How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Novel

Tom Comitta reflects on the process of growing to love, and eventually write, novels.

By Tom ComittaMarch 25, 2023

The Nature Book by Tom Comitta. Coffee House Press. 272 pages.

I USED TO BE the kind of poet who sang the Patriot Act to surveillance cameras. Or read the entirety of a Yahoo message board verbatim to a small crowd. Or invited everyone in a bookstore to sing from books on the shelves. At every reading, I would show up with something new, feeling, like an installation artist, that a reading should respond directly to its context. When I actually penned something myself, I wrote fast and often intentionally bad. Everything I did attempted to push the formal envelope of what could be considered a poem.

I was also the kind of poet who despised short stories and novels. I valued writing that directly engaged with the problems of language—how it limits our perception of the world, its tendency to normalize thought and behavior, etc.—and found most fiction to supplant this engagement with immersive stories designed to distract the reader from such problems. And I wasn’t alone. In the Bay Area poetry community, I found others who questioned fiction’s artifices. What was this impulse to tell tall tales? we wondered. Why should readers invest themselves in these made-up characters and their difficulties? And why was it that nearly every novel required cliffhangers, plot twists, a hero’s journey, and so on? We saw fiction as big business, with many of the novelists we knew salivating over the unlikely prospect of a large advance and movie option. It seemed that the novel was simply “content” waiting to be monetized and transformed into a different medium entirely.

I’ll admit that I hadn’t given fiction enough of a chance at the time. Sure, I’d read novels in and outside of school, but I had yet to find the works that pushed against the tropes that my community and I recognized. I might never have found these works had my friend, the artist Kota Ezawa, not invited me to give a reading during his exhibition at San Francisco’s Center for the Book in 2012.

In keeping with my philosophy that a text should respond to its context, for this reading, I wanted to respond to Kota’s work. So, I went to another exhibition of his that had just opened across town, The Curse of Dimensionality. In the back room of the show, I found one of the most interesting animations I’d ever seen.

