“I Will Not Give You an Answer”: On Laura Riding’s “Experts Are Puzzled”

Kate Silzer considers “Experts Are Puzzled” by Laura Riding.

By Kate SilzerMarch 27, 2019

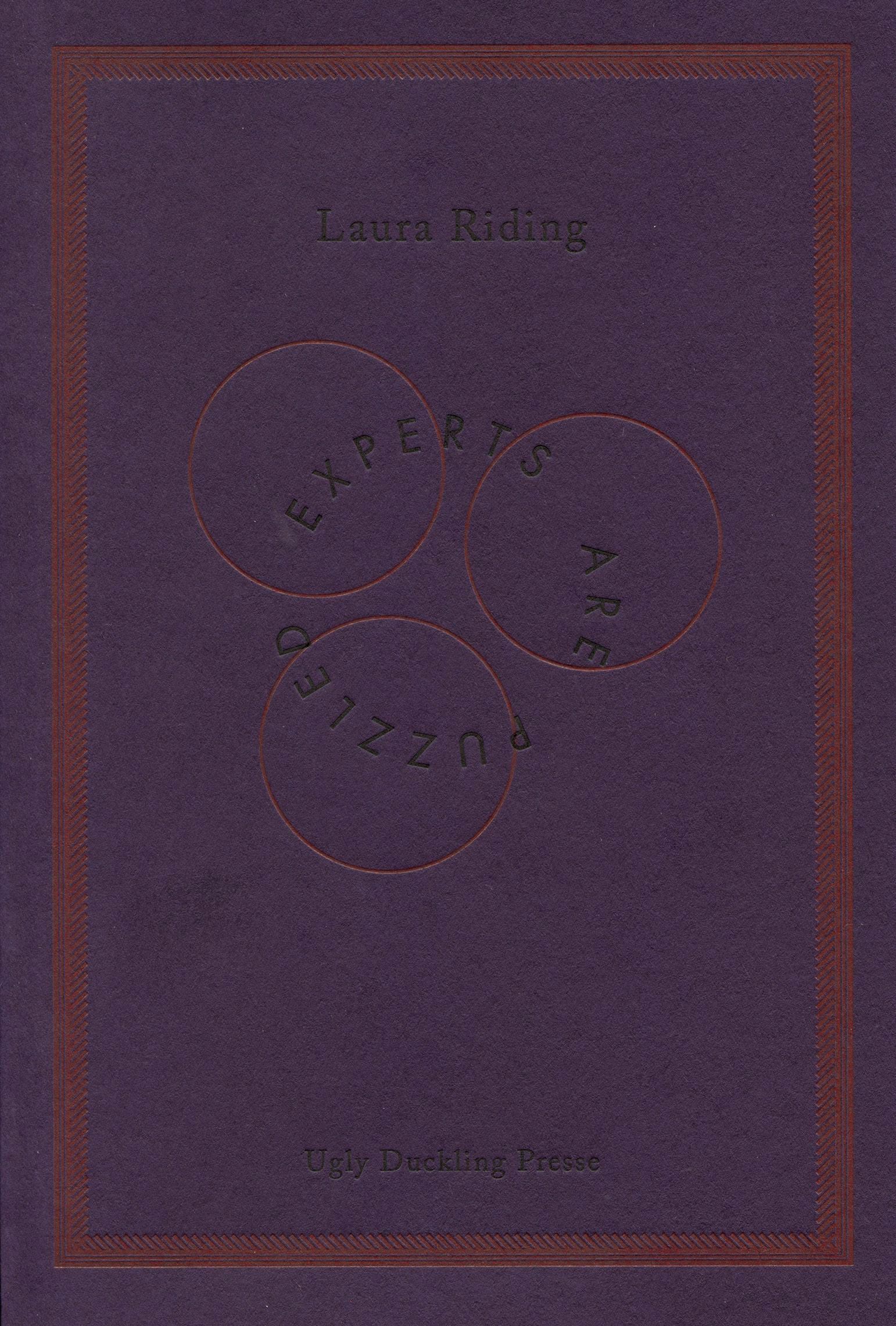

Experts Are Puzzled by Laura Riding. Ugly Duckling Presse. 144 pages.

“Of course my discourse is disjointed, how could it be otherwise? Bring me a complete subject and I will give you coherence.”

— from “Arista Manuscript,” Experts Are Puzzled

¤

A FEW MONTHS AGO, I did something I don’t often do: I bought a book I knew nothing about by an author whose name I did not recognize. Intrigued by the faint circles orbiting the dark purple cover, I picked it up and encountered an exceptionally perplexing string of words:

At least, that is to say, I am a stranger of a fixed old age and I am not puzzled. Ask me anything you like and I will give you a not-puzzled answer. I will not give you an answer. I am a stranger. I do not live, I am only alive. I hear the birds with lice under their wings singing, but I do not understand because I am not a bird with lice under my wings singing. I am not an expert, I am not puzzled.

