I WAS RAISED in what used to be a sleepy suburb five miles from the center of Athens. I remember desolate summer afternoons with the world asleep during the siesta hours. We had an ancient black and white TV, but there was no TV to watch, just two dismal state channels with endless news and parliament sessions. At midnight, the national anthem would play behind a blue and white flag waving in the wind; a childlike animation of the city turning out the lights would dwindle to one last lit window — then the picture would go blank. The stores always seemed to be closed. Someone was forever waking up, or going to sleep, but never there. My parents would wait in line for hours to buy a stamp. At the tax office they were sent to floors that didn’t exist, then waited in more lines for more stamps — this time, inexplicable multitudes of stamps which would eventually be plastered to important documents then ink-stamped by angry civil servants. The big-handled, unwieldy, spring-loaded ink stamps were the symbol of our complicated lives. The bigger and louder the crashing stamp, the more important the employee. We waited; we learned to wait. We waited for Godot, but we were happy — it was 1985.

My father loved C.P. Cavafy (1863-1933). With a scowl of deep concentration, he would read poems like “Ithaca,” or “The God Abandons Antony.” He was amazed that this scrawny, reclusive dandy from Alexandria could be so powerful in his verse. It was the magic of poetry at work, or as poet Glyn Maxwell says, “what’s signaled by the black shapes is a human presence.” He had the collected poems of Edgar Allan Poe — the French went crazy for him, he would say, and a treasured volume of his most beloved François Villon, the first real bad-boy of medieval poetry. There was Kostas Karyotakis and of course Nikos Kazantzakis — mostly novels, but my father loved to point out that Zorba, the “greatest Greek of all” wanted “here lies a Greek who hates the Greeks” chiseled on his tombstone. Nobody but the poets can articulate this conundrum, this love-hate, madness of being Greek.

What does this have to do with poetry or losing our way? Greece has gone from knowing itself as a quiet, Mediterranean/Balkan backwater with a great literary and political history to an overhyped European fraudulence almost overnight. Poetry will not fix the economy or punish the Greek political elite for ransacking the country, but before we even begin to think about economics, something needs to restore order in the average Greek’s proud and angry soul.

¤

In 444 BC, Herodotus wrote of the Persians, “the most disgraceful thing in the world, they think, is to tell a lie; the next worst, to owe a debt: because, among other reasons, the debtor is obliged to tell lies.” We are not Persians, but Greece lives on debt and lies. If the collective guilt is there, it’s covered up with anger and tear gas. Once we started driving borrowed cars and propping up the world’s impressions with Olympic monstrosities and ad campaigns, we could not go back. The much-celebrated Olympic games in 2004 were a double-edged sword. It raised Greek morale, but destroyed the economy in an excessive show of false opulence and order. Most of the glamorous purpose-built venues are now useless decomposing building sites. The government was so desperate to impress the world, they erected giant screens to cover up ugly neighborhoods, they sent cab drivers to “etiquette school” and I still remember the absurdity of watching workers roll out kilometers of sod on the neglected parks the day of the opening. Cafes all over Athens mimicked the “traditional look” of the cafes we tore down in order to make way for Starbucks. Elegant neoclassical Athens was bulldozed in the 1950s for the concrete hell of apartment boxes whose design is the aesthetic equivalent of a garbage dumpster. The organ grinders are gone, the innocence and simplicity is never coming back, and there will be no solace in the banks of other countries, in the ridiculous ethnocentric propaganda we’ve been fed since birth, the insanity of the right wing with their fraudulent religious façade, or the latent violence paraded under the mask of “traditional values.” In an ideal future, a dream world where the politicians have sold their last lie and the TV stations have exhausted their last banality packaged as news, the poets will be heard. Here is Cavafy:

“Ionic”

Because we’ve smashed their statues,

because we’ve run them from their temples

does not mean that all the gods are dead.

O land of Ionia, they love you still,

it is you their souls remember.

