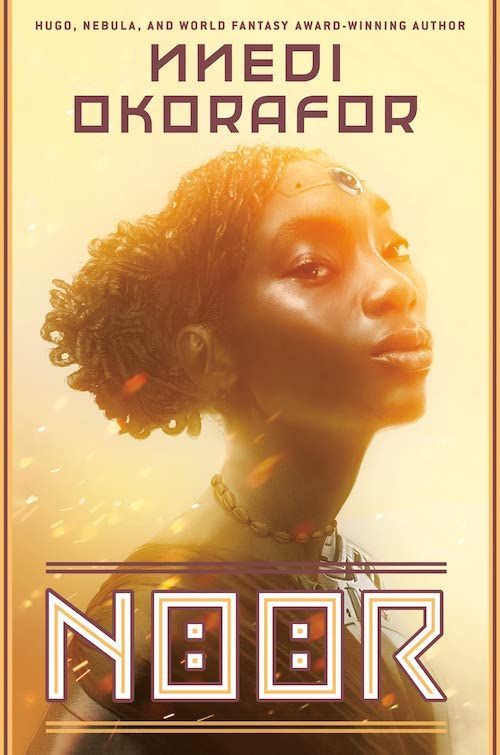

In the Eye of the Sandstorm: On Nnedi Okorafor’s “Noor”

Nnedi Okorafor’s new novel follows a cybernetically augmented protagonist on a perilous journey of self-discovery.

By Ayanni C. H. CooperFebruary 12, 2022

Noor by Nnedi Okorafor. DAW. 224 pages.

IN AN ESSAY on Afro- and Africanfuturism published by the LARB, poet/critic Hope Wabuke analyzes and admires the work of storyteller Nnedi Okorafor. This focus isn’t surprising; Okorafor, of course, coined the term “Africanfuturism,” and her blogpost defining the subgenre and its cousin Africanjujuism sent waves through creative and scholastic spheres. Okorafor is as prolific as she is beloved, having published nearly 30 works in the last 16 years — from comics to novels to picture books — and with over 15 awards and honors adorning her bibliography. In 2021 alone, she published two long-form prose pieces: Remote Control, which has been met with wide acclaim and was dubbed the “anti-Binti” by Dan Friedman, along with the newest addition to her catalog, Noor.

Like many of her previous Africanfuturist works, Okorafor grounds this novel in “African culture, history, mythology and point-of-view.” Noor presents a version of Nigeria a few generations removed from our present moment. In this future, an enormous, endless sandstorm known as the Red Eye swirls ceaselessly over “miles and miles and miles of Northern Nigeria,” and massive machines called Noors gather energy from the natural disaster.

In terms of plotting, Noor provides a fairly standard, serviceable speculative fiction novel. As readers, we navigate the futurescape through the eyes of Noor’s cybernetically augmented protagonist, AO Oju. AO stands for “Autobionic Organism,” a name the protagonist chose in her 20s that gestures to her technologically augmented body. Born with “withered” limbs and disfigured internal organs that were further damaged in a rare “autonomous vehicle” accident when she was 14, the AO readers meet has extendable metal legs, a powerful cybernetic left arm, and a neural implant to help manage her pain. While Okorafor never calls AO a cyborg directly in text, there is narrative parity to larger speculative fiction conventions, especially in the vitriol AO receives for seeming “more machine than human” in the eyes of those around her. The narrative takes off after a group of men with anti-robot sentiments corner AO in a market, sneering a question that Okorafor returns to throughout the novel: “What kind of woman are you?” Though they attack AO viciously, their assault does not go according to plan; AO kills them all in self-defense and flees into the desert, their blood still fresh on her clothes.