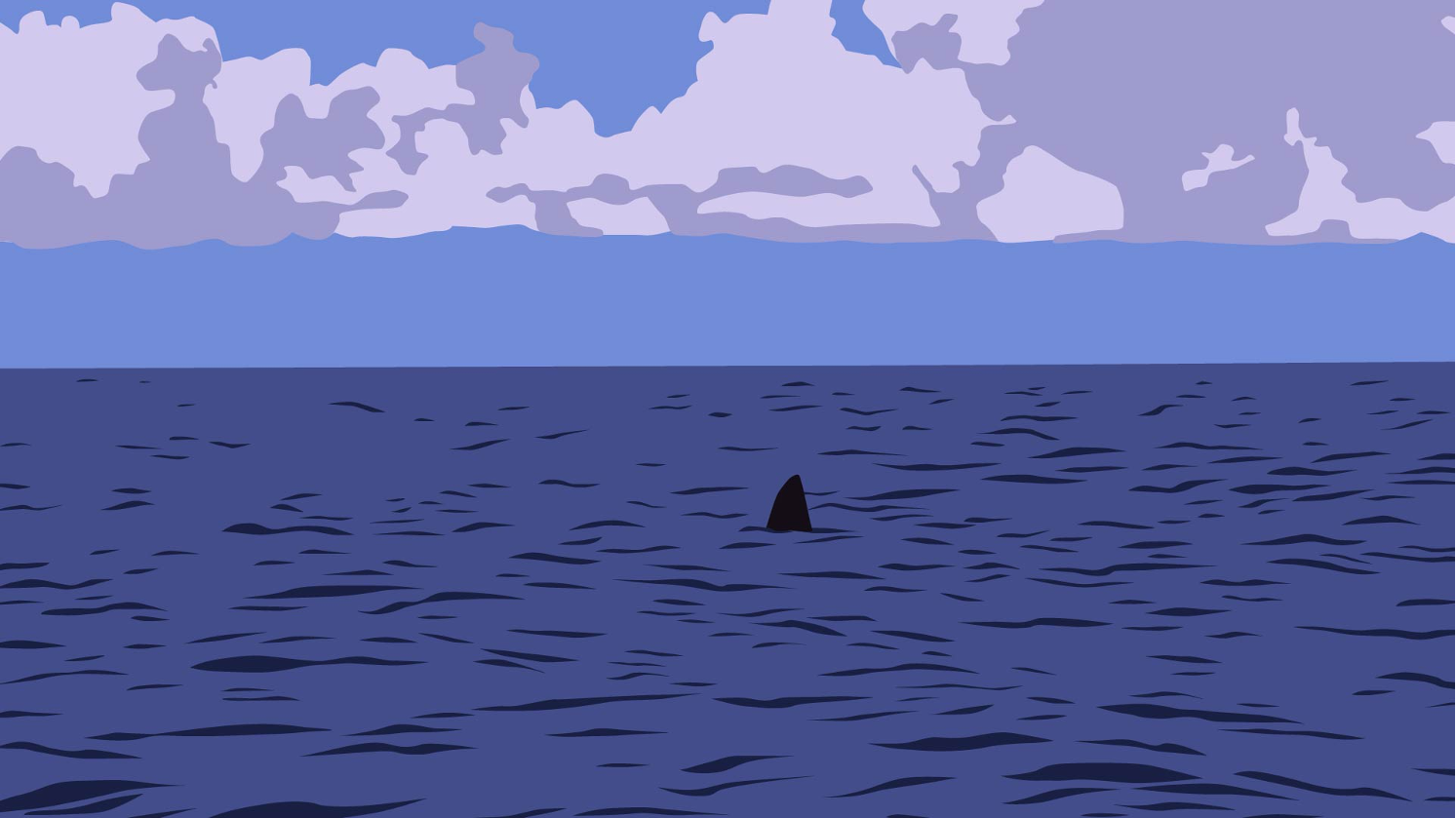

Kota’s short video City of Nature (2011) consists entirely of rotoscoped nature shots from feature-length movies: the river of Fitzcarraldo (1982) cuts to the river of Deliverance (1972), which cuts to the river of Rambo: First Blood (1982), which flows to the sea of Swept Away (1974), which cuts to the sea of The Old Man and the Sea (1958), and so on. Some of the shots feature animals: in one instance, a squirrel runs through trees, and two dogs sit chewing in the dawn light. Others are characterless: a pan of mountains in a misty haze, still shots of leaves scattered on the ground. In a few instances, Kota’s rotoscope effect turns these realistic nature shots into total abstraction. Clouds, now flattened and reduced to solid colors, look like blobby amoebas shifting over a slide.

Most of Kota’s prior video work had examined depictions of violence in visual media. Surprised by this seemingly tame new video—in City of Nature, the only hint of danger is a cartoonish shark fin poking above the water for a few seconds—but finding clear echoes of Kota’s past work in his rotoscope technique, I wondered if this new film pointed to something pernicious about the process of framing life and flattening it into images. I wondered what a similar literary procedure might reveal about writing, language, and our relationship to nature.

The next day, I went to the San Francisco Public Library and went straight to the classics, searching for nature descriptions in novels by authors such as Virginia Woolf and Charles Dickens, George Eliot and Willa Cather. I must have spent five hours going through books and photocopying passages. Back at home, I spread the photocopies across my living room floor and tried to figure out how to turn them into some kind of narrative. After spending a few days studying the photocopied nature descriptions and meditating on the pacing of Kota’s video, which moved smoothly from one shot to another, teasing the impression that it had all been one movie to start with, I wrote a text that existed somewhere between a poem and a short story.

The night of Kota’s artist talk, I read my strange piece to a room of gallerists and art goers. Everyone clapped on cue, but it was hard to tell what they thought of it. My friend and former teacher, novelist Kevin Killian, gave me and my then-girlfriend a ride home. As we were pulling up to our apartment, Kevin said, in a playful tone, “I liked your post-writing.”

There was something in that term “post-writing,” the combination of light sarcasm and praise, that stuck with me. He never explained what he meant, so I had to speculate. Did post-writing refer to what you create after there is nothing more to say? Did it mean simply a kind of writing that cannibalizes other texts, as I had done, supplanting invention for something new entirely?