When an August dawn breaks over you

your air pulses with their life,

and sometime the shape of an ethereal youth,

invisible, in rapid flight,

sprints across your hills.(trans. Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard)

Throughout Greece’s tumultuous history the poet has served as the voice for the silenced people. Greece has always been a hornet’s nest of trouble and corruption, as well as a victim of perpetual war and occupation. When Greece’s great poet, Kostis Palamas (1849-1943) died, Angelos Sikelianos’s (1884-1951) fiery poem and eulogy roused 100,000 citizens at the funeral into a furious demonstration against the Nazis. Later when brothers killed brothers and masked Greek informers betrayed their own neighbors during the civil war in the 1950s, poets like Yiannis Ritsos’ (1909-1990) delicately wrought poems were an antidote to suppression, violence, and censorship. In the 1960s the military coup turned the struggling republic into a police state, a shadow play of CIA operatives, torture, executions, and student massacres. At that time, poetry entered the culture through music. George Seferis (1900-1971) wrote “Denial” as a love poem, but it entered the national consciousness as a song against the military junta after the composer and songwriter Mikis Theodorakis set it to music (b. 1925):

On the secret seashore

white like a pigeon

we thirsted at noon;

but the water was brackish.On the golden sand

we wrote her name;

but the sea breeze blew

and the writing vanished.With what spirit, what heart,

what desire and passion

we lived our life: a mistake!

so we changed our life.(trans. Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard)

In September of 1971, thousands of Athenians marched through the city following George Seferis’s funeral procession; the entourage made its way toward the main cemetery, chanting the lyrics in protest of the dictatorship. It was the beginning of the end for the generals. Even today if someone starts the tune at a Greek dinner party, not a soul of a certain generation can resist joining in. I have attended events in Athens during which the entire audience has spontaneously erupted with this music, and this poetry. It is in the bones of every Greek who lived through the dictatorship. It is the literary equivalent of an evil eye, ex-voto, an apotropaic device to protect us from politicians and advertising. It reminds us about suffering and love.

¤

How does a Greek poet, especially a young Greek poet, grapple with the burden of history and with the giants of both ancient and modern Greek poetry? When Derek Walcott was in Greece presenting his new book he told a group of reporters that “every time a Greek poet lifts a pen he lifts a column.” Seferis had nightmares about the Acropolis being sold off by an advertisement, that the columns were really tubes of toothpaste. In his own poem “Mythistorema,” he writes:

I woke with this marble head in my hands;

it exhausts my elbow and I don’t know where to put it down.

It was falling into the dream as I was coming out of the dream

so our life became one and it will be very difficult for it to separate again.(trans. Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard)

Yiannis Ritsos (1909-1990), one of Greece’s greatest, and perhaps still underrated, poets, spent the years after the Greek Civil War in the late 1940s and early 1950s, as well as the Junta years, exiled to barren islands as a political prisoner. Ritsos was tortured on numerous occasions and survived confinement and starvation, yet in spite of these conditions, he wrote poems, sometimes burying them in bottles in the prison yard to avoid detection. His insistence on writing poetry was in itself an act of resistance. His poem, “Epitaphios,” became an underground anthem for the oppressed. In a recent edition by Archipelago Press, a beautiful translation of his Diaries of Exile by Karen Emmerich and Edmund Keeley opens up this unique poetic memoir to an English audience. What is remarkable about these poems is that in spite of the critical situation, Ritsos managed to find moments of painfully accurate beauty in observation of his suffering, the mark of a true poet:

…Last night they took away our soccer ball

The playing field with the pennyroyal is deserted.

Only the wind butts the moon with its head.During dinner under the lamp

hands crumble the insides of bread

with a secret restrained impatience

as if winding an invisible enormous stopped watch.

This is what Greece has been doing for the last 2500 years: winding a stopped watch and taking bets as to which politician and which party and what percentage of civic indifference will rob the country blind again.