Originally published in 1930, Laura Riding’s Experts Are Puzzled was reissued in 2018 by Ugly Duckling Presse. The thin but dense collection comprises essayistic fiction, fictional essays, philosophical conundrums, mythical allegories, and elliptical polemics that blur the line between author and narrator.

A first encounter with Experts Are Puzzled is like trying to decipher a map of a foreign city, or being thrust headfirst into a raging river. The 144 pages take the shape of an extended koan, an evocatively, frustratingly impenetrable work. Initially I could only make out the scaffolding: a narrator considers discussing another woman with her handyman, an essay on money begins by asserting “this is not an essay on money,” a creation story hinges on a narcissistic fantasy. There is a candid interview with God. Characters act begrudgingly, if at all. Stories fold into stories. Tangents are followed and abruptly abandoned. Riding relishes running conceptual circles around her readers with rhetoric that takes on the confident stance of logic, but bends, readily and reliably, to the will of nonsense.

By my second and third read through I began to find my bearings; I could swim against the tide long enough to look around, to slow the rushing words. The characters work as stage props more than people, sometimes tactlessly so. They are allegorical vessels for Riding’s real preoccupations: the potential of language to render reality, a spiritual inclination toward oneness, and the way that stories both muddle and reveal truth. Like many writers, Riding is obsessed with the contours of her craft. She writes in spite of (to spite?) the failure of words to exactly emulate the world.

We see her turning over similar themes in her poetry, as in “The World And I”:

This is not exactly what I mean

Any more than the sun is the sun.

But how to mean more closely

If the sun shines but approximately?

What a world of awkwardness!

What hostile implements of sense!

Perhaps this is as close a meaning

As perhaps becomes such knowing.

Else I think the world and I

Must live together as strangers and die —

Riding wants to know “how to mean more closely” with only these “hostile implements of sense,” our imperfect language. How can we know the world fully if we cannot do more than approximate it? This is ultimately her lifelong project, her greatest thorn, and the connective tissue that runs throughout Experts Are Puzzled. What would it mean to access pure truth in language, unmediated by complex interpretation? Her approach to the problem is cubist in nature; meaning is derived from the amalgamation of disparate parts, and the result is gripping.

Repetitive phrases, paradoxes (“I do not live, I am only alive”), and double negatives (“not hopelessly not amused”) reinforce the arbitrary nature of language and add an almost compulsive energy to the text. But these moments of collision also conjure something beyond words — dissonance creates space for a more complete conception of truth. Thinking about it this way locates the strength of her sentences in their roiling tides, how they build and crash. The contradictions create a tension, and this tension enables a sense of balance. In a piece titled “Dora,” which spans just two pages, Riding dedicates almost half her words to this matter:

First Dora asked about the metal strips. They are about eighteen inches long. One is nailed in a horizontal position over the door of my bedroom, the other in a vertical position between two vertical panels within the room. I put them there originally to be a statement, as metal upon wood may be a statement; a statement of one thing, anything, and a statement of another thing, anything, that was equal parts contradiction and affirmation of it, so that together the two strips made a statement of the nature of suspense, which is freedom; that is, freedom is suspense and suspense is freedom; and, further, freedom is everything, suspense is nothing; and so, further, question?

I found myself sketching diagrams in the margins in an attempt to determine whether the string that seems to hold the fragments together actually exists (to mixed results). But this penchant for nonsense is critical to Riding’s genius. She makes her readers do the heavy lifting, or sit in befuddlement, or read a sentence 15 times over. She is obstinate. Certain. Intense. At times, however, it feels as if Riding is drowning in her own style; her sentences overtake themselves.

Still, there is something seductive in this perversion of language, and Riding’s description of sex in her story “Sex, Too” makes an equally good description of her prose: “It is a roundabout way of arriving at a point that could not be found if it were aimed at directly.” The point is not the plot, but the structure: the terrifying largeness of the world contrasted with the contained smallness of a story. Riding’s storytelling makes these contrasts unmistakable as she rations out abstraction and specificity in precise doses:

She was a Prostitute of lost prime, her skirt trailed the dust, and at sunset she began her long, lonely but resolute walk upon the opposite bank of the river, from the Bridge to the Ferry, and then back and then back until the night forgot her. And on this bank small boys followed her Progress, calling a Name, to which she replied with Language. And the men of the Power Station called after her also, and bitterly across the water did she reply; and her replies rang bitterer and bitterer, until the men of the Power Station stopped their ears and thought shamefully of their wives.

Here we’re placed into a scene, laced with inexactitudes, but nonetheless resonant. Then we’re yanked out of it as fish on a line: “And I have nearly told you a story” she tells us. “But no matter, if it makes a smaller world.”

