Hurt Just the Right Way: A Conversation with Emi Nietfeld

Natasia Pelowski speaks with Emi Nietfeld about her new memoir, “Acceptance.”

By Natasia PelowskiDecember 13, 2022

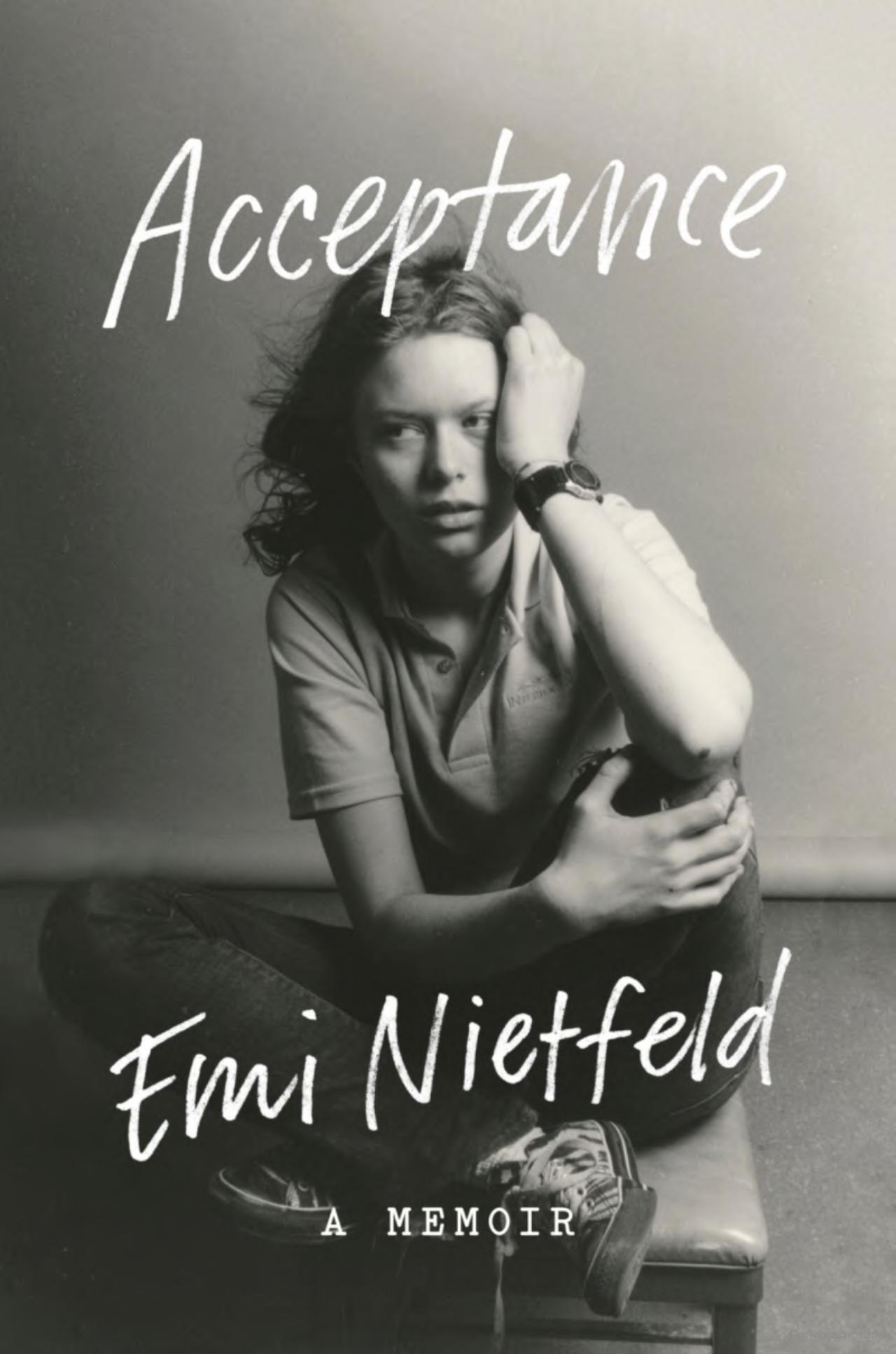

Acceptance

EMI NIETFELD’S NEW MEMOIR, Acceptance, investigates what it means to survive. Her story begins in the uninhabitable — a house that reeks of mouse urine and other consequences of her mother’s hoarding, the comparative cleanliness of a psych ward after her own suicide attempt at 13, a troubled teen treatment center, foster care, and the car she lived in after becoming unhoused.