Okorafor moves the story briskly after the murder and subsequent escape. AO’s road companion and eventual love interest, Dangote Nuhu Adamu (a.k.a. DNA), a Fulani herdsman invested in tradition, enters the narrative the first morning following AO’s abrupt departure. After recounting his personal tale of murder in self-defense — also in response to an attack motivated by hatred and fear — the two embark on an adventure together. They travel the desert in search of safety and answers, visiting DNA’s nomad village; consulting a weed-smoking wizard; and finally driving inside the terror storm to locate the Hour Glass, a city of outcasts deep in the heart of the Red Eye. During this journey, thanks to a few severe headaches and a rupture in her brain, AO realizes that she can telepathically communicate with a vast network of AI she dubs the pomegranate. Unlocking and publicly displaying this ability to control AI makes her priority number one for Ultimate Corp, the Noor stand-in for our present-day mega-corporations with a name that screams evil corporate empire.

Longtime speculative fiction fans may be able to foresee the steps Okorafor takes to reach Noor’s endgame, replete with AI soldiers, dramatic revelations, the rescue of captured friends, and a final showdown with agents of the novel’s big bad. However, the ways she constructs her futuristic world — and engages with larger conversations around the creation and study of speculative fiction — add interesting wrinkles to the more orthodox narrative.

Okorafor crafts an intriguing hero in AO, pulling on her own experiences with disability and pain to craft AO’s mindset and outlook. In an interview with K. W. Colyard published by Bustle, Okorafor discusses a spinal surgery that “latched” metal to her backbone and required her to relearn how to walk during recovery. Though the process was arduous and complex, she reaffirms the surgery as her choice and “necessary.” Okorafor echoes these linked ideas of choice and necessity in Noor. AO’s story of recovery and navigation of both surgery-related pain and chronic pain are essential to her heroic journey. Okorafor further notes, “I identify with that idea of viewing yourself as a cyborg. A lot of those ideas are what drive [Noor], the idea of accepting and knowing what you are and choosing to move through the world on your own terms.” Readers can see these concepts reflected in AO’s decision to undergo augmentation, even against the wishes of her parents and past lovers, as well as her steely contempt when others reject how she defines herself.

As an augmented human, AO raises arguments around the possibilities and limits of various strains of posthumanist thinking. She frequently asserts that she is a human and a woman, while simultaneously moving beyond humanity’s confines through the powers her augmentations unlock. As Wabuke notes, “For Okorafor, to center Blackness also means to center Black women.” It is not surprising, then, that even as an Autobionic Organism, Okorafor adamantly reinforces AO’s womanness in reaction to the refrain of side characters asserting otherwise. Scholars across the globe have studied how Black women are often dehumanized and somehow simultaneously objectified in our current era. Having AO stand firm in her womanness and humanness pushes against these prevalent — not to mention disgusting — attitudes. That said, I can’t help but wonder what possibilities could be opened by an AO (or through interactions another Autobionic Organisms) less concerned with a limited, human/organic gender binary.

Another of the novel’s critical investments considers and reflects on the current inextricability of nature (or the ideal of “the natural”) and technology. Okorafor uses AO as the most obvious example of this entanglement. However, she further interrogates this idea early in the novel through the story-in-a-story about inventor and world-changer Zagora.

In a fun departure of the novel’s first-person limited perspective, an early chapter “transcribes” episode #8953 of the in-world podcast The Africanfuturist. In the year after her car accident, AO listened to the episode nonstop, using the story as a “bright star to latch onto.” Zagora, a desert nomad girl “born in the sun,” develops a revolutionary technology known as the Sahara Solaris, which converts solar power to a fluffy cloud of energy that travels wirelessly from its initial gathering place to a distant receiver. Zagora agrees to sell her invention to a solar farm company if they agree to her conditions, which she gears toward creating long-lasting, positive effects for the desert and its people. (It remains unclear whether the solar farm company is a subsidiary of Ultimate Corp or becomes it over time, as the novel states solar farms belong to Ultimate Corp elsewhere in the novel.) While Okorafor does not mention Zagora again after this chapter, the plumes of energy appear frequently. Okorafor portrays the inventor’s legacy optimistically, holding her up as an example of how technology can come from a love of environment and its application can do little harm and be immensely beneficial. It is no mistake that AO, on the precipice of dramatic cybernetic augmentation, looks to Zagora as a guiding light. In this way, Okorafor underscores how humans will continue to innovate, and subsequently impact the world around us. However, Noor asks if we will continue in the way of Zagora, who “loved the desert so much,” and the Sahara Solaris or the way of Ultimate Corp and the large, looming Noors.

