History’s Final Verdict on Vichy France? On Julian Jackson’s “France on Trial”

John Reeves considers Julian Jackson’s “France on Trial: The Case of Marshal Pétain.”

By John ReevesNovember 12, 2023

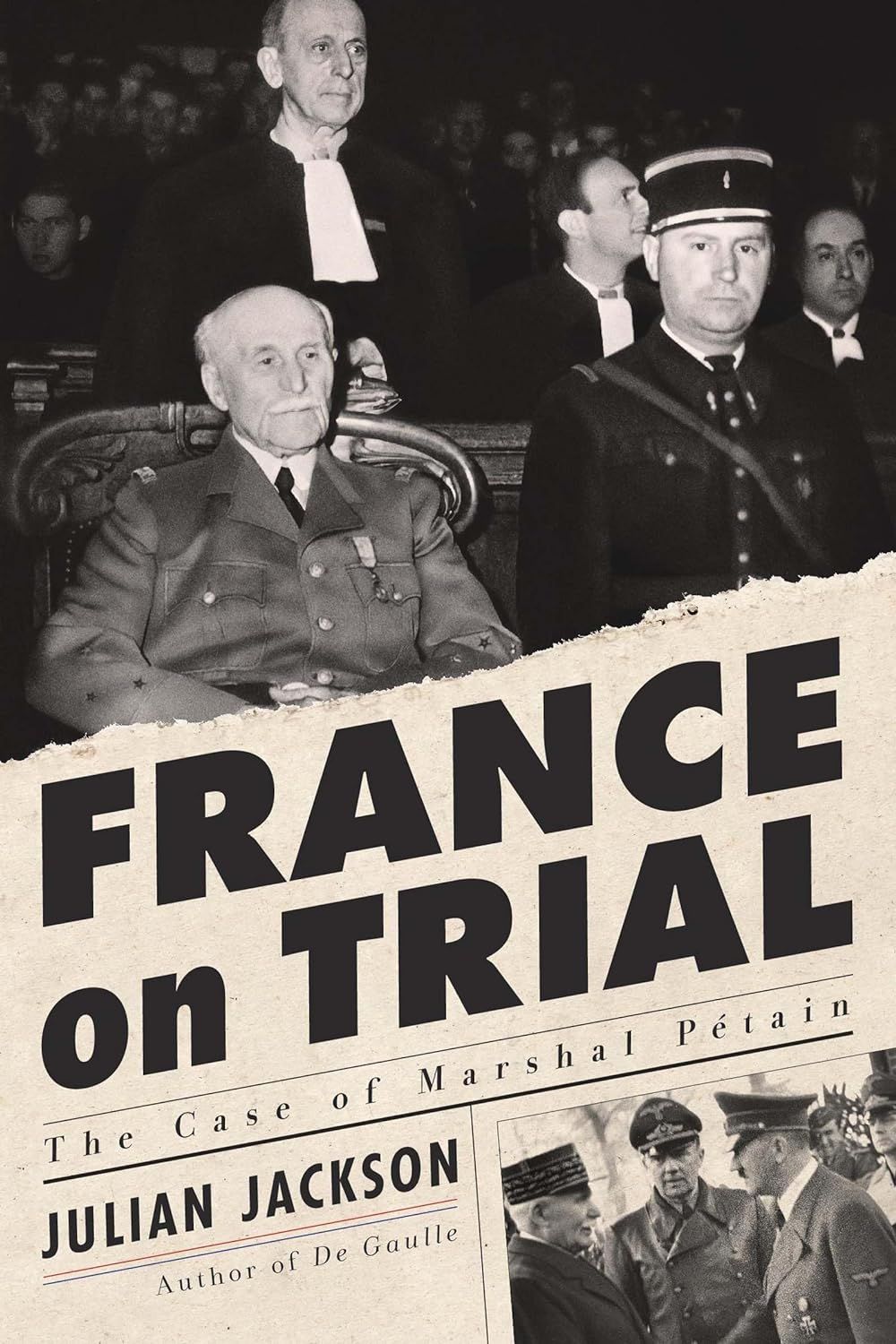

France on Trial: The Case of Marshal Pétain by Julian Jackson. Belknap Press. 480 pages.

TESTIFYING AT the trial of Nazi collaborator Marshal Philippe Pétain in 1945, the French politician Léon Blum said that the greatest blow to the people was the expenditure of trust.

Pétain was a genuine national hero, the triumphant general of the World War I stand at Verdun, who told his countrymen in 1940 that an armistice with Hitler’s Germany would be in the best interests of the nation and would not be dishonorable.

“And this population,” Blum said solemnly, “believed what it had been told because the man who had uttered these words spoke with the authority of his great military past, in the name of glory and victory, in the name of the army, in the name of honour.” He continued, “So that for me is the key issue: the massive and atrocious abuse of moral confidence. Yes, I think that can be called treason.”

Of this testimony, a French journalist wrote, “Blum’s quavering voice suddenly transplanted us back into the moment which remains for us a wound that has not healed. One had to witness Blum’s tears to feel so vividly all that we have suffered.”

A French jury convicted the 89-year-old Pétain of treason and condemned him to the death penalty. Due to his advanced age, the sentence was commuted to life in prison. This landmark event—billed as “the greatest trial in history”—is the subject of the exceptional new book France on Trial: The Case of Marshal Pétain, by award-winning author Julian Jackson. A highly detailed account of the trial itself is presented in the first two parts of the book, while the concluding section offers a painful examination of the Vichy regime’s role in the Holocaust.

“Revisiting Pétain’s trial,” Jackson writes, “is not the same as re-opening it. It offers a fascinating opportunity to watch the French debating their history.” Their grasp of Vichy history was much different in 1945 from how it would become in subsequent decades.