Despite child welfare and family systems that repeatedly fail her, Nietfeld intuits at a young age that the way we frame our lives might reshape them. During the college application process, Nietfeld learns that buzzwords such as homeless prove more exciting and worthy of an acceptance than phrases such as teen treatment center.

Acceptance transcends typical resilience narratives by questioning what survival costs, acknowledging both Nietfeld’s pain and privilege. She states, “I learned how few acceptable ways there were to need help. You had to be perfect, deserving, hurt in just the right way — even then, adults were so constrained in what they could offer.”

When I opened Acceptance, I stayed up all night. As a research associate for PTSD projects and former high school dropout, I am often mired in trauma narratives, passionate about how voicing our stories can liberate our past from being confined to others’ interpretations. I developed an obsessive memoir-reading habit early in life, finding inspiration in the ways others survived trauma and found validation in their emotional experiences. But I spent years questioning why the term “survivor” never fully captured how trauma can reassert itself into the present, never acknowledged how many factors are outside of our control, and never felt like the compliment so many books made it out to be. Nietfeld’s Acceptance offered clarity on topics that have haunted me: questions of privilege, resilience, and children’s rights — or lack thereof.

I met Nietfeld at the Sant Ambroeus Coffee Bar on Park Avenue in New York City. We took a stroll to Central Park, where we settled on a shaded bench near the 59th Street entrance to discuss her debut memoir, Acceptance.

¤

NATASIA PELOWSKI: I am in absolute awe of Acceptance. I was arrested by your investigation of privilege and the role it plays in resilience. Did you set out to explore this from the start, or did it come through the writing process?

EMI NIETFELD: Once I better understood the facts of my life, I started to get asked by a lot of people, “How did you make it?” As if those people were looking for a secret that could be applied to other people. I had to dig. As a culture, we like to believe it’s some character trait or moral goodness that allows certain people to persevere. But when I looked back at the facts of the story, I noticed factors that I had been given by my parents, by religion, and by the specific flavor of religion I was raised in. I didn’t want this book to be like Hillbilly Elegy and imply that if I can do it, all these other people can, and they’re just choosing not to — that’s not the truth. I didn’t want my story to be a weapon that people could use against the disadvantaged. Some factors were privilege and some were misfortune, but I wanted to be honest about all of them.

I was struck by the intensity of your dream — the ambition unwavering from day one. What allowed you to cling to that yearning so early? How did you hold fast to that dream throughout your life?

A big part of it came from religion. When I was a young child, I went to churches that pushed the idea that God had this big plan for everyone: if you work hard, pray, and believe in God, that plan will come to pass. So I had this mythology, right? It was this mythology of having control over your destiny. When it came to college, my mom had a dream about going to Stanford. When I was growing up, she would always talk about how different life would have been if she got into Stanford. It was like, “Oh, it’s cold outside. If I got into Stanford, I would be in California right now.” Or, “Oh, your dad is not helping me with anything. If I had gone to Stanford, I would have married a great man, I would have been a doctor, and he would have helped out at home.” And I believed it. I believed that if she had gone to this different level of university, every single part of her life would have been different or easier. It made this abstract tool of college concrete.

There’s a theme of powerlessness throughout your story, not just by misfortune but by the nature of being a kid. Children don’t have the same rights as adults. In theory, our systems are structured this way to help children meet their needs, but, as your story illustrates, removing a child’s agency often proves problematic. Did ambition serve as a way to overcome that powerlessness?

I’m really glad you asked that because it’s something I think a lot about. When I was in mental health treatment, as a preteen and a teenager, I was very aware that, because I was a minor, they could make me do anything. Because my mom was an adult, they couldn’t make her do a single thing. That infuriated me. So yes, retreating into my ambition and my dreams was the only way that I felt like I had control. And there’s a point early on in the book where I’m in this locked facility for troubled teens, and the counselors take away all my books. And they say, “Those are not appropriate; you need to only be reading teen fiction from now on.” And that made me so angry because it felt like they were trying to break me. They were trying to take away the one thing that I had. It made me resolve to hold on even tighter.

That’s moving. I’m sorry they took your books.

In the long run, it galvanized me. I don’t like the whole idea that what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. But I do think that, as an individual, you can make your own lemonade.

You mention that counselors couldn’t change your mom’s behavior. If there was an ideal situation, is there an action you would’ve hoped for?

