How to Love: Matthew Strohl and Rax King on Bad Movies

Nicholas Whittaker compares two recuperative, complementary accounts of loving bad objects.

By Nicholas WhittakerMarch 30, 2022

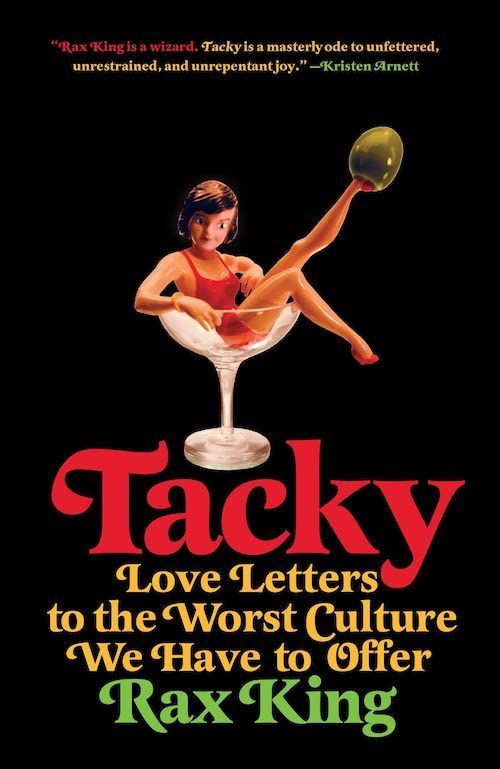

Tacky: Love Letters to the Worst Culture We Have to Offer by Rax King. Vintage. 208 pages.

Why It’s OK to Love Bad Movies by Matthew Strohl. Routledge. 218 pages.

IN HER BITING manifesto “Trash, Art, and the Movies,” patron saint of modern film criticism Pauline Kael argues that bad movies are essential to cinema because movies are mostly garbage. As she explains: “[I]t’s preposterously egocentric to call anything we enjoy art — as if we could not be entertained by it if it were not.” Movies entertain us, tapping pleasure buttons with uncanny precision, and if that is all they have to offer us, why can’t that be enough? (Her examples include Wild in the Streets or The Thomas Crown Affair; 2001: A Space Odyssey, on the other hand, is neither art nor entertainment, by her lights.)

This ethos has only spread in recent years. Tommy Wiseau has become, bizarrely, a household name. It is cool to like bad movies these days, usually with an air of mocking irony or guilty pleasure, sometimes with sheer unabashed earnestness. Philosopher and bad movie lover Matthew Strohl’s Why It’s OK to Love Bad Movies (Routledge, 2021), part of Routledge’s Why It’s OK series, is the manifesto, and corrective, this movement needs. It challenges, as much as it defends, those of us who claim to love Nicolas Cage and The Room and Troll 2 and Twilight. Strohl doesn’t just want us to like these movies, but to care about them as well.

For Kael, bad movie love is a blessed, unabashedly crass form of hedonism, and Strohl is a hedonist, too; he loves bad movies because they bring him joy. The six chapters of Why It’s OK to Love Bad Movies, rich with close film analysis and abnormally accessible philosophical argumentation, convincingly show that these movies are wonderful. Indeed, the book is almost unbearable to read, as any writing on film worth its salt ought to be. All one wants to do, at virtually every page, is put it down and watch Batman & Robin.

But Strohl’s love is compelling and infectious precisely because it’s not just concerned with pleasure. Rather, it is built, like all real love ought to be, on an ethics of kindness. Strohl happily admits that bad movies are bad. The last thing he wants to do is pretend, as he puts it, that Citizen Kane and Plan 9 from Outer Space are the same kind of movie. Indeed, to do so would be to work against, rather than for, bad movie love. Strohl loves Citizen Kane because it is good, and he loves Plan 9 because it is bad.

Here lies the book’s major philosophical intervention. When Strohl calls Plan 9 “bad,” he is not making a judgment call about its value, about whether it is worth watching, even about whether it offers us pleasure. Like Kael, he sees artistic goodness as distinct from the question of ultimate worth; wonderful movies don’t have to be good art. Rather, Strohl suggests that, when the critical establishment (and even a discerning viewer) deems a movie “good,” or praises it as cinematic “art,” what this really means is that the work satisfies cinematic convention: it looks, sounds, moves, and feels the way a movie is supposed to, according to established norms of filmmaking and taste. Conventions are not intrinsically bad; the convention that an actor uses an accurate accent often results in a more compelling performance. But conventions can limit. Those critics who populate the aggregate sites and assemble the Oscar short-lists too often insist that the only way for a movie to be pleasurable is for it to satisfy these norms.