After a few days mulling over the potential of what I’d written, surrounded by the fragments of photocopied nature descriptions still scattered around my apartment, something clicked. Oh fuck, I thought. That short text I’d written wasn’t the finished piece. It had to be longer, more expansive; it had to take the form of the material it was drawing from. It had to become a novel—one made entirely out of nature descriptions.

Over the next two years, I tried to write such a novel. I started one version where each paragraph contained language from a different novel. I tried a second version where each chapter drew from a different novel and each title of these sourced novels referred only to nature, like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves (1931), Iris Murdoch’s The Sea, the Sea (1978), and Aldous Huxley’s The Island (1962). In keeping with my interest in tight literary constraints, this second version also attempted to fully remove “the human” from the source material, going so far as to exclude words like “banks,” as in the land bordering a river, because of their linguistic connection to financial institutions. This process meant that writing the first 2,500 words took me three months.

Eventually, I gave up. The project was too difficult, and the result was dull: the tension in trying to strip “the human” from language—a fundamentally human material—was producing a flat narrative. And at the rate I was going, I calculated that I wouldn’t finish the book until I was 70. At the time, I was only 29.

Attempting to come to terms with quitting, I wondered if the concept itself was enough. Maybe I could just say I was writing the book, and the idea would suffice? Borges said as much: “Writing long books is a laborious and impoverishing act of foolishness: expanding in five hundred pages an idea that could be perfectly explained in a few minutes. A better procedure is to pretend that those books already exist and to offer a summary, a commentary.”

Not long into abandoning what I had been calling City of Nature or “my nature book” or “the nature book I’m writing,” I started dating Medaya Ocher, then a fiction editor at Los Angeles Review of Books and English PhD candidate, who would later become my wife. She quickly elucidated how wonderful novels could be, turning me on to contemporary works like Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick (1997) and Tom McCarthy’s Remainder (2005), which showed me that novels could push against and even transcend some of the tropes that I was allergic to.

Remainder seemed to operate somewhere between conceptual art object and narrative, turning repetition and the act of simulating reality into the subject of the novel itself. I Love Dick’s blend of an antiquated form (the epistolary novel), autofiction, and art criticism showed me that a novel could be an act of cultural criticism. I felt addicted to Kraus’s sharp, gossipy writing, while also skeptical of these addictive qualities. Was reading this book like binge-watching reality television? In starting to read the right books, I found that I could maintain a healthy dose of skepticism while still loving the form.

I also started to read early experimental prose. In The Arabian Nights (the Husain Haddawy translation), I loved losing myself in the labyrinth of nested stories. Moby-Dick (1851) blew me away with its formal fireworks, but it was the extracts that proceed the novel that shocked me. Before the novel begins, Melville placed a literary supercut, or a text made entirely of quotations, that oddly resonated with my nature novel idea. Across 13 pages, Melville collected and collated 82 descriptions of whales in chronological order from Genesis to Shakespeare to Hawthorne. I was amazed and thrilled to find a work from 1851 employing basically the same method I’d arrived at.

In the middle of my novel education, I came across an essay by video artist and archivist Rick Prelinger. Fashioned as a kind of artist statement, the text described Prelinger’s interest in incorporating longer segments of found material into his work (as opposed to most collage videos, which juxtapose short clips in rapid succession). For Prelinger, longer takes allow his audience to become co-researchers, rather than simply passive viewers; they also provide more time for found material to sink in, revealing things that might be missed under a heavier editorial hand.

In my previous attempt at writing my nature novel, I was so strict in my efforts to excise the human that almost every sentence was a cut-up of between two and five other sentences. With Prelinger’s tip, I wondered if including full sentences and even strings of sentences from my source material would lead to a more interesting text and that would allow the sources to speak more fully for themselves, expressing the full range of their messy relationship to nature.

This seemed important because almost all nature descriptions are actually about people, often positioned at intense, emotional moments and designed to amplify human drama. Authors regularly assign human traits to animals (“the Kingdom of Bugs,” in David Foster Wallace’s 1996 novel Infinite Jest) or objects (“the ground sobbed,” in D. H. Lawrence’s The White Peacock, from 1911). Pathetic fallacy and pareidolia, or the tendency to see the human in nature, are everywhere. It’s this strange relationship between the natural and the human that makes nature descriptions interesting.