Photo: Matt Barret, Athens, Greece

Odysseas Elytis (1911-1996) is the third poet in the post-war “triumvirate” who managed to evoke a “Greek voice” internationally. He and Seferis both received Nobel Prizes, but Elytis approached his work through the influence of the French Surrealist. It was not until some years after the publication of his Axion Esti (It is Worthy), a long poem based on the ancient Byzantine Church liturgy, that his name became synonymous with the national consciousness and the love, sadness and frustrations of the Greek people. He wrote autobiographically, if somewhat cryptically, but the powerful images of the Greek landscape and the anthropomorphic forces of nature were things every Greek knew and recognized. The Axion Esti was again popularized by being set to music by Mikis Theodorakis, whose influence on the Greek public in the 1960s and 1970s was, and is, as great as all the poets mentioned. Here is an excerpt from Elytis’s “Genesis,” in the Axion Esti:

In the beginning, the light And the first hour

when lips still in clay

try out the things of the world

Green blood and bulbs golden in the earth

And the sea, so exquisite in her sleep, spread

unbleached gauze of sky

under the carob trees and the great upright palms

There alone I faced

the world

wailing loudly

(trans. Edmund Keeley and G. Savidis)

Greeks have always held onto their poets with particular tenacity and respect. No one knows where poetry will reside within this age of technology and attention deficit, but with Greece bankrupt and begging for alms, for once, it needs to look backward. W. H. Auden is famously misquoted as having simply said “poetry makes nothing happen” in his masterful poem, “In Memory of W. B. Yeats.” What he actually said is:

You were silly like us; your gift survived it all:

The parish of rich women, physical decay,

Yourself. Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry.

Now Ireland has her madness and her weather still,

For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives

In the valley of its making where executives

Would never want to tamper, flows on south

From ranches of isolation and the busy griefs,

Raw towns that we believe and die in; it survives,

A way of happening, a mouth.

If “Mad Greece” hurt us into poetry, it will survive in the valley of its making.

¤

Yes, it is exhausting being Greek. One has to remember so much, and the poet is in constant conflict with both the limits and the opportunity the historical context provides. But the love of Greece is about topos; it’s about language and landscape and the unforgiving, omniscient light of summer. Poets do not need to prove beauty; they just need to bring it to attention.

But how are Greek poets supposed to praise what has betrayed them? Greece is a country whose corruption manifests itself in the minutiae of everyday struggle: from tiny pensions slashed to pay off European debt, to cover-ups for politicians who sold the beachfronts for golf courses that don’t exist. How are the youth of Greece supposed to move out of their parents’ homes and stop living off their dead grandparents’ pensions, if their best other option is a 550 Euro a month minimum-wage job? This is a difficult question because it is age specific: the young have higher expectations, they have not known famine or war. The leftist radicals and anarchists are also involved in the capitalist model even if they refuse to admit it — they wear Converse and carry Macbooks. They tweet.

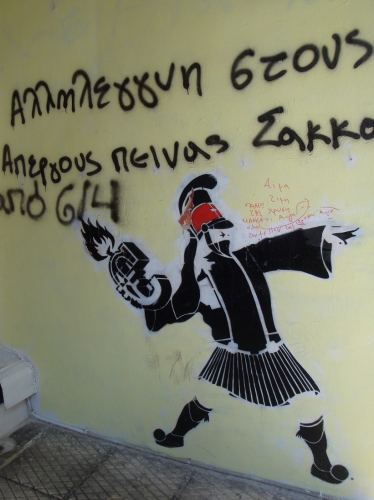

The economic situation in Greece is dire, and the only people who are being punished by these radical austerity measures are the poor, the blue-collar workers on fixed salaries, and the lower-middle class. Greeks on a traditional payroll cannot hide their income, so a tiny middle class, and a sea of poor overtaxed Greeks living hand-to-mouth, are now bankrolling the entire nation. Youth unemployment is above 50 percent, and regular unemployment is approaching 30 percent; cultural ministries are void, hospitals are understaffed, pharmacists are unpaid and not distributing medicine, uncollected garbage grows in street side mounds, and half of Athens’s once thriving small shops are boarded up and covered in graffiti. The illusory advances we made out of post-war Balkanism toward modern “Europeanism” are now dissolving. The cripples are back at the traffic lights and gypsy children beg at restaurant tables selling roses or halfheartedly fingering tuneless accordions. The sidewalks are broken, cars park on crosswalks, and for the first time in my life I’ve seen Greek pensioners furtively digging through garbage dumpsters at night. Greece’s reward for being “European” is anger, sadness, anxiety and suicide — so how are poets supposed to praise?