Bad movies ignore the scriptures of Rotten Tomatoes. They break conventions, rather than playing by their rules. Strohl’s critical eye is sharp as well as generous, attentive to the myriad of real aesthetic riches bad movies offer. Bad movies break rules to find out what exciting, interesting kinds of beauty exist outside of the bounds of convention. They dare to imagine what aesthetic pleasures a bad accent might result in. Strohl argues that there is rarely any real difference between the bad movie and the avant-garde masterpiece. Both push past accepted norms to reveal new possibilities of human expression and appreciation.

But a crucial component of Strohl’s argument is that even the most affectionate ridicule — the mode of appreciation epitomized by Mystery Science Theater 3000 and Nicolas Cage memes — papers over this radical strain of aesthetic anarchism. Strohl devotes an entire chapter to Cage himself, not just defending the Wicker Man star from his haters, but from those who mock him and call it love. We lose something when we reduce Cage to moments of thrilling grotesquery, particularly when they are taken out of context. We lose something when, in Strohl’s words, we substitute ridicule for love. For 40 pages, Strohl offers one of the most careful career retrospectives Cage has ever received (joining the recent cluster of generous work on Cage). What seems — when reduced to YouTube reels of “Best Cage Freakouts” — like badness is the work of a bravely experimental performer. Cage’s ambitions are not simply to “scream really loud,” but, rather, to “translate the sonic dissonance of avant-garde composer Karlheinz Stockhausen into human speech” (in the “crazy Cage” mainstay Rage) or “collage and recontextualize archaic Expressionist performance stylings into the ’80s rom-com form” (in, believe it or not, Moonstruck). Cage uses movies as a laboratory for human expression — to poke at, think through, and reimagine the ways in which the body moves, the voice sounds, the eyes dart. If this is wrong, who wants to be right?

It isn’t just that Cage is good at what he’s trying to do, but that he’s trying to do something at all, that — yes, it sounds trite, but most things that matter do — he has goals, desires, reasons for doing what he does. Strohl never lectures on this point; his ethics are never stodgy, being largely implicit. But it is there, steeping the entire book in a deep sense of care.

Throughout the book, Strohl almost obsessively draws attention to the human beings behind bad movies. He gives special place to their own words, their life histories, and their dreams. In doing so, Strohl seeks to uncover new genuinely aesthetic features that become more pressing when we acknowledge the fact that these movies do not emerge from the ether, but from the hearts and hands of people. The Cage exploration illustrates this particularly well, though his generosity extends to the people who worked on Plan 9, Troll 2, and Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning. What results is not a simplistic ethics, but a rich aesthetic, one that sees “being human” and “being glorious” as entangled. Human beings, in all our rapacious strivings and failings, can’t be summed up by social conventions. We’re bigger than them; shouldn’t our movies be?

Strohl asks: What if we saw the earnest care and passion that fuels the engines of so many bad films as an opportunity for love? It is no wonder that he cites Kael, and her own defense of trash, repeatedly. Kael, more than most, built her film criticism on a wry, unromantic humanism. Her disinterest in films as art was equaled by her interest in films as human (and thus sad, odd, and sometimes glorious) — flashes of brief significance buoyed by a crooked smile, a cracked croon, a single instant of familiar absurdity. Strohl sees trash as rich with such flashes. His analytical precision, zealous passion, and overwhelming generosity make Why It’s OK To Love Bad Movies genuinely indispensable.

¤

Rax King, too, is obsessed with bad movies. And not just movies: her recent book, Tacky: Love Letters to the Worst Culture We Have to Offer, is headily indiscriminate in its adoration for the titular object: Josie and the Pussycats jostles against America’s Next Top Model and the Cheesecake Factory.

Unlike Why It’s OK To Love Bad Movies, King’s book is memoir peppered with theory; Strohl’s work, by contrast, is theory peppered with memoir. Each of her 14 essays is, on its face, about a particular tacky cultural item. (King prefers “tacky” to “trashy.”) But those artifacts spend most of the time as scenery. They form the backdrop of King’s life, emerging into the spotlight only in precisely selected moments. What ultimately matters, for King, is not (just) the garbage itself, but the person who loves them. As such, no single movie or musician, or shitty perfume, is taken in isolation; rather, King carefully, lovingly articulates what they mean to her, the particular place they hold in her life. The essay on Jersey Shore is an essay about King’s late father, written with an ache that’s hard to shake off; her discussion of Sex and the City slides back and forth between her relationship with a dear friend. She pairs Sims with her abusive ex-husband. Sometimes, the whiplash is jarring, frequently almost surreal. Yet, it is never forced; the juxtapositions make perfect sense.

