I Was Determined to Remember: Harriet Jacobs and the Corporeality of Slavery’s Legacies

Koritha Mitchell discusses her research for a scholarly edition of Harriet Jacobs’s “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.”

“I HAD MY grandchildren with me. Trying to have a nice time. But that’s what we ended up talking about. I don’t like it. I don’t like it one bit.”

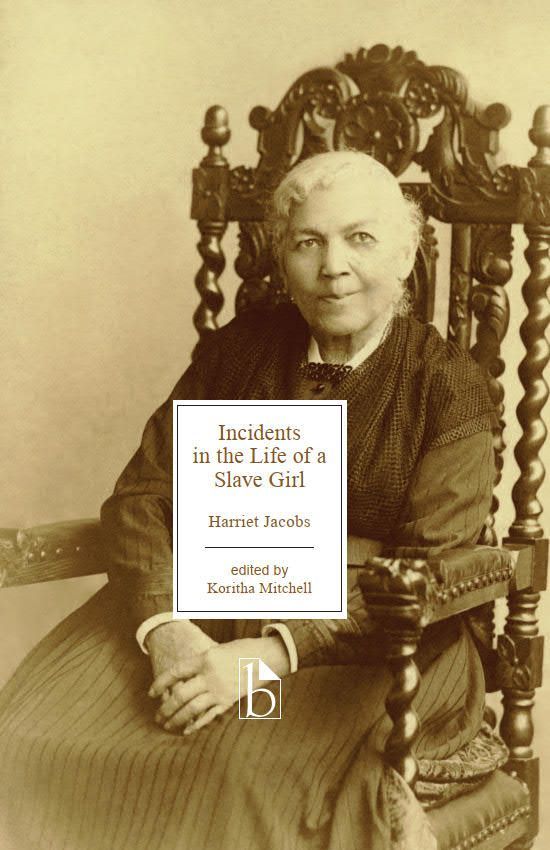

I met Mr. Griffin on a quiet road in Edenton, North Carolina, where he passed our group in his motorized wheelchair and changed direction to come ask what we were doing. I chuckled to myself as he approached. An older Black man in a baseball cap, he reminded me of the watchful elders from my youth whose presence usually kept me from trying to sneak around. What I took to be his nosiness quickly turned into a pleasant conversation about the town. Mr. Griffin had approached our group as a public historian was leading us to various sites related to Harriet Jacobs, who was born and enslaved in Edenton. At age 29, Jacobs escaped to the North. A decade later, she authored the first book-length autobiography by a formerly enslaved African American woman, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861).

Edenton resident Susan Inglis was with us on this tour. She descends from the town’s most prominent families—those who benefited most from slavery—and she knew everyone we encountered. Mr. Griffin was no exception. She nodded as he went from casual ease to intense frustration about the pillory that had been preserved as a historic relic, between the town’s courthouse and jail. The wooden structure is unmistakable. One immediately imagines a person bent over with their head and hands restrained. It is not surprising that Mr. Griffin’s grandchildren began asking questions as soon as they saw this contraption.

Susan kept nodding, acknowledging Mr. Griffin’s frustration. I nodded too. I thought that’s all any of us could do. Then, another woman from our group, Michelle Lanier, stepped forward to address him. There was palpably high regard in her demeanor as she leaned in to look directly into his eyes. He reciprocated—he was all attention. Not startled by her sudden proximity, not defensive. Simply beheld and beholding.

Michelle explained that she was responsible for the pillory he said he didn’t like. As director of the North Carolina Division of Historic Sites, she is responsible for preserving the state’s history. And she owned up, directly and with respect, to the fact that she is the reason the device is there to be confronted.

Michelle’s exchange with Mr. Griffin is one of many moments that lives with me after my first visit to Edenton, birthplace of Harriet Jacobs. I have long treasured Jacobs’s work, but it took witnessing and experiencing Michelle’s embodied intellectual rigor for me to truly commune with Jacobs’s dynamic legacy.