Born in 1856, Pétain had been a colonel at the outbreak of World War I in 1914, before being promoted to army commander after just 18 months. An excellent tactician, he provided calm, inspirational leadership to panicked French soldiers at Verdun shortly after the initial German attack in late February 1916. “His mythic stature,” Jackson writes, “was also sustained by his appearance: piercing blue eyes, snow-white hair, and his famous ‘marble countenance’ (visage marmoréen).”

During the 1930s, Pétain viewed communism as France’s greatest threat and found himself increasingly attracted to authoritarian regimes. In 1940, he blamed French politicians for dragging France into war with Hitler, telling the French people, “I hate the lies that have done you so much harm.” Pétain defended collaboration with Nazi Germany as essential to protecting French citizens. His political rival Charles de Gaulle felt Pétain “was a great man who was destroyed by ambition,” adding that “he did not take power in 1940 with very commendable intentions.” American journalist William Shirer wrote that, during the Vichy years, Pétain “became, like Hitler, the law itself, imprisoning men, especially the leaders of the Third Republic without trial.”

Astonishingly, the Vichy government’s treatment of Jews was not a primary factor in the verdict. “This fact,” Jackson writes, “came to seem incomprehensible following a major shift in public perceptions about the importance of the Holocaust.” During the trial, we learn, more court attention was spent on a single document relating to the Allied landing at Dieppe in August 1942 “than to the fact that in the month it was sent—or not sent—over 11,000 Jewish men, women and children were arrested by French police in the Unoccupied Zone of France for deportation to Auschwitz.”

In the months before the trial, public attitudes toward Pétain had begun to change. In September 1944, only three percent of the French believed that he deserved the death penalty. By May 1945, after the war in Europe had ended, that figure was 44 percent. But the prosecution of Pétain proved to be more difficult than expected. All along, he maintained that he had been forced to do an unpleasant but necessary job, declaring in 1944, “[I]f I could no longer be your sword, I have wanted to be your shield.” His talented defense attorney, Jacques Isorni, believed, according to Jackson, that “Pétain still maintained an emotional hold on the French […] that if he was guilty, so was all of France.” Jackson, who has an impressive command of the nuances of this trial, implies that Isorni was perhaps the most effective of all the lawyers on both sides of the case.

The prosecution unconvincingly suggested that Pétain had been involved in a prewar plot against the French government. But they presented damning testimony that Pétain had supported the efforts of a paramilitary group that fought against the Resistance. “Patiently, stitch by stitch,” wrote an observer of the lead prosecutor’s closing remarks, “he weaves the net which encircles, snares and then suffocates the accused.” Pétain’s reliance on the odious Vichy politician Pierre Laval—who would eventually be tried, convicted, and executed for his crimes later in 1945—didn’t help his case. Laval, who said in 1942, “I wish for the victory of Germany,” later told the court, “I briefed [Pétain] fully, as far as I could, I took account of his opinions … Of course the Marshal was au courant.” At a meeting in July 1942, Laval referred to foreign Jews in France as “garbage waste [déchets] sent by the Germans.”

No Holocaust victims were invited to testify. The true magnitude of Vichy’s atrocities would not become apparent for many years afterward. Jackson invokes the work of historian Robert Paxton, who showed in 1972 “that the first repressive policies of the Vichy regime, including the persecution of the Jews, were entirely home-grown and not the result of German pressure.” For the entire war, 74,182 Jews living in France died in the Holocaust with Auschwitz being the destination for approximately 70,000 of them. Almost 2,000 of the victims were under six years old. Only 2,564 Jews who were deported survived.

Toward the end of this authoritative book, Jackson presents an unsparing indictment: “According to the most unfavourable interpretation, Vichy aided the German arrests in 1942 because it saw an opportunity to rid France of foreign Jews who were widely seen as an encumbrance.” A “slightly less unfavourable interpretation,” he continues, is that Vichy “aided the Germans because, for a regime saturated with anti-semitic prejudices, saving Jews was less of a priority than maintaining the illusion of sovereignty through the policy of collaboration. That was Vichy’s crime.”

Jackson concludes by declaring: “The Pétain case is closed.” He takes as evidence the April 2022 defeat of French presidential candidate Éric Zemmour, a prominent defender of the Vichy regime. Jackson may be right about the legacy of Pétain in particular, though the popular appeal of authoritarian leaders like him continues to be a threat to Western democracies. Shortly after France’s defeat in 1940, the American ambassador in France recounted Pétain suggesting that “it would be a good thing for France if the parliamentarians who had been responsible not only for the policies which had led to the war but also for the relative unpreparedness of France should be eliminated from the French government.” Pétain’s belief that democratic institutions were unable to solve the most challenging problems of war and peace remains pervasive today.

¤

John Reeves is the author of Soldier of Destiny: Slavery, Secession, and the Redemption of Ulysses S. Grant (2023) and A Fire in the Wilderness: The First Battle Between Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee (2021). You can learn more about him at john-reeves.com.

LARB Contributor

John Reeves is the author of Soldier of Destiny: Slavery, Secession, and the Redemption of Ulysses S. Grant (2023) and A Fire in the Wilderness: The First Battle Between Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee (2021). He has taught European and American history at Lehman College, Bronx Community College, and London South Bank University. He lives in Washington, DC. You can learn more about him at john-reeves.com.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“The Leprosy of the Soul in Our Time”: On the European Origins of the “Great Replacement” Theory

Richard Wolin excavates the roots of the right-wing conspiracy theory that liberal elites are trying to “replace” white Americans with nonwhites.

French Secularism, Reinvented

What can France’s history with Catholicism tell us about today’s culture wars over Islam?

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!