That is, after all, what King is after: to connect, as does Strohl, the tacky and the human. Strohl’s focus is one half of the equation, King’s the other. Strohl reminds us that bad movies themselves — and the human beings who create them — should be treated with care; King reminds us that we, the human beings whose lives are formed by and around tacky objects, deserve care, too.

Take the first essay (a highlight of the book), which details King’s lifelong love affair with the critically reviled pop-rock band Creed. The essay seems, from a distance, to join Strohl in his quest: to defend downtrodden art on the basis of its humanity. King argues that Creed’s music may not be artistically good, but that it is human, and that sometimes being human is better than being good. Scott Stapp, the band’s frontman and cultural punching bag, made music to express pain and sees no reason to erect space between that pain and its artistic expression. He simply emoted with an ugly and crass grandeur. Fine, King argues, call it bad. But that badness becomes an excuse to ignore the emotional reality of Stapp’s life, and the way his music — poor as it may be — grapples with that pain. To respond with flat dismissal and contempt, then, is little short of cruel.

But ultimately, it is not Creed, Jersey Shore, or Guy Fieri on trial here: it is the author herself. King’s autobiographical tangents sketch a deeply familiar, and deeply sad, narrative of a child slowly learning that the world quickly turns its mocking fury from bad artists to their vulnerable fans. The first thing King ever hears called tacky is not a thing at all, but a person: her grandmother. It’s not just bad movies and TV and pathetic 2000s boy-rock that needs a champion, but also the people who love them.

By offering herself up as a kind of case study, aimed at the project of humanizing tacky people, King humanizes us all, because who among us has successfully resisted the siren song of trash? What King reveals is that our failure to resist reveals the loveliness of our flawed, feeble, and sometimes glorious humanness. We do not consume art as algorithms, but as humans, as tangled knots of often contradictory, rarely neat, needs and desires, as too big, too unwieldy sums of histories and impulses and relationships that stretch infinitely forward and infinitely back. Why pretend otherwise? Why pretend that it’s not the case that Sex and the City first appealed to teenage King because it sounded like a porn title, and because she wanted to impress her friend and crush, and because it went on to play a central role in their relationship, and in King’s relationship with sex? Why not admit that Hot Topic arrived in King’s life exactly when she needed it, ostracized at school and in desperate need of a new set of values to reorient her sense of self-worth? King finds that pretension self-abnegating, and she sharply makes the case that you should too.

Crucially, King (like Kael) is not a romantic; or, when she is, she treats it as a kind of tackiness. For her, tackiness is synonymous with emotional overload. As such, it may be compelling, thrilling, and necessary, but it is rarely pretty, often messy. Tackiness frequently leads King to behaviors or feelings she (often retrospectively) knows to be misguided, such as when she develops a sense of snobbish superiority toward normies and posers upon discovering Hot Topic as a kid. These moments of overload, of messy, not-quite-right emotions, often frustrated me, which perhaps is King’s point.

In those moments of frustration, what I wanted, as I suspect many readers will, was to see King transform tackiness into something decidedly untacky: something sophisticated, ethically justified, admirable — something right. Only then would it — and King, and myself — deserve kindness. But that would miss the point. Tackiness deserves kindness precisely because it is always unsophisticated, usually ugly, and frequently wrong (according to conventions of human behavior and expression). The work is not to lionize us in our tackiness but to humanize us, to run to, rather than away from, emotional overload. That excess of love (in all its fucked-up forms) is a necessary consequence of living. Tacky falls flat when read as a full-throated defense of tackiness as an objective, and objectively good, feature of art. That’s not how King wants it to be read. Read it, instead, as a love letter to tacky people, exactly as they (we) are.

¤

Together, Strohl and King imagine a new future for transgressive cinematic tastes, one that might be called a revival of humanism. They seek to build — in Strohl’s words — “better practices of engagement” with trash, better ways of relating to and doing things with them, formed on foundations of care, of generosity and kindness directed at the profoundly human heart of trash. If we’re to love bad movies, rather than mock them and call it love, those foundations are essential.