Michelle is a presence. She makes bold choices in self-presentation that somehow never seem over the top. That day, she wore a multicolored coat like nothing I’d ever seen, somewhere between plaid and a rainbow. She also wore a chunky white necklace that hung well past her chest. She told Mr. Griffin that she had left the pillory standing because its presence is a reminder of the torture that took place at the site. It is not enough, in her view, to encounter the town jail when Americans are so likely to think nothing of its cruelty. The United States incarcerates more people than any other nation in the world, but Americans take an out-of-sight, out-of-mind approach to the brutality in our midst. Even worse, the brutality is in our name, supposedly motivated by a commitment to public safety when what makes citizens safer is ready access to food, clothing, and shelter—exactly what so many Americans are convinced only some people deserve.

Michelle and Mr. Griffin talked for several minutes. It was an intimate exchange. The sense that it was okay for me to listen came and went, so I didn’t catch everything that was said. But I was mesmerized by the energy. I witnessed and experienced—even if from a slight distance—the powerful understanding that intellectual engagement is most rigorous when it maximizes embodied connections.

By the time Mr. Griffin rode away, he was promising Michelle that he would have another conversation with his grandchildren. He now appreciated the importance of their understanding what Black and Brown people endured. It was unfair and unjust, but there is nothing to be ashamed of in acknowledging this injustice so boldly. Widely accepted American practices denied these people’s humanity, but when we remember their experiences and their human dignity, we can borrow inspiration as we encounter injustices today.

The group started walking again, following our guide to the cemetery designated for African Americans, and I watched Mr. Griffin roll away with a new perspective. As had already happened several times, I was in awe of the power of how Michelle moves in the world, a public historian whose foundation is folklore.

I’m a literary historian and a performance studies scholar, so long before meeting Michelle, I thought I understood the significance of storytelling and of embodiment. But that weekend in Edenton keeps unfolding for me because she guided me through a deeper appreciation for the insights that emerge from fleshly memory, fleshly intelligence.

Never taking embodied knowledge for granted, I have long argued that it is intellectually lazy for scholars to operate as if they can float above material conditions and above the implications of how their bodies are read. That is why I address how common I know it is for white teachers to use racial slurs in their classes, to immeasurably harmful effect. My podcast episode The N-Word in the Classroom: Just Say NO has been made required listening by institutions throughout the United States and beyond because it encourages embodied self-reflection, which people considered white seldom undertake. Likewise, my appreciation for embodiment’s impact on intellectual rigor shapes my professional-development workshops, in which I insist that it is not enough to acknowledge other people’s disadvantages in the classroom, workplace, or nation; those who claim to care about addressing inequality must also confront their own unearned advantages—such as those that come with being read as able-bodied in an ableist society.

My investment in bringing corporeality into intellectual work landed me in Michelle’s presence in Edenton. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, I had signed a contract to produce a scholarly edition of Harriet Jacobs’s autobiography. Executing my vision was daunting, but I knew I had created a volume unlike any other because it requires the reader to consider the body they inhabit while they engage Jacobs’s life story. The very first line of my introduction is “Can you get pregnant?”

Month after month, I kept myself motivated to work through the mountain of scholarship on Jacobs and her remarkable text by posting on social media. When I submitted the manuscript on my birthday, July 11, 2022, I announced that I had done so in time to make a radio show appearance before going out to dinner. A colleague of Michelle’s reached out to propose a book launch in Edenton in the summer of 2023. When the three of us met (virtually), Michelle ended the conversation by asking, “Don’t you want to visit Edenton before the launch?”

I agreed and we hung up, but afterwards, I realized that it never would’ve occurred to me to visit Edenton without this invitation. I wondered why, but I quickly shrugged and got on with my day. I later learned that Michelle is so familiar with this tendency—to dwell with texts but never set foot in the place that produced them—that she considers such invitations to be part of her work.

Equating the South with virulent racism creates a disconnect for many Black people, including scholars (like me) whose research revolves around African American experience in the region. Over the years, Michelle has noticed how mythic representations of the South as a place teeming with violence overshadow dynamic lived realities, and she works to loosen the grip those myths have on countless Americans. As a graduate of Atlanta’s Spelman College who has lived in North Carolina for the most part ever since, Michelle encourages people to participate in a process of loosening imaginative chains. And so, for a weekend in November 2022, this Houston native encountered Michelle’s “womanist cartography.” After experiencing its signature combination of storytelling and self-reflective embodied practices, I will never be the same.