Photo: Matt Barret

Whenever I’m back in Athens, the first person I call is Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke (b. 1939). She has the uncanny knack for getting to the heart of every matter or crisis at hand — with incredible humor and dangerous wit. She is one of Greece’s foremost poets and translators, a truly electrifying presence in the Greek poetic canon, and in her deep friendships with other poets and writers. In addition to her own long list of books, she has translated Shakespeare, Pushkin, Heaney, Brodsky, and Walcott, among numerous others. When I stopped in to see her this time, she had just won the Greek National Prize for Poetry. I asked her how she felt about a poet’s love-hate reaction to Greece, and she replied with a line that she once mentioned to me in passing on a beach in Aegina, and that has now reentered her work as the ending of an unpublished prose poem:

It’s the same with my country. I was born here, raised here, grew. Everything here is difficult, uncertain, unplanned or badly planned. “I’m leaving,” says my cosmopolitan self, “I can’t take it anymore.” And suddenly the day breaks, another door opens. Light, light everywhere from all around, in the mind and in the soul. Broad-leafed light. Greece. “I’ll stay,” I say, “I’ll stay a little longer.”

But in the last poem of her prize-winning book, a darker conclusion sets in:

“Poetic Postscript”

Poems can no longer

be beautiful

because the truth has grown ugly.

Experience is now

poetry's only flesh

and as long as experience is enriched

so is poetry and might even strengthen.

My knees hurt,

and I can no longer bow to poetry,

I can only give her

my lived-in scars.

The epithets have wilted

and it’s only with my fantasies

that I can decorate poetry.

But, I will always serve her,

as long as she will have me of course,

because only she can make me forget a while

the closed horizon of my future.(trans. Stephanos Papadopoulos)

In another ironic twist, the $7000 check supposed to accompany her prize is apparently “on hold” — the government seems to have run out of money.

I recently spoke to Haris Vlavianos, a well-known Greek poet who edits Greece’s leading biannual poetry journal, Poetics, and he pointed out that while the crisis is causing deep distress politically and a general sense of malaise and hopelessness among the young, his last two issues of poetry featured major selections by a number of Greek poets under the age of 35. That said, things are not easy for young poets in Greece. They are virtually unable to make any money from a writing life; readings are unpaid, publication is unpaid, and contemporary poets are in constant conflict with the burden of history. In a recent article for Newsweek, Vlavianos reiterated a hopeful tone:

For an Athenian, however, life must go on. Despite the bleakness of the situation, with the International Monetary Fund and European bankers and speculators announcing in ever-increasing cynical, and sometimes vindictive, tones that the “day of reckoning” has finally arrived […] There is still some resilience and pride left. As a friend of mine told me a few days ago, “if we are heading toward the iceberg, let us at least drown in style.”

¤

Professor Karen Van Dyck at Columbia University, along with Professor Karen Emmerich (now at University of Oregon) and translator Peter Constantine have worked extremely hard to promote the work of younger Greek poets through their efforts as translators and as spokespeople for Greek Literature to an English-speaking audience. Dinos Siotis, a Greek poet who spent decades in Boston, now edits the magazine (De)kata, a kind of Paris Review for Greece, and he continues to draw crowds at hip cross-cultural events. Last year he held a reading event at the national library called “Crisis Poetry” featuring Nanos Valaoritis and Titos Patrikios, two major contemporary poets who lived through Greece’s tumultuous political past. Young poets who find them especially relevant in these difficult timesn admire them. Ianos Bookstore on Stadiou Street hosts packed evenings of poetry and music, for free, in a beautiful bar/event space above the store. The Hellenic American Union, the Athens Centre and the EKEVI National Book Centre have all been tireless advocates for poetry in Greece. Shockingly, as of January 2013, the National Book Centre was being shut down for lack of funds. In the United States, this would be the equivalent of the NEA Foundation closing.