Make her get rid of stuff. She had a severe hoarding disorder. It made it so that we didn’t have a decent place to live. As a child, it felt like such an obvious thing that somebody could come to the house and say, “You have to get rid of this stuff.” Right? Or threaten some kind of punishment if she didn’t. As an adult, now I understand how hard it is to make an adult do anything. But it seems like a huge flaw in our system. If you are a child in [the United States], you can be locked up for any reason. Your parents can send you to a boot camp, an evangelical rehab, a Teen Challenge, or even an international reform school.

Children become vulnerable simply because of their age.

Exactly.

This power dynamic is especially evident in the first half of your memoir — only the adult opinion is treated as valid. As a reader, there’s tension because we have the context to see the narrator is often right, but the narrator doesn’t have that context. Repeatedly, her opinion is discarded, or she’s gaslit — at times, it feels like she has no voice in her own life. Zooming out, this lack of agency points to a larger, systemic issue. I’m hesitant to ask if you have a solution because I don’t want to place that burden onto survivors, but I wonder if there’s anything you wish you’d known when you were younger? Or anything you’ve learned from writing this book or growing older?

I recommend a book called Childism: Confronting Prejudice Against Children by Elisabeth Young-Bruehl. In the book, the psychoanalyst argues that childism is a form of discrimination in ways similar to racism, homophobia, and anti-Semitism. Particularly, in the United States, we don’t believe children have rights. Part of it is political — where certain people who are often religiously conservative believe that parents should have all the rights, that they should have this enormous power to wield over their children. It’s not like this in every country. I’m probably going down a rabbit hole here. But there’s this whole UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the [United States] refuses to ratify this.

Right! I remember learning that during a psychology internship and was blown away that the United States was one of two countries that wouldn’t agree that children have rights.

Yes! and the other one was Somalia, right?

Yes. [In 2015, two years after Childism was published, Somalia ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, making the United States the only country that has refused to ratify.]

I’d love to hear what you think of the resilience adage that everything happens for a reason.

I definitely don’t believe that everything happens for a reason. I do think one of humans’ great gifts is to come up with reasons for things, which can be powerful, but in my experience on this topic, after I got into Harvard and graduated, I felt that I had to make everything that had happened make me stronger. It all had to have a purpose. And it was my responsibility to find that purpose. Because if I could do so, all this bad stuff that happened to me would then make the world overall a better place. It was a kind of moral obligation. And it was crushing. It made me miserable. Because it wasn’t possible.

Absolutely. I appreciated how Acceptance kept returning to its own narrative, questioning which interpretation of your life was accurate. How did you organize your thoughts around the different versions of your reality and find what was true for you?

I wish it had been a matter of organizing these different areas. Instead, what happened is I had to go through each of them. For a long time, the story of my life was the story my mom told, where I was crazy, I was bad, I caused a lot of trouble. In this view, eventually, I got with the program and started being good. Then good things happened to me. Later, when I went through the medical records, I was so ashamed because I thought that what my doctors had written in these notes was the truth and was the real story: a story in which I was histrionic and dramatic. That I was always claiming or denying things. This language is super suspicious and blaming. And it was only after years of writing the book, and going over these narratives again and again, that I was even able to privilege my own viewpoint.

How did you feel when you released the book?

To my surprise, I actually felt ready. I worked on it for seven years. I felt ready the week before, but it was because I worried about it for so many years prior.

What was your favorite part of writing this memoir?

Oh, that’s such a good question. The most important thing in the writing process was being able to say the truth of exactly what happened and have another human being read it and say, “You’re still okay as a person.” I’m fangirling over my editor — I feel like I can tell her anything, and we will figure it out together. It’s a type of supportive alliance that you hope to have with a therapist. But I don’t know if I ever had that in my life before. So that relationship, in and of itself, has been really healing for me. It’s also been just super meaningful to me to hear from people who are like, “I needed this” — and especially other people who have been told that they need to be resilient or need to be thankful, from all walks of life; to feel [we are] on the same team; to hear people say thank you for acknowledging this pressure.

¤

Natasia Pelowski is a writer, yoga teacher, and research associate in New York.

LARB Contributor

Natasia Pelowski is a writer who lives in New York. She is also a yoga teacher and a research associate on projects related to the prediction and prevention of traumatic stress in children. Her recent work has appeared on NBCNews.com.

LARB Staff Recommendations

When Addiction Fails: On Carl Erik Fisher’s “The Urge”

Gordon Marino reviews Carl Erik Fisher’s “The Urge.”

Empathy and Solidarity: On Alejandro Varela’s “The Town of Babylon”

Alex Espinoza talks with Alejandro Varela about his debut novel, “The Town of Babylon.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!