¤

I flew into Raleigh, North Carolina, and spent the night, knowing Michelle would pick me up first thing in the morning, along with two other scholars. We all got acquainted on the two-hour drive from Raleigh to Edenton. We asked Michelle how and why she had created a career so equally entrenched in academia and public history. Michelle has taught at Duke University for more than 20 years, she has produced documentaries that reach beyond university walls, and she oversees 26 museums and historic sites throughout North Carolina. Michelle’s response began during that car ride but was interspersed throughout the weekend. She lives her answers.

Michelle is a folklorist and cultural preservationist, and she is intentional about how she encourages people to experience the past and present of a place. In a 2021 interview, she shared her guiding methodological question this way: “How can I connect my calling—being a keeper of memory for myself and my communities—to the people I welcome into these spaces?”

Just as she gently guided Mr. Griffin to appreciate what might be gained by engaging the pillory that still stands between the courthouse and jail, she held my hand physically and metaphorically throughout the weekend. Just as important, she pointed me in various directions and helped me point myself in a few others. What I mean might be explained by what happened on another part of our walking tour.

Harriet Jacobs hid for six years and 11 months in the crawlspace above her grandmother’s storage shed. She took desperate, ingenious action to avoid the devastation she believed would follow if her enslaver, Dr. James Norcom, succeeded in executing his plans. He had started building a cottage where Harriet, then 15 years old, would be sent to live, in order to be at a distance from his jealous wife and constantly available as his concubine. Anyone who has read Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl is familiar with how close to him Jacobs was while in hiding: she often saw him going to and from work. Our tour group walked the short distance between Jacobs’s hiding place and Norcom’s office.

For Jacobs, seeing Norcom moving about in such close proximity inspired stomach-turning terror. However, Jacobs eventually gained the confidence and resources to write Norcom letters that convinced him she was already in the North. As a result, Incidents describes not only the misery of being cramped and terrified for nearly seven years but also the feelings of triumph when Jacobs watches Norcom leave for New York because he is sure he’ll catch her there.

The building in which Norcom practiced medicine remains intact, but Jacobs’s hiding place is no longer as it was in the 1800s. A True Value hardware store now occupies that space. My heart dropped. We were standing where Jacobs endured crushing darkness, an infestation of bugs, frostbite, and hallucinations, but there was no indication of what transpired there. Before I could articulate my thoughts and the feelings that accompanied them, I heard Michelle’s voice again. She was always guiding us through story, through memory, through embodied practice. She was asking, “Do you remember how Jacobs begins her autobiography? In the very first paragraph, she highlights the fact that her father was a skilled carpenter. And now, at the site from which she orchestrated her freedom and kept her tormentor confused, there is a store where carpenters come for supplies.”

With this, Michelle reoriented me not only in that physical space but also in my mind and heart. I have taught Incidents for the past 18 years in nearly every class because it is such a crucial text for understanding American culture. Jacobs navigated state-sanctioned sexual vulnerability because the United States built its economy on treating people as chattels, as movable pieces of property. In that context, “chattels” who could become pregnant were treated as breeding animals that just happened to resemble human beings.

Crucially, Jacobs wrote Incidents in a way that emphasizes how fiction and nonfiction at once collide and collude. In telling her life story, she constantly highlights the law—the real-world statutes that certainly have real-world impacts—while at the same time exposing how much imaginative effort it took for legislators—who were all white men—to treat Black women as if they deserved no rights. White men’s authority was based on fictions preferred by people who could rely on the power of the armed state as they declared their human equals to be their natural inferiors. So, I have consistently taught Incidents because it sheds incomparable light on American culture, then and now.

Jacobs begins Incidents by honoring her father:

I was born a slave; but I never knew it till six years of happy childhood had passed away. My father was a carpenter, and considered so intelligent and skillful in his trade, that, when buildings out of the common line were to be erected, he was sent for from long distances, to be head workman.

Michelle encouraged my embodied engagement with Jacobs’s story by bringing my attention to an astonishing feature of the fence outside the True Value hardware store: the fence has a hole the size of the one that Jacobs created to bring air and light into her hiding place.

As a folklorist and cultural preservationist, Michelle has developed a methodology she calls “womanist cartography” that involves creating “restorative maps.” Dominant discourses and practices elevate straight white men’s perspectives at the expense of other citizens, so the built environment tells a story in which white men make contributions and never commit crimes. Engaging landscapes while telling Black women’s stories inevitably shifts one’s encounter with a location. This practice of restoring memories honors those whose humanity is denied whenever their experiences are disregarded. However, erasure weakens the connections that make us all human. Therefore, when we use our own storytelling capacity to engage those usually erased, our humanity is restored along with theirs.

