Horror Fiction for People Who Don’t Like Horror Fiction

Tony Fonseca reviews Ramsey Campbell’s new horror trilogy, The Three Births of Daoloth.

By Tony FonsecaSeptember 7, 2019

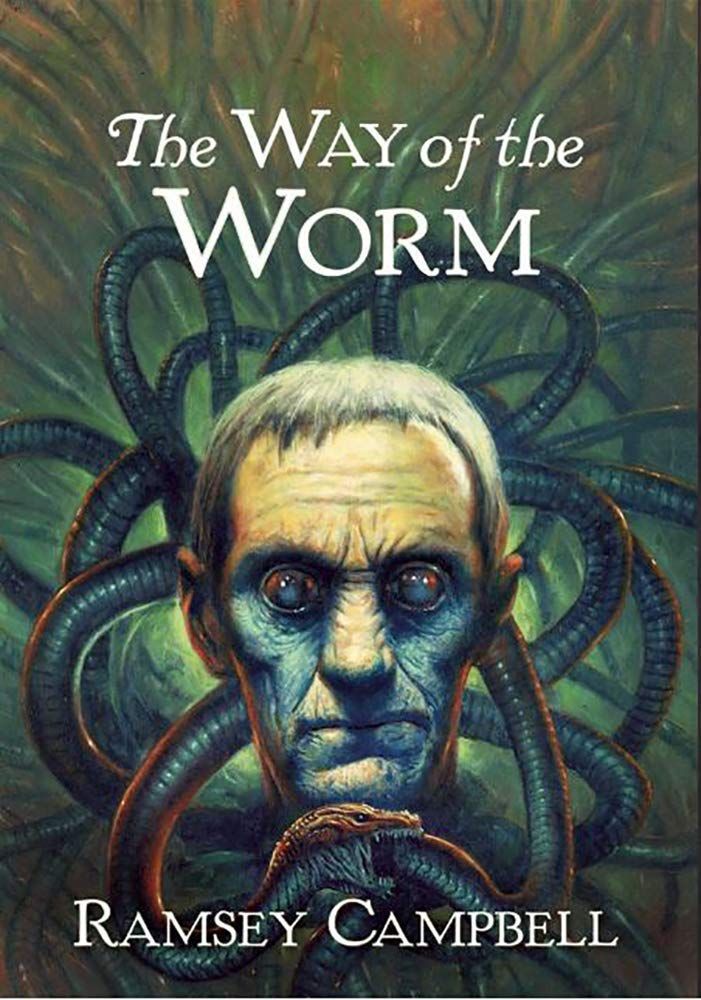

The Way of the Worm by Ramsey Campbell. PS Publishing. 275 pages.

RAMSEY CAMPBELL IS ONE of the most respected authors of weird and dark fiction in the world. Born in 1946, he began reading Lovecraft at the age of eight and began writing when only 11. As a teen, he submitted Ghostly Tales, a self-illustrated collection of 16 stories and a poem, to a reputable publisher, under the name John R. Campbell. Although the stories were rejected because of their genre, the publisher encouraged Campbell to keep writing (the author’s juvenilia was eventually published in 1987, as a special issue of Crypt of Cthulhu magazine). In 1961, Campbell submitted a story to Arkham House’s iconic author/publisher August Derleth. That story, “The Church in High Street,” appeared in the anthology Dark Mind, Dark Heart (1962), edited by Derleth, under the pseudonym J. Ramsey Campbell. It was Campbell’s first professional publication.

Campbell’s first published book was the Lovecraft-tinged The Inhabitant of the Lake and Less Welcome Tenants (1964), published by Arkham House when he was 18. His collection Demons by Daylight (1973) brought attention to his distinctive style and thematic concerns, and eventually led to a second Arkham House collection, The Height of the Scream (1976). That same year, he published his first novel, The Doll Who Ate His Mother. His second novel, The Face that Must Die (1979), explored dark psychological themes of madness and alienation — themes he would return to throughout his career. He received his first World Fantasy Award in 1978 for the story “The Chimney,” his second in 1980 for “Mackintosh Willy.” His 1980s novels and novellas — The Parasite (1980), The Nameless (1981), Incarnate (1983), The Claw (1983), Obsession (1985), The Hungry Moon (1986), The Influence (1988), Ancient Images (1989), Midnight Sun (1990), and the semi-comic Needing Ghosts (1990) — displayed a newfound interest in switching between the horror, dark fantasy, thriller, and crime genres.