So, I got back to work. For the next year, I gathered as many nature descriptions as I could find. I scanned through hundreds of .txt and .epub files from Project Gutenberg and other online sources, copying and pasting paragraphs into a single document. After each entry, I’d add a code like “(WHB)” for Wuthering Heights (1847) by Emily Brontë so I could easily identify it later. By the end of that year, I had gathered 1,500 pages of nature descriptions, and had started to read novels on a regular basis.

The year’s end also coincided with the beginning of my residency at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts in Omaha, Nebraska. This was my first residency, and, with the help of a generously large studio and a dozen tables, I had a massive amount of writing space. I printed out the 1,500 pages of nature descriptions, cut them up, and spent a week sorting the fragments of language into groups.

I quickly found that nature descriptions fall into two categories that I’ll call macropatterns and micropatterns. Macropatterns deal with season and setting: the four seasons, oceans, islands, jungle islands, jungles, outer space, prairies or grasslands, mountain ranges, and deserts. These macropatterns basically served as the structure of The Nature Book. Micropatterns, on the other hand, exist inside of each of these seasons or geographies and deal with the minutiae of life: different times of day, different weather patterns like jolly, sunny language; gloomy, rainy language; or raging, stormy language, as well as different animals specific to each macropattern.

I grouped each macropattern on a different table. There was a winter table, a desert table, an outer space table, and so on. Then I went through each table’s macropattern and sorted the language into smaller piles, or micropatterns. With each pattern laid out, I went to work grouping language from each table into a separate narrative. Once all micropatterns were used up and each macropattern seemed exhausted, I worked to connect these separate narratives into a novel-length story.

This process took a few paragraphs to describe but required three months to complete. After writing a first draft, I spent the next three years writing seven more drafts, filling in the gaps—draft one didn’t have nearly enough winter or autumn descriptions, for instance—and building out the narrative into the novel that would become The Nature Book. I spent one more month at another residency, but for the rest of the time, I mostly worked in a small rented office. For four nights a week, six hours each night, I sat there stringing scraps of text together.

By the time I finished The Nature Book in 2019, I was totally hooked on novels. I had fallen in love with the Argentine novella tradition—started by people like Silvina Ocampo and Adolfo Bioy Casares and picked up by César Aira and Samanta Schweblin—and its ability to, in so few pages, throw my brain into a blender. I became a sci-fi junkie, huffing down books by Samuel R. Delany and Philip K. Dick, relishing the skewed realities formed from the interplay between their texts and my mind’s interpretation, realities infinitely more complex and pleasureful than any sci-fi movie could produce. I even fell in love with crime and detective fiction—genres that rely heavily on the kinds of tropes I had detested—delighting in the ways that authors like Jean-Patrick Manchette and Ryū Murakami playfully rearrange and invert these tropes.

I am now a fiction writer and can’t see myself writing a poem ever again. I spent 2021 composing a public opinion poll measuring the literary tastes of the United States—everything from favorite genre to setting to verb tense—then spent 2022 turning the poll results into two books: one with all the desired aspects, The Most Wanted Novel, and another with all those that were rejected, The Most Unwanted Novel. I now read at least five novels a month and am plugged into my Libby audiobook app like it’s an IV drip.

Looking back, it’s clear that, while many of my previous fiction complaints were valid, I simply hadn’t read enough novels. There are as many ways to write a novel as there are authors, and the tropes and traditions are simply waiting to be rethought, rearranged, and made our own.

¤

¤

Featured image: Still from Kota Ezawa, City of Nature (2011), video, 3:55. Courtesy of the artist.

LARB Contributor

Tom Comitta is the author of The Nature Book (Coffee House Press). Their fiction and essays have appeared in WIRED, Lit Hub, Electric Literature, the Los Angeles Review of Books, The Kenyon Review, BOMB, and BAX: Best American Experimental Writing 2020. They live in Brooklyn.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Tight Wires: On Sandra Simonds’s “Assia”

Kristin Grogan reviews Sandra Simonds’ “Assia.”

Viruses on Film: From the Pandemic Procedural to the Lockdown Comedy to the Activist Documentary

Steven W. Thrasher surveys the onscreen evolution of viruses in the wake of our collective experience with COVID-19.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!