In this case, the True Value hardware store—and the fence lacking a marker to acknowledge what Harriet Jacobs experienced there—tells the story preferred by dominant American culture. A society that built its wealth by treating the sexual exploitation of Black women as a necessary nonevent was never meant to acknowledge that Jacobs existed, never mind that she outwitted the man whom the nation empowered to dictate her fate. And yet, outwit him she did.

By calling my attention to the one-inch hole in the unmarked fence, Michelle used our physical proximity to tap into an embodied intellectual and spiritual alliance with how, in her dungeon of a crawlspace, Jacobs preserved her soul and sanity. Standing at that site, I felt pride knowing what took place there but also anger that Jacobs was erased. I also felt honored to trace Jacobs’s steps in person, not simply as I had by reading and teaching Incidents. While I wrestled with a complicated mix of feelings, Michelle gave me tangible reasons to dwell with the sense of pride and inspiration. I had taught Incidents so many times. But looking at the smooth contours of the wood’s unexpected opening, I felt connected to the experience in a new way. I focused on the sounds and sensations of my body’s proximity to the place my imagination knew so well.

Even though nothing matched what I had imagined, I suddenly felt surrounded. Not only was Jacobs there, but so were her son, her daughter, her uncle. Jacobs had a hiding place above her grandmother’s storage shed because her uncle constructed it, complete with a trapdoor through which food could be passed. Incidents testifies:

My uncle had left [a gimlet] sticking there when he made the trap-door. I was as rejoiced as Robinson Crusoe could have been at finding such a treasure. It put a lucky thought into my head. I said to myself, “Now I will have some light. Now I will see my children.” I did not dare to begin my work during the daytime, for fear of attracting attention. But I groped round; and having found the side next the street, where I could frequently see my children, I stuck the gimlet in and waited for evening. I bored three rows of holes, one above another; then I bored out the interstices between. I thus succeeded in making one hole about an inch long and an inch broad.

Michelle invited me to join her in placing a finger next to the hole in the fence, to appreciate the size of the opening that sustained Jacobs for almost seven years. I didn’t know I could be more in awe of Jacobs. Tears made my vision blurry, but also clearer than ever, as I looked at the women, equally moved, with whom I was sharing this experience.

Moments like this keep unfolding as that weekend continues to impact my mind and spirit. Fleshly memories and fleshly insights visit me often, sometimes enveloping me. I have never been so aware of the presence of ancestors, their wisdom, their emotion, their love and support.

Michelle’s womanist cartography insists that “paper and screen are not enough to hold these stories. The maps must be two-dimensional, yes, but they must also be performative, aural, visceral.” Because Michelle helped me feel the significance of that one-inch opening in the unmarked fence, I hear Jacobs speaking to and through me. For instance, I now see and feel that Jacobs did not simply use her father’s carpentry expertise as a frame for her life story by beginning her narrative with it. When she emphasized the gimlet that empowered her to carve the one-inch opening, she also testified to her uncle’s skill as a carpenter and his determination to make his love for her palpable through it.

Time and time again, Jacobs’s narrative highlights how—in a nation economically addicted to her sexual exploitation by white men—loving Black men and being loved by them is a sustaining force. At age 15, she had fallen for a free man of color who wanted to purchase her freedom and marry her. Norcom not only refused; he also vowed violence against the man: “[I]f I catch him lurking about my premises, I will shoot him as soon as I would a dog.” This becomes a turning point in the narrative because Jacobs changes her definition of womanly success by relinquishing her goal of becoming a respectable wife and mother. Incidents testifies: “[H]ard as it was to bring my feelings to it, I earnestly entreated [my beau] not to come back. I advised him to go to the Free States […] He left me, still hoping the day would come when I could be bought. With me the lamp of hope had gone out. The dream of my girlhood was over.” Alive with my embodied experience of Edenton, I hear another Southern ancestor, Zora Neale Hurston, adding her voice to Jacobs’s: “[Her] first dream was dead, so she became a woman.”