Campbell hit his stride in the 1990s, publishing his first dark comedy, The Count of Eleven (1991), followed by The Long Lost (1993) and the three novels Campbell fans line up behind when they want to argue for his mastery: The One Safe Place (1995), The House on Nazareth Hill (1996), and The Last Voice They Hear (1998). Campbell has remained prolific, his more recent output including Silent Children (2000), Pact of the Fathers (2001), The Darkest Part of the Woods (2003), Secret Stories (2005), The Grin of the Dark (2007), Thieving Fear (2008), Creatures of the Pool (2009), The Seven Days of Cain (2010), Ghosts Know (2011), The Kind Folk (2012), Think Yourself Lucky (2014), and Thirteen Days by Sunset Beach (2015). Never one to rest on his laurels, he has recently (and incredibly quickly) completed his Three Births of Daoloth trilogy: The Searching Dead (2016), Born to the Dark (2017), and The Way of the Worm (2018). Word has it that yet another novel, The Wise Friend, is due to be published in autumn 2019.

One of Campbell’s earliest creations was the fictional city of Brichester (of the fictional Severn Valley), around which he constructed an elaborate mythos. He recently returned to the Brichester Mythos in the novella The Last Revelation of Gla’aki (2013). The Three Births of Daoloth trilogy (a.k.a. The Brichester Trilogy, all three titles released by PS Publishing) further develops the cosmic horrors he invented as a young man in The Inhabitant of the Lake. In a 2016 interview with psychology professor and horror author Gary Fry, Campbell explained his motivation for the trilogy: he wanted not only to update the Brichester mythos but also to perfect it, correcting the small mistakes he had made as a young writer. He conceived of the trilogy as a unit, so the series is tightly knit and the vision consistent, even as the story and characters evolve over 60 years. The trilogy is a nod to some of Campbell’s other early influences, such as Arthur Machen, but it was Lovecraft, according to Campbell, who provided the “crucial focus.” In the trilogy, Campbell aims for cosmic terror, calling it “the highest aspiration of the field” because it results in “a sense of awe that can border on the numinous, or more precisely a dark version of that experience.”

The first novel in the series, The Searching Dead, introduces readers to 12-year-old Dominic Sheldrake, who is attending Holy Ghost Grammar. On top of the pitfalls of being the new kid at a strict Catholic institution, Dominic must also deal with the mysterious, dark nature of his history teacher, Christian Noble. Noble ultimately takes his history class, including Dominic and his best friend Jim, to the French battlefield where (as we later discover) Noble’s father had felt an evil presence during World War I. Also complicating Dominic’s school experience is his interest in writing dark fiction — specifically, the adventures of The Tremendous Three, a thinly veiled fictionalization of himself, Jim, and their best friend and mutual first love, Bobby (Roberta), as the trio battles monsters and other dark forces.

The novel’s action is set against the backdrop of 1950s Liverpool (Campbell’s birthplace) and that era’s popular culture, especially film. As Dominic begins to suspect that Noble is involved in pseudo-religious occult practices (which he disguises as Spiritualism), the boy is aided by Noble’s father, who manages to get into Dominic’s hands a secret journal that outlines Noble’s belief in the dark, supernatural underpinnings of the universe and hints at his plan to resurrect one of the old gods (which resembles Lovecraft’s Azathoth). As part of this plan, Noble uses flowers planted on gravesites to raise the spirits of his neighbors’ dead loved ones, in order to compel these spirits to do his bidding (which we find out later probably includes making contact with the entity). Even after Noble is fired from the school for his occult beliefs, he remains a threat, starting a church for Spiritualists that harbors a dark secret in its basement.

Born to the Dark follows Dominic into the 1980s, when he has become a married professor of film studies. His son Toby suffers from a mysterious condition that has begun to afflict many children: he has epileptic seizures that prevent him from sleeping well. Dominic and his wife Lesley locate a clinic called Safe to Sleep, which has gained a reputation for successfully treating these children. They enroll Toby and see instant results, but small clues begin to make Dominic believe that Noble, along with his daughter Christina (Tina, whom Dominic first met when she was a far-too-precocious and intelligent toddler), is behind both the clinic and the mysterious condition that has made its treatment program necessary in the first place. Moreover, he suspects that the treatment itself (akin to astral projection) is an ancient ritual that places the children in grave danger.

His investigation — aided by Bobby, who is now a journalist — reveals that the children, like the dead in the first novel, are being used as conduits to the dark gods. Manipulating the children allows Noble, Tina, and their son Christopher (Toph, revealed as a child of ritualistic incest in the third book) to safely contact the gods of chaos and usher their presence into the world. I must note here that Noble readily admits that the children are being used but claims it is for their own good as it prepares them for the inevitable destruction of the universe. Unfortunately, Dominic’s preoccupation with the Nobles comes to be seen as an obsession by his wife and the other parents of Safe to Sleep children; in fact, no one but Bobby and Jim, now a police officer, believes him. In addition, he discovers that the Nobles have friends in high places who can make his life miserable. Once again, a basement harbors a dark secret.