I would be remiss if I didn’t also address two of my favorite characters in the book: DNA’s cows, Carpe Diem and GPS. GPS, named for his impeccable sense of direction, and Carpe Diem, chosen because she’s an early riser, first appear in chapter two and then consistently thereafter. (Okorafor does shuffle them off-page once the cast settles in the city inside the Red Eye, to my dismay.) They are the only members of their herd to survive the massacre DNA is also lucky to have survived before he meets AO. Okorafor pulls on recent conflicts between the Fulani herdsmen and other groups in Nigeria to construct DNA’s story line, adding futuristic flair to ask questions about the importance and meaning of tradition. Carpe Diem and GPS play into this as the last cows of one of the last active herdsmen. Okorafor makes a point to highlight the cows’ shifting moods and reactions, from vocal protests at wearing sand-repelling gear to always knowing the right moment to have a sit. Carpe Diem and GPS, through their very existence, speak to human interference with “nature.” However, by making nonhuman animals important cast members and considering the slaughtered cattle as noteworthy casualties of the massacre, Okorafor engages with posthuman questions of who merits narrative importance and shows another human/nonhuman bond akin to AO’s with the AI.

Admittedly, GPS and Carpe Diem have stronger characterization than the AI pomegranate. While said to be sentient, “digital,” and “ubiquitous,” the pomegranate remains an enigma. Readers do not get to know the personalities, opinions, etc., of the pomegranate beyond its ever-staring red eyes and willingness to follow AO’s directions. In practice, it functions more as an extension of AO’s abilities and augmentations. While not strictly an issue, learning about the AI — as individuals or a collective — could’ve provided another interesting chance to play with the expected human-centered narrative, like Okorafor did with the cattle.

Noor excels by incorporating interesting philosophical considerations within a familiar narrative frame. As her story unfolds, Okorafor invites readers to contemplate an array of subjects, including questions of self-definition, societal impact, and constructions of community. Additionally, her expert worldbuilding helps to foreground these concepts, while also sparking a sense of wonder for her audience. Ultimately, Okorafor leans toward an optimistic outlook in the novel’s conclusion. Though Noor begins with misplaced hatred and death, it ends on an upswing, giving our heroes a dramatic victory and the rest that they deserve. Using the journey of AO and DNA, Okorafor paints the desert as a place of “infinite potential and hope,” as long as we make the effort to treat both it and each other with care and respect.

¤

Ayanni C. H. Cooper is an English PhD candidate at the University of Florida who studies contemporary illustrated/visual media. She also produces and co-hosts the podcast Sex. Love. Literature., which takes a semi-scholarly look at why the “sex-stuff” in media matters.

LARB Contributor

Ayanni C. H. Cooper is an English PhD candidate at the University of Florida who studies contemporary illustrated/visual media, including comics and animation. Her work has been published by Science Fiction Studies, ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Studies, and Fantasy/Animation. She also produces and co-hosts the podcast Sex. Love. Literature., which takes a semi-scholarly look at why the “sex-stuff” in media matters.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Future Is Divergent: On “Literary Afrofuturism in the Twenty-First Century”

“Literary Afrofuturism in the Twenty-First Century” stands firm in the messiness of it all, proclaiming that said messiness as, in fact, a part of...

The Death of the Future: On Nnedi Okorafor’s “Remote Control”

Dan Friedman reviews Nnedi Okorafor’s new book, “Remote Control.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!