Around the time of her sweetheart’s departure, Norcom told Jacobs that he would build the cottage for her. To thwart these plans, she encouraged the attentions of another white man of high social status, future congressman Samuel Tredwell Sawyer. The United States made her body available by default. She at least wanted to influence how it would happen.

Even as the Founding Fathers spoke of self-determination, they created a society in which only white men had a right to it. Jacobs left a record of sovereignty asserted in the narrowest of spaces and despite the most confining legal, social, and political conditions. In ways that preserved her dignity, she maneuvered through the sexual vulnerability she could not avoid. And yet, she crafted her narrative to emphasize how agency and free will were achieved in community—a collective that includes African Americans of all genders and ages. Black men’s love is expressed in concrete ways and joins with that of her children and her risk-taking grandmother to make possible what the United States was designed to prevent: dignity for a Black woman, not just pleasure, power, and profit for white men.

¤

Michelle gave me a priceless gift by inviting me to Edenton and guiding me through a particular experience of its geography. I now see and hear and feel my ancestors communing with me on the page and off.

When I received the contract to produce an edition of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, I did not know a pandemic would change my life. Finishing the project took longer than expected, and I have struggled throughout this time in ways I could not have imagined. However, as my Edenton experience lives with me, I feel in my flesh what I grew up calling “blessed assurance.” It helps me recognize what I managed to preserve despite the twists and turns of the past few years. When I proposed the edition, I wanted to highlight not only Jacobs’s sophisticated and relentless engagement with the law but also her laser-like focus on incarceration. Jacobs’s prose is so elegant that the reader can initially overlook how forcefully she indicts that which usually goes unquestioned. Audiences are primed to miss her critiques because no one has escaped the message that certain populations simply must be cordoned off and controlled.

Jacobs understood that imposing the fiction that certain people deserve no rights requires not merely lies; it takes lies bolstered by, and reinforced with, violence. I therefore wanted my edition to help audiences notice how frequently Jacobs brings attention to patrollers, to sheriffs, and to jails. I link Jacobs’s clarity to the current historical moment, where the United States leads the world in placing people under surveillance and in bondage, and where women are the fastest-growing population behind bars.

I made and stood by an unconventional decision, and my communion with ancestors since that weekend in Edenton keeps convincing me that my resolve was significant. I created an appendix entry based on a short film by Lorna Ann Johnson called Freedom Road (2004). Representing a film on paper is impossible, but I wanted to include the voices showcased in it. The film features incarcerated women who participated in a class about memoir and autobiography. Incidents is one of the texts the students engaged, and it empowered them to value their own stories—stories brutally erased by the normal workings of the United States. Freedom Road communicates on two registers, reverberating geographically and in embodied and emotional ways. The title refers to the street leading into and out of the prison. It also refers to the path created in the women’s minds, through their active reading and writing, long before they have access to the physical road.

I am convinced that representing the women’s voices will lead readers to connect to the lived experience of Jacobs as well as to the women who could better cope because they had encountered her story. In their words on the page—even without images, moving or still—I hear and see and feel Jacobs’s approval of the appendix as a space where generations of readers will encounter these women’s testimonies from 2004, along with Jacobs’s own from 1861. My communion with the ancestors therefore reminds me of the power of communing with the living as well.

Michelle has said, “Every story my grandmother shared was a map and a monument.” After recognizing the gifts her grandmother gave through storytelling, Michelle could more fully appreciate the legacy left by so many other Black women of the South. She testifies, “I was determined to remember. And I did.”

I am also determined to remember. I trust Mr. Griffin is too.

¤

LARB Contributor

Koritha Mitchell is the author of From Slave Cabins to the White House: Homemade Citizenship in African American Culture (2020) and Living with Lynching: African American Lynching Plays, Performance, and Citizenship, 1890–1930 (2011) and editor of Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (2023 edition) and Frances E. W. Harper’s 1892 novel Iola Leroy (2018 edition). She is also president-elect of the Society of Senior Ford Fellows (SSFF). Follow her @ProfKori.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Historian Forgotten: On Andrew Diemer’s “Vigilance”

Bennett Parten reviews Andrew Diemer’s “Vigilance: The Life of William Still, Father of the Underground Railroad.”

Octavia Butler and the Pimply, Pompous Publisher

How my 14-year-old self commissioned sci-fi writer Octavia Butler in 1979 to write an essay that still resonates today: “Lost Races of Science...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!