Gavrielides Books, a well-known publisher with a focus on poetry has realized that publishers must adapt to the times and has renovated a beautiful neoclassical mansion as the new headquarters, added a café/bar, a garden patio, and an event space for readings, turning what could have been another stuffy publishing office into a vibrant arts center. This type of multi-use cultural facility is becoming more common, and young poets are using the benefits of social media to promote these “happenings” all over Greece. In spite of the distasteful system of publishers requiring many poets to pay for their own print run — a form of veiled self-publishing — slim new volumes continue to emerge, even if no one buys them. Copies are handed out to friends; readings pop up and though the wine is boxed no one seems to mind. Vassilis Rouvalis, a poet from Koroni, in the Peloponnese, is the editor of Poema (http://www.poema.gr/), a delightful and high-quality online magazine covering both new and older poets, as well as translated poets. In a country where arts funding is virtually nonexistent, his efforts to promote poets and poetry are truly a public service.

¤

In a country marked by austerity measures, it is important to bring attention to the veritable bounty of young poets writing today. These poets are publishing in international journals, reading at festivals in Europe, and generally broadening their poetic horizons so that you are just as likely to encounter e.e cummings, Pound, and Milton as you are Cafavy, Seferis, and Elytis. These are Greek poets absorbing foreign influences, or perhaps even immigrants themselves, both within and outside of Greece — this does not make them any less able to speak to the Greek population. Danae Siozou (b.1987) was raised in Germany, and later studied English Literature at the University of Athens. Constantine Hatzinikolaos (b.1974) was born in Athens but studied film and digital design in Paris. One of his poems, featured in the 9th edition of Poetics, is joyfully titled “My Mother is not Isabelle Huppert.” Katerina Iliopoulou (b.1967), an accomplished Greek poet who has translated Ted Hughes, Sylvia Plath, and Mina Loy, among others, is clearly as influenced by foreign literature as she is by Greeks and is interested in expanding her work into collaborations with film, performance art, and theater. Her award-winning first book, Mister T. has overtones of Zbigniew Herbert and John Berryman, even if unintentional, which reminds me of Cavafy and Fernando Pessoa, even if unusual. Poetry cares nothing for borders:

“Waking up”

Every day Mister T. wakes up inside a different person.

That is why he gets up very early.

Before dawn

He climbs the steps of the moments and he goes into the bathroom.

There he begins to peel away the scales of night.

The frozen streets, the bays and piers, the thick foliage and the loops of branches/ the indecipherable texts, the bloodthirsty virgins, the flocks of birds.Once he is completely naked

He lays his eyes on the mirror

The way someone hangs his coat on a hook.

But instead of eyes he has two fishes.

Being a man of immense patience,

He lets the fisheyes swim freely in the mirror.In those moments he experiences the purest dream:

The dream of being no one.

The most irredeemable solitude.

The pitch black crossword of the abyss.An event that endows his features

With the quality we refer to as “depth”.

Shortly thereafter, the eyes return to their place.

Between them and the mirror a certain relationship has now evolved.