But there’s a way to do care wrong, and King sometimes makes this misstep. While discussing the gleefully tacky 2001 film Josie and the Pussycats, she turns to Susan Sontag’s seminal essay “Against Interpretation.” The essay ends with Sontag’s calling card: “In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art.” “Hermeneutics,” King argues, referring to the act of interpretation, means “dissect[ing] art so that no piece of art need remain a mystery to its viewer.” Erotics, on the other hand, is that pre-reflective impulse of sheer magnetism, the pleasure button. Sontag’s declaration is interpreted as an unequivocal abandonment of interpretation, in favor of “pure feeling,” and this contrast juxtaposition becomes King’s rallying cry for tackiness. Tacky things are “perfect,” a precise term by which King refers to the resistance to interpretation. A good pop song, a good chicken tender, Josie and the Pussycats — all these are perfect, for King, because they speak wholly for themselves, as themselves. To analyze these objects would be an attempt to pin down the right way to experience the perfect thing and the right way to respond to it, according to conventions of taste. Tackiness can’t survive interpretation, and it shouldn’t have to.

This conclusion is worrisome, not least because it would entail the death of politics. King, for example, treats America’s Next Top Model as a tacky work that she deeply loves. Does this mean it is perfect? And does this mean that it escapes politics, politics only recognizable when we interpret? What am I to do with the extended history of antiblackness, transphobia, classism, and good old-fashioned misogyny wrapped through ANTM’s DNA? What am I to do with the fact of Tyra Banks’s quite obvious abuse? What am I to do with the tunnels of body dysphoria, self-loathing, and gender panic ANTM has sent me down as I’ve grown up with it?

What am I to do with the fact that I love it, too?

Therein lies not only the rub, but the solution. Because what King is missing here isn’t a concern with politics, but the willingness to imagine an interpretation that is erotic, that is steeped in love. It is possible to imagine a genuinely erotic hermeneutics, because Sontag herself does. In the same essay, she makes a crucial clarification:

Thus, interpretation is not (as most people assume) an absolute value, a gesture of mind situated in some timeless realm of capabilities. Interpretation must itself be evaluated, within a historical view of human consciousness. In some cultural contexts, interpretation is a liberating act. […] In other cultural contexts, it is reactionary, impertinent, cowardly, stifling.

“Against Interpretation” is the eulogy for a particular kind of interpretation. But in the humanist future Strohl and King imagine, would interpretation be “reactionary, impertinent, cowardly, stifling”? Are we not free to develop new forms of interpretation, in service of and birthed by new ways of relating to art?

King’s resistance to this imagination betrays, rather than protects, the deep humanism at the heart of her and Strohl’s theories of bad taste. Strohl demonstrates the beauty of erotic interpretation by investigating these films, revealing things about them, seeking to understand them — not on the terms of conventions, but on their own. He imagines bad movie love with the metaphor of conversation. For him, loving bad movies is not a demand to silence, but a chance to say more, and say it with feeling; to think and wonder and appreciate, all loudly and with great excitement. Rather than an ethics and aesthetic that mandates or lectures, one that talks to or for, Strohl imagines a way to love best described as talking with. What if interpretation was not a mandate but an invitation? What if my challenge to ANTM was an act of love, by which I mean it was not a command but an inquiry, one that participates in the practice of loving ANTM rather than seeking to disrupt it?

After all, love is not silent, not Strohl’s and not King’s. Perhaps the deepest betrayal she performs here is that of her own resistance to interpretation, a betrayal played out over 14 essays filled with loving, intricate, and erotic interpretation. The greatest flaw of Tacky lies in its self-diagnosis. It is a testament, like Why It’s OK To Love Bad Movies, not to the death of criticism but the birth of a new kind of hermeneutics. What trash deserves is not our silence or our scorn but a cacophony of love: ribald, unhinged, earnest. The pursuit of understanding, indistinguishable from a celebration, overwhelmed by feeling — these are the sounds of being human.

¤

Nicholas Whittaker is a doctoral candidate in philosophy at the City University of New York, Graduate Center. Their writings on art, love, and blackness can be found in The Point, The Drift, Holo Magazine, Aesthetics for Birds, and elsewhere. They are located in Queens, New York.

LARB Contributor

Nicholas Whittaker is a doctoral candidate in philosophy at the City University of New York, Graduate Center. Their writings on art, love, and blackness can be found in The Point, The Drift, Holo Magazine, Aesthetics for Birds, and elsewhere. They are located in Queens, New York.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Beloved Objects: Two Books on Queer Fandom

Charles O’Malley compares two recent memoirs that explore queer attachments to and identification with popular culture.

Against Identification: The Abject Camp of “The Witches” (1990)

Charles Ramsay McCrory explores the intertwining affects of identification, attraction, and abjections in the 1990 children’s horror film, “The...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!