The Way of the Worm takes up three decades later, when an elderly Dominic once more encounters the Nobles (now living under their actual name, Le Bon, an anagram for Noble). The now-adult Toby Sheldrake and his wife, Claudine, who was also a Safe to Sleep child, along with their young daughter Macy, have joined the Church of the Eternal Three, which is headed by the Nobles/Le Bons. Because Toby and Claudine have been fully indoctrinated, they accept the ancient ritual that makes them conduits to the god of chaos, and they attempt to convince Dominic (now a widower) to join in the ritual so he too can be prepared. He agrees, but only because he sees an opportunity to spy on Noble and thwart his plan one last time. But Dominic soon discovers that he might be in over his head: not only are the rituals still being practiced, but the practice is also now international, and even more people in positions of authority are involved; as a result, he is compelled to tread lightly, both for his own sake and for the sake of Jim and Bobby, who have drawn the attention of the Nobles, the church’s leaders, and its cultish members (who harass them online).

As is usual for Campbell, the three novels, despite the obvious cosmic horror elements, are examples of the Gothic or dark fantasy genre. Campbell, a master of subtlety, never allows the trilogy’s monsters to take center stage for very long: they do appear, but are generally glimpsed briefly, or they make their presence known in the form of dream visions. Granted, this style of writing will not appeal to hardcore horror readers who crave high body counts and maximum splatter, but it will definitely appeal to fans of the macabre. For example, the “ghosts” in the first novel (which appear only briefly) are grotesque to the point of revulsion — they struggle to take human form and, in doing so, become nebulous, giant faces (almost filling a window), from which tendrils extend as they struggle to form arms and legs. Much like traditional folkloric ghosts, they whisper rather than talk, and they are cold and “squishy” to the touch. Needless to say, when Dominic encounters one (in book two), he is ill-equipped to deal with it, and it almost costs him his life. Also deeply macabre are the out-of-body encounters with the Lovecraftian entity, which takes the form of a giant dark mass of eyes and tendrils. These encounters are brief, as no human would be able to endure the entity’s presence for long, but they are disturbing. And the final meetings with the three serpentine Nobles, both at the instant of their supposed deaths and after they are transformed by death, convey a potent spookiness.

The trilogy’s other strength is its complexity. Readers are constantly kept off-balance by Noble’s claim that the destruction of the world is inevitable and that all he is doing is preparing willing human beings for the apocalypse. His position is bolstered by the fact that he never tries to stop Dominic by force, even though he has that power. Rather, he repeats his defense of embracing the inevitable, persistently inviting Dominic to become a member of his flock. While Dominic interprets numerous actions by Noble and his indoctrinated minions, especially those in positions of authority, as subtle threats, the novels also offer ample evidence that he has an overly active imagination, so it is left up to the reader to determine the extent of Dominic’s (un)reliability. Campbell sustains the tension between these possible readings of Noble’s motivations and Dominic’s reactions throughout the trilogy, holding until its very end the scenes that make clear there may indeed be evil forces at work.

Part of this narrative complexity is due to the role of Dominic himself. As it turns out, the Nobles are in need of a “useful idiot” who will unwittingly set some of the wheels in motion that usher in the end of the human reign on Earth. Considering that the holy trinity, according to the Nobles’ religion, is Past, Present, and Future, and considering that part of their astral projection ritual allows a person to see all of time at once, even beyond the date of his or her demise, it stands to reason that the Nobles know they need Dominic to take the actions he takes, up to and including simply being late to catch a train. This setup puts me in mind of the end credits to the 1992 horror film masterpiece, Candyman, wherein subtle hints in wall murals change the narrative completely: as it turns out, the eponymous revenging revenant needed a human being to “kill” him so that he could transform (and could gain a ghostly convert), and we know this because the murals, which are in his unique style, depict events that occurred after his supposed death. As it turns out, in The Way of the Worm, seemingly inconsequential actions Dominic had undertaken in The Searching Dead and Born to the Dark, along with his inability to comprehend the power of religion (especially that of a cult), plays into the Nobles’ plans, despite his apparent small successes at thwarting them. One could even say that the tragic ending of the trilogy could not have happened without Dominic’s attempts to stop it.