Thus, they may recognize one another.(trans. K. Matsoukas)

Dimitris Allos (b. 1963) has published two collections, holds degrees in sociology, edited a Bulgarian literary magazine for many years, and also worked selling vegetables in Athens’s raucous open market. He happens to be married to Iana Boukova (b.1968), a highly accomplished Bulgarian poet and translator who writes and publishes in Greece. Allos translated his wife’s collection, The Minimal Garden, into Greek. Here is her poem, “Neighbors”:

First they come for a cup

of sugar for a cup of vinegar

for nothing

And you being well brought up

allow your kitchen to fill

with people and your days to shorten

as if winter has suddenly begun

Later all evening through the wall

you hear the muffled blows of bodies the dog’s

bark the ringing of the phone

which nobody answers

Your cigarettes pack up this night

you walk for miles in the room

and then in your dreams (having finally fallen asleep)

In the morning you see them refreshed they water

their flowers wave to you

go out in the open

casting a fourfold shadow

like a footballer’s

in the middle of the park.(trans. J. Dunne)

In the very lovely tradition of intergenerational poetic exchange, Allos writes a poem for Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke, who then translates it into English:

For Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke

-sole receiverI give you as a present

this beautiful bird

and its cage.(trans. K. Anghelaki-Rooke)

Yiannis Stigas (b. 1977) studied medicine and has published three collections to critical acclaim. In an excerpt from a poem titled “The Labyrinth’s Perfect Acoustics,” he writes:

IV.

I’m so eager for the world to end

that by the time I’ve written “flower”

it has already lost two petals

I don’t know if the light

is a trick of darkness

or the reverseI

can only torture butterflies

(none of them knows how to love me)(trs. Stephanos Papadopoulos)

He represents a generation of younger Greek poets who no longer define themselves by attempts at creating the generation of the 1930s, or attempting to emulate the lionized generation of the 1970s. Greece has changed, and the unified moral clarity held by the previous generations has been shaken. But poets will find their own pathways to describe it, and people will recognize their own images in the fragmentation.

And then there is Stamatis Polenakis (b.1970), a poet and playwright who manages to encompass all of these elements in his work. He is lyrical in the traditional modernist fashion, but his poems jump from musings on Russian literature to the heteronyms of Pessoa, the population exchanges in the 1920s, Heraclitus, Mayakovsky, and landscapes of snow. Like many younger Greek poets, he has moved beyond the narrow confines of nationality; losing those stereotypes is a kind of slow-release freedom. It is often those Greeks who leave Greece and then return that see it with the clearest, if most bitter, eyes.

When I go back home to Greece, which is very often these days, I stay in the house I grew up in. It’s the same stone house my grandfather built in 1925, the house he died in, the house my father died in, the house that was occupied by Italian Fascists, then Nazis, then communist rebels. It was the first house in the neighborhood to have water from a well my grandfather had dug, importing a windmill and a water pump in 1926 from Springfield, Ohio. The windmill and the pump are still there, rusting. For years developers have tried to convince my family to sell the land, tear down the house, and build a concrete monstrosity like the rest that now surround it. But none of us could do it. The house is a receptacle for memory; it holds our family history in its thick walls, just as the poets hold the memory of Greece in their verse. A poem from Polenakis’s recent book Odessa Steps seems like the perfect way to end this, as it represents, even if it didn’t intend to, the way every Greek feels right now:

“The Great Enigma”

Goodbye forever to this brief

age of freedom.

Farewell unforgettable days and glorious nights

and leaves scattered by the wind.

We were young, we hoped for nothing

and we waited for the morrow with the blind obstinacy

of the shipwrecked person who casts stones in the water.(trans. R. Pierce)

¤

LARB Contributor

Stephanos Papadopoulos was born in 1976 in North Carolina and raised in Paris and Athens. He is the author of several poetry collections: The Black Sea, Hôtel-Dieu, and Lost Days. He is also the editor and co-translator of Derek Walcott’s Selected Poems in Greek, a poet he was closely affiliated with for over 20 years. He was awarded a Civitella Ranieri Fellowship for The Black Sea and the 2014 Jeannette Haien Ballard Writer's Prize selected by Mark Strand, He was awarded a Lannan Foundation Fellowship residency in 2019. He lives between The Pacific Northwest and Athens, Greece.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The View from Bodrum

Herodotus would have had much to say about both the events that led to the tragic death of Aylan Kurdi, and the way it has been treated in the media.

“All I Have Is a Voice”: On Greece’s National Confusion

How is it possible, you might say, that an entire nation is befuddled?

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!