Born Laura Reichenthal on January 16, 1901, Laura Riding — later Laura Riding Jackson — was a prolific writer regarded primarily for her poetry. Her father was a first-generation Jewish immigrant and a socialist. Riding grew up impoverished in New York City, earned a scholarship to Cornell University, and went on to win a poetry prize judged by the Fugitives, a group of Southern writers including Allen Tate. She carried on a notorious relationship with the British poet Robert Graves, with whom she collaborated on “A Survey of Modernist Poetry,” and together established Seizin Press. Known by all to be polarizing, bright, and outspoken, she was a woman who believed she had something to say — and willed herself to be heard. Having spent much of her adult life striving toward a poetic utopian ideal, she ultimately determined poetry to be an insufficient conduit for truth and, in 1940, renounced the form completely. She married Schuyler Jackson in 1941 and settled in Florida, where she focused on other linguistic efforts in pursuit of a new, more accurate paradigm of language until her death in 1991.

Today, her legacy teeters between revival and oblivion (her prose especially, being less considered and less acclaimed than her poetry). A controversial figure who strove to set herself apart, Riding has been called manipulative, obsessive, and wicked, her work deemed both masterpiece and migraine. A 1993 New York Times article lists among her detractors Virginia Woolf, William Carlos Williams, Louise Bogan, Dudley Fitts, and Dorothy L. Sayers. The article continues, “Judging by the caliber of her enemies, we might assume that Laura Riding did something right.” Alongside her critics, Riding also earned her fair share of devoted admirers.

Style is always a matter of preference, and Riding’s style manages to incite both outrage and awe at impressive levels, though the lurid glow around her persona seems to play an outsized role in the discussions of her work. Not that Riding was known to excuse herself from these disputes — as explained by an article in The New York Review of Books by Helen Vendler, she was known to have “spent a great deal of time writing tenacious and extensive letters to anyone who, in her view, had misrepresented some aspect, no matter how minute, of her life or writing.” (She would have undoubtedly hated this review you’re reading now.)

Riding’s personality permeates the page: at once transcendent and forceful, haughty and inspired, earnest and sardonic. She holds the reins with the ruthless brilliance of a deity. “Yes, now I have you in a corner,” she writes in “Obsession,” “you do not know whether to think me mad or subtle, plain-spoken or obscure.” Riding’s writing underscores the messiness in teasing madness from genius, intellect from wisdom, the signified from the signifier.

Throughout her stories Riding takes an unflinching blade to society (“I do not believe that anyone really likes doing anything”), religion (“All have had their chance of being God, God is no more”), capitalism (“[P]ractically everywhere money is talking and where it isn’t there is an awful silence called poverty, or soon death”), and power (“She was so powerful that she had nothing to do but be powerful”). In “The Fable of the Dice,” Riding’s criticism strikes with devastating precision. “There was once a town doomed to destruction,” it opens. “But although doom was certain, they preferred to make it a matter of opinion.”

So, instead of putting the fact of themselves on one side and the fact of doom on the other, they made of these two facts a confusion and hid themselves away in it from responsibility; instead of enjoying time, they marked time. They listened reverently to misty-minded old men who argued one way or the other, to no conclusion.

A few edits would situate this fable squarely in our present political fog, complete with alternative facts and climate change denial. And with so much to say, it’s a shame that her abstruse style so often occludes her message. But Riding wasn’t the kind to compromise for the sake of accessibility. Her work, ironically, requires the sort of elite, “expert” interpretation she condemned. Barbara Adams, author of The Enemy Self: Poetry and Criticism of Laura Riding, wrote that Riding was known to hold the belief that “the reader must meet the poem on its own terms; the poem, however, is not obliged to explain itself or stoop to reader ignorance.” The same can be said of her prose. But to what effect? What is the value of literature if it refuses to meet the reader even halfway?

Still, I admire her unwillingness to bow to critics’ complaints. Sticking with this text, like any good puzzle, reveals and rewards those who persevere through the disorientation. And, like a puzzle, the purpose is as much in the piecing together as it is in the final picture. The text asks you to inhabit two consciousnesses: that of the narration, and that of the act of reading. The value is in watching our minds attempt to decode, to break through, to sort the letters into sense. By noticing the frustrations and the successes, we see more clearly how our minds struggle to interpret, and how we respond when we fail to find meaning.

F. Scott Fitzgerald famously said “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” Riding puts us to this test. Her prose demands work but also surrender — to the rhythm, to the sound, to the contradictions that create this life and everything in it. It is a delicate tightrope walk — one that she walks dutifully if not flawlessly. In this sense, she is a true essayist, in the meaning of to attempt. Her work strives, actively and on the page, in a constant unfolding, backtracking, a waltz that circles and never arrives, exactly, at that elusive complete subject.

¤

LARB Contributor

Kate Silzer is a writer living in New York City. She studied English Nonfiction Writing at Brown University and has been published online in Interview Magazine and Artsy, among others. She currently works as a copywriter in advertising and reads submissions for the literary magazine A Public Space.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Party of One: Democracy, Political Parties, and Simone Weil

A side-by-side reading of a French philosopher and a pair of American political scientists.

Death by Prefix? The Paradoxical Life of Modernist Studies

What is modernism, anyway?

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!