And that brings me to what I like the most about this trilogy: Campbell’s understanding that horror, to be masterful, requires sadness and grief. After all, if the purpose of a story is to introduce a serious, likely unstoppable threat to human life, then some of the characters are going to die. I won’t offer spoilers here, but I will say that Campbell allows the story to go where it logically needs to go, and that means tragic (and in some cases horrific, even if “offscreen”) deaths for characters whom readers have learned to care about. Fortunately, Campbell eschews the “heroic sacrifice” convention and the even more annoying plot cliché where the monster is defeated with love and/or friendship and/or positive thoughts. Granted, what this leaves is a grim and tragic vision, with some character deaths seeming almost senseless. What will stick with readers after finishing this trilogy is the fact that none of the deaths were actually necessary in the grand scheme of the cosmic entity or the Nobles. They happened because, well, death is what could occur when a person opens the door to something dark and sinister, even accidentally. Ultimately, the vision of the trilogy is as dark and existential as Dominic’s lapsed-Catholic-turned-agnostic worldview. The story ends, but the threat is still out there (another annoying convention Campbell avoids is the destruction of the unkillable monster), and readers have only a glimpse of how bad it might be.

All that being said, these novels — while offering more examples of Campbell’s brilliant wordsmithery — do not rank, in my opinion, with his better works, for the simple reason that Campbell’s style of horror — holding off the monster until the very end, giving only brief glimpses of the grotesque along the way, sowing doubt that seemingly supernatural events may be merely the product of an overactive imagination — does not lend itself to a trilogy’s length. In fact, the three novels come across structurally as a prison of the author’s own making, one in which he seems to have wanted to parade out the monster but could not bring himself to do so. I kept getting the impression of being set up with pulled punches. For example, The Searching Dead includes some wonderfully eerie scenes wherein 12-year-old Dominic thinks he hears or sees something dreadful, only to dismiss the occurrence as imaginary; in two instances, downright terrifying scenes turn out to be (I almost hate to say it) merely dreams. While readers can endure this coy withholding of the central horror for the length of a short story (à la M. R. James) or a masterfully written novel (such as Campbell’s own The House on Nazareth Hill), they are likely to get a bit perturbed when the horror is just a series of red herrings for three consecutive books. In fact, I held off reviewing The Searching Dead and Born to the Dark precisely because I was hoping that the horror would make itself more known (and therefore more disquieting) in The Way of the Worm.

This is not to say that I wouldn’t recommend the trilogy for Campbell fans (after all, they know what to expect) or for fans of Lovecraft (there is just about enough cosmic horror here to keep them entertained). However, I think fans expecting a sustained cascade of scares will be disappointed. In fact, the real fan base for this trilogy may be readers who do not usually pick up horror novels. As I was making my way through the trilogy, I couldn’t help but wonder why Campbell has never attempted mainstream fiction, and then I realized that, in many ways, he had done so before and was again. He has, after all, written novels about the pressures of being a single parent (albeit with a haunted boardinghouse as a backdrop) and of watching a loved one die (although she may have never been real to begin with), two thematic concerns of many mainstream novels. He has even written a novel about being wrongly accused of a crime (but one full of disembodied voices and a helpful ghost). One could argue that this new trilogy holds a potential appeal for mainstream readers, given many of its core concerns: being the new kid in school, having your work dismissed, having your heart broken, enduring separation and near divorce, losing your wife, losing your friends, and helplessly watching your child and grandchild drift away. To put it another way, mainstream readers will find plenty to identify with in these three novels, as they would if they picked up many of Campbell’s earlier works.

¤

Tony Fonseca is the author of numerous books and articles on horror fiction.

LARB Contributor

Anthony J. (Tony) Fonseca is the library director of Alumnae Library, Elms College, Massachusetts. He is the co-author of three books on horror — Encyclopedia of the Zombie: The Walking Dead in Popular Culture, Ghosts in Popular Culture and Legend: An Encyclopedia, and Richard Matheson’s Monsters: Gender in the Stories, Scripts, Novels, and Twilight Zone Episodes — and has published chapters in Dracula’s Daughters: The Female Vampire on Film (edited by Douglas Brode and Leah Deyneka) and Ramsey Campbell: Critical Essays on the Modern Master of Horror (edited by Gary William Crawford). He has also co-authored books on music and librarianship: Hip Hop Around the World: An Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia of Musicians and Bands on Film, and Proactive Marketing for the New and Experienced Library Director. His book Listen to Rap!: Exploring a Musical Genre will be out in September. He has previously published chapters/articles on weird-fiction author Robert Aickman, doppelgängers, psychics, horror readership, vampire music, bhangra-beat music, patron-driven acquisitions, and information literacy trends in academia. His current non-scholarly projects include being co-owner of Dapper Kitty Music and Gothic and Main Publishing.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Grim Hints and Nervous Portents: On Dennis Etchison

The late horror author’s vivid snapshots of bleak Southern California suburbia.

The Wide, Forbidding Cosmos: The Weird Fiction of John Langan

John Langan’s latest collection of weird fiction is a fresh waypoint, if not a landmark, in